The King County Library System (KCLS) operates libraries in communities throughout King County (outside Seattle), a variety of mobile outreach services, a library within the King County Youth Services Center, a shipping-and-handling facility, and an administrative service center. It is among the busiest library systems in the United States. Established in 1942 and 1943 by King County voters and the Board of County Commissioners as the King County Rural Library District, the system was initially composed of small rural libraries run largely by volunteers. Since its inception, KCLS has been funded by property taxes, and as the county population has increased so have these tax revenues. Successful bond issues, individual community decisions to annex to the library system, and a massive library-construction effort in the 1990s resulted in a growing library system serving its patrons in continually evolving ways, upholding its stated mission of providing free, open, and equal access to ideas and information to all members of the community. Part 1 of this two-part history tells the story of KCLS from its establishment through the end of the twentieth century.

Getting Started

The King County Board of Commissioners established the King County Rural Library District on January 4, 1943, as directed by a majority vote of rural residents of the county on November 3, 1942. On January 11, 1943, as required by state law, the Board of Commissioners appointed a board of library trustees. Judson T. Jennings (1873-1948) chaired the five-member library board. Recently retired from a long tenure as head librarian at the Seattle Public Library, Jennings brought a wealth of experience to the position.

On June 14, 1943, the King County Rural Library District and the Seattle Public Library entered into a contract that allowed all county library patrons to utilize all services of all branches of the Seattle Public Library, including interlibrary loans. The contract went into effect on September 1, 1943, giving residents of rural King County the immediate opportunity to access the collection of what was at the time the largest public library in the Pacific Northwest.

King County library staff, meanwhile, began ordering new books that would form the county's own collection. Doris Hopkins, a Seattle Public Library staff member, was given six months leave of absence to help King County select books to order.

Staff, Space, Services

Ella McDowell, a Seattle Public Library reference librarian for the previous 12 years, was the King County Rural Library District's first director. McDowell served as director until October 1951, when she was succeeded by Dorothy Alvord (1895-1982), who had been associate director since 1948. The library district first rented central-services office space at 906 and 908 4th Avenue in downtown Seattle, then purchased a building at 1100 E Union Street in 1952. This building was not a public outlet, but served as a clearinghouse for the library district's bookmobile and branch-library services. A new Central Services facility at 300 8th Avenue North in Seattle was dedicated on October 1, 1972. In 2000, central services moved to a new facility at in Issaquah.

Dorothy Alvord retired in 1962. Her former assistant director, Phillip List, served as acting director until early 1963, when Herbert F. Mutschler (1919-2001) assumed directorship. Mutschler guided the organization until June 1989, when he was succeeded by William Ptacek (b. 1951).

From the time library services became established, services for children such as juvenile books, summer reading clubs, story hours, and book talks in schools, were a key aspect of the work. By the end of King County Library's first full year of operations, 45 percent of all books circulated were borrowed by or for children.

Earliest Libraries

Branches came into the rural library district by several methods: an existing independent library (usually staffed solely by volunteers) in an unincorporated community could affiliate with the district; incorporated communities with existing libraries could contract for services or organize and fund new facilities; or residents living in unincorporated communities could band together to establish a new facility, and then affiliate. Services to unincorporated communities operated without formal contracts, whereas incorporated municipalities contracted formally with the library district.

Each library had a sponsoring group. In incorporated contracting towns, this group consisted of five library board members appointed by the community's mayor with the consent of the town council. In unincorporated communities, the sponsoring group was sometimes a PTA; a community service organization; or a library guild, association, or Friends group.

On December 27, 1943, Boulevard Park became the first community to ask the King County Rural Library District for service. As existing libraries such as that in Boulevard Park (where the library had been run by the Wednesday Study Club) joined King County Library, their existing books became part of the larger collection. Boulevard Park brought its 460 volumes.

On January 3, 1944, Richmond Beach Library became the second library to join, bringing 1,296 volumes to the county collection. During that same year, Snoqualmie Falls joined on February 1, 1944, Lake City joined on February 4, Bellevue on February 5, Burien on February 18, Vashon Island on March 6, Fall City on March 15, Des Moines on March 20, North End (outside the then Seattle city limits) on April 8, Brook Lake on May 18, Stewart Heights on May 19, Renton Highlands on June 3, Steel Lake on June 23, Burton on July 29, Richmond Highlands on July 31, Lakewood on November 6, Cedar Vale on November 10, and Preston on November 15. Mercer Island, Foster, Skykomish, Woodinville, White Center Heights, and Duwamish (which developed from a bookmobile stop site) joined during the first half of 1945. Skykomish was the first incorporated city to contract with King County Rural Library District. In the latter half of the year, Black Diamond, Lester, and Auburn City swelled the King County Library ranks.

