The city of Bremerton, home to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard & Intermediate Maintenance Facility, was founded in 1891 by German immigrant William Bremer. The main part of the city is on the Kitsap Peninsula's Point Turner, approximately 15 miles west of Seattle. The history of Bremerton and that of the navy base have always been inextricably entwined, with the fortunes of the former highly dependent on the activities of the latter. Bremerton made it through the ups and downs of a military-dominated economy for most of the twentieth century, but barely survived the 1980s when almost every major business enterprise moved to Silverdale, and significant military spending was diverted to the new Trident submarine base at Bangor. The city managed to hold on through the 1980s and 1990s, and in more recent years took steps to reinvent itself and revitalize its economy.

The Suquamish

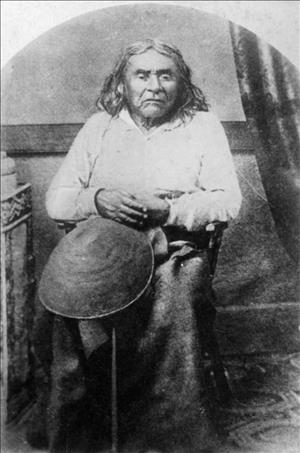

The Suquamish, or "people of the clear salt water" in the Lushootseed tongue of the Coast Salish linguistic group, established permanent winter camps on the islands and peninsulas of the central Puget Sound as long ago as 5,000 years. During the summer months they would decamp from their permanent settlements and travel by canoe to seasonal grounds to fish the rivers, hunt, and gather berries and other edible plants. Their primary settlement was Old Man House at present-day Suquamish, about 12 miles north and a little east of Bremerton.

The Suquamish had two great nineteenth-century leaders whose names live on today. The first was Kitsap (1780?-1860), a war chief who won renown in 1825 by leading an attack against the warlike Cowichan Tribe of Vancouver Island. Kitsap County and the Kitsap Peninsula honor his memory.

The other was Seattle (178?-1866), a nephew of Kitsap who was chief of both the Suquamish and Duwamish tribes when the full Denny Party arrived at Alki Point in 1853. Chief Seattle also had proved himself in battle against Native enemies, but was considered a true friend of the white settlers. At the urging of early settler David "Doc" Maynard (1808-1873), the hardscrabble little village of Duwamps on Elliott Bay was renamed after Chief Seattle in 1853.

Today there are approximately 950 registered members of the Suquamish Tribe, and about half of them live on the Port Madison Reservation. Although they still exercise their treaty rights to fish and gather shellfish at their traditional grounds, the tribe also operates the luxurious Suquamish Clearwater Casino Resort on the Kitsap Peninsula near Agate Passage.

Exploration and Exploitation

The first official American survey of the waters around present-day Bremerton was conducted in 1841 by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes (1798-1877) of the United States Exploring Expedition. It was Wilkes who named Point Turner, the peninsula where much of Bremerton and the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard are now situated, and he was struck by the suitability of the area for naval use:

"There is not in the world nor could there be a harbour superior to Port Orchard — Good anchorage, protected from every point with many little basins about the size of a Dry Dock but hard sandy bottom, into which a ship of the line may be hauled & left dry at low water. A pair of floodgates & a foundation would make a dry dock without any other expense or trouble" (Charles Wilkes and the Exploration of Inland Washington Waters, 176).

In the years following Wilkes's survey, white settlers started appearing in Puget Sound in increasing numbers. Among the first to homestead near present-day Bremerton were William Littlewood and Daniel J. Sackman, the latter of whom fathered four children by a Suquamish woman. Another early arrival was Captain William Renton (1818-1891), who built a sawmill on Alki Point in 1853 but relocated it to the Manette Peninsula the following year. His was the first industry of note in the area and the first sawmill, but many more were to follow, drawn by the seemingly endless expanse of virgin timber.

A Northern Navy Base

In 1877, Ambrose Barkley Wyckoff (1848-1922), a sickly young lieutenant with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, piloted the schooner Yukon on a hydrographic mapping voyage in upper Puget Sound and Commencement Bay. Wyckoff, like Wilkes, recognized the region's military potential. Upon returning to the East Coast in May 1880 he started what would become a long campaign to establish a naval base in the sheltered but roomy inland waters of Sinclair Inlet at the southern end of Port Orchard Bay.

