In May 1970, Seattle (along with much of the nation) was in the midst of weeks of protests that erupted when U.S. forces entered Cambodia on May 1. Protests escalated after National Guardsmen fired on a demonstration at Kent State University in Ohio, killing four students, on May 4. On the 5th and again on the 6th thousands of protestors blocked Interstate 5 through Seattle. James Knisely was present when demonstrators and police in riot gear faced off on the freeway for the second time, as he recalls in this memoir.

The Day I Saved Seattle by James Knisely

May 6, 1970: a birdsong balmy, lovely afternoon; the day I saved Seattle.

The tragedy that was Vietnam was in its deepest throes, but the power of the flower was showing us the way that makes for peace. Even so, the way was steep and beset with dangers. Two days earlier, four college students had been slaughtered by a handful of college-age Guardsmen on the usually quiet campus of a university in Ohio, and the national mood had grown jumpy. I was still stunned and still wondering what was becoming of us: first the mayhem of riots in Watts and Chicago, and now the madness at Kent State.

I had just been married two months before and had found my first job a few weeks later, with the welfare department -- not a great job, perhaps, but I was a man now, with responsibilities. Yet I had not given up my youthful hope of doing some good in the world. Wednesday afternoon about 4:30 I was on I-5 heading home; in those days you could still drive through Seattle on I-5.

But not that day. As I approached Downtown, I found traffic being shunted off the freeway. A demonstration the day before had taken over the freeway, and the radio had said another rally planned for today might do the same. Now, sure enough, a roadblock squeezed the interstate like a clamp.

My heart leapt. All day I had chafed at missing Tuesday's march (bloody responsibilities!). I yearned to join the students and put my body on the line to stop the madman Nixon.

Or at least watch.

I drove up Lakeview to a grassy slope above those bulkheads that keep Capitol Hill from sliding onto the freeway. Tuesday's children had marched peacefully from the University District into the city; now Wednesday's were said to be coming the other way.

Others gathered on the steep hillside as word spread of the demonstrators' approach. Most of us stood scattered across the slope, waiting, but a few leaned over the bulkhead and craned their necks to look down the vacant interstate into town.

I found a spot next to a woman wearing a batik dress and sandals, with white hair braided to her waist. She was old enough to be my grandmother.

"The killing has to stop," she said to me. "I mean in Asia and here and everywhere. If they need someone to kill, they can just kill me."

"Oh, I hope not," I said. I loved this woman instantly, a beautiful woman, a saint. But I made a mental note to drift away from her if trouble started.

While we waited, two busloads of Seattle's Finest arrived and parked along the shoulder below the bulkhead. Below us. The air across that hillside was suddenly charged with enough juice to power a Beverly Hills discotheque, and I began to sense that I might yet have some part in the unfolding of destiny.

Little did I know.

The officers were decked in riot gear, which had to be expected, of course: They were there to prevent a riot. Except that several of the officers were hanging out of the windows, beating the sides of their busses with yard-long clubs and whooping like born-again berserkers.

I began to wonder if I should have stopped. As the officers disembarked with their clubs and helmets and gas masks, it occurred to me that a certain innocence had been lost at Kent State -- and that maybe I should have gotten the hint. The white-haired woman moved away and down the hill a little for a better look.

Below me on the hillside a scraggly kid of 19 or 20 bent over and began picking up rocks off the ground. He dropped a handful into the pocket of his fatigue jacket, then bent over to pick up some more. Armed shocktroops were falling into formation below us, clamoring and lusting for blood, and this mastermind was getting ready to throw stones.

Before I could stop him, he pegged one of his rocks at the cops. My breath caught on something in my throat, and my life -- such as it was -- flashed before me. I thought of my wife. I thought of my job. I thought of the blood spilled in Ohio.

The rock fell short. In a brain-searing panic, I struggled to grasp what was unfolding before me. Watts and Newark and Detroit had burned and hundreds had died when the rock-throwing crazies and the bloodlusting cops had collided. Chicago had erupted into a riot fueled by the police, and now some of the Cossacks disgorging from these buses seemed to have exactly that in mind.

The kid was fishing in his pocket for more stones, so I knew I had only a split second in which to change the course of history -- and he was out of reach, so I knew I had only words with which to reach him. I pictured Seattle in flames around my bullet-riddled corpse, my darling wife kneeling over me in grief like that famous young woman in Ohio.

I reached down, as they say, and found the words I needed, words both wise and hip, both streetsmart and profound, and with all the conviction of my heart I hurled them down the hill at the scraggly youth:

"DON'T THROW ROCKS!"

For a moment the earth stood still. Physical reality suspended itself in time as will and destiny faced off in Seattle. Then began a slow waltz in which every dancer emerged from a blinding haze into a pure and lucid clarity. A cop turned slowly our way; for a moment I thought I could see the blood in his eye. The woman with the long white hair began to move, almost floating, down the hill. Dancers young and old waltzed with dreamlike grace on the lawn of that Wednesday evening hillside.

And at last the kid turned around.

His face was a misery of confusion. He looked past me up the hill, as if the voice had come from somewhere Up There, from Above. The kid was plainly wired, though certainly not from anything that expands the mind. A look of abject stupidity washed his features while now he struggled to understand.

"Don't throw rocks?" he said, still looking up the hill. He agonized a few moments more, a few lifetimes, perhaps, trying to discover the source of The Voice, then dropped his rocks.

And I began to breathe again.

The Cossacks stopped the marchers just below us and racked them against the wall. They got to crack a few heads and even launch a little gas, but they didn't get to fire a shot. The forces of justice had moved and the forces of order had responded -- but no one had thrown any more rocks.

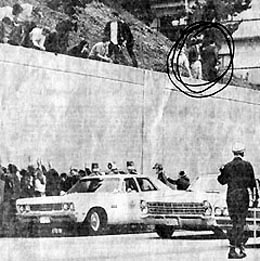

A photograph of the scene appeared the next day on page 3 of the Times. It showed the police, the students ... and me. I still have the photo. The cops have 16 or 18 of the demonstrators up against the bulkhead. I'm standing at the top of the wall, hands in my pockets, not looking at the arrests below me but off to my left in the direction from which apparently protesters were still coming. You can almost see me breathing again. You can't see the scraggly kid.

My boss spotted me in the photo and circled me in black ink, then clipped the photo and left it on my desk. I'm not sure he bought my explanation about saving the city; all the same, he let me keep my job.

But imagine if that kid had hit some cops. Think of the headlines: "Protest turns violent in Seattle." "Hundreds die in Washington State." "Northwest city burns." My life flashes before me when I think of it, even now.

I still wonder from time-to-time about the scraggly kid. I wonder if he made it through those terrible, exciting times, and all the terrible times since. That poor, dumb kid. I wonder if he knows he damn near got us killed. Or that the short guy behind him saved Seattle.