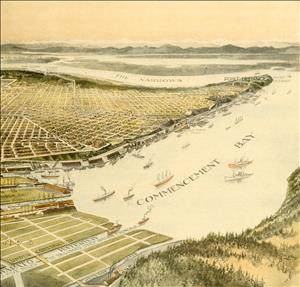

On May 31, 1919, Pierce County voters approve the "comprehensive scheme" of development prepared for the newly formed Port of Tacoma by consulting engineer Frank J. Walsh. The Port, which was created in a November 1918 vote, will inaugurate shipping at its first pier on March 25, 1921. Over the next nine decades, the Port of Tacoma will become a leading container port, serving as a "Pacific Gateway" for trade between Asia and the central and eastern United States as well as the Northwest, and handling most of the maritime commerce between Alaska and the lower 48 states. With ample room to expand on the tideflats fronting the deep waters of Commencement Bay, the Port will develop multiple waterways accommodating the largest ocean-going cargo ships and will create efficient intermodal transportation connections between ships and road or rail, often right on the dock.

Second Try Succeeds

Longshoremen, business leaders, and politicians from Tacoma were prominent in the ranks of reformers who in 1911 won passage of Washington's Port District Act, authorizing local voters to form public port districts to acquire and improve harbor facilities necessary to retain and expand maritime trade and commerce. But a year later, when proponents placed on the November 1912 ballot a proposal to create a public Port of Tacoma encompassing all of Pierce County, the measure was narrowly defeated. City voters supported the proposal, but many rural residents feared that a port would only benefit urban businesses.

In 1918, as the Tacoma waterfront hummed with activity generated by World War I, port proponents tried again. W. H. Paulhamus, a state senator and president of the Puyallup and Sumner Fruit Growers' Canning Company, gained rural support by arguing that a public port could build a cold-storage building on the waterfront, making it easier for farmers to preserve and ship their produce. Steamship company executives and other businessmen advocated for the port measure, as did the Tacoma Daily Ledger and longshore union members.

This time voters across Pierce County were convinced and they approved creation of the Port of Tacoma on November 5, 1918. Edward Kloss, Charles W. Orton, and Chester Thorne were elected port commissioners. They hired engineer Frank J. Walsh to create the "comprehensive scheme of harbor improvement" that the Port District Act required. Under the law, county voters had to approve both the harbor plan and the bonds that the Port would have to sell to fund construction.

Planning and Building

Walsh prepared a plan for harbor development on 240 acres of land along the Middle Waterway, where he recommended that the port's first two piers be built. The port commission placed the plan, and a measure authorizing the sale of $2.5 million in bonds to fund it, on the ballot for May 31, 1919. Voters approved both measures by fairly wide margins. However, support for the port bonds was weaker outside Tacoma, and it was several days before it was clear that the bond measure had barely, by a few hundred votes, surpassed the required 60 percent threshold.

Construction began on March 25, 1920, and exactly one year later the Edmore arrived at the newly finished Pier 1 to take on the first cargo shipped from the Port of Tacoma. Port business grew so quickly that within a year the commissioners approved a 300-foot extension of Pier 1. By 1923 Pier 2 was completed. During the 1920s, the Port's cargo tonnage doubled. By the end of the decade, at least 25 steamship lines made regular stops in Tacoma.

The Port Commission worked throughout the decade to build the promised cold-storage plant that had helped persuade voters to approve the port. The plant opened in 1931. In the meantime, voters in 1928 approved a new port bond issue allowing construction of a grain elevator that began operation in 1930.

Depression and War

When the Depression hit Tacoma's waterfront, cargo tonnage dropped sharply. Tacoma's maritime commerce rebounded somewhat after Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) became president. Roosevelt's New Deal reforms gave unions more clout than they previously had. When employers refused collective bargaining, longshore and other shipping-industry unions shut down ports on the entire West Coast in the great waterfront strike of 1934. Federal arbitration settled the strike in favor of the longshore union, creating the union hiring hall that still exists. Although significant, the hiring hall victory did not directly affect the Tacoma longshore locals, which were fully closed shop even before the strike, the only large longshore unions on the coast to enjoy that distinction.