Studies by two presidential commissions, one of which included Ambrose Wyckoff, concluded that the southern shore of Point Turner had everything necessary for a naval base: sheltered but deep water close to shore; abundant supplies of timber; unlimited fresh water from the region's many rivers; and huge fields of bituminous coal within just few miles of Seattle, itself easily accessible by water. The merits of the place overwhelmed all objections by advocates for other sites, and Congress, albeit with some reluctance and a pinched purse, finally allocated $10,000 for the purchase of land and an additional $200,000 to begin construction of a dry dock.

A Quick Buck or a Longer View

Within just a year or two of Wyckoff's 1877 visit, rumors were circulating that there would be major federal land purchases made in the area for a naval base. Homesteading loggers who had struggled for years to eke out a living now hoped that their property was worth many times what it would have brought just months earlier. The rumors came true, but the hope of a windfall generally did not. Ambrose Wyckoff was sent to buy the land, but with strict instructions to pay no more than $50 an acre.

The chasm between what the settlers thought their property was worth and what the government was willing to pay created opportunities for men who had a longer view of things. William Bremer (1863-1910) and Henry Paul Hensel (1871-1935), both of Seattle, reasoned that once the navy base was established -- indeed, even while it was being established -- it would need a town to support it, and that was where the real money would be made.

Bremer had the plan and Hensel, a Seattle jeweler and Bremer's soon-to-be brother-in-law, had the money. In February 1891, one month before Wyckoff arrived on his land-buying mission, the two purchased the original homestead claim of settler Andrew Williams, agreeing to pay close to $200 an acre for nearly 170 acres of land that Williams had sold to his son for $3 an acre not too many years earlier. The property was logged-off waterfront bordering Sinclair Inlet, right at the heart of the proposed navy base.

When Wyckoff came calling, Bremer and Hensel sold him 81 acres of the Williams property for $50 an acre, losing, on paper, over $12,000, but keeping property inland from the planned facility and on the point of the peninsula where Sinclair Inlet met Port Washington Narrows. On September 16, 1891, Wyckoff was appointed the first commandant of what was then called the Puget Sound Naval Station, and by June 1892 he had completed the purchase of a little more than 190 acres at the prescribed price of $50 per acre.

William Bremer's Town

While Wyckoff was busying himself buying up land for the naval base, Bremer, having obtained Hensel's interests, set about building a town next door. In September 1891 the navy raised the American flag over its land, and three months later, on December 10, Bremer filed a 25-acre plat for a new town named, somewhat immodestly, "Bremerton." The navy base and the town thus came into the world together, and their fortunes have been linked, in good times and bad, ever since.

One year later, in December 1892, work began on the station's first dry dock, a 650-foot-long "graving" dock capable of handling the navy's largest ships. While that was going on Bremer nurtured his new town by donating or selling at discount prices land for schools and churches. He also built Bremerton's first wharf at his own expense and helped numerous businesses get off the ground. But the financial Panic of 1893 slowed progress on the naval base, and this in turn slowed Bremerton's development. Dry Dock No. 1 was finally completed in 1896, but things only got worse. Federal funding dried up, and both the base and the town staggered through the remaining years of the nineteenth century.

Wyckoff to the Rescue

Health problems forced Ambrose Wyckoff's early retirement in July 1893, but he returned to the area in 1899 as a civilian, disturbed by reports of plans to close and relocate the naval base. Wyckoff enlisted the help of the Seattle business community, and the city's Chamber of Commerce prepared and submitted to Congress a persuasive report stressing the yard's importance to the regional economy. This had the desired effect; federal funding was greatly increased in 1900 and 1901, and the workforce at the base quickly grew from fewer than 150 to more than 600.

As the base prospered, so did Bremerton. Soon the town was sprouting businesses of all kinds. A weekly newspaper, The Bremerton News, started publication on June 8, 1901, and its first issue claimed that 24 new businesses and 70 homes had been built in the previous three months. The workforce at the navy yard supported a half-dozen general stores, at least 15 saloons, and a post office. There were rooming houses, a barber shop, a hotel, a laundry, two cigar stores, even a "shooting gallery." Culture was served as well, with the nearby Charleston Social Club featuring a performance by the "Bremerton Orchestra" (The Bremerton News, June 8, 1901).

