On Sunday night, March 19, 1950, 18-year-old Jo Ann Dewey (1931-1950) is abducted by two men in Vancouver, Washington, while walking from the Central Bus Depot one-half mile to Saint Joseph Hospital and Nursing School. Several of witnesses see her struggling with her abductors and hear her screams for help, but no one interferes. A week later, three fishermen find Dewey’s nude body lodged among the boulders on a gravel bar in the Wind River in Skamania County. The clues point to two brothers from Camas, Turman Galilee Wilson (1926-1953) and Utah Eugene Wilson (1930-1953), both ex-convicts with histories of violence. On March 30, 1950, the two fugitives are captured in Sacramento, California, returned to Vancouver and charged with kidnapping and murder. In June 1950, the Wilsons will be convicted of the kidnapping and first-degree murder of Jo Ann Dewey in Clark County Superior Court and sentenced to death. After the appeal process has run its course, the brothers will be hanged together at the Washington State Penitentiary on January 3, 1953. It will be the second double execution in state history and the first time that two brothers have died together on the gallows.

Screams Disregarded

Jo Ann Dewey worked in the kitchen at the Portland Adventist Sanitarium, (now the Marquis Care Center) 60th Avenue SE and SE Belmont Street in the Mount Tabor neighborhood. At 10:25 p.m., Sunday, March 19, 1950, she purchased a ticket at the downtown bus depot in Portland, Oregon, to go to Vancouver, Washington. At about 11:15 p.m., she telephoned her mother, Mrs. Anna Elizabeth Dewey, from the Central Bus Depot, 415 Main Street, Vancouver, concerning a ride to her parents home in Battle Ground. She told Jo Ann to come home with a neighbor who worked at St. Joseph Hospital and Nursing School, E 12th and E Reserve Streets. The hospital was only half-a-mile from the downtown bus depot, an easy 10 minute walk. But Jo Ann Dewey never reached the hospital.

At about 11:30 p.m., a woman’s terrified screams were heard by residents in the Central Court Apartments, E 12th and D streets, and students at St. Joseph Nursing School, two blocks away. Witnesses said they saw a young woman struggling with two men under a dim streetlight, but no one interfered. One witnesses, veterinarian Dr. Chester N. Thackeray, came out of his apartment and, from a safe distance, complained about the disturbance. “Shut up, this is my wife,” one man replied. “No, I’m not, I’m not,” the woman screamed (The Walla Walla Union-Bulletin).

The men punched the young woman in the head and face, dragged her into an older-model black Buick sedan, and drove away with its lights off before witnesses could summon police assistance or obtain the car’s license number. The Vancouver Police Department, however, was notified of the disturbance and sent two patrol officers, Carl Forsbeck and Frank Irwin, to investigate. In the street near where the sedan had been standing, they found a strap torn from a woman’s handbag, a barrette and a partially empty bottle of Rainier Beer laying in the street. The items were dutifully collected as evidence of a potential crime.

The Search Begins

But the fact the incident had been an abduction rather than a family dispute wasn’t discovered until the following day. On Monday afternoon, March 20, 1950, Anna E. Dewey telephoned the Vancouver Police Department to report her daughter, Jo Ann, was missing. She was supposed to meet a friend at St. Joseph Hospital for a ride home, but failed to show up and hadn’t been heard from.

Vancouver Police Chief Harry Diamond assembled teams of officers and hundreds of volunteers to search parks, ravines, lake shores, river banks, and other isolated areas in and around the city. Clark County Sheriff Earl N. Anderson assigned deputies to roam the back roads and inspect all deserted buildings, and sent search parties into remote woodland areas. On Thursday, authorities conceded the search for clues to Dewey’s disappearance had been fruitless, and asked citizens to report anything that appeared suspicious.

Jo Ann Is Found

On Sunday morning, March 26, 1950, three salmon fishermen, Robert Rummel and Gerald Frandle of Yakima and Ray Lowrey of Tieton, found the nude body of a young woman lodged among the boulders on a gravel bar in the Wind River in Skamania County. The location, approximately 44 miles east of Vancouver and one mile north of Carson, was two miles below a narrow 28-foot high suspension bridge across the river. A state-wide alert had been issued for Jo Ann Dewey and the body was soon identified as the victim. A search of the area by the Skamania County Sheriff’s Department, however, failed to turn up either her personal effects or clothing.