The Depression slowed the Port's development until the 1939 state legislature gave public ports new powers to develop industrial sites. Port of Tacoma commissioners were among the first to take advantage of the new authority, setting up an Industrial Development District south of 11th Street between Hylebos Creek and Milwaukee Way. The Port began to recruit tenants, but World War II put the project on hold.

Like so much else, the Tacoma waterfront was largely given over to the military effort from 1942 to 1945. Thousands of troops from nearby Fort Lewis were dispatched to the Pacific theater from Port of Tacoma piers. Longshoremen were busier than during the Depression, but not all found full-time work, due in part to the fact that Seattle took the lion's share of the region's army and navy business. Increased mechanization on the docks also reduced the number of longshore workers needed, as the military spent freely on new equipment like forklifts and larger cranes.

A Key Advantage

After the war ended in 1945, the Port, like the rest of the country, faced a rocky transition back to a civilian economy. With the massive war mobilization over, waterfront manufacturing declined sharply. Maritime trade fell by 90 percent in 1946, to well below pre-war levels. The Port of Tacoma Commission responded to the nationwide downturn by renewing its interrupted efforts to attract manufacturers to the Industrial Development District it had established before the war. But even after Purex, Concrete Technology, Stauffer Chemical, and Western Boat Building all set up shop in the Industrial District, the port had not returned to pre-war business levels.

In the early 1950s, the commissioners embarked on further improvements to attract more development. They dredged the Industrial Waterway, located on the tideflats between the Puyallup River and Hylebos Creek and Waterway, to accomodate larger ships. In 1955, the commission hired Tibbetts-Abbett-McCarthy-Stratton (TAMS) to prepare a detailed comprehensive plan for future port development. The study proposed making maximizing a key competitive advantage: The Port of Tacoma's significant acreage on the deep waters of Commencement Bay was one of the few locations in Puget Sound where industry had direct access to deep water. The TAMS plan called for the Port to extend and widen the Industrial (later Blair) Waterway and Hylebos Waterway and construct ship-turning basins adjacent to the Industrial District at the ends of the lengthened waterways.

Mechanization and Modernization

In 1957, Tacoma longshore workers ended a 20-year rift by voting to affiliate with the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), headed by Harry Bridges (1901-1990). As ILWU members, Tacoma workers were parties to the Mechanization and Modernization Agreement that Bridges and the ILWU negotiated with West Coast shipping and stevedoring management. The agreement gave employers freedom to introduce both "mechanization" (labor-saving machinery) and "modernization" (work rules requiring greater efficiency) in return for a commitment of no layoffs and a guaranteed 35 hours of work (or pay) per week.

The agreement opened the way for employers to take advantage of two new, more efficient cargo-loading methods being developed during the 1950s. Bulk ships carrying large cargos of loose material like grain or ore were loaded and unloaded by large hoses that sucked or blew the material from ship to storage or vice versa. Container ships allowed most other cargo to be loaded into a large box (20 or 40 feet long) at the factory or warehouse, hauled by truck or train to the dock, and lifted aboard ship by crane.

Bulk and container ships were not yet common on the Tacoma waterfront when the agreement was ratified in 1961, but signs of change at the port were clear as dredging cranes and landfill reshaped the tideflats while warehouses and manufacturing shops were constructed for newly arriving businesses. Kaiser Aluminum reopened the aluminum smelter it had originally constructed on the tideflats in 1941.

New Leadership

In 1964, the port commission hired Ernest L. "Roy" Perry as general manager. He served until 1976, completing the expansion of the Blair and Hylebos Waterways called for in the TAMS plan and bringing the Port of Tacoma into the container age. The Port built new warehouses and piers for container cargo at Terminal 4 near the mouth of Blair Waterway and at Terminal 7 on Sitcum Waterway. The Port of Tacoma entered the container business in 1970, when the first container crane was built at Terminal 7.

