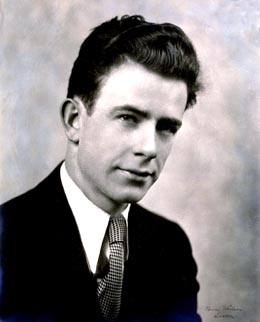

John L. O'Brien was a state representative from southeast Seattle whose 26 terms in the House spanned the terms of nine governors. His service was highlighted by four two-year terms wielding a powerful and effective gavel as speaker in the partisan political roiling of the early 1960s. Appointed in 1939, he remained in the House -- but for a 1947-1949 hiatus -- until 1993. A master parliamentarian and durable politician, he served in every leadership capacity: Speaker, Speaker pro-tempore, minority and majority leader, and on every major House committee. Rainier Valley born and raised, O'Brien was a civic leader who energetically chaired local events and sponsored legislation to meet the needs of a district that changed from the Irish and Italian community of his birth to a more diverse one of Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, African American, Orthodox Jewish, Vietnamese, East Africans. and Latinos. In his honor the House office building in Olympia is named the John L. O'Brien Building.

Early Years

John Lawrence O'Brien was first of three boys and a girl born of James and Mary O'Brien. His father emigrated from Ireland in 1904 and his mother in 1907, and they met in Seattle. James joined the Seattle Police Department shortly thereafter, and was promoted to detective. By 1920, the young family lived in a frame house James was still finishing on Findlay Street in the Rainier Valley's Hillman City development.

On January 21, 1921, James O'Brien was shot dead by a cop-killer on the streets of Seattle in a celebrated case that cut down the family's bright prospects and deeply affected the 9-year-old John. The effects would remain for the rest of his life.

There was a crosstown funeral procession, community grief, and sympathetic outcry for the family. Although neighbors pitched-in and finished the O'Brien house, the family, reliant on a meager police pension, was thrust into near poverty.

The Irish Catholic community was close in the Rainier Valley, and O'Brien attended Catholic elementary schools, St. Edward and O'Dea. The family home was near St. Edward Church, and the O'Briens were close to the nuns and priests there. It was a proximity that was never to change in John O'Brien's long life.

His father's abrupt death affected his life in at least two ways: It did not make him a "law and order" conservative; and it did give him a deep empathy for pensioners. According to his daughter Karen, his devotion to the formal traditions, continuity, and rules of the church, his community, and the House of Representatives can be traced back to his reaction to that tragic day that so suddenly and utterly changed his world.

Early Involvement in Business and Politics

John grew up working to help the family, living in his mother's house until the age of 41. He graduated from business school and earned a degree in accounting by attending classes at St. Martin's College. He became a certified public accountant, set up an accounting firm, and kept his CPA license until age 92. O'Brien also found time to establish a heating-oil business on Rainier Avenue.

He met his future wife, Mary Schwarz, at St. Edward's Church. He became a father at 42, and had his sixth and final child at age 55. They are John O'Brien Jr., Laurie O'Brien Jensen, MaryAnn Suver (1958-2008), Karen O'Brien, Jeannie O'Brien, and Paul O'Brien.

His interest in politics was sparked in 1928 after another Irish Catholic, Al Smith, ran for president. After some Democratic Party grassroots work in his neighborhood district, and helping a friend run for office, O'Brien was persuaded to run for state senate in 1938. He was opposed in the primary by a young up-and-comer named Albert D. Rosellini (1910-2011) later to become two-term governor. O'Brien lost to the better known, better organized Rosellini.

A Seat in the House

In 1939, O'Brien's work in the grassroots paid off; he was appointed to succeed a representative who had died. Although he hadn't served a day in Olympia, in 1940 he was able to run and easily win the House seat as the incumbent Democrat in the solidly Democratic district. He kept that seat for nearly 50 years.

The freshman O'Brien entered the Legislature at a time when the left and right wings were squabbling within the Democratic caucus. Speaker Edward J. Reilly (1906-1953), a conservative Democrat from Spokane, had to mediate between them every morning before the session convened. He took O'Brien under his wing, letting him sit in on these daily, oft-heated negotiations. On occasion, he gave the gavel to O'Brien to make routine procedural motions at the rostrum. This experience instilled in O'Brien something that was to become key to his career: the importance of mastering the rules. At the end of this first session he knew he wanted to be Speaker of the House.