A preliminary report from Clark County Corner Roy Spady indicated Dewey had been dead about a week and death was probably caused by a severe cerebral hemorrhage. But at the coroner’s inquest, held the following day, Dr. Howard L. Richardson, the chief pathologist from the Oregon State Police crime laboratory, testified that the postmortem revealed that she died from carbon monoxide poisoning. Dewey had been severely beaten and sexually assaulted and then apparently stuffed into the trunk of an automobile with a defective exhaust system. Two serious head wounds, inflicted before death, indicated the victim may have been knocked unconscious. After finding her dead, the kidnappers disposed of her personal effects and clothing, drove to the remote Wind River canyon and threw her body off a footbridge. The multitude of lacerations and contusions on the body were caused by rocks and debris as it washed down the fast-running river.

On Wednesday, March 29, 1950, more than 800 people attended Jo Ann Dewey’s funeral service, held at the Seventh Day Adventist Church in Meadow Glade. She was buried in Brush Prairie Cemetery, NE 117th Avenue and NE 113th Circle, Brush Prairie.

The Suspects

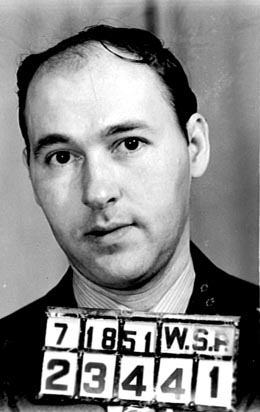

The investigation soon focused on two brothers, Turman Galilee Wilson, age 24, and Utah Eugene Wilson, age 20, who lived with their mother, Eunice E. Wilson, at Fern Prairie, five miles north of Camas. Both brothers had extensive police records which included crimes of violence. Fingerprints found on the beer bottle recovered at the scene of the abduction belonged to Utah Wilson. In 1946, he had been sent to Green Hill School in Chehalis for burglary and assault. In 1948, he pleaded guilty to two counts of burglary in Clark County Superior Court and was sentenced to one year in the county jail and two years probation.

The case reminded Portland detectives of an abduction and rape of a 17-year-old girl in 1942 which sent three Wilson brothers, Turman, Rassie, and Glenn, to the Oregon State Penitentiary. Turman had been released on parole in 1948, but the other two were still serving 20-year sentences. That same year, Turman was arrested for robbery in Portland. He pleaded guilty to the reduced charge of petty larceny and was sentenced to six months in jail. He had also been arrested for a variety of other crimes ranging from vagrancy to assault with a deadly weapon, but the charges had all been dismissed. Police had been looking to question Turman and Utah for several days, but the two men had dropped out of sight.

As for their parents, Moses R. Wilson had served seven years in Washington State Penitentiary for the molestation of a 13-year-old girl in 1933. His FBI rap sheet had a series of arrests for theft, drunk and disorderly conduct, and disturbing the peace. In December 1949, Moses was sentenced to 90 days in the Clark County jail for drunk and disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. Estranged from his wife, Eunice, he was living in a trailer house near Silverton, Oregon. Eunice Wilson received a 10-year suspended sentence for harboring a fugitive when son Glenn escaped from prison in 1946 and was found hiding at the Wilson home in Fern Prairie, disguised as a woman.

Fleeing and Pursuing

On Thursday, March 30, Clark County Prosecutor R. DeWitt Jones (1909-1993) filed an information in superior court charging the Wilsons with kidnapping and first-degree murder. Based on this filing, U.S. Attorney Harry Sager filed a complaint with U.S. Commissioner DeWitt C. Rowland in Tacoma, charging the Wilsons with unlawful flight to avoid prosecution, a violation of the Fugitive Felon Act, and federal warrants were issued for their arrest.

The Fugitive Felon Act (18 USC 1073) was primarily enacted to permit the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) or other federal investigative agencies to assist states in the location and apprehension of fugitives. The federal complaint for unlawful flight to avoid prosecution is usually dismissed once the fugitive is apprehended and turned over to state authorities to await interstate extradition.

