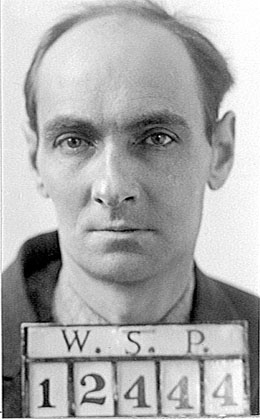

On May 12, 1938, Decasto Eugene Mayer (1894-1938) and Mary Eleanor Smith (1866-1966) are charged with the murder in 1928 of James Eugene Bassett (ca. 1894-1928). On September 5, 1928, Bassett, age 34, had mysteriously disappeared while on a trip from Bremerton to Seattle to sell his new 1929 Chrysler 75 roadster to a man calling himself "Mr. Clark." Eight days later, Decasto Earl Mayer, age 34, and Mary Eleanor Smith, age 62, were arrested in Oakland, California, in possession of Bassett's automobile and personal effects. Seattle police were unable to find Bassett's body and the prisoners stood mute. With no evidence of a victim, Mayer and Smith were convicted of grand larceny in King County and sent to the Washington State Penitentiary, Smith for 10 years and Mayer for life as a habitual criminal. The search for Bassett continued in earnest for many months, but without success. Ten years later, in 1938, just prior to being released from prison, Smith confesses that she and Mayer murdered Bassett for his car, dismembered the body and buried the pieces in various locations. Although Bassett's body is still missing, King County Prosecutor B. Gray Warner charges the pair with premeditated murder and brings the case to trial. During the final days of trial, Mayer will cheat the hangman by committing suicide in his jail cell. Smith will plead guilty to Bassett's homicide and be sentenced to life imprisonment. The disappearance of James E. Bassett is one of the most sensational and bizarre murder cases in Pacific Northwest history.

Murder Detailed

In 1938, Decasto Earl Mayer and Mary Eleanor Smith were both serving sentences at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla for grand larceny committed in 1928. Mayer had been sentenced to life imprisonment, having been convicted of being a habitual criminal, and Smith had received a sentence of eight-and-a-half years. But the fate of James Eugene "Gene" Bassett, whose automobile and personal effects they had stolen, was the big question. On Wednesday, May 4, 1938, five days before Smith's release from custody, Warden James M. McCauley (1890-1940) announced that she had signed a statement confessing the details of Bassett's murder.

Smith's cell mate and confidante was Margaret Helen Fawcett, age 55, a notorious confidence artist serving 15 years for grand larceny. In 1937, Smith told Fawcett the details of the Bassett homicide as well as details of three other murders she and Mayer had committed. Sensing an opportunity for clemency or a pardon, Fawcett went to the prison matron, Hope Nixdorff, and repeated Smith's confession. Nixdorff suggested Fawcett get Smith to write the details in personal letters and, because all inmate mail was screened, offer to have the letters smuggled out through the prison underground. Smith wrote several letters, which were turned over Nixdorff.

Later, Fawcett was asked to introduce Washington State Patrol Sergeant Joseph McCauley as a "clergyman," in an effort to gain Mary Smith's confidence and possibly learn where Bassett's body had been buried. "Father" McCauley and Smith engaged in long conversations during which she made numerous admissions, but provided no useful information about Bassett's location. Months later, McCauley was called as a trial witness, but the court ruled that the priest-penitent privilege had been violated and his testimony was excluded.

Finally, one week before Mary Eleanor Smith was due to be released, Warden McCauley confronted her with a four-page letter containing a complete account of Bassett's murder and identifying Mayer as the killer. Smith admitted the document was in her handwriting and facts contained therein were true. The following day, she sent Warden McCauley a letter confirming her oral admissions, signed a formal confession repeating the details contained in the letter and agreed to help hunt for the body.

Telling the Truth

The following is the statement of Mary Eleanor Smith signed on May 4, 1938:

"I am going to tell you the truth. The automobile was advertised for sale by Eugene Bassett who was on his way from Maryland to take a position in Manila, P.I. He was visiting at his sister's home on the Navy Yards at Bremerton near Seattle. Her husband was Commodore Winters.