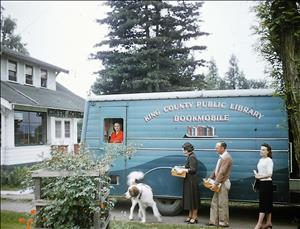

Belinda the Bookmobile

During the early years, wartime shortages made buying a bookmobile to serve communities too small for their own library next to impossible, but King County Library was able to obtain one that had belonged to the Seattle Public Library. The mobile unit, which had been used as part of the W.P.A. (Works Progress/Projects Administration) library demonstration project, was overhauled and made its first run on July 13, 1944. By October the mobile unit was servicing 10 routes five days a week, returning to each of its 74 stops twice per month. The vehicle, beloved from its first run, was nicknamed Belinda.

Some communities that received bookmobile services eventually acquired physical facilities and established libraries, contracting with the library district for continued services -- another indication the bookmobiles helped establish and encourage the habit of library use.

Books by Mail

From its inception until 1995, King County Library offered library book delivery via mail. This service was very convenient for elderly patrons and those with limited mobility or problems physically accessing libraries. The library paid for books to reach the patrons via parcel post, and the patron was responsible for paying return postage. The librarian in charge of this service filled specific requests, or chose books for the patrons according to her understanding of each patron's reading taste.

As recounted in the 1945 Annual Report, "the rural delivery postmen become helpers in this very personal service. One woman reports, 'My post box is down a long lane, so when there are books for me the driver honks loudly. He can't wait for me to come down so he carries them on with him, but I have had the signal and know I should meet him the next day'" (p. 4).

Steady Growth in the 1940s

Service grew steadily during King County Library's early years as new libraries joined the organization. One unique aspect of the county library system was described in the 1945 annual report:

"Instead of having permanent collections in each of the small libraries, all communities have a continuing flow of fresh titles, and 'read-out' books are withdrawn to be sent to a different branch. Fifteen thousand six hundred forty six titles changed location in this way" (p. 1).

Issaquah, Snoqualmie, North Bend, Tolt-Carnation, and Bothell (all incorporated cities) signed the services contract in 1946. New libraries in unincorporated communities that opened that year included Orilla, Redondo, South Park Courts, Algona, and White Center. The year 1947 saw the addition of libraries in Redmond and Pacific (both contracting incorporated cities) and Maple Valley. Houghton came on board in 1948. New libraries joined more slowly thereafter, and some libraries left the county system when areas in which they were sited were annexed by non-affiliated incorporated cities.

King County Library also began establishing so-called library stations (meant to serve a limited number of people without the formality of regular service hours) at convalescent homes and at the Riverton Heights and Laurel Beach tuberculosis sanatoriums. Books serving infectious populations were fumigated before being returned to general circulation.

As the 1940s drew to a close, space was the biggest issue facing King County libraries. Returning service members, expanding families, and increasing population meant increased circulation. Some libraries were able to purchase government surplus buildings or construction materials, adding an annex here and a few shelves there. Vashon, which already had a library building in the planning stages when the community joined King County Rural Library District in 1944, opened that new building (a memorial to Vashon Island residents who had lost their lives in World War II) in 1946.

Celeste the Bookmobile

A second bookmobile, on order for several years but never delivered due to wartime restrictions, was finally received and put into service in 1947, generating much publicity and an immediate jump in circulation. The vehicle, known fondly as Celeste, was one of eight built for Washington libraries by Pacific Body Builders of Portland and Vancouver Chevrolet of Vancouver, Washington.

"Celeste is well-arranged for taking care of a large number of people in a short time," stated the 1947 Annual Report on Book Mobiles. "Except for the blunt rear, it is a good-looking unit, business-like and pleasing to the eye" (p. 1). Operational quirks and flaws would make Celeste a challenging addition to King County Library throughout her years of service. "Celeste's light generator and heater are both nightmares," the 1947 report admits.

From Punch-Cards to Electronics

Responding to the great difficulty of keeping all libraries apprised of the rapidly shifting, ever-increasing collection, in 1950 King County professional librarians requested, and the Library Board approved, a state-of-the-art cataloging system developed by IBM. Organizing for and implementing the new equipment took several years, and King County Rural Library District was among the first libraries in the country to utilize this system.

Computerizing the catalog 1950s-style, as explained in the 1950 Annual Report, required:

"The selection of 189 simplified subject headings to be used for the book collections in the small branch libraries. The making of an index in pamphlet form, called 'The Key' which refers to these 189 subject headings from the many subjects which might be requested at the branch libraries. Punching a master title card for each title owned. Reproducing the punched card for each copy of every title. Sorting all of these punched cards by alphabetical and numerical classification into one file. Selecting the cards for the books which at that moment were in each branch collection (discarding the old file in each case). Printing the new branch catalogs from these punched cards" (p. 2).

