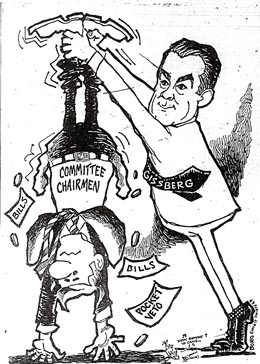

William Gissberg was a powerful Democratic senator in the Washington State Senate between 1953 and 1973. Blunt, outspoken, a hard-charging man, many of his contemporaries considered him to be among the leading members of the Senate (at one point he served on 11 committees at one time) during his two decades in office. He had a talent for being able to quickly read and dissect proposed legislation and identify the relevant issues and arguments both pro and con, which earned him the respect of friend and foe alike. He is especially remembered for his work on environmental issues, particularly Washington state's Shoreline Management Act.

Early Years

William Albert Gissberg was born in Everett (Snohomish County) on September 17, 1922, the son of Helmer Albert Gissberg (1890-1960) and Esther Lindstrom (b. ca. 1894). Gissberg’s parents were both Swedish immigrants. They married in Bellingham in 1914, but at some point (probably later in the 1910s) relocated to Everett. They had three children: Vera, Gus, and William; William was known variously as “Bill” and “Giss.”

Gissberg grew up in Everett. His parents divorced when he was young and he lived with his mother. He developed an aptitude for sports at an early age, and particularly enjoyed baseball. But it was his success on the basketball court that brought him statewide recognition during his senior year in high school. He was part of the undefeated 1940 Everett High School basketball team, known as the “wonder team,” which won the state championship and is still regarded as one of the best teams in state history.

He attended a year of college at the University of Oregon before transferring to the University of Washington. After the United States entered World War II in 1941 he continued his studies under the V-12 program (intending to go to officer training school for the Marines), and started law school. But he then joined the Navy, where he rose to the rank of lieutenant and served in the Pacific theater on the ship USS Casa Grande. He participated in the invasions of the Leyte and Lingayen gulfs in the Philippines and the invasion of Okinawa during the final year of the war.

After the war ended in 1945 Gissberg returned to Washington state, and in 1946 resumed his studies at the University of Washington Law School, also finding time to play baseball on the college’s baseball team. He graduated in 1948, passed the bar exam, and was admitted to the Washington State Bar in 1949. He briefly considered returning to Oregon to practice law, but instead opted to remain in Washington and opened his first office in Marysville in April 1949. He later formed a partnership with a law firm in Everett which became known as McCrea, Kafer, Gissberg, and Wilson.

State Senator

In November 1952 Gissberg, a Democrat, was elected state senator for the 39th Legislative District, a mostly rural Snohomish County district that included Arlington and Monroe (and also, until the 1960s, a part of Island County). When he was interviewed in the mid-1990s as part of the Washington State Oral History Program, he explained that his decision to become a Democrat stemmed from seeing how programs passed by the Democrats in the 1930s to counter the economic ravages of the Great Depression helped the country in general and his brother and mother in particular survive the effects of the Depression.

Gissberg’s term in Olympia began in January 1953. He later said that when he joined the Legislature it was customary for freshmen legislators to be seen and not heard. But that wasn’t his style. Blunt and outspoken, not known as a patient man, and not afraid to go his own way (a Senate colleague, Martin Durkan [1923-2005], later described Gissberg as a “‘oner’ among loners”), he was soon piping up during legislative sessions. On one particular occasion during his first term he made a motion on the Senate floor to relieve the Rules Committee of further consideration of a bill involving unemployment compensation, drawing the ire of a more senior senator, Victor Zednick, who took the floor to argue against Gissberg’s motion; for good measure, he called Gissberg a “whippersnapper.”

But Gissberg was not deterred. In his second legislative session (1955) he introduced 34 bills, and 19 of them passed the Senate and were signed by Governor Arthur Langlie (1900-1966). A 1955 Marysville Globe article pointed out this “batting average” (a nod to Gissberg’s baseball prowess in his college years, when he played for the UW) was .538 (it actually equated to .559), and noted this was one of the highest among members of both legislative houses. Some of the legislation Gissberg introduced in 1955 included a veterans’ bonus bill for veterans of the recently ended Korean War, a bill increasing weekly unemployment compensation benefits, and, in a harbinger of the active role he would later play in environmental legislation, a bill to increase the appropriation from $5,000 to $30,000 for the development of Mt. Pilchuck State Park.

Eleven Committees

Gissberg flourished in the Senate. He later recalled that at one point he served on as many as 11 committees at one time, including the Judiciary Committee, the Rules Committee, the Education Committee, and later the Natural Resources Committee. But he never lost sight of his constituency. He later explained that he understood he was elected to represent the voters in his district, and voted the way he believed they wanted him to vote on the issues that came before him, even if he personally disagreed with their position. One such example involved efforts to liberalize liquor laws. Gissberg readily admitted to enjoying a cocktail after the workday ended, but in his interview said he always voted against liberalizing liquor laws because he knew that the majority of voters in his district did not support it.

