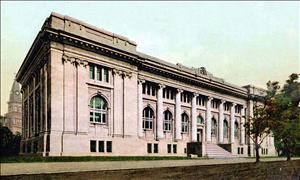

Since 1906, the city block bordered by 4th and 5th avenues and Madison and Spring streets in the heart of downtown Seattle has been the site of a succession of three completely different buildings housing the Central Branch of The Seattle Public Library. The first, an imposing Classical Revival style structure partially clad in Tenino sandstone, was constructed using funds donated by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, and served Seattle's reading public for roughly the first half of the twentieth century.

Seattle's Early Library History

About 50 of Seattle citizens -- roughly 10 percent of the town's population at the time -- met at Yesler's Hall on Front and Cherry streets on August 7, 1868, and organized the city's library association. (Some sources give the date as July 30, 1868, or August 1, 1868.) Seattle attorney James McNaught was elected president and Sarah Yesler (1822-1887) was chosen as librarian. The new association placed its first book order, funded by membership dues, in April 1869.

The group soon floundered: membership declined, books went missing, and by 1872 the group's initial energy had dissipated to such an extent that the group chose to reorganize. Sarah Yesler took on the job of treasurer, organized a strawberries and ice cream fundraiser, and began to steadily increase enrollment. By the following summer, the library association's collection had swelled to 278 volumes and 30 national newspapers. By 1881, however, membership had steeply declined and the association disbanded, donating their collection of 1,406 volumes to the Territorial University (later the University of Washington).

Try, Try Again

In 1888, with the financial encouragement of Post-Intelligencer owner Leigh S. J. Hunt (1855-1933), a group of several dozen prominent Seattle women formed the Ladies Library Association. On October 1, 1890, the library was designated an official department of the city, governed by a five-member commission and funded by a percentage of licensure fees and fines.

On April 8, 1891, the Seattle Library Commission opened a public reading room on the fifth floor of the Occidental Building at 1st Avenue between James Street and Yesler Way. On December 1, 1894, the library began lending from its 7,000 book collection. On June 28, 1894, the library moved across the street to the upper floor of the Collins Building at 2nd Avenue and James Street, and in 1896, it moved to the second floor of the Rialto Building at 2nd Avenue and Madison Street.

A final move on January 12, 1899, to the 40-room Yesler mansion at 3rd Avenue and James Street, rented from the estate of Seattle pioneer Henry Yesler (1810-1892), was intended to give the collection a permanent home. Instead, the Yesler Mansion became the collection's funeral pyre: On January 1, 1901, the Yesler building burned to the ground along with The Seattle Public Library's 25,000 books. Only about 5,000 books that were checked out at the time, about 3,000 children's titles, a handful of adult classics, and the cards from the circulation books that librarian Charles Wesley Smith hastily salvaged from the conflagration, survived.

Cash From Carnegie

The following six years were a period of extreme retrenchment. Smith and the greatly reduced collection sheltered briefly in the Yesler mansion's barn, then relocated to the old Territorial University building at 4th Avenue and University Street, which had been vacated when the University of Washington moved to its new (and present) location near Lake Washington in what became known as the University District.

On January 6, 1901, philanthropist Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919), whose generosity eventually funded construction of 1,689 libraries across the country including 44 in Washington, granted Seattle $200,000 to build a new library. Carnegie had visited Seattle in 1892, and was already in preliminary negotiations with Seattle Public Library boosters when the Yesler mansion fire occurred.

Buying and Clearing Land

On February 25, 1902, the Seattle City Council voted to purchase the city block bounded by 4th and 5th avenues and Madison and Spring streets to serve as the library site. The property, initially part of Seattle pioneer Carson Boren's (1824-1912) donation land claim, carries the legal description Block 19, C.D. Boren's Addition to the City of Seattle. The purchase price was $100,000. At the time of the sale, Seattle real estate salesman George F. Meacham (1857-1926) and his wife Lucia Mills Meacham (1866-1914) owned the entire block. The couple had quite recently acquired the property parcel by parcel, almost certainly in anticipation of selling it to the city. All of the deeds of purchase for the parcels assembled by the Meachams were recorded in the city's general recording index on October 30, 1902. The Meachams's sale of the entire property to the city was also recorded on October 30, 1902.

On January 6, 1903, the City issued library trustees a permit to clear the site. There were four structures on the property at the time, the largest of which was a mansion that coincidentally was previously owned by James McNaught, the original Seattle Library Association's first president. The structure, which had been The Rainier Club's original home and then a boarding house, was relocated across Spring Street. The former David (b. 1835) and Anna Kellogg (b. 1845) home, less grand than the McNaught mansion but still substantial, and two other smaller structures appear to have been demolished.

The property was selected against the wishes of the library commissioners, whose preferred site was part of the former Territorial University parcel, which the University of Washington regents were anxious to sell.

Peter J. Weber, Architect

On March 31, 1903, the library board announced a design competition to select the design for the new library. Thirty firms -- 10 of them from within the state of Washington -- submitted designs. The competition closed on June 1, 1903.

On August 22, 1903, trustees selected a design by Chicago architect Peter J. Weber (1863-1923). Born in Cologne, Germany, Weber received his architectural training at the Royal Institute of Technology (Technische Hochschule) in Charlottenburg. While working as a draftsman for the noted Berlin firm of Kayser and von Grossheim, Weber was assigned to work on a project in Argentina. A failed military rebellion there in July 1890 brought the architecture project to a stop. Rather than return to Germany, Weber traveled across the Americas, arriving in Chicago in the spring of 1891. That summer, Weber joined the team that was planning the World's Columbian Exposition, working as an assistant to New York architect Charles B. Atwood. When that work was complete, Weber was hired by that exposition's chief architect, Daniel Burnham (1846-1912), and contributed to many of Burnham's well-known buildings.