Just a month later, in July 1901, a group of the town's citizens petitioned the Kitsap County Commissioners for incorporation. The lengthy list of voting-age residents who signed the petition did not include William Bremer, who continued to reside in Seattle. On October 2, 1901, the voters approved the incorporation of Bremerton as a city of the fourth class. The town's first mayor was Alvyn Croxton (1869-1941). An election in January 1902 returned Croxton as mayor and seated A. P. Stires, Thomas Driscoll (1845-1934), J. J. Kost, F. W. Coder, and C. Hanson as the town's first full five-member council.

In July 1902 a private company brought in Bremerton's first piped water through wooden mains. In August the first official volunteer fire department was formed, and the following December phone lines came in. William Bremer's plans seemed to be proceeding smoothly, but some serious trouble was brewing on the town's rowdy Front Street.

An Often Uneasy Affair

It was inevitable that Bremerton would attract businesses that catered to the less-savory inclinations of young sailors and transient workers. Prostitution, gambling, drunkenness, opium, muggings -- the panoply of human temptation and weakness -- were present from the beginning. By late 1902 Bremerton had a population of about 1,700, and there were 16 saloons, all within a short walk of the navy's front gate. It was a wide-open town, and less than a year after Mayor Croxton was elected the navy threatened to shut it down, warning that it would boycott its own shipyard in order to save its sailors from Bremerton's "gross immorality." An Olympia newspaper, under the headline "Too Bad for Them," reported:

"An official report received today from Rear Admiral Yates Stirling ... details a deplorable state of affairs in Bremerton, and Acting Secretary of the Navy Darling today issued an order that will have the effect of keeping naval vessels away from that station in future until the nuisance is abated.

Gambling resorts and disorderly houses, the report says, flourish just outside the yard, especially when one of the war vessels is in port ..." (Morning Olympian, December 31, 1902).

Mayor Croxton was quick to respond, issuing a statement on January 1, 1903, that said, in part:

"The report regarding Bremerton is an unqualified falsehood ... . There are no card sharks, bunco men, or bawdy houses in the town" (Morning Olympian, January 1, 1903).

With no apparent sense of irony, Croxton two days later announced that he would close all public gambling in Bremerton. This decision was not met with universal approval, even among members of the city council, nor was the navy overly impressed. It continued to issue threats and broadsides, and expanded the circle of blame to Seattle, describing it as

"a harbor for all of the bad elements of lumber camps, mining camps and seaport towns, and ... a degree of immorality exists there that is equal to that of any city in the United States, and much of this element works in Bremerton ... " (Morning Olympian, January 8, 1903).

The battle over vice pitted the U.S. Navy against Bremerton's gambling houses and saloons, with the mayor and council in the middle and fighting among themselves. Resolution seemed possible on February 2, 1903, when the council, at the persistent urging of Mayor Croxton, doubled the licensing fee for saloons and rescinded the licenses of the five or six drinking and gambling houses located nearest the base on Front Street (which was south of today's 1st Street). But a pro-saloon faction on the council managed to rescind the Front Street ban within weeks, and a short game of tit-for-tat was on.

Mayor Croxton next pushed through an ordinance that would cause all liquor licenses to expire on April 1, 1903; the council responded by automatically extending all licenses for an additional year. The navy chimed in, again threatening to pull out "unless every saloon is moved from Front Street" (The New York Times, May 25, 1903). This time the threat worked -- the pro-saloon coalition collapsed, and the council went the navy one better by revoking every liquor license in town, effective June 8, 1903. The ban of course did little to stop either drinking or gambling, but it did make it a little less obvious and a little more distant.

This Town for Sale

The navy's overbearing attitude and charges of rampant immorality really bothered William Bremer, who had put his money and his good name into the town, and by early fall of 1903 he'd had enough. His reasoning was simple: If the U.S. government wanted to dictate how Bremerton should be run, then the U.S. government should buy the damn town and run it. By September 4, 1903, Bremer had obtained powers of attorney from nearly all of Bremerton's commercial land owners and disclosed that his asking price was $350,000. Later that month he traveled to Washington, D.C., and offered Bremerton lock, stock, and barrel to the navy at the discounted price of $300,000. But the navy thought the price was still exorbitant; Bremer came home disappointed, and never tried again. Nor did his widow, or his children. Even today [2010], a significant part of downtown Bremerton is owned by a trust established by William Bremer's sons, John and Edward.

