Throughout much of the twentieth century, Washington state's public port districts pursued a single mission: economic development. They dredged out waterways, filled in wetlands, built infrastructure, and actively courted industries and the jobs they could bring to local communities. Smokestacks were signs of progress; unfilled wetlands were resources going to waste. Beginning in the 1970s, a series of new laws and regulations forced the ports to consider the costs as well as the benefits of unfettered growth. The transition was not an easy one, but eventually port districts began to take on leadership roles in environmental cleanup and restoration, including cleaning up properties they themselves had polluted. Today, many Ports tout their stewardship of the environment almost as much as their contributions to the economy.

The very characteristics that made ports effective as engines of economic growth also equipped them to move to the forefront of environmental protection. As municipal corporations, ports have the power to tax, issue bonds, and exercise eminent domain (the right to acquire private property for public use). As entities created specifically for the purpose of stimulating commerce, they are imbued with entrepreneurial spirit. They operate in the sphere of what political scientist David Olson has called "public enterprise." The combination of governmental power and business acumen allows ports to respond to environmental problems in ways that other public agencies (with no expertise in developing or managing property) and private enterprises (limited by the demands of the bottom line) are unable to attempt.

Expansion Mode

The Washington Legislature authorized local voters to create publicly owned and managed port districts in 1911. The first such districts were simply seaports. They focused on maritime activities -- dredging waterways and building wharves, docks, storehouses, and facilities to transfer freight from rail to water transport. Over the next 60 years, the Legislature steadily increased the powers available to port districts, leading to an expansion in both the number of ports (more than 80 were established eventually, 75 survive as of 2010) and the range of their operations.

One important step came in 1939, when ports won the right to establish Industrial Development Districts (IDDs): designated areas within an overall port district where special taxes could be levied to pay for utilities, roads, rail lines, waterways, and other facilities to attract industries. The Legislature also allowed port districts to build and operate airports (1941); made it easier to organize IDDs by removing limits on the use of eminent domain and allowing ports to issue local improvement bonds to finance industrial development (1955); and authorized the creation of port districts in areas with no access to bodies of water (1959). Two other measures increased the authority of port commissioners while reducing voter control. The first, enacted in 1941, restricted the circumstances under which voters were required to approve port bond issues. The second, two years later, eliminated the requirement that voters approve the comprehensive plans used to guide each port’s development.

With expanded powers and fewer encumbrances, ports were able to move quickly on property acquisition and construction projects. The Port of Tacoma, for example, dredged a deep waterway to recruit large industrial tenants for a development district on former tideflats in Commencement Bay. The Port of Vancouver established an industrial site on the Columbia River and invited the Alcoa Aluminum Company to build a smelter on it. The Port of Kennewick developed the Hedges Industrial Area, stretching along some 50 miles of Columbia River shoreline and home, by 1958, to four major chemical plants. These and other projects greatly extended the commercial and industrial reach of Washington state’s public ports in the years after World War II.

New Era of Regulation

The ports faced few regulatory limits until the 1970s, when Congress and the states began passing new environmental protection laws in response to concerns about air and water pollution, loss of natural habitats, threats to the survival of certain species, and other issues.

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which took effect in 1970, set up the mechanism for Environmental Impact Statements and led to the creation, in 1971, of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Legislature established the Washington Department of Ecology (DOE) in 1970 and the following year enacted the Washington State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA), which required state and local agencies to consider the environmental consequences of a proposed project before approving a permit for the project. The federal Clean Air Act of 1970 and the Water Pollution Control Act of 1972 limited industrial discharges into the air and water. The Endangered Species Act of 1973 required the conservation of habitat deemed critical to the survival of threatened or endangered plants or animals, including, significantly for ports, fish.

