On June 16, 1918, several hundred South Bend and Raymond residents travel to the Tokeland area and gather 775 sacks of sphagnum moss for bandages to be sent to the front lines of World War I. The effort is organized by local Red Cross volunteers to aid Allied armies facing a shortage of cotton. The pickers travel by scow to North Cove, on the northern shore of Willapa Bay, and spend the day gathering the moss from damp areas where it grows profusely in Pacific County's rainy climate.

Moss for Bandages

Shortages of cotton during World War I caused in part by its use in ammunition production and the tremendous numbers of casualties led to a shortage of bandages for wounded soldiers. In its place, the military turned to sphagnum moss. The moss, which grows profusely in damp climates in North America and Europe, offered a number of advantages. It grew wild over large areas, gathering it did not reduce the economic value of the lands from which it was taken, it absorbed 20 times its own weight of fluids, and it stored well.

Henry James Smith (1880-1918), a Connecticut playwright who had volunteered to manage the sphagnum moss program for the United States military, had, working with the Canadian Red Cross, determined that the species of sphagnum moss that grew in the Pacific Northwest were suitable for making bandages. In March 1918, the American Red Cross authorized the use of the moss for bandages. Smith, working with University of Washington botany professor and Red Cross Northwest Division director John W. Hotson (ca. 1870-1957), identified moss gathering locations in Washington.

According to an Oregonian article, "The largest and most valuable supply of usable moss was found on the North Beach Peninsula [now known as the Long Beach Peninsula] ... the species there is almost exclusively sphagnum imbricatum, which possesses the maximum absorbency. When Harry James Smith and Dr. Hotson feasted their eyes upon this wonderful supply of moss, the former threw up his hands in exultation and declared that it was not necessary to look any farther, because they had found enough to supply the needs of the whole allied army" ("Sphagnum Moss, Nature's Great Gift").

On the north side of Willapa Bay they found "an enormous supply of sphagnum papillosum" ("Sphagnum Moss, Nature's Great Gift").

Four Hundred Moss Pickers

Red Cross volunteers around the Pacific Northwest organized work parties to bring in moss for making into bandages. Between October 1917 and November 1918, 595,540 moss bandages were made by Red Cross volunteers in Washington, Oregon, and Maine.

In South Bend, Lincoln L. Bush (1867-1939) directed the moss drive. He enlisted over 400 pickers from South Bend and Raymond to board boats to travel across Willapa Bay to gather at least enough moss for 3,000 bandages, which the Red Cross needed by September 1, 1918. Bush had chosen a boggy area at North Cove for the picking. The Willapa Harbor Pilot warned the pickers, "Do not get dolled up with fancy shoes and fancy clothes" ("Moss Pickers").

The lighthouse keepers at North Cove, Anders (1854-1923) and Anna (b. ca. 1865) Gjertsen, provided a clam chowder dinner, and Captain Herman Winbeck (ca. 1877-1960) of the North Cove Coast Guard station served coffee.

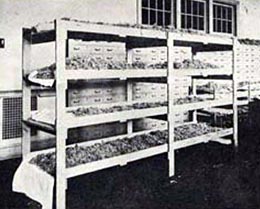

Scows carried the pickers and the 775 sacks of moss back to South Bend at the end of the day. The moss was dried in the town's lumber mill drying sheds and sent to Seattle to be made into bandages.

Around the same time, other Pacific County towns planned moss drives. Long Beach, Ilwaco, and Chinook residents gathered moss from what the Willapa Harbor Pilot called "an unlimited supply" west of Ilwaco ("Sphagnum Moss Excursion"). Three companies of soldiers from Fort Canby and local residents gathered about 90,000 pounds in April. The next day, local students and teachers spread the moss out in Ilwaco parks to dry it before shipment to Seattle.

Making Bandages

In Seattle and other Washington and Oregon cities, university students and women's clubs made bandages out of the dried moss. According to a newspaper article describing how the bandages were made, "A moss pad requires no sewing but is made by folding a layer of moss, a layer of highly absorbent paper, and a layer of non-absorbent cotton on gauze" ("Need Million Dressings").

Women did most of the work of preparing the moss and putting together the bandages, often in addition to working at home or in a workplace all day. A May 1918 newspaper article about the need for more volunteers quoted a Red Cross volunteer's admonishment:

"Men in the trenches are not taking summer vacations ... . Although we realize that the women have worked hard all winter, at best they have not spent more than five days a week working for the Red Cross. They forget that the men 'over there' are spending seven days in the week, from ten to eighteen hours a day, fighting for those safe at home ... . Every woman in Seattle should feel it is her special duty to come to headquarters and pick over the moss. Seattle women are becoming slackers when they will not assist in the making of bandages which mean the very life of thousands of men in the trenches of France" ("Red Cross").

After the War

After the war, the peacetime use in of moss in surgical dressings was continued on a small scale. A 1920 article detailing the pharmaceutical uses of moss mentioned that the Sphagnum Products Company made bandages using moss, but the industry did not develop.

Natalie N. Riegler, writing about moss bandage production in the Toronto, Canada, area, noted that the free labor and free utilization of moss beds greatly reduced the wartime costs of bandage production. The need to pay for raw materials and labor made the bandages more expensive to produce and less attractive to manufacturers after the war.