During the investigation, police recovered two automobiles connected with the Wilson brothers, a cream-colored Pontiac sedan abandoned in Portland, Oregon, and a black Buick sedan found in Camas, Washington. Both were registered to Grant I. Wilson, the youngest brother, who lived in Camas with his wife, Hazel. Grant had left his wretched home life at age 16 and was the only one of the five Wilson brothers, still living, who had never been connected with any crime. When questioned, Grant, upon the advice of his pastor at the Assembly of God Church, told Vancouver Police Detectives Floyd W. Borgen and Julian A. Ulmer that Turman and Utah left his house on Monday, March 27, saying they were going to Silverton, Oregon, to visit their father. They were driving a used Oldsmobile that Turman, using the alias Ted E. Davis, had purchased in Portland on March 22. On Wednesday, March 29, however, Turman called from a motel in Sacramento, California, asking if Grant had inquiries from the police.

The FBI immediately notified their Sacramento Field Office which requested the Sacramento Police Department to be on the lookout for the Oldsmobile. At 4:15 p.m., March 30, a police cruiser spotted the vehicle parked four blocks from the Governor’s mansion, and city detectives and FBI agents staked it out. At 6:55 p.m., the Wilson brothers returned to the car and were arrested without a struggle. Utah was carrying a Llama .25-caliber semiautomatic pistol and a.38-caliber, six-shot revolver was found under the front seat of the automobile. The brothers had registered in a Sacramento motel under fictitious names and had only revealed their true identity after being arrested. Utah was in possession of $550 in $10 bills which he claimed he had stolen in a series of burglaries for which he had spent one year in Clark County Jail. “The money belongs to me because I earned it doing time in prison,” Utah told agents (The Seattle Times).

On Friday, April 1, the Wilson brothers appeared before U.S. Commissioner Adellia S. McCabe in Sacramento and charged with unlawful flight to avoid prosecution. Bail was set at $25,000 each, which they could not post. Vancouver Detectives Borgen and Ulmer flew to Sacramento with copies of the arrest warrants issued by Clark County to begin removal proceedings, but the defendants waived extradition. Early Saturday morning, Chief Harry Diamond, Sheriff Earl Anderson and two deputies left Vancouver in two automobiles to bring the fugitives back to Washington state for trial.

The Trial

On Thursday, April 20, 1950, Turman and Utah Wilson appeared before Clark County Superior Court Judge Charles W. Hall for arraignment. The defendants pleaded not guilty to the charges of kidnapping and first-degree murder and were ordered held without bail. Attorneys Irvin Goodman of Portland and Sandford Clement of Vancouver were appointed defense counsel and trial was scheduled to commence on June 12, 1950, before Judge Eugene C. Cushing Jr.

Trial began on Monday morning, June 12, 1950, with jury selection, which took two-and-a-half days to complete. The questioning of prospective jurors centered on their views about the death penalty. On Wednesday afternoon a jury of four women and eight men, plus two alternates, was impaneled and sworn in. After the noon recess, the jury was taken to the street where Jo Ann Dewey was abducted.

At 3:00 p.m. Prosecuting Attorney Jones presented his opening statement in which he outlined the state’s case against the defendants. Turman and Utah Wilson, both convicted felons, kidnapped Jo Ann Dewey intending to rape her. She was severely beaten and sexually assaulted and then stuffed into the trunk of an automobile with a defective exhaust system. She died within an hour of abduction from carbon monoxide poisoning. After disposing of the body in the remote Wind River canyon in Skamania County, the defendants went into hiding to avoid police questioning and then fled to California after Dewey’s body was found. A beer bottle bearing Utah’s fingerprints, found in the street shortly after the abduction, put the brothers at the crime scene.

In his opening statement, Defense Attorney Irvin Goodman portrayed the Wilson brothers as callow youths who went astray, but were trying to go straight, only to find they were hounded by police at every turn. Utah Wilson, who was on parole for burglary, believed police suspected him of stealing a power saw. Fearing his parole would be revoked, he went into hiding on Saturday, the day before Jo Ann Dewey was kidnapped. Thurman Wilson, who was also on parole, quit his job at Pendleton Woolen Mills in Washougal to accompany his brother so that he would not be alone. The Wilsons roamed the Vancouver-Portland area for several days after the abduction, changing cars and evading police, then drifted to Silverton, Oregon, and finally to Sacramento, California, where they were apprehended. At the time of the abduction on March 19, the defendants were at the Playhouse Theater, 1107 SW Morrison Street, in downtown Portland watching a double-bill movie. After the theater let out, they had car trouble and didn’t return to Vancouver until 2:00 a.m., March 20.