By 2000, according to the Washington Public Ports Association (WPPA), there were 14 separate state and federal laws that applied to environmental issues involving ports. Of these, the one with arguably the single greatest impact was the Washington State Shoreline Management Act (SMA) of 1971. The law, administered by the Department of Ecology, strictly limited new development within 200 feet of the shoreline along the state’s many miles of tidal waters, rivers, and lakes. As originally proposed in an initiative sponsored by the Washington Environmental Council, the SMA would have protected land within 500 feet of the shoreline and made conservation a priority. Port districts, represented by the WPPA, joined developers and other business interests and persuaded then-Governor Dan Evans (1925-2024) to offer an alternative initiative, which reduced the protected zone to 200 feet and gave water-dependent commercial and industrial uses equal ranking with conservation. Voters chose the alternative measure.

Even as modified, the SMA required ports to make major changes in their operations. For example, it made the provision of new or expanded public access a condition of virtually every new shoreline permit. And, together with amendments to the Clean Water Act in 1977, it brought an end to the days when port districts could dredge and fill wetlands -- the mud flats and marshes at the land-water interface -- at will.

Adjustment Period

Port officials did not readily embrace these new restrictions. For example, in the mid-1970s, the Port of Grays Harbor ignored objections from environmentalists and pressed ahead with plans to increase the depth of the 20-mile-long shipping channel through Grays Harbor from 30 feet to 48 feet. Studies at the University of Washington concluded that the project would cause large-scale damage to marine life in the estuary. But the greater question was what to do with the "dredge spoils" -- the 20 million cubic yards of sediment that would be removed from the bottom of the harbor. The Army Corps of Engineers (the federal agency responsible for the dredging itself) planned to dump most of the material at sea. Port manager Hank Soike (b. 1921) wanted it used as fill for tidelands in Bowerman Basin, the largest shorebird feeding area remaining at Grays Harbor. "It’s a waste of a natural resource to dump spoils in the open ocean," he said (Brown, 83).

About a fifth of the basin’s intertidal mudflats and salt marshes had already been filled in and converted to industrial use through earlier dredging operations. Soike, hired as manager of the port in 1974, was eager to expand and diversify the port's operations. Like many of his peers, he regarded wetlands as little more than mosquito-breeding swamps, valuable mostly for their potential as prime industrial property. "Throughout Washington state’s history ports have shown a trend for securing lands adjacent to public terminal facilities," the League of Women Voters noted in a 1989 study. "... dredging and filling activities were viewed by port decision-makers as long-term planning activities to secure the economic future of the port district by providing space for industrial development" (Washington State Public Port Districts, 32).

But times had changed. Wetlands had come to be recognized as having essential ecological functions, including flood control, filtering pollutants from streams, recharging groundwater, and providing critical habitat for fish and wildlife. The so-called Deep Dredge at Gray’s Harbor was scaled back to a depth of 38 feet instead of the proposed 48; and the spoils were barged to an open water disposal site near Westport, Washington, instead of being used as fill. In 1988 -- the same year that Soike left his position port manager -- Congress set aside 1,500 acres of the remaining wetlands in Bowerman Basin by creating the Grays Harbor National Wildlife Refuge.

Port officials eventually made peace with the SMA and even came to regard it as a tool for good public relations. "This regulatory mandate provides ports with excellent stewardship opportunities that can enhance a port’s relationship with its community," the WPPA pointed out in a 2001 handbook for port commissioners. "Port Commissioners are encouraged to communicate with their community regarding the port’s stewardship role, which can be demonstrated by shoreline public access such as shoreline parks, picnic areas, and other public facilities coordinated with economic development projects" (Environmental and Land Use Handbook, 9).

Battles Over Dredging

The very nature of their activities put port districts in the middle of some of the most contentious environmental issues of the late twentieth century. Seaports operate in the environmentally sensitive region where land and water meet. Other ports are located in estuaries (where fresh and salt water mix), at the bottom of river basins, or along the shorelines of navigable rivers. As sources of pollution (from logging operations, agriculture, storm runoff, municipal sewage, and industrial discharges) move downstream, they accumulate in sediments that settle out at the bottom of harbors. Industrial activities on land developed by ports that are far from any navigable water can produce toxins that permeate the ground and leach into groundwater.