The ban on saloons and legal liquor sales stayed in place for about two years without significantly reducing Bremerton's overall sin quotient. But the navy was pacified, and quietly allowed a handful of liquor licenses to be issued. The entire state went "dry" in 1916, and nationwide Prohibition started in 1919. Sailors still got drunk in and around Bremerton, and gambling and prostitution did not disappear, but the city's leaders were no longer accused of being complicit.

Despite its somewhat raucous reputation, or perhaps because of it, Bremerton continued to attract new residents and businesses. The February 1909 issue of Coast magazine described the town:

"Bremerton has a population of about 3,000 souls, and is daily adding to its numbers. The business interests are large and increasing. On every hand is seen the widest activities in all lines of business. A large saw mill, ice and cold storage, lumber yards are located here and groceries, dry goods stores, boot and shoe stores, bakeries, restaurants, hotels, saloons and all kinds of business departments are numerous and thriving.

New, substantial brick and concrete business blocks, public halls, several hotels, one of which is a large three-story structure, and countless numbers of residences of a lasting and permanent nature are now under construction or just being completed" (Coast, p. 112).

The Second Decade and World War I

William Bremer died young, at age 47. On the day of his burial, December 30, 1910, Bremerton's businesses closed for two hours in the afternoon and the town's flags were flown at half-mast. His widow, Sophia Hensel Bremer (1872-1959), took over management of the family properties and with the three Bremer children she would continue to play an influential role in Bremerton for many years. One of the family's signature projects was the construction in 1914 of the Bremerton Trust and Savings Bank building on the northeast corner of 2nd Street and Pacific Avenue, one of three buildings in Bremerton designed by noted Seattle architect Harlan Thomas (1870-1953).

Employment at the yard reached 1,620 by the early summer of 1909, but the roller-coaster nature of an economy based on military needs became clear two months later when work slowed. The labor force was reduced by more than half almost overnight, only to grow to 1,500 again within a year, a pattern of ebb and flow that would be repeated with varying intensity for decades. And, of course, the population of Bremerton saw huge temporary spikes of military personnel -- in 1912 the Bremerton YMCA reported that it had been visited by 57,272 enlisted men.

World War I started to affect Bremerton two years before America's formal entry, when the navy yard began building submarines for Imperial Russia in 1915. (They were not completed before the Bolshevik Revolution, and were bought by the U.S. government to prevent them falling into communist hands.) By the time U.S. troops were sent overseas to fight in 1917, the yard employed 4,000, and that year money was allocated for a third dry dock. By 1918 employment at the yard stood at more than 6,500, most of whom lived on-base and all of whom spent money outside its gates.

Bremerton annexed the town of Manette, just across Port Washington Narrows, in 1918, but the two would not be connected by a bridge until 1930. The 1920 census showed that Bremerton's population had almost exactly tripled in 10 years, growing from 2,993 to 8,918. And although it had refused Bremer's earlier offer, the federal government in 1918 decided to buy up what had been Bremerton's "tenderloin" district, from Front Street down to the waterfront. Front Street disappeared behind the base perimeter, and it and its riotous days came to an end.

Heading for Depression

With peace went the booming prosperity of the second decade of the twentieth century, and Bremerton settled into a period of slower growth. Employment at the base tapered off from the wartime high of 6,500 to bottom out at fewer than 2,500 by 1927, but the town itself had grown to a point that many businesses could survive by serving the area's civilian population and the lessened needs of the military. Homes were being built, car dealerships opened, services expanded, and optimism prevailed.

Bremerton absorbed the next-door community of Charleston in 1927, further increasing its population and tax base. In 1928, construction began on the light cruiser USS Louisville, and employment at the naval yard jumped by 1,000, providing additional flotation to the local economy. In June 1929, just four months before the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression, Bremerton voters passed an $835,000 bond issue to improve the city's water system and to build an electrical plant.

In November, after the bottom fell out of the world economy, work began on a bridge linking Bremerton with the former Manette, now East Bremerton, financed almost entirely by public subscription. When the full effects of the Depression set in, Bremerton, perhaps inured to some degree by the previous economic ups and downs of the naval yard, actually managed better than most towns and cities.