This system pre-dated the first electronic computer developed by IBM and first sold in 1953, as well as photocopy machines, which did not become common office features until the mid-1970s.

The 1958-1959 Annual Report praised the system as "throw-away catalogs for changing book collections," describing the catalogs as "mounted in book form in five parts. They may be duplicated by carbon or easily re-run if more copies are needed in the branch. They are unmounted and thrown away every two months when the new printing arrives" (p. 6). These catalogs were used only in the branches -- the central service center still maintained a complete card catalog.

In 1972, King County Library began using Xerox computer-produced catalogs. This was replaced in 1977-1978 by a microfiche catalog system. The library catalog was computerized and made available online in 1991.

Funding Issues

During the first two decades of its existence, the King County Rural Library District utilized the vast majority of its non-salary resources to acquire new books and build its collection. With no funds allocated to building acquisition or maintenance, those duties fell to the individual communities where each library was located. Bake sales, book sales, dances, direct solicitation, and various other methods were used to raise funds.

As the county grew, and with it, assessed property evaluation, the King County Rural Library District was able to assume some of the expense of maintaining the library buildings. By the late 1960s, the district was in the process of acquiring the buildings that libraries in unincorporated communities occupied.

In 1961, a new state law authorized local improvement districts for library construction within rural county library districts. King County, with 40 active libraries, was the first county to try to put this law -- which could have greatly accelerated construction of new facilities -- into effect, but the law was challenged and eventually struck down by the state supreme court. Grounds for this decision were that "libraries are not constructed primarily to enhance the value of the real estate surrounding them. For this reason, their construction cannot constitutionally be financed by assessing the cost thereof against the adjacent real estate" (Dobb, 48).

The 1960s -- A Chance to Build

In 1964, the Federal Library Service and Construction Act of 1957 was amended to extend library aid to non-rural areas. This made local library projects eligible for federal matching funds to acquire sites, construct new libraries or expand existing ones, and purchase additional equipment, as long as projects conformed to state requirements for library construction and that they served areas lacking existing library services.

By 1966, the library district had grown from one library with circulation of 1,983 items in a 2,846-volume collection, to 40 libraries and three bookmobiles, annual circulation of 2,280,248, and a collection of more than 550,000 volumes. Increased service garnered increased public support, and in 1966, county voters approved a $6 million bond issue to build or improve 20 library facilities. The Library Location Plan, published in July 1965, served to guide placement of the new libraries, and reorientation of some existing libraries. By 1977, 24 projects had actually been completed.

The 1970s -- Rural No More

King County Rural Library District funding (as of 1977) came from a tax levy of not more than $.50 per thousand dollars of assessed property value, with a cap prohibiting collection of more than 106 percent of the highest amount collected in the previous three years. The library district was also able issue general obligation bonds with voter approval, with the proceeds used for capital improvement projects.

By the late 1970s, the words "rural library district" were no longer commonly used, although that wording remains part of the organization's legal title. In 1978, which marked the district's 35th year of service, the annual report re-christened the organization the King County Library System.

In response to the troubling issue of stolen books (by the late 1970s some $17,500 worth of books were disappearing annually), KCLS began installing materials-security systems. These systems ensured that books were checked out to a specific patron before being carried from the building.

Assessing Services

In 1977, Seattle and King County produced a study that attempted to untangle the issue of who, exactly, used which library system. Due to budget problems, in 1977 KCLS did not pay Seattle Public Library the $50,000 annual fee for services -- the report calls it "a symbolic payment towards the cost of services to non-residents by Seattle Public Library" (p. 2).

Seattle wanted to recover full cost for serving county residents outside Seattle city limits. Both KCLS and Seattle Public Library were under the funding gun. A comprehensive management analysis of Seattle Public Library performed in 1974 had established the fact that $748,948 of services were being provided annually by Seattle Public Library to non-residents living in King County. King County had no real way to quantify how many Seattle residents used KCLS libraries: At the time, KCLS did not issue library cards or register library users.

The 1977 report estimated (based on various past surveys) that Seattle residents who worked or lived closer to one of the KCLS libraries than they did to a branch of the Seattle Public Library were likely to use the KCLS library -- proximity winning out over actual residency. Surveys showed that library users did not distinguish between library service boundaries -- they used "their" library -- the closest to their home or workplace. When nonresidents used Seattle Public Library, surveys found, they did less checking out of materials and more in-library research, utilizing the services of librarians to a -- presumably -- costly tune.

Merge with Seattle Public Library?