Ports with waterways rely on dredging to maintain and, at times, deepen shipping channels and harbors. Dredging itself disturbs aquatic ecosystems and the fisheries that depend on them. If the bottom sediments are contaminated, digging them up can release heavy metals and toxic chemicals into the water column, where they can enter the food chain, potentially harming not only fish but the humans who eat them. Dredging also causes short-term increases in turbidity, which can adversely affect the metabolism of many aquatic organisms.

Disposing of the excavated material, whether contaminated or not, creates another set of problems. Wetlands, once a preferred site for dredge spoils, are now protected in many areas. Ocean dumping is associated with some of the same harmful effects as dredging, including turbidity and dissolved toxins. Disposal in an approved landfill is expensive. The situation is so complicated that the Army Corps of Engineers for the Seattle District operates a Dredged Material Management Office (DMMO), dedicated solely to administering a Dredged Material Management Program (DMMP). Since 1988, the Department of Ecology has hosted a Sediment Management Annual Review Meeting (SMARM) to deal with issues related to dredging.

Concerns about both the costs and the environmental impact led to years of delay for a major dredging project on the Lower Columbia River. In the late 1980s, the Army Corps of Engineers (at the behest of the ports) proposed deepening the 106-mile-long shipping channel from Astoria to Portland and Vancouver by five feet, to a depth of 45 feet. The goal was to allow ports on the lower river to accommodate fully loaded "Pan-max" vessels: deep-draft ships of the maximum size that can navigate through the Panama Canal. The existing channel was not deep enough to allow such ships to leave the ports with capacity loads of grain and other cargo. "As it is, some of the Pan-max vessels can come up lightly loaded but going back down river, they end up having to leave a lot of grain that they could carry if the channel were a little deeper," Don Wagner, director of the Washington Department of Transportation’s regional office in Vancouver, explained in a 2004 interview. But cutting five feet from the bottom of the channel would require the excavation and disposal of millions of tons of mud and rock. "One of the problems is that you have to do something with the material you dredge out," Wagner said, "and where do you put it? You can’t use it to fill in wetlands anymore. You have both marine life and land-based issues" (Wagner interview).

After years of controversy and legal challenges, a modified project (deepening the channel by three feet instead of the originally planned five) was finally completed in late 2010. The total cost was $202 million, $30 million of which came from an infusion of federal economic stimulus money in the spring of 2009. "Those stimulus dollars amounted to a rare windfall for proponents of the project," the Longview Daily News commented in an editorial. "Representatives of this and other port communities have had to battle opponents of the project in court and scratch for funding every step of the way" (March 17, 2010).

Other Environmental Challenges

Washington’s port districts face dozens of other environmental challenges, from noise pollution at airports to leaking underground storage tanks (or LUST, in EPA shorthand). The force of propellers on large vessels can stir up contaminated sediments in harbors and shipping channels, increasing the likelihood that hazardous chemicals can dissolve in the water and poison fish and other organisms. Ocean-going container ships sometimes arrive in port loaded with ballast water picked up in a distant port of call and used to stabilize the ship before it takes on a full cargo. If it is discharged in a local port, the water can introduce invasive species that may thrive in the new environment, crowding out native plants and animals. Washington law now requires ships to pump out old ballast at a site at least 50 nautical miles from shore and replace it with local seawater before coming into port, but severe weather sometimes prevents such an exchange.

Air pollution is another issue at many ports. As The Seattle Times pointed out in a 2006 story, modern seaports are driven by diesel. A single freighter idling in a port can produce as much diesel pollution as 2,300 semi trucks driving down the highway. Both freighters and cruise ships use auxiliary diesel engines to provide electrical power while they are docked. The cranes that load containers onto trucks and trains are powered by diesel. As a result, according to a Times analysis of EPA data, the most unhealthful air in the state is found, with few exceptions, in neighborhoods near ports in Western Washington.