Ambitious, he ran for the Speakership in 1943 against his one-time mentor, Ed Reilly. He lost, and there were no hard feelings, but his candidacy brought him media and peer attention as a serious legislator. He ran again in 1945, and lost again, but threw his support, to help install the winner, Olympia Representative George F. Yantis (1885-1947). The grateful new Speaker put him on the powerful Rules Committee, a goal of O'Brien's from the beginning. Yantis also let him preside over the House in his brief absences.

A Bump in the Political Road

In 1946, O'Brien's ambitions were thwarted. He lost the Democratic primary by 23 votes to Charles M. "Streetcar Charlie" Carrol (b. 1907-1985). He credited the loss to "overconfidence" and neglecting his own campaign. "I defeated myself, more or less," he said (Chasan).

In 1948 however, lesson learned, O'Brien put in all his energy, raised the necessary funds in the primary campaign, and won the primary. Winning the election was a given for a Democrat in his district, and this time in the final tally, he led the ticket. The win ended the only break in his legislative career. Elections for the next four decades were pro forma.

Speaker O'Brien

Doggedly pursuing the prize, O'Brien ran unsuccessfully for Speaker in the 1949 and 1950 sessions. The way was cleared for him in the Democratic Caucus in 1952, but the party lost the majority in the Eisenhower Republican landslide so he was Minority Leader.

In 1954 House Democrats were back in control with a one-seat majority, enough to give the Democrats the speakership. O'Brien had spent a year collecting impressive endorsements, and traveling the state visiting House Democrats in their districts and building his candidacy. After 14 years, and a brief skirmish with the powerful Julia Butler Hansen, (1907-1988), O'Brien's principle legislative goal was achieved in the 1955 session.

House Speaker John L. O'Brien was a conservative man, within his caucus and in his demeanor. He wielded a sharp-tongued, partisan gavel. He was powerful, and gathered more power -- not by glad-handing or persuasion, but by developing a deep understanding of Reed's Rules of Order, and skillfully working the levers of House machinery. He ran a tight -- some said autocratic -- ship. He didn't like surprises, and with careful parliamentary planning and staging, using rules he himself had made, he suffered few. He rarely associated himself with specific issues; it was about mastering the process and delivering the goods. O'Brien was a strict parliamentarian not known to be conciliatory or impartial, but by all accounts, he was fair.

Eventually, he won the grudging respect of Republicans as he presided over a frequently rambunctious body. Governor Dan Evans (1925-2024) admits that, as a freshman member, he was a little frightened of the austere O'Brien. He never forgot when O'Brien, gaveling him down in a heated debate, actually broke the gavel, and threatened to throw him out of the room.

Slade Gorton (b. 1928), a Republican who was to become Attorney General and a U.S. Senator, entered the House at the apex of O'Brien's power in 1959. He said, " [He] still remains in my mind as the model of an efficient and effective presiding officer ... . I have never, from that day to this seen a better one" (Chasan, tribute dinner program).

The Legislation Machine

These skills meant that O'Brien, through his leadership, achieved many Democratic legislative victories. In thousands of bills over the decades, he championed graduated income tax, public power, kindergartens, and pensions for police and firefighters. He oversaw the 1957 legislation setting up Century 21, the Seattle World's Fair.

Although the idea had to go to voters to be realized, O'Brien went to the mat in 1957 for a bill creating the Municipality of Metropolitan Seattle (Metro) a Seattle-based grouping of sewer districts that would later clean up the polluted Lake Washington, and eventually take over public transportation.

He worked for the Rainier Valley with legislation creating Genessee Park, and renovating Franklin High School. He sponsored legislation allowing the City of Seattle to charge admission to the lakefront for the annual Seafair hydroplane races, a move which, though unpopular, saved the event.

Growing Disaffection

By 1961, O'Brien, serving an unprecedented fourth term as Speaker, had accumulated some enemies: a gang of Republican young Turks led by Laurelhurst Representative Dan Evans; a brawling Democratic caucus, with certain members who wanted his job; and legislators from both sides representing special interests, especially those of private power. Through this unfriendly terrain, O'Brien had to do the heavy lifting for some unpopular bills presented by Governor Al Rosellini. These forces, fueled by what many felt were his heavy hand at the rostrum, were to end the era of Speaker John O'Brien.