Two prominent alumina domes -- sometimes termed the "original Tacoma domes" -- were also built at Terminal 7, to store ore for use at the Kaiser smelter. Pierce County Terminal was constructed at the head of Blair Waterway, where large amounts of storage space allowed the terminal to handle special cargo like locomotives, military equipment, and logs; the terminal also served as the first major center for the growing number of automobiles imported from Asia through Tacoma.

In 1968 Perry increased the Port's investment in industrial property by acquiring 500 acres in Frederickson, an unincorporated area of Pierce County 13 miles south of the port's Commencement Bay terminals. Over the years Frederickson has developed as a major industrial center.

During the 1970s, Tacoma continued to be a major exporter of forest products, as it had been since its founding. Two new export facilities were built in 1972 and 1973: Blair Terminal, with two berths for log exports, was followed by Weyerhaeuser's $4.5 million, 25-acre wood-chip facility on Blair Waterway. In 1975, the Port significantly increased its capacity to handle another leading export, grain, by building the Continental Grain Terminal, with a capacity of three million bushels, on Commencement Bay north of downtown Tacoma.

Rapid Growth

Worldwide trade increased at record rates in the 1970s, much faster than its growth in prior decades. Growth was particularly rapid at the Port of Tacoma, much of it in trade with Pacific Rim countries, whose share of Washington state trade rose steadily. After 1979, when the 30-year American trade embargo was lifted, the People's Republic of China joined Japan, Taiwan, and Korea as major trading partners for the Port of Tacoma. By 1982, the Port had tripled tonnage moved and quadrupled revenues over the levels of a decade earlier.

The Port of Tacoma's domestic trade also increased exponentially in the 1970s. Local 23 longshoremen worked with Port management to convince Totem Ocean Trailer Express (TOTE), a leading shipper to Alaska, to move its operations from Seattle to Tacoma. TOTE's first ship began calling at Terminal 7 in 1976 and the company added a second vessel in 1977.

The Port of Tacoma helped pioneer a new phase in trade and transportation history in 1981 when it opened its North Intermodal Yard, the first dockside railyard on the West Coast, located on the main port peninsula between the docks of Terminal 7 on Sitcum Waterway and Terminal 4 on Blair Waterway. The success of the Port's pioneering intermodal connection led to expansions and upgrades of the North Intermodal Yard throughout the 1980s. The Port also opened the South Intermodal Yard, immediately across E 11th Street from Sitcum Waterway, and the new intermodal connections helped fuel the Port of Tacoma's rapid growth during the 1980s. In subsequent decades, the Port built new dockside intermodal yards in conjunction with two new terminal projects, Washington United Terminals and Pierce County Terminal.

New Arrivals

After the giant container line Sea-Land announced in 1983 that it would move from Seattle to Tacoma, the Port designed and built the $44 million Sea-Land Terminal on Sitcum Waterway, and constructed a new terminal for TOTE's Alaska service to make room for the Sea-Land container terminal. Within weeks after Sea-Land's first ship docked in 1985, another large container shipping company, the Danish line Maersk, arrived. (In 1999, Maersk bought Sea-Land's international shipping business, creating Maersk Sealand, the world's largest container shipping operation, which remained a major shipper from Tacoma until moving to Seattle in 2009.)

In 1988, K Line, from Japan, became the third large container line in three years to begin serving Tacoma. The additional container ships brought further growth to the Port's intermodal yards. In 1987, the old United Grain Terminal, one of the Port's earliest projects (which closed after the larger Continental Grain facility opened), was demolished to allow expansion of the North Intermodal Yard to handle the increase in container traffic K Line would bring.