Surviving the Thirties

The Manette Bridge opened to great fanfare in June 1930, and with that completed the people of Bremerton tackled the Great Depression. A Puget Sound Navy Yard Stabilization Bureau was established to lobby in Washington D.C., for shipyard work, and each worker at the yard pledged $5 a year to support its efforts. They also agreed to regular payroll deductions to help support Kitsap County's unemployed, and all employed workers in the county were asked to give up one day's pay a month for the same purpose.

The federal government did its part too, and the shipyard actually expanded during the Depression years. Concerns over Japan's actions in the Pacific led to orders for several new ships. County projects funded by the Works Progress Administration also helped. So successful were these combined efforts that Bremerton experienced record growth in 1934 and 1935, and by the end of the decade its population had increased by half, to over 15,000. By 1940, when the national unemployment rate was still well over 14 percent of the labor force, Bremerton's stood at just 6.9 percent. Bremerton was doing well, and in 1937 its incorporated status was upgraded to city of the second class.

Business was good enough that the Bremerton Chamber of Commerce, which had been in existence since 1907, saw fit to formally incorporate in March 1938. The incorporation papers were signed by its treasurer, William H. Gates Sr., grandfather of Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates. And during the late 1930s and early 1940s, Bremerton was also home to the controversial founder of the Church of Scientology, L. Ron Hubbard.

More War, More Work

The global disaster that was World War II was a huge boon to Bremerton almost from day one. Five of America's warships damaged during the Pearl Harbor attack of December 7, 1941, were towed or limped under their own power into what was then called Navy Yard Puget Sound for repair. Soon the city fashioned itself "Home to the Pacific Fleet," and its population ballooned to as many as 80,000, including more than 32,000 shipyard workers. With most working-age men being sent off to fight, they were replaced in the shipyard by wives and girlfriends, marking a major cultural shift and helping give rise to World War II icon "Rosie the Riveter."

Bremerton during this era was filled with young people, and with the shipyard running three shifts, dances were held at all hours of the day and night, including afternoon USO-sponsored affairs on the decks of dry-docked aircraft carriers. But housing all these new people was a challenge that was never fully met. Two housing developments, Westpark and Eastpark, were built early in the war by the federal government and a third, Sheridan Park in East Bremerton, somewhat later, but they didn't nearly fill the need. Tents and trailers abounded, and people lived in converted garages and chicken coops. "Hot-bedding," in which workers on different shifts would alternate sleeping in the same bed, was common. By the end of the first full year of war Bremerton had 69 apartment houses, four hotels, three hospitals, six theaters, six dance pavilions, and nearly 6,000 students enrolled in its schools. Also in 1942, Bremerton's incorporation status was upgraded again, to city of the first class.

With this latest boom, and with Prohibition no longer the law of the land, alcohol, gambling, drugs, increased crime, and other social ills again became more visible. The city's police force increased from 12 officers to 54 during the course of the war. But this time there were no threats to pull work away from the shipyard; it was simply too critical to the war effort, and a certain tolerance took hold during those years of crisis, especially for the occasional indulgences of sailors on leave.

One controversy that did cause friction with the federal government was the Bremerton Housing Commission's practice (which it denied at the time) of separating black and white workers and families in allocated housing. The federal census counted only seven "negroes" in Kitsap County in 1940, but by 1945 the number exceeded 4,500. Although Bremerton had largely shunned the resurgent Ku Klux Klan during the 1920s, there was still a deep strain of white fear and bigotry. During the war years, most African Americans, and virtually no whites, were assigned to live in the Sinclair Park area of West Bremerton, and many downtown businesses posted "Whites Only" signs. Well-known Bremerton activist Lillian Walker (1913-2012), the wife of a shipyard worker, started her long career in civil rights in 1941 by organizing protests at the navy base against such discrimination. Despite these actions and steady pressure from the federal government, the practice of de facto segregation persisted after war's end, and it took until the 1960s for the last vestiges of overt racism to recede.

On December 1, 1945, the name of Navy Yard Puget Sound was changed to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, and with the end of World War II Bremerton had reason to worry about its future. A labor force that had peaked at 32,000 was reduced to 9,000 by the end of 1946, and the estimated 80,000 peak population of the war years dropped to 27,678 in the 1950 census. But there were a few bright spots. In 1946 the Bremerton School District opened Olympic Junior College (now Olympic College) and admitted 575 students to its inaugural class, and in 1948 its first graduates were honored with a visit by President Harry S. Truman (1884-1972). The state took over operation of the college in 1967 and still runs it today.