The question of consolidating the two systems was raised periodically, but the many obstacles to this solution included the fact that the city of Seattle funded its libraries directly, whereas King County had no obligation for general library services -- KCLS was a separate legal entity.

This meant that the funding sources of the two entities were incompatible: the Seattle Public Library was (and is) funded from the municipal budget, and KCLS was (and is) funded primarily by property taxes. Another issue was whether King County would begin to provide funds to KCLS -- at an estimated $10,000 rate at the time.

Serving King County

State law only required counties to provide a room suitable for a law library, with the operational budget for such a library funded by court filing fees. Outside of meeting that requirement, library service varied greatly from county to county. As of 1977, the report noted, 12 of Washington's 39 counties had no library district and 52 municipalities provided no library services of any kind to their citizens.

KCLS was at the time absorbing approximately 20 percent of the administrative costs of many of the services it provided under contract to the county, including those at the King County Jail, King County Youth Services, and Cedar Hills Treatment Facility.

In 1977 when the report was issued, five library systems were in place within King County: the municipal systems of Seattle, Enumclaw, Auburn, and Renton, and KCLS.

New Library Technology

King County Library continued past policy of quickly adopting beneficial new technology, installing a million-dollar Universal Library Systems (ULISYS) in 1981-1982. This system kept track of all circulation, improved the process of reserving items, and expedited the process of issuing overdue notices. This system necessitated signing borrowers up for library cards with unique barcode identifiers -- the first time library cards had been issued system-wide.

The library also installed two state-of-the-art Apple II Plus microcomputers, color monitors, disc drives, and printers, one in Lake Hills and one in White Center. "From the demonstrated success of this pilot project, KCLS officials concluded that personal computers have a bright future at KCLS," the 1982 Annual Report stated (p. 1). The library began circulating VHS tapes and using portable Extend-A-Phones (an early cordless phone) to free staffers from their desks.

Expanding and Funding

Between 1980 and 1987, 63 percent of King County’s population increase occurred in unincorporated areas. This meant increased revenue for KCLS, and also increased use. In 1986, a record 7,853,219 items were circulated -- a 79 percent increase since 1982. The library board began a major planning effort to respond to this greatly increased demand, voting unanimously to approve a $67 million bond issue to be placed on the September 20, 1988 ballot.

Planning and/or construction for new buildings for the Des Moines Library, Kent Library, and Bellevue Library, and expansions of the Lake Hills Library and Bothell Library were already underway, and were not impacted by the bond issue. The bond issue would fund planning and construction of libraries in Federal Way, Woodinville, East Kent, Pine Lake, Shoreline, Upper Snoqualmie, Burien, Newport Way, Redmond, Maple Valley, Carnation/Duvall, and a library service center. New construction and/or expansions for Juanita, Richmond Beach, Bellevue/Redmond, and Algona/Pacific were also under board consideration.

Changes in the 1990s

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, a number of libraries in incorporated cities that had been affiliated with KCLS via contract voted to fully annex to the King County Library System, as did other communities that had not previously been affiliated. For library patrons, this change was fairly invisible. The change was beneficial for KCLS, increasing operational standardization.

In 1991, the system gained an important resource: the King County Library System Foundation. The foundation began providing supplemental funding for special programs, activities, and collections. Many libraries also benefited from active Friends of the Library organizations. The library catalog was computerized and went online in 1991. In 1994, King County Library offered card holders the ability to connect with the internet from libraries or from home using dial-up modems. In 1995, King County Libraries replaced its longstanding Books by Mail service with Slick (Speedy Library Info Checkout), an interlibrary delivery system for reserved titles.

Operating under the so-called Year 2000 Plan, a growth strategy that took into account King County's projected 350,000 person population increase by that year, KCLS planned for tremendous growth and rapid expansion of both services and facilities. Computerized databases such as InfoTrac and Westlaw (a computer-assisted legal research system) were introduced. Six libraries (Lake Hills, Burien, Redmond, Maple Valley, Newport Way, and Carnation) were expanded. Eight buildings (Kent, Black Diamond, Mercer Island, Bellevue, Shoreline, Richmond Beach, Upper Snoqualmie, and Bothell) were replaced. Seven new libraries (Federal Way, Woodinville, Soos Creek, Pine Lake, East Kent, Federal Way North, and Algona-Pacific) and a service center were built. Funding for these projects came either from their specific community or jointly from the community and King County Library System via the 1988 bond issue funds, or from the bond issue solely.

As the twentieth century came to a close, KCLS had grown from its modest rural roots into one of King County's largest and most popular civic institutions. It was positioned to grow even further, and to become the busiest library system in the nation for a time, and an influential model for other library systems.

To go to Part 2, click "Next Feature"