Brownfields

Perhaps the greatest of all these challenges is cleaning up "brownfields" -- land heavily degraded by industrial or commercial use and often abandoned by those directly responsible for the contamination. Reclaiming such properties protects the environment, reduces blight, and takes development pressure off "greenspaces" (open land). It is also technologically difficult -- toxins are far easier to detect than to safely remove and dispose of -- and reclamation can be prohibitively expensive. The process "presents special opportunities as well as constraints," as the WPPA put it (Environmental and Land Use Handbook, p 23).

In recent years, federal agencies have turned to port districts for help in cleaning up brownfields because their structure and authority allows them to take action in cases where the private sector or local governments may not. In 2003, for example, EPA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) selected the Port of Bellingham as one of three ports (along with those in Tampa, Florida, and New Bedford, Massachusetts) to participate in a program called Portsfields, to rehabilitate contaminated sites in port and harbor areas.

In the first stage of the Bellingham project, old creosote structures and contaminated sediments were removed from the site of an inactive and dilapidated boatyard; natural wetlands were restored, and the property redeveloped. The project received a national award for environmental mitigation from the American Association of Port Authorities. "The Port of Bellingham takes its environmental stewardship role seriously and we are pleased to receive this national recognition," said Port Commissioner Scott Walker. "This is an example of a project that combines environmental cleanup and habitat creation with job creation, which is what we hope to do throughout the waterfront" (Port of Bellingham news release, 2005).

The Port of Seattle also received a national award, at the 2004 Brownfields National Conference in St. Louis, Missouri, for its work in cleaning up Harbor Island. The 480-acre manmade island was created by private developers at the mouth of the Duwamish Waterway in the early 1900s. It was designated an EPA "Superfund" site in 1983 because of the concentration of lead, mercury, zinc, arsenic, petroleum products, dioxins (byproducts of chemical manufacturing and metal processing), polychlorinated byphenyls (PCBs), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the soil and groundwater. In 2001, the EPA added the entire Duwamish Waterway to the Superfund list. As much as four feet of sediment at the mouth of the waterway was contaminated with volatile organic compounds, heavy metals, PCBs, and other chemicals -- the result of decades of discharges of industrial and municipal wastes.

Under an agreement with the EPA, the Port demolished a lead smelter and a metal processing facility on the island; excavated the most contaminated soils and moved them to an approved hazardous waste landfill; removed lead-containing dust and paint; and paved some areas to minimize dispersion of pollutants. The Port also restored habitat in two sites along the waterway. The cleanup allowed the Port to move ahead with a $300-million, 90-acre expansion of Terminal 18 (on the east side of the island), nearly doubling the size of the terminal and adding a new dockside intermodal rail yard, two new truck gates, a larger container storage yard, and other amenities to improve cargo handling capabilities. "We take our stewardship of the environment very seriously," said H. R. (Mic) Dinsmore, Chief Executive Officer of the Port of Seattle from 1992 to 2007. "Beyond the economic benefits this expansion brings to our region, it also gave us the means to clean up contaminants that might otherwise have remained in the environment for many years" (Port of Seattle news release, 2002).

Stewardship and Sustainability

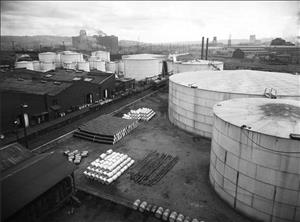

Port officials today use the phrase "environmental stewardship" almost as often as "economic development" in discussing their activities. The WPPA points to numerous projects, and millions of dollars in expenditures, in which port districts created or preserved critical habitat, reduced pollution run-off, cleaned up contaminated shorelines and groundwater, and provided public access to waterfronts. Some recent examples: a 12-acre habitat peninsula created by the Port of Everett; salmon-rearing pens operated by the Port of Grays Harbor; an old tank farm and industrial tideflats cleaned up by the Ports of Pasco and Tacoma; and an extensive shoreline access system developed by the Port of Seattle.