Late in 1960 Gissberg ran for majority leader of the Senate against Robert “Bob” Greive (1919-2004), losing by either one or two votes (accounts differ). In his oral history, Gissberg told an amusing story of the vote:

"I specifically asked him [Governor Albert Rosellini] to contact two of the senators from Spokane whose names I won’t mention. Al contacted them and reported back to me that he had received assurance from both of them that they’d vote for me ... . The first fellow who voted, voted for Greive ... . The other senator from Spokane was voting and I glanced across the table which was about three feet across and could plainly see that he put down ‘B.G,’ the initials, ‘B.G.’ I objected right away. I said ‘You can’t leave your ballot like that. No one’s going to know who you voted for.’ He said ‘Well, I voted for you’ and left it ‘B.G.’ Well, of course, it was the funniest thing that ever happened. They threw his vote out” (Gissberg, 24).

Years later fellow senator Martin Durkan added a codicil to the story:

“Later I asked him [Gissberg] why he thought those two senators did not support him. His response: ‘I didn’t want to owe them anything, so I didn’t ask them’” (Gissberg, foreword).

On March 24, 1962, Gissberg married Helen Rich of Bothell (it was his second marriage; his first, to Swedin Solvig in 1946, had ended some time earlier). But 1962 was also a significant year for Gissberg for another reason: He was groomed by state Democrats to run for Congress. He went to Washington, D.C., to look into it, but while he was there he also took a look at the Potomac River. He explained more than 30 years later:

“I walked to the Potomac River, and looked into that river, and saw a sea of mud running in the Potomac River, and I suddenly faced realistically what I was doing. I give up my home in the Northwest to go to Washington, D.C. and the turmoil that exists there, and I thought to myself, ‘There’s no steelhead [trout] in that Potomac River’ so I decided then and there I wasn’t going to do it” (Gissberg, 19).

Gissberg and the Environment

Gissberg was elected president pro tem of the Senate in 1965 and served in that position until 1967, but his later years in the Senate were particularly focused on environmental legislation. He had always been interested in the environment -- he loved the outdoors, especially fishing and camping -- and even as early as the mid-1950s introduced legislation to create a statewide air pollution control authority. (It was countered by Republicans in the Senate, who instead passed legislation that created local pollution control authorities. The state Department of Ecology later gained control of the local pollution control authorities when it was formed in 1971 -- and Gissberg was involved in drafting the rules and regulations that formed the Department of Ecology.)

As chairman of the ad hoc subcommittee of the Senate Natural Resources Committee, Gissberg played an active role in working out various provisions of the Shoreline Management Act to ensure its passage in the Legislature in 1971. Approved by state voters in 1972, the Shoreline Management Act provides for the management of development along the state’s shorelines. Local governments administer and issue shoreline usage permits, which are then reviewed and approved (or declined) by the Department of Ecology. The Shoreline Management Act also created the Shorelines Hearings Board, which hears appeals from these permit decisions (as well as appeals of shoreline penalties issued for violations of the act) and Gissberg served on this board later in the 1970s.

Gissberg commented in his interview that he was especially proud of an amendment he made to a bill (perhaps the Shoreline Management Act, but he didn’t specify which bill) that prohibited the sale of shorelines and tidelands by the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), explaining that he felt the DNR was divesting the public of the ability to use these areas. For though he was an ardent environmentalist, he was also practical. He felt that some of the environmentalists of the 1960s and 1970s went too far by attempting to limit development to the point that it was unrealistic to comply with, and sought to curb what he viewed as these excesses. He maintained this philosophy throughout the rest of his career.

Gissberg decided not to seek re-election in 1972. He later explained why:

“I loved serving in the Senate for the first ten years. It was everything I expected it to be. Honorable. People weren’t possessed of burning political ambitions to be ahead. You could believe what everyone told you ... . [But by 1972] I was tired of the Legislature; the sessions became so long and burdensome, and my law partners became disenchanted with my being gone” (Gissberg, 19, 60).

Later Years

Gissberg’s final term ended in January 1973, but Governor Dan Evans (b. 1925) then appointed him to the Pollution Control Hearings Board, prompting the Gissberg family to move to Olympia. He served on the board until 1978, also serving during this time as chairman of the Council on Environmental Policy for about two years, as well as on the Shorelines Hearing Board.

He briefly found himself unemployed when his term on the Pollution Control Hearings Board expired in 1978. He wasn’t interested in going back to a law practice, but soon learned that the Washington State Bar Association (WSBA) was looking for a lobbyist. He was hired and served full-time for a year, and is especially remembered for his advice on behalf of the WSBA to the Senate in the 1979 legislative session, which helped defeat a products liability bill that sought to limit remedies to those injured by defective products. Later in 1979 he retired as a full-time lobbyist but continued to work part-time until 1984, mainly reviewing legislative bills; he had a well-earned reputation for being able to review a proposed bill and quickly identify and analyze the salient points in the bill.

Gissberg’s final years were quieter. In the early 1990s he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. He died on December 30, 2002, in Marysville. He was survived by his wife, Helen, and six children: sons Terry and Thomas, and daughters Erica, Kris, Sonja, and Stefani. In a nod to his efforts to protect the environment, Gissberg Twin Lakes County Park north of Marysville is named after him.

At the end of his interview for the Washington State Oral History Program, the interviewer asked Gissberg what he would say to someone considering public service. His answer: “I’d encourage them by saying you can make a difference. If they believe they can make a difference, they can make a difference” (Gissberg, 90).