"Earl answered the ad and went over to see Bassett at his sister's home. It was on September 5, 1928, but being Labor Day, did not transact business until the next day. It was a most beautiful car and he wanted it as he had two very good positions offered by real estate men, one by Charles Hallman.

"He came home and told me this. As I was getting my divorce from Smith at that time, I had not yet seen the car, so he told me he was going to bring Bassett to our house the next day and do away with him.

"We took the Dr. J. W. Clark house for this kind of purpose, as we knew whatever car we got we would have to do away with the owner, and this was an ideal spot for the purpose.

"Earl went and got him on the morning of the sixth, took him to a notary public office for the purpose of making believe he wanted a bill of sale. While there, Earl said we could not close the deal until he spoke to his mother and she would have to write out the check. We brought him home and I was sitting on the couch where I had a rod of iron hidden in a quilt in case of struggle.

"We also had the phone removed; every precaution was taken. When we said we would pay in check, Bassett consented and said it was O.K. with him. I got up from the couch and set down at the writing desk. Earl gave me a hint to leave the room. Bassett sat in the chair in front of the fireplace as I stepped into the kitchen. Earl stepped up behind Bassett and handed him a blank telegram and said, 'I am going to have your car and I won't pay for it. You write this telegram as I write it.' Bassett refused, but Earl said you write it or I'll kill you. So he wrote as follows: 'Mrs. Commodore Winters, Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wn. I have sold my car, met a friend and am going to Vancouver for 3 days. Signed Gene.'

"As Earl took the telegram, he picked up a hammer and hit Bassett on the head. I heard his body fall and went in and he was gurgling. I stepped out and Earl gave one blow and it was all over. We dragged the body into the bathroom, undressed it and put the body in the bathtub, where he dissected it at once.

"I cleared the mess and burned the clothes and the scalp also was burned. Earl was so sick and weak, I gave him eggnog to keep him up. At night we took the pieces of the body, minus the head and hands, and drove way out to a big patch of woods somewhere between Cathcart and Bothell and put them under some brush clump.

"The next morning we took the hands and head miles away to another patch of woods and buried the hands on one side of the road at a distance and the head on the other side into an old abandoned woodchuck hole at arm's length. This is all about the Bassett Case" (The Seattle Times).

Denying and Confessing

On Thursday morning, May 5, Warden McCauley brought Smith and Mayer together for a face-to-face confrontation in the presence of Chief of Detectives Ernest W. Yoris, Seattle Police Department, and King County Deputy Prosecutor John M. Schermer. After hearing Smith recount the details of Bassett's murder, Mayer denied the charges and said she was insane. That afternoon, Yoris and Schermer drove Smith to Seattle to resume the hunt for Bassett's body.

Later, Smith's confession was read to Mayer again and he admitted it was substantially correct. Although Mayer refused to make a written confession, on Saturday, May 7, he voluntarily signed the following statement: "After discussion with Warden McCauley and after seriously considering the situation, I have decided to plead guilty to the murder of Bassett. I will disclose the details to the proper authorities" (The Seattle Times). Inadvertently, Mayer had adopted Smith's confession as his own and, although he later repudiated it, the document became admissible as evidence against him in trial.

Preparing for Trial

At Warden McCauley's request, Governor Clarence D. Martin (1884-1955) granted a special leave of absence for Mayer so he could be brought to King County and charged with first-degree murder along with Smith. On Monday morning, May 9, Mayer left the penitentiary for the first time in eight years in the custody of Chief Yoris and King County Prosecutor B. Gray Warner for the 290-mile drive to Seattle. Although Mary Smith was scheduled for release on Monday, she was held in the Seattle City Jail as a material witness.

On Thursday, May 12, Prosecutor Warner filed an information in King County Superior Court charging Mayer and Smith with first-degree murder. Arrest warrants were issued and served on the two prisoners being held in the Seattle City Jail. On Tuesday, May 24, Mayer and Smith were arraigned before Judge Robert M. Jones, who appointed Seattle Attorneys Milton Heiman and Warren Hardy as defense counsel. Judge Jones ruled that Mayer would remain in Seattle pending trial and both prisoners be transferred to the King County Jail. Judge Jones also issued a restraining order prohibiting the police from the use of "truth serum" (scopolamine) and "lie detectors" (polygraph) to question Mayer and Smith, or forcing them to submit to further questioning. Prosecutor Warner said the state was seeking the death penalty, had enough evidence to convict and had no need to question the defendants further.