The Port of Seattle boasts that it is "Where a Sustainable World is Headed." The Port of Tacoma is currently (2010) involved in five separate mitigation projects that will restore a total of 25 acres of freshwater and intertidal marsh, forested upland, and riparian habitat along Hylebos Creek. The Port of Vancouver ("The Port of Possibility") has remediated 55 acres of contaminated property since the mid-1990s. With the recent purchase of the site of the old Alcoa aluminum smelter, it is committed to reclaiming an additional 218 acres of brownfields. The Port of Everett plans to become "A Committed Port, a Cleaner Port!" by using an Environmental Management System developed by the EPA and the American Association of Port Authorities to promote air and water quality, energy conservation, recycling, and wildlife preservation.

Beyond good citizenship, ports have economic motivations for environmental stewardship. Neighbors of ports in Los Angeles and Oakland, California, have recently won lawsuits over issues of pollution on port property. In 2003, in the biggest case to date, residents near the Port of Los Angeles halted a major expansion and forced a $60 million settlement that included commitments to reduce air pollution. "We want to stay ahead of this issue," Port of Tacoma spokesman Mike Wasem told The Seattle Times, "and we don't want to be in a position where we are not seen as a benefit to this region" (February 23, 2006).

Local ports have tried to clean the air by installing anti-pollution equipment on cranes or replacing old cranes with cleaner-running models. Some have switched to using lower-sulfur diesel or a blend of regular diesel and vegetable-based biodiesel in cargo-hauling equipment and vehicles. At the Port of Seattle, two large Princess Cruises ships can now shut off their diesel engines and plug into the city’s electrical system while docked. The Port has also begun offering truck owners $5,000 or the blue book value of older trucks in return for scrapping them and buying newer, cleaner models. As of July 2010, 200 trucks had been taken off the road through the Scrappage and Retrofits for Air in Puget Sound (ScRAPS) program.

Balancing Act

This focus on sustainability is relatively new. When the first public ports were organized a century ago, their chief objective was to keep private companies from monopolizing waterfront transportation. Only in the face of increasing public and governmental pressure did port districts begin to try to balance economic goals and environmental values.

The districts are becoming more adept at blending federal, state, and local environmental mandates, but it’s a challenging task. Representatives of 15 different state, tribal, federal, and local stakeholders were involved in the Port of Bellingham’s Portsfield project. Almost any construction project on port property can be ensnared in a welter of regulations. Port officials complain that there is little coordination between the regulating agencies, resulting in many unnecessary delays and sometimes in the loss of business opportunities.

The Port of Seattle summed it up this way: "If we want to dredge or perform in-water construction, we must get a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers with comments from the EPA, the National Marine Fisheries Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, several state agencies, and local Indian tribes, who have very unique and specific rights regarding the state’s fisheries resource and have a voice in deciding whether such fisheries will be impacted by a project and whether the port must make compensation for that impact. In addition, we must get a water quality certificate from the Washington Department of Ecology with comments from the Washington Department of Natural Resources, the Washington Department of Game, and the Washington Department of Fisheries. That’s for in-water projects including dredging. It’s a different set of regulations for uplands shore construction" ("Ports at a Glance," p 22).

Port officials demonstrate less patience for the process when economic conditions tighten. And despite new environmental sensitivities, the core mission of port districts remains the promotion of commerce and industry. "I think it's premature to give up and say, all we can have is marinas and waterfront parks," said Charles Sheldon (b. 1947), a former executive at the Port of Seattle, hired as executive director of the Port of Bellingham in October 2010. And the ambitious plans to continue restoring habitat and redeveloping contaminated areas in the port’s 220-acre Central Waterfront District? "I'm not sure the money's there to do the work," he said (Bellingham Herald, October 4, 2010).