The state rested its case late Tuesday afternoon, June 20, 1950, after five days of direct testimony from 34 witnesses. Defense Attorney Goodman then moved for dismissal of the case against the Wilsons on the grounds of insufficient evidence and prosecutorial misconduct, which Judge Cushing denied.

The Wilsons' main defense was to show an convincing alibi. Attorney Goodman attempted to present testimony from four usherettes at the Playhouse Theater that the defendants were there watching a movie on the night of March 19, 1950. Unfortunately, the witnesses were not able to remember times and dates clearly enough to substantiate the alibi. One witness testified she positively remembered seeing the brothers enter the theater at approximately 8:30 p.m., however, the manager's work records revealed she had not worked that night. Even if the defendants were at the theater, however, no one knew when they left.

Turman Wilson testified for a day-and-a-half in his own defense, explaining in detail what he and Utah did from March 19 to March 30, the day they were apprehended in Sacramento. He reiterated their alibi, claiming they were not in Vancouver on the day Dewey was abducted. Turman then launched into a complicated story involving several changes of automobiles and many trips between Washington and Oregon. He testified that he and Utah dodged the police for 10 days and fled to California, not because they were involved in Dewey’s kidnapping and murder, but because Utah feared revocation of his parole.

Utah Wilson was the next to testify, and his story mirrored Turman’s. He claimed it was their intention to avoid arrest from March 18 until April 10, 1950, at which time he was scheduled to see his probation officer, Frank A. O’Brien. Utah believed he could convince Officer O’Brien that he had nothing to do with the theft of the power saw, and therefore had not violated the terms of his parole -- except, of course, for leaving the jurisdiction of Clark County without permission, fleeing to Sacramento in the company of a convicted felon (Turman) and being arrested in possession of a loaded firearm. As for his fingerprints found on a beer bottle at the crime scene, the only explanation was that the police had set he and Turman up with a bottle removed from his garbage can.

Final arguments began on Wednesday morning, June 28, 1950 after Judge Cushing’s instructions to the jury. Prosecutor Jones gave an hour-long summation of the state’s case, emphasizing three points: Utah Wilson’s fingerprints were found on the beer bottle found at the crime scene, the defendants switched automobiles at least three times after the abduction, and their actions following the murder, such as hiding from the police and fleeing to California. In addition, the defense could not produce one witness who could prove conclusively the Wilson brothers were in the Playhouse Theater on the night and during the time the kidnapping occurred, rendering their alibi worthless.

Defense Counsel Goodman argued that none of the state’s witnesses had contributed any testimony or hard evidence linking either Turman or Utah Wilson to the kidnapping and murder of Jo Ann Dewey. No one who witnessed the abduction positively identified the defendants as the men who forced the victim into the car. The entire case was based solely on circumstantial evidence and mere suspicion. Goodman further charged that Clark County authorities failed to exert every effort and explore every clue in the murder investigation and the Wilson brothers were convenient scapegoats to cover up their ineptitude.

Verdict, Sentencing, and Appeals

The trial concluded on Wednesday afternoon, June 28, 1950, and the case went to the jury at 3:45 p.m. After deliberating for only five hours, the bailiff notified Judge Cushing the jury had reached a verdict. Court was reconvened and jury foreman Robert L. Davies announced that Turman and Utah Wilson had been found guilty of first-degree murder and kidnapping and the jury decreed the death penalty be inflicted upon each defendant for each offense.

On Friday, June 30, Judge Cushing sentenced Turman and Utah Wilson “to be hanged by the neck until dead” at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. Goodman moved for a new trial and an arrested judgment based on judicial error. After Judge Cushing denied the motion, Goodman notified the court his intention to appeal the verdict to the Washington State Supreme Court. The execution date was stayed until the appeal process had run its course. On August 2, 1950, Goodman filed a supplemental motion for new trial, citing newly discovered testimonial evidence material to the defense. The motion was denied, however, because it had not been filed within the prescribed time limits.