On Tuesday, May 31, Mayer pleaded not guilty to the charge of first-degree murder, and Attorney Hardy entered a special plea of insanity on behalf of Smith. Prosecutor Warner pointed out that Smith had been examined by Dr. Edward D. Hoedemaker, a state psychiatrist, who declared she was sane. Judge Jones accepted both defendant's pleas and said any future motion for a sanity hearing would be given due consideration.

The Search for Bassett's Body

In 1928, police had conducted an exhaustive search of the residence, always referred to as the "little brown house," located in North Seattle on N 185th Street, between Greenwood Avenue N and Fremont Avenue N, where it was suspected Bassett had been murdered. They found a set Maryland license plates, registered to Bassett's automobile, hidden on top of a beam in the basement, and remnants of burnt clothing and buttons among the ashes in the stove and fireplace, but no trace of Bassett's body. This evidence would prove extremely valuable in the upcoming trial to help corroborate Smith's confession.

A team of investigators revisited the "little brown house" and surrounding property to search for evidence, which may have been overlooked, but found nothing new. Chief Yoris took Smith to the "little brown house" where she voluntarily re-enacted the crime and then made several apparent attempts to find Bassett's body, but without success. Luke S. May (1892-1965), a renowned criminologist, was engaged to search for traces of blood in the cracks of the floorboard. Unfortunately, a fire had destroyed most of the house in 1932 and all the flooring, except for a portion in the living room, had been replaced. May took numerous samples, but subsequent analysis for blood proved inconclusive.

Every effort had been made to find Bassett's body and now it was highly unlikely it would ever be found. Even without the corpus delicti (the substantial and fundamental fact necessary to prove a crime has been committed, such as a victim) to prove murder, however, the state was in a far better position than it had been 10 years earlier. The prosecution had Smith's detailed confession, adopted by Mayer, supported by enough corroborating and circumstantial evidence to support a verdict of guilty. Prosecutors felt that the risk of a directed verdict of acquittal was no longer a sufficient reason to delay the trial date. Investigators had already begun the difficult task of locating and re-interviewing the witnesses who had testified in the grand larceny trials in 1928.

The Insanity Option

In July, Attorney Hardy announced that Smith intended to withdraw her plea of insanity. Prosecutor Warner had a decision to make. It was evident Hardy intended to argue at trial that Smith was temporarily insane at the time of her confession to the Bassett murder, but now was sane. Hardy intended to show that Smith's cell mate, Margaret Fawcett, caused her temporary insanity and manipulated her into confessing. He maintained Fawcett was seeking clemency or a pardon for her part in solving the Bassett case.

On September 23, 1938 Prosecutor Warner requested Superior Court Judge Howard M. Findley appoint a commission of psychiatrists to determine the sanity of Mary Eleanor Smith. Warner surmised if Smith were declared insane, her confession and testimony against Mayer would be worthless. Instead of hazarding an expensive trial, Smith would be committed to a state mental hospital and Mayer would be returned to the Washington State Penitentiary to continue serving his life sentence for being a habitual criminal. Other than the satisfaction of bringing two killers to justice, Warner had little to lose.

On September 28, Judge Findley appointed three psychiatrists to the sanity commission: Dr. Donald A. Nicholson, Dr. George E. Price, and Dr. Edward C. Ruge. On Monday, October 3, Dr. Nicholson, chairman of the examining board, declared Smith was not only sane now but had also been sane when she wrote the letter confessing she and Mayer killed Bassett. The following day, Judge Findley scheduled the trial to commence on November 28 before Judge Chester A. Batchelor

On Trial for Murder

Trial began on Monday, November 28, 1938, with jury selection, which took five full days to complete. The 10-year-old mystery of Bassett's disappearance and probable murder had become one of the most sensational criminal cases in the history of the Pacific Northwest. And it was for this reason both sides encountered difficulties finding jurors without preconceived ideas about the guilt or innocence of the defendants. Most of the prospective jurors questioned, however, had no objection to imposing the death penalty on a 73-year-old mother and her alleged son for such a cold-blooded murder.