Then, once again, Bremerton was helped by war. North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, and the yard was put to work recommissioning mothballed warships. The respite was temporary -- when a truce was signed in July 1953, Bremerton entered an extended period of stasis, to be followed three decades later by a steep decline.

Doing Without War

With the huge population decrease after the war, Bremerton found itself with too many buildings for too few people, and it showed. The economy was not particularly bad during the 1950s, but the city took on a somewhat desolate and semi-abandoned air simply because it had been overbuilt during the war years.

City tourism got a boost in 1955 with the coming of the famed USS Missouri, on the deck of which the Japanese had signed their formal surrender on September 2, 1945. The Iowa-class battleship stayed in Bremerton as part of the Pacific Reserve Fleet before being reactivated in 1985. Bremerton fought to get the "Mighty Mo" back when she was again retired in the 1990s, but the venerable battleship ended up in Honolulu.

By the 1950s the Manette Bridge, despite being partially rebuilt in 1949, had become totally inadequate for the traffic volumes across Port Washington Narrows. In 1958 the four-lane, $5.3 million Warren Avenue Bridge was completed about a half mile to the northeast of the old span. (In 2011 the 1930 Manette Bridge was demolished. Its replacement span was completed in 2012.)

The days of wars fought with vast navies seemed over, and the government's demand for new ships diminished. The Puget Sound yard did build two guided missile frigates in the late 1950s and kept fairly busy refurbishing existing ships. But it was not enough to fuel growth, and the 1960 federal census showed that Bremerton's population shrank slightly in the preceding decade.

Years of economic ups and downs had made city leaders quick on their feet, and one of their most ingenious moves was the annexation of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in 1961. This was done by simply extending the city's eastern boundary to the center of Sinclair Inlet, thus encompassing the base. Mayor H. O. Domstad (1909-1991) was not at all coy about the reasons for the annexation. With 10 ships due to arrive at the base by April 1961, the mayor calculated that the move would add at least 10,000 military personnel to the city's official population. Since the state distributed $13.18 per person per year to its cities, Bremerton would reap more money at a time that it was badly needed.

A Series of Unfortunate Events

At the end of the 1960s, Bremerton could be proud that it had survived and largely prospered for seven decades, through war and peace. But in the last three decades of the twentieth century the town hit a patch of bad luck that almost brought it to its knees, and from which it has yet [2010] to fully recover. An indication of how bad things were can be found in the population figures. In 1970, Bremerton's population was 35,301. Thirty years later, it had increased by less than 2,000, to 37,259.

Even at the start of the 1970s, thing were not rosy: The unemployment rate in King County was 6 percent; Bremerton's was almost double that, at 11.9 percent, and every slight downward tick in that number represented not a new job, but the migration of another working family. William Brenner's son John, who had managed the family's extensive holdings in downtown Bremerton, died in 1969, and his younger brother, Edward, was a poor manager. Leases expired and weren't renegotiated; necessary upkeep and repairs went undone; even the valuable waterfront property owned by the family sat largely unused except for parking cars.

A major blow came when the federal government selected Bangor, located on Hood Canal about 12 miles north of Bremerton, as the home port for the first squadron of Trident nuclear submarines. The Bangor facility, which had served as a humble ammunition depot from 1942 until 1973, suddenly became the new center for military construction and spending on the Kitsap Peninsula. The demand for labor to convert the old depot to a modern submarine base drew workers and their families away from Bremerton and toward Silverdale, which stood about half way between Bremerton and Bangor. After adding nearly 10,000 residents between 1960 and 1970, Bremerton grew by less than a thousand over the next decade.

At Silverdale, a sleepy little unincorporated community in central Kitsap County, a subsidiary of the Safeco Insurance Company started building the huge Kitsap Mall. It opened in 1985 and quickly replaced Bremerton as the dominant commercial center for the entire Kitsap Peninsula. The J. C. Penney store was first to pull out of downtown Bremerton and move to Silverdale, and this led to more defections. Sears, Montgomery Ward, Nordstrom Place Two, Woolworth, and Rite Aid all closed their downtown Bremerton stores in the 1980s and early 1990s, and soon the commercial core of the city consisted of street after street of empty windows staring out from empty spaces. Edward Bremer died in 1987, and the properties were placed in a trust controlled by Olympic College, which seemed equally unable to do anything to break the downward spiral.