The Washington State Supreme Court heard the Wilsons’ appeal on May 10, 1951, ultimately deciding the court did not err in denying the motion for a new trial. Defense counsel immediately filed a petition for a rehearing which was denied on July 13, 1951. On Wednesday, July 18, 1951, the Wilsons appeared briefly before Judge Cushing at which time he signed the death warrants, designating Saturday, August 30, as their execution date. Goodman notified the court that he was filing an petition for a new trial with the U.S. Supreme Court.

On August 20, 1951, Associate Supreme Court Justice Hugo L. Black (1886-1971) ordered a stay of execution so the tribunal could consider the Wilson brother’s petition for a writ of review. The court denied the petition on October 15, 1951. In Vancouver, Judge Cushing rescheduled the execution for Friday, November 30, 1951.

Attorney Goodman immediately filed a petition for a rehearing and stay of execution with the Washington State Supreme Court, contending that certain evidence was suppressed in the trial, new evidence had been uncovered and the Wilsons had been deprived of their right of due process of the law. The court denied the petition on November 27, 1951.

On November 29, in a last-ditch effort to save the Wilsons, Attorney Goodman filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus and a stay of execution in U.S. District Court in Spokane. But Judge Sam M. Driver rejected the petitions, stating he had no jurisdiction in the matter. The Wilsons, however, did get an eleventh-hour reprieve from Judge William Healy of the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals in San Francisco who directed the prisoners “shall live to such time the that the Supreme Court of the United States, or justice thereof, shall direct.”

On March 11, 1952, Attorney Goodman sent another appeal for review of the Wilson case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court refused for the second time to hear the case and on May 9, ordered the prisoners returned to Clark County Superior Court for a third execution date. The Wilsons arrived in Vancouver from Washington State Penitentiary on Wednesday, May 21. The following day, it took Judge Cushing one minute to set the date, June 23, 1952, then they were on their way back to their cells on death row.

On Friday, June 20, 1952, U.S. District Court Judge Driver denied a second petition for a writ of habeas corpus and a stay of execution, again stating he had no jurisdiction in the matter. But he did grant a certificate of probable cause, permitting Defense Counsel to take the case back to the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

On Sunday afternoon, June 22, 1952, the Wilsons were granted an indefinite stay of execution by Appeals Judge Albert Lee Stephens to give the court time to determine if there was probable cause for appeal from denial of the writ of habeas corpus by Judge Driver. On Thursday, July 10, the court decided there was no probable cause and issued an order vacating the stay of execution. The Wilsons were promptly returned to Vancouver, where Judge Cushing set the fourth execution date, August 15, 1952, leaving their only realistic hope of escaping the death penalty a commutation by Governor Arthur B. Langlie (1900-1966) to life in prison.

Reprieve Upon Reprieve

Meanwhile, Erle Stanley Gardner (1889-1970), well known author of crime fiction and an attorney became involved in the case. He helped establish The Case Review Committee, an association of concerned lawyers whose purpose was to reopen and investigate cases where it was believed a defendant may have been incorrectly convicted of crimes they did not commit. The cases were published in Argosy magazine, featured as “ Court of Last Resort.” Gardner arrived in Walla Walla with two investigators, Thomas Smith, former warden at the Washington State Penitentiary, and Alex L. Gregory, former President of the American Academy of Scientific Investigators and expert polygraph examiner.

Although the investigators failed to uncover any new evidence, Gardner declared the results of the polygraph tests were positive and warranted an extrajudicial review of the case by a special committee of attorneys. In an unprecedented action, Governor Langlie acquiesced and on August 14, 1952, granted the Wilsons an executive stay of execution for 90 days. The governor reluctantly chose three attorneys from a list submitted by the American Bar Association: Erle Stanley Gardner, Altima, California.; Harlan S. Don Carlos, Hartford, Connecticut; Henry H. Franklin, Peterborough, New Hampshire.

The 90-day reprieve expired on November 15, 1952 and on Monday, November 24, 1952, the Wilsons journeyed back to Vancouver, where Judge Cushing set a record-setting fifth execution date for Saturday, January 3, 1953. (The previous record was four, held by Jake Bird, hanged in 1949). No other death-row inmate in Washington state’s history had experienced so many last-minute reprieves from the hangman’s noose.