Finally, on Friday, December 2, after examining 91 veniremen, a jury of four women and eight men, plus two alternates, was impaneled. On Saturday morning, the jury was sworn and Prosecuting Attorney Warner presented a two-hour opening statement in which he described the details of Bassett's homicide. He conceded that the state did not have an actual body in this case, but would prove, through circumstantial evidence and corroborated confessions the defendants killed Bassett and dismembered and disposed of his body in order to gain possession of his automobile. Warner concluded by demanding the death penalty for both defendants.

In his opening argument, Attorney Heiman stated briefly the defense planned to call no witnesses because the state couldn't prove a homicide had taken place, and therefore had no case. Further, it was the contention of the defense that Bassett might still be alive.

Over the next 12 days of trial, the prosecution called 75 witnesses to the stand, most of whom had testified against Mayer and Smith in two previous trials for grand larceny. Early in the proceeding, Judge Batchelor ruled the state was not required to produce Bassett's body in evidence, although it must prove his death.

Prosecutor Warner had four witnesses who proved vital in substantiating the corpus delicti (the body of the crime) of the state's case. Warden McCauley and Margaret Fawcett had been instrumental in obtaining legally admissible confessions from the defendants regarding Bassett's murder. And there were two surprise witnesses who provided evidence of a body.

New Evidence

At 9:40 p.m. Wednesday, September 5, 1928, Constatin O. Schmidt and his son, Julius, were driving along the Bothell-Everett Highway (State Highway 527) in Snohomish County when a bright-blue Chrysler roadster passed them at high speed. When the driver attempted to negotiate the Cathcart turnoff, he skidded off the dirt road into a ditch. The Schmidts noticed the roadster had Maryland license plates and stopped to render assistance. Two full gunnysacks, covered with what appeared to be blood, were sitting in the rumble seat and a shovel was tied to the side of the vehicle. The two occupants, later identified as Mayer and Smith, ignored the Schmidts, and sped off toward the heavily wooded Cathcart area. After a short distance, the driver stopped and turned off the headlights. Perplexed, Schmidt recorded the car's license plate number on the dashboard of his car. (Although the prosecution was aware of Schmidt's story in 1928, it wasn't considered relevant to the grand larceny charges and he hadn't been subpoenaed to testify.)

During cross-examination, Defense Attorney Heiman asked Schmidt the number of the license plate. Reaching into the breast pocket of his coat, he pulled out an old piece of paper and read the number for the jury: Maryland 139-212. Both sides, apparently unaware of Schmidt's note, rushed to confirm the number. It had been issued to Bassett's 1929 Chrysler 75 roadster in July 1928. When asked, Schmidt explained he copied the number from his dashboard onto a piece of paper when he got home in case the tourists from Maryland got in trouble. He never told anyone about the note because no one ever asked. The next witness to testify was Julius Schmidt, who confirmed his father's story

During an abbreviated court session on Saturday, December 10, 1938, the state rested it case. After the jury was sequestered, the defense immediately filed motions for directed verdicts of acquittal, challenging sufficiency of evidence to support a verdict and contending the corpus delicti (the body of the crime) had not been established. Attorney Heiman argued the confession was not sufficient to establish the crime and the testimonial evidence, establishing Bassett's body, was questionable at best. At the conclusion of Heiman's statement, Judge Batchelor continued further arguments on the motion until Monday morning.

Mayer's Suicide

On Sunday, December 11, however, Mayer committed suicide while in solitary confinement at the King County Jail. His body was discovered at about 3:05 p.m. by jailer John A. Anderson making a routine check before sending in dinner. Dr. Charles C. Tiffin, jail physician, was summoned and pronounced him dead. King County Coroner Otto H. Mittelstadt said Mayer had been dead for less than one hour before his body was discovered.

According to Sheriff William B. Severyns (1887-1944), Mayer used his leather belt in a unsuccessful attempt to hang himself from the upper bunk bed. The belt broke and he dropped to the cement floor, lacerating his forehead. Instead, Mayer strangled on wet paper towels he crammed down his throat and wads of toilet paper he stuffed in his nostrils, secured with two makeshift gags. He also tied his hands together with strips torn from his shirt, making sure he couldn't free himself.