The death of Bremerton's commercial district had many causes, but to many the primary blame belonged to the family that gave the city its name. Wally Kippola, a past president of the Kitsap County Historical Society and former director on the Central Kitsap School Board, told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1998:

"What drove people to Silverdale and out of Bremerton was the parochial attitude of (the late) Bremer brothers (John and Ed), whose father founded Bremerton and who owned most of the property there" (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 20, 1998).

That may have been a harsh judgment, but it was more than a little true. It is a sad irony that a city started through the initiative of one generation of Bremers was nearly destroyed by the ineptitude or inaction of the next.

Signs of Life

In June 1977 the Bremerton city council passed a resolution designating virtually the entire urban core of the city a "blighted area," a first step to obtaining expanded powers for urban renewal under state law, including enhanced powers of eminent domain and taxation. Much of the "blighted area" was still in the hands of the Bremer family, and Bremerton clearly was fed up with Edward Bremer's unwillingness or inability to make better use of his holdings.

Twenty-five years later, little had been done. The J. C. Penney building and most of the downtown core still sat vacant. In January 2003 a city ordinance acknowledged that "conditions have not changed since those designations (of blighted areas) to warrant repeal of said designations ..." (Bremerton City Ordinance No. 4830). In 2000, Bremerton voters had rejected a ballot proposal to create a recreational center in the downtown area, and the Bremer Trust, established by the brothers, had maintained for years that it wasn't economically feasible for it to subdivide large commercial buildings for rental to multiple small businesses.

But the logjam was actually loosening. In 2001 the city adopted a Downtown Revitalization Plan. The following year, the city council appointed the Kitsap County Consolidated Housing Authority to oversee the city's community renewal efforts. In 2003, ground was broken for the Norm Dicks Government Center and City Hall, and it opened its doors in November 2004. In that same year, the adoption of a Comprehensive Plan gave additional impetus to the city's revitalization efforts. Also in 2004, a conference center with a hotel, restaurant, offices and shops opened next door to the ferry terminal, and another hotel and a tunnel to redirect ferry traffic from downtown streets were under construction.

The arts are being seen to, as well. In July 2005, Bremerton's city council passed an ordinance establishing the Bremerton Arts Commission and enacting a "1% For Arts" program which requires all city-funded capital improvements to allocate 1 percent of their construction cost to support public art projects. A downtown Arts District centered on 4th Street and Pacific Avenue hosts monthly "First Friday Arts Walks," and there are also "Last Saturday Arts Walks" in the Charleston district of West Bremerton. The downtown Arts District features several fine galleries, three museums, two performing art stages, unique shops, various restaurants and cafes, and clubs featuring jazz and other live music.

Among the art on permanent display are the sculptural fountains of Harbour Fountain Park and at least four other public sculptures, one of which, a two-part piece entitled "Fish and Fisherman," has not been free of criticism since its installation in 2010 on diagonal corners at 4th and Pacific. But disputes about the merits of individual art works aside, the welcoming civic atmosphere, city-sponsored programs, relatively low prices for commercial space, and a core of established artists, galleries, and workshops should ensure that Bremerton's art scene continues to make major contributions to the city's eclectic personality.

A major boost came in late 2007, when the Bremer Trust agreed to sell the long-vacant J. C. Penney building to Ron Sher, a Seattle developer. Sher announced plans to create a new downtown commercial center, with a bookstore, health facility, restaurant, residential units, and a large commons area for community use. Also in 2007, the city opened the 2.5-acre Harborside Fountain Park as part of its Harborside Redevelopment Plan, and in May 2008 the Port of Bremerton dedicated a greatly expanded 300-slip marina.

Once again, however, events much larger than Bremerton's local concerns conspired to hamstring the city's economy and stymie its redevelopment plans. The global financial crisis that started in 2008 slowed or halted progress on several proposed projects, including the redevelopment of the J. C. Penney building, and many slips at the new marina remained unfilled. But there was one big difference this time, and reason for optimism. Bremerton had to look beyond its historical reliance on the military and by 2010 the city had on its books a detailed blueprint for urban revitalization and a more durable and stable economic footing.