Governor Langlie's Decision

On Friday, December 12, 1952, Governor Langlie’s office in Olympia finally received the special committee’s 27-page report on the Wilson case. “I will take my time reviewing the report and any other information that may come up,” the governor told the press. “I will keep my mind open until time to make the decision” (The Walla Walla Union-Bulletin). He said the text of the report would not be made public and he would not permit the press to interview the Wilsons before the execution date. Meanwhile, scores of petitions asking executive clemency for the brothers poured into the governors office.

On Friday, January 2, 1953, Governor Langlie announced the study by the special committee left no doubt the defendants had been given a fair trial and were guilty as charged. Concluding, the governor said: “The Wilson brothers now stand convicted of murder. They are no longer entitled to the presumption of innocence. In fact the presumption is now that they are guilty. Neither of them has done anything to overcome that presumption. On the contrary, they have, as the committee found, impeded the investigation by their persistent refusal to tell the truth regarding their movements on the night in question. It is my considered opinion that Turman and Utah Wilson are not entitled to clemency or a further stay and that the judgment pursuant to the jury’s verdict should now be permitted to take effect” (The Walla Walla Union-Bulletin).

The Execution

On Friday evening, Turman and Utah ate a lavish last meal, which included fried rabbit and chicken, giblet gravy, cranberry sauce, french fries, hot biscuits, cherry pie, devil’s food cake, ice cream, milk and coffee. At 11 p.m., the brothers were moved into an isolation cell where they were shaved and dressed in new clothes. Then Warden John R. Cranor read them the death warrant.

At midnight on Saturday, January 3, 1953, Wilsons walked 40 feet from the isolation cell to the gallows, accompanied by four prison guards where two traps had been constructed, separated by a curtain. The traps would be sprung by four guards who each pressed an electric button, one of which released the door. Black, cloth hoods were pulled over the prisoners heads, followed by hangman’s nooses. At 12:06 a.m., Turman Wilson dropped through the trapdoor without uttering a word. One minute later, the trapdoor under Utah Wilson was sprung, dropping him five feet to his death. The bodies were taken down at 12:16 a.m. and prison physicians Dr. Wilmer Unterseher and Dr. Ralph Keyes pronounced them dead.

Following the executions, Attorney Goodman released hand-written statements from the Wilson brothers, protesting their innocence. Prior to the Wilsons, Goodman had defended 21 people charged with capital crimes and saved every one.

Funeral services for Turman and Utah Wilson were held on January 7, 1953, at the Church of God in Fern Prairie. They were buried in the Camas Cemetery, 630 NE Oak Street, which overlooks the Columbia River. A group, insisting the Wilson brothers were innocent, asked permission to install a monument with the inscription “Here lie two innocent boys, victims of society.” The cemetery board denied the request.

A Bizarre Episode

In a bizarre episode, minutes after the double execution, Western Union telephoned Warden Cranor’s office advising a telegram had just been received from U.S. Senator Warren G. Magnuson (1905-1989). “Herewith is ordered a stay of execution of Wilson brothers by emergency decree, presidential authority delegated through me as U.S. Senator from Washington. Confirmation coming from Olympia” (The Walla Walla Union-Bulletin). Senator Magnuson was immediately contacted in Washington D.C., and denied having sent the message and Governor Langlie’s office said it had no knowledge of the telegram

Western Union reported the telegram had been called in from a pay-phone in a Seattle tavern at 11:30 p.m. The FBI assigned agents who identified the sender of the hoax telegram as Thomas E. Thomas, age 42, a furniture dealer. On January 8, 1953, Thomas was arrested and charged with impersonating a federal official. He was subsequently indicted by a federal grand jury on March 3, and convicted of the crime in U.S. District Court on November 19. On December 14, 1953, Judge William J. Lindburg sentenced Thomas to nine months in federal prison.

Turman and Utah Wilson were the 68th and 69th prisoners to be hanged at the Washington State Penitentiary since 1901, when the state legislature mandated that all executions take place at the prison. It was the second double execution in state history and the first time that two brothers had died on the gallows together. The first double execution was that of Walter Dubuc, age 17, and Harold Carpenter, age 35, who were hanged together on April 15, 1932 for the murder of 85-year-old Peter Jacobson, a Thurston County farmer.