It was the public v. private power fight, a key issue throughout his legislative career, that proved to be the coup de grâce.

The session closed that year after a bitter fight and epic four-day filibuster that O'Brien was able to finally extinguish by using a quick and heavy gavel on a dubious "aye" vote to adjourn, turning on his heel, and walking out of the chamber. Private power interests were represented in the House by Republicans (led by Evans) and a small group of Eastern Washington Democrats. Chasan writes: "Lingering bitterness over the power fight and the earlier fight over the Speakership would soon have repercussions both for O'Brien and the Democratic Party. ... The opponents did not fold their tents and slip away" (p.116).

That summer, Democratic Representative William "Big Daddy" Day, a Spokane chiropractor and staunch advocate for the private power industry, led the Spokane delegation out of the party convention complaining that "a group of hardcore ultraliberals had succeeded in getting control of the party ..." (Chasan).

O'Brien and most House Democrats considered Day a renegade and his walk-out a stunt. They never doubted his ultimate defeat in any attempt to take House leadership. They were wrong. Voters' disaffection with the party's pro-public-power platform plank and with Seattle-centric Democratic leadership was real. Bill Day became the Democratic front for a disciplined coalition of Republicans led by Dan Evans and dryside Democrats with sympathies to private power spurred on by a well-financed lobby.

The Epic Showdown

After the 1963 session was gaveled to order, it took the coalition but three votes to defeat a stunned O'Brien. On the second ballot, seven Democrats flipped from O'Brien to Day; a third ballot, 47 (of 48) Republicans swung to the conservative Democrat. James Dolliver (1924-2004) later Governor Dan Evans's administrative assistant and a state supreme court justice told O'Brien biographer Chasan it was: "the only time I saw John out-flummoxed. He didn't realize what was happening until the knife went in" (Chassan).

Falling from that pinnacle of power so suddenly was at first a difficult transition. And not only for O'Brien: It took years for the bitterness and acrimony of the coalition and associated political struggles to subside in Olympia.

Before he lost the Speakership, his name had been mentioned as a gubernatorial possibility, as well as a Seattle mayoral possibility and a 7th District congressional candidate. Rival Dan Evans and his cohort went on to higher offices, but O'Brien loved the House. He was long invested in it as an institution and in his beloved Rainier Valley district. He was to keep his seat for an unprecedented tenure.

Elder Statesman

For many sessions O'Brien was elected Speaker Pro Tempore, a position that allowed him to regularly take his favorite position: presiding over the House. He wielded the gavel from 1973 until 1981; again from 1983 to 1993. He took the gavel twice as Acting Speaker: in 1976, when dissident Democrats dumped Speaker Leonard Sawyer (b. 1925) and in 1980 when co-Speaker John Bagnariol (1932-2009) was indicted (and later convicted) after an FBI sting in the notorious political scandal known as "Gamscam."

Until departing the chamber in 1993, following his defeat by Jesse Wineberry (b. 1955) in the 1992 Democratic primary (when redistricting forced the two Democratic incumbents to run in the same district), John O'Brien served as the institutional memory and keeper of House rules and traditions. As House elder statesman, O'Brien tutored freshmen legislators on parliamentary procedure.

Even with his deep involvement in Olympia politics, O'Brien was always a big part of his Rainier Valley community. For 52 years, he was general chairman of Pow Wow (1939-1992), the popular south end Seafair event, held at Seward Park each year. Partnering with the South Seattle Crime Prevention Center, he wrote legislation addressing graffiti and gang activities; he worked with such neighborhood organizations as the Urban Business Association and Leschi Community Council to assure the state's new Interstate 90 had adequate access to the South End.

O'Brien was a self-described "New Deal Democrat" and was sometimes more conservative than his Seattle Democratic peers, but his effectiveness and integrity were never questioned.

On St. Patrick's Day, 1989, O'Brien's peers in the House renamed the House Office Building the John L. O'Brien Building.

John L. O'Brien died in Seattle at the age of 95 on Sunday, April 22, 2007. The state legislature was in session throughout that weekend, and O'Brien died within hours of its adjournment sine die. The House and Senate were notified of his passing, and in a fitting farewell the lieutenant governor and members of the House broke from their business to speak in his memory.