The Port continued to grow as the 1990s opened. In 1991, another major container shipper, Taiwan's Evergreen Line, began serving the Port's Terminal 4. The new arrival helped the port reach the one-million-container mark that year for the first time in its history. Before the Port could develop the upper Blair Waterway to handle the increasing number of cargo ships, a replacement had to be found for the Blair Bridge, which carried E 11th Street over the waterway. The drawbridge opening of 150 feet, more than adequate when the bridge was built in the 1950s, was too small for the giant container ships of the late twentieth century. In 1997, the replacement route via State Route 509 was opened, allowing the Blair Bridge to be removed and unlocking the upper Blair Waterway for development.

That same year Hyundai Merchant Marine entered a 30-year lease for the first container terminal to be built on the upper Blair Waterway. Opened in 1999 and named Washington United Terminals (WUT), the facility included the Hyundai Intermodal Yard. Container volumes set records in four of the next seven years, increasing by 62 percent overall.

Transition and Progress

The Tacoma tideflats' transition away from large manufacturing continued as the Kaiser Aluminum smelter, which had at its peak employed hundreds of workers, closed in 2000 due to increasing power costs and the effects of a long strike. Although the loss of jobs hurt the local economy at the time, the 96-acre Kaiser property soon became a key part of the Port's future development plans.

The attacks that occurred on September 11 had lasting effects on the Port as on the rest of the world. Beginning in 2002, the Port of Tacoma, along with other ports in Puget Sound and around the country, received federal grants to test and upgrade security at the ports and to improve "supply chain security" from the point of origin abroad to the final U.S. destination.

The Port's plans for expansion on upper Blair Waterway received a major boost in 2003, when Evergreen Line agreed to lease a new container terminal to be built at the head of the waterway, replacing the old Pierce County Terminal that had handled bulk cargo. Until then, some container shippers had doubts about the accessibility of the two-mile-long waterway, but with Evergreen in place others soon expressed interest. The new 171-acre, $210 million Pierce County Terminal and Intermodal Yard, which the Port built for Evergreen over the next two years, was the largest construction project in Port history.

In October 2003, the Port opened the $40 million, 146.5-acre Marshall Avenue Auto Facility, which could store and process nearly 20,000 vehicles at a time. Two months later, the one-millionth Mazda imported through the port drove off a transport ship at Blair Terminal and made its way to the Marshall Avenue facility.

The year 2005 brought a chain reaction of new terminal openings. In January, Evergreen Line moved to the newly opened Pierce County Terminal. In July, the new Husky Terminal, at Evergreen's former Terminal 4 location, doubled the presence of K Line at Tacoma. And in October, the Port completed the Olympic Container Terminal, an expansion of K Line's prior home at Terminal 7.

Facing the Future

The three new terminals, and continued increases in imports from Asia, especially China, led to two more record-setting years: volume topped two million containers for the first time in 2005 and rose further to set an all-time record in 2006. After that, Tacoma's container volumes declined, with the sharpest drop being from 2008 to 2009, as world-wide cargo traffic slumped due to the recession following the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble. The economic downturn also caused the Port to put some plans for expansion on hold. In 2007, when the Port and NYK Line of Japan entered an agreement for NYK to begin service to Tacoma in 2012, the plan was to construct a new container terminal on the east side of Blair Waterway. Those plans were altered and now call for NYK ships to use an existing terminal when they begin calling in 2012. By late 2010 and the start of 2011, container traffic appeared to be rebounding, as existing shippers increased service, with K Line bringing new, larger ships to Tacoma and Evergreen resuming routes it had suspended during the downturn.

Meanwhile, the Port continued to plan for the future. As it readied property for development when the economy improved, the Port proceeded with major environmental projects, including clean up of former industrial sites and wetland restoration along its waterways, planning to spend nearly $40 million by 2015. In 2010, the Port of Tacoma became the first in the Pacific Northwest to provide shore power for cargo vessels. The shore power plug installation at the TOTE terminal allows TOTE cargo ships to shut off their diesel engines while docked, reducing emissions by as much as 90 percent.

More than 90 years after its creation by the voters of Pierce County, the Port of Tacoma continues to transform the landscape of Commencement Bay and the economy of the region and to play a major role in international and domestic trade.