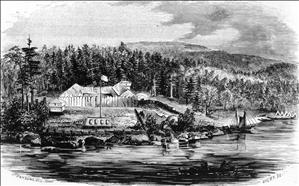

On October 16, 1813, facing an uncertain future due to the War of 1812, Pacific Fur Company agents, known as Astorians after company principal John Jacob Astor (1763-1848), meet at Fort Astoria and agree to sell all of their properties in the Northwest, including posts on the Columbia, Okanogan, and Spokane rivers, to the rival North West Company, a Canadian concern with headquarters in Montreal.

Worries and the War of 1812

Ever since January 1813, when they had learned of the outbreak of the War of 1812, Pacific Fur Company employees in the Northwest had feared for their future. At a meeting at Fort Astoria in late June 1813, the agents had discussed the likelihood that British naval blockades would prevent their annual supply ship from leaving New York. They decided that their best course of action would be to close their posts the next spring and journey overland to St. Louis and on to New York. To conserve their dwindling resources, Duncan McDougall (178?-1818), the senior partner on the Columbia at the time, had reached a non-compete agreement for the ensuing months with John G. McTavish (ca. 1778-1847), head of the North West Company's Columbia Department, headquartered at Spokane House (near present-day Spokane).

On October 7, 1813, McTavish arrived at Fort Astoria with a retinue of clerks and voyageurs. He carried a letter sent by express canoe from Montreal the previous May, informing him that the North West Company supply ship Isaac Todd was enroute to the Columbia, escorted by a Royal Navy frigate sailing under orders "to take and destroy every thing that is American on the N. W. Coast" (Elliott, 48). According to the sailing schedule supplied by the Montreal agent, the ships might arrive at the mouth of the Columbia any day, and the Nor'Westers had come to meet them. Gabriel Franchere (1786-1863), one of the Pacific Fur Company clerks working at Astoria, recorded the arrival of the Canadians in his journal:

"Mr McTavish visited us and gave us a letter addressed to him by Mr A. Shaw, one of the agents of the North West Company, in which this gentleman informed him that the Isaac Todd had sailed last March [1813] from London in company with the English frigate Phoebe, which was coming under government orders for the express purpose of taking possession of our post, which had been represented to the Lords of the Admiralty as a colony established by the American government on the banks of the Columbia River" (Franchere, 129).

This was not McTavish's first trip to the coast to greet the Isaac Todd -- he had paddled down the previous spring and waited several weeks, but she had not appeared. This time, however, he had verification that she was actually at sea, and he apparently felt that her imminent arrival, and the nature of her escort, gave him certain leverage, for on October 8 he approached the three Pacific Fur Company partners then present at Fort Astoria -- Duncan McDougall, Donald Mackenzie (1783-1851), and John Clarke (1781-1852) -- and "proposed purchasing the goods and Furs belonging to the company, here (as well as in the Interior) for cost and charges, excepting Articles damaged and in use" (McDougall, 220). In addition to Fort Astoria, the holdings of the Pacific Fur Company included Fort Okanagan on the Columbia, Fort Spokane on the Spokane River, and small outposts on the Clearwater, Clark Fork, Kootenai, and Thompson rivers.

A Haughty Manner

There is no record of the reaction of the three partners to this offer, but Alfred Seton (1793-1853), an Astorian clerk, wrote in his personal journal that the Nor'Westers' "object in coming down is to establish the country, and to drive us out of it. This will not be very difficult to effect, as our business has already been given up these six months and every arrangement since that time has tended to our leaving the country; they make their demands though with a high hand & certainly conduct themselves in a haughty manner at their camp" a short distance from the fort (Seton, 127).

Apparently the Astorian leaders decided not to press the issue of sovereignty, for Seton noted that the Nor'Westers "display 2 British colours, while on our side this is the first Sunday that out flag has not been displayed" (Seton, 127). The tension between the two camps was exacerbated by the fact that many of the Astorians were Canadian citizens who had signed on with Astor's company in hopes of making their fortunes.

Striking the Stars and Stripes

The American-born clerks and workers, according to Washington Irving (1783-1859), "felt indignant at seeing their national flag struck ... and a British flag flowing, as it were, in their faces. They had been stung to the quick, also, by the vaunting airs assumed by the Northwesters. In this mood of mind, they would willingly have nailed their colors to the staff, and defied the frigate" (Irving, 483). Alfred Seton, a native of New York, chafed at the indignity of striking the Stars and Stripes, but qualified his patriotic outrage with realism: "It does not become me to say much on this subject," he wrote, "as perhaps before long myself with the other Americans here will be prisoners of war or at any rate will be obliged to pass through their territories to reach our homes" (Seton, 127).

Gabriel Franchere agreed that the Astorians had few options, "situated as we were, expecting every day to see a warship arrive to deprive us of the little we had, we listened to their proposals and after several consultations set a price upon our furs and our remaining merchandise" (Franchere, 129). On October 12, an entry in the post journal noted: "Came to an understanding with Mr. McTavish respecting the disposing of the whole of the Company's goods, Merchandise, & Furs to the N. W. Company" (McDougall, 221).

Pacific Fur Company Death Warrant Signed

The ink was barely dry in the post journal, however, when John Stuart (1780-1847), another North West Company partner, arrived at Astoria with the rest of the Nor'Wester brigade from the interior. Upon learning of the agreement between McTavish and the Astorians, Stuart objected. According to McDougall, Stuart felt that McTavish had agreed to pay too high a price for the Pacific Fur Company's goods and furs, and wanted a deduction. But, McDougall wrote, "it being however our determination to accept of nothing less than what would be considered as fair prices, by disinterested persons, our Conference was at an end" (McDougall, 221). Two days later, however, the representatives of the two companies met again and "finally settled upon the terms the property would be disposed for and the time of receiving payment" (McDougall, 221).

By October 16, duplicate copies of the Bill of Sale of Pacific Fur Company to the North West Company had been copied by hand. The four articles of the agreement specified an inventory of the American posts, the delivery of payments, and arrangements for paying the overdue salaries of the Pacific Fur Company workers and for free passage for any Canadian citizens who wished to return to Montreal. Article 3 made provisions for McTavish and Stuart to hire any Astorians who might choose to remain in the region and were willing to transfer their loyalty to their former rivals.

The last article detailed the valuations that would be applied to dry goods, trade goods, boats, tobacco, ammunition, horses, buildings, and pelts. Seven clerks from the two companies witnessed the signatures of Duncan MacDougall on behalf of the Astorians and John G. McTavish and John Stuart for the Nor'Westers. Alfred Seton observed that "the Pacific Fur Company's death warrant has been signed. Now that & all its possessions in this Country, belong to the NW Company, who have purchased them at a fair price" (Seton, 129).

Not everyone felt that McDougall had negotiated a fair price, or indeed that he had been justified in selling the company at all. McDougall later insisted "that he made the best bargain for Mr. Astor that circumstances would permit; the frigate being hourly expected, in which case the whole property of that gentleman would be liable to capture" (Irving, 486).

But after learning of the sale John Jacob Astor indicated that he would have preferred capture to capitulation: "Had our place and our property been fairly captured, I should have preferred it; I should not feel as if I were disgraced" (Irving, 486).