In a note he left for Mary Eleanor Smith, his alleged mother, Mayer wrote that he was tired of life and his death would make everything easier for her in the future. But Prosecutor Warner had a different opinion. "The strength of the state case became apparent to Mayer last week. He feared he would hang and took the easy way out" (The Seattle Times).

Despite Mayer's suicide, the trial resumed on Monday morning, December 12, with both the prosecution and defense arguing Mary Smith's motion for a directed verdict of acquittal. Meanwhile, the jury remained sequestered in the dormitory at the King County Courthouse. After court was adjourned, Judge Batchelor thoroughly researched the corpus delicti issue and wrote a nine-page opinion regarding the proof-of-death question in the Bassett trial.

At Mary Eleanor Smith's request, a private funeral service was conducted for Mayer at 7:00 p.m. on Monday, December 12, in the reception room of the Coroner's office in the King County Courthouse. She was brought down from her jail cell in the women's quarters under the supervision of Jean Jackson, jail matron, to attend the simple service. The only flowers on Mayer's coffin was a spray of small yellow chrysanthemums, provided by Coroner Mittelstadt. The following day, Mayer's body was cremated, as requested in his suicide note.

Changing the Plea

On Tuesday morning, December 13, Judge Batchelor denied the defense's motion, stating the prosecution had produced sufficient evidence to warrant sending the case to the jury. There followed a meeting in chambers during which Judge Batchelor informed defense counsel the report from the sanity commission, finding Smith sane, would be introduced into evidence. After a brief consultation with the defendant, Smith, Attorney Hardy told Judge Batchelor, "my client wishes to withdraw her plea of not guilty by reason of insanity and substitute a plea of guilty to murder in the first degree" (The Seattle Times).

Court was reconvened and Mary Smith was led to the bar to make her formal plea. Judge Batchelor accepted her guilty plea and had the bailiff escort the jury into the courtroom. The jurors, sequestered since Saturday morning while the attorneys were arguing motions, were informed defendant that Mayer had died on Sunday, but didn't reveal the circumstance, and Smith had changed her plea to guilty of first-degree murder. The judge announced the trial would now proceed and asked if there were any further witnesses.

While Mary Eleanor Smith sat hunched in her chair at the defense table, snuffling into her handkerchief, Prosecutor Warner recalled Mrs. Marion F. Bassett, the victim's mother, to the witness stand. He asked Mrs. Bassett if, in view of the circumstances, she wished the state to demand the death penalty for defendant Smith. "No," she replied. "I shall be satisfied and content if she remains in prison" (The Seattle Times). The defense declined to cross-examine the witness and she was dismissed from the stand.

In his brief closing argument, Prosecutor Warner told the jury he wished to withdraw his demand for the death penalty, opting instead for life imprisonment. Both defense attorneys followed with brief pleas to follow the recommendation of Mrs. Bassett and Prosecutor Warner. Judge Batchelor then read a hastily revised set of instructions to the jurors, explaining their only duty now was to decide between life imprisonment and death for defendant Smith.

The jury retired to deliberate at 11:26 a.m. and reached its verdict against the death penalty 19 minutes later. After a brief recess, Judge Batchelor, pronounced defendant Smith be confined in the Washington State Penitentiary for the rest of her natural life. The homicide of James Eugene Bassett had been legally solved and the case finally closed after 10 long years. On Wednesday morning, December 14, Mary Smith, Margaret Fawcett, and three other female prisoners left the King County Jail on a state penitentiary bus bound for Walla Walla.

Old Age

On March 11, 1953, Dr. Henry Ness, chairman of the Washington State Board of Prison Terms and Paroles, announced that Mary Eleanor Smith, now age 87, would be paroled from the Washington State Penitentiary and confined in a nursing home in the Walla Walla area. Dr. Ness said the state parole board took the action because Smith was in poor health and the woman's prison was not equipped or staffed to handle such prisoners.

Although nearly blind and unable to walk or care for herself, she managed to hang on for another 13 years at taxpayer expense. Smith died at age 100 in Spokane on Friday, March 2, 1966. Her body was sent back to Walla Walla and, after a brief graveside service, buried at the Blue Mountain Memorial Gardens. Her death was the final chapter in one of the Pacific Northwest's most sensational and bizarre murder cases.