By 1900, Weber was working on his own and entering many design competitions. Weber was a runner up in the competition to design the Washington state capitol building in Olympia. Although he had been invited to participate in many prestigious competitions and had often been a finalist, Seattle's library was Peter Weber's first win.

Weber met with the library board on September 7, 1903, and was instructed to prepare detailed plans and specifications. Weber completed this work on December 31, 1903. Weber's dignified and imposing plan called for marble or granite cladding and fire-resistant construction, designed in the Classical Revival style.

Weber’s design for the building was included in the library’s 1904 annual report:

“The structure is 200 feet long, having its main front on Fourth Avenue, or towards the west. It is set back 40 feet from the street line, where it rises from a terrace that breaks the grade of the incline and forms a desirable setting for the building. A foreground of 20 feet is allowed on either side and is contemplated for the rear after the erection of future extensions. ... The main floor is reached by a monumental stairway from the centre of the front. Here the vestibule opens into a large or central delivery hall. At the north and south ends of the buildings are large reading rooms, 69 x 40 feet, with annexes extending 20 feet further toward the building’s centre. ... Between the reading rooms and the delivery hall are the check room, the public catalog rooms, elevator, stairways, and the women’s sitting room. Above these a mezzanine floor ... provides space for the offices and special collections and club rooms. ... the top floor contains the lecture hall, museum, and art gallery ... . The basement has one entrance at the middle of the front and two from the rear. Here, as in all parts of the building, every room except the mechanical plant has direct outside light. ... The basement contains the children’s reading room and classroom, and the newspaper room, patent and document room, men’s conversation or smoking room, rooms for the branch delivery system, bindery and store rooms, toilet rooms for men and women, and heating and ventilation room” (p. 11-12).

Delays and Other Difficulties

The library board waited impatiently for the Seattle City Council to decide the exact grade of 3rd and 4th avenues, whose regrade was in the planning stages. The new library's exact positioning on its 4th Avenue lot was dependent upon the relational grade between 3rd and 4th avenues. "The question rests with the property owners [along 3rd Avenue] who are divided and seem as far today from unanimity as they ever were," opined The Seattle Daily Times (October 29, 1903). The contract for regrading 3rd Avenue between Yesler and Pine streets was not let until September 1905, and the subsequent regrade of 4th Avenue resulted in the eventual need to accommodate the change in grade by constructing a large stairway.

On March 1, 1904, the board of trustees opened construction bidding, but all five firms submitting bids came in well over Carnegie's promised $200,000. In an attempt to economize, Weber re-envisioned the building's exterior in more affordable Tenino sandstone (quarried in nearby Lewis County), while the back, which faced 5th Avenue, was clad even more humbly in brick. The top floor of the building would be left unfinished, a space for possible expansion if and when funds allowed.

On April 15, 1904, the Seattle firm of Cawsey & Carney won the construction contract with a $196,400 bid. Their winning bid was still so high as to pre-empt the library board's ability to purchase such necessities as library furniture. Andrew Carnegie eventually saved the day again, donating a further $20,000 at the request of St. Mark's Episcopal Church rector and library board member J. P. Derwent Llwyd (b. 1861).

Construction began the following week, but by September serious trouble had arisen. "Library Building Sinking On South -- Big crack in Madison Street wall causes suspension of work," trumpeted The Seattle Daily Times (September 28, 1904).

The contractors blamed the problem on the then-ongoing construction of the Great Northern Railway tunnel, a one-mile-long tunnel that runs beneath downtown Seattle from Alaskan Way (below Virginia Street) on the waterfront to 4th Avenue S and Washington Street. The Great Northern Tunnel was 28 feet high and 30 feet wide, the largest, although not the longest, tunnel in the nation, carrying both the Great Northern and Northern Pacific rail lines. Tunnel construction had begun on April 14, 1903, with excavation proceeding from both tunnel entrances toward a planned meeting about 125 feet beneath downtown Seattle.

Great Northern construction engineers denied responsibility. The two tunnel construction crews met under the west side of 4th Avenue between Seneca and Spring -- cattycorner to the library construction site. It took several months of legal wrangling for library trustees to secure a damage settlement of $100,000 to repair the problems and continue construction.

A Magnificent Building.

The new building was finally dedicated on the evening of December 19, 1906. The Seattle Times reported triumphantly:

"The doors of the new Carnegie Public Library will be opened at 7:30 o'clock this evening when every part of the magnificent building will be accessible to visitors. At 8 o'clock the program of exercises, including the formal presentation of the library to the city, will commence in the lecture hall on the second floor in the southern part of the building. The exercises will open with music by Wagner's Band and an invocation will be pronounced by Bishop Keator of Tacoma. ... The opening will be an informal affair, open to all after the invited guests have been accommodated. The engraved invitations sent out were merely in the nature of souvenirs and there will be no reserved seats" (December 19, 1906, p. 4).

The building's wonders included what was lauded as the largest children's reading room of any American library; a grand central atrium; a men's smoking room and a women's reception room, both furnished stylishly and comfortably; a large public lecture hall; a large circulation room boasting open shelves and 20-foot ceilings; electric elevators, a telephone system, and coal-fired heating plant -- and the books, of course, more than 15,000, with capacity for an eventual 200,000.

Muddling Through

Alas, only a few days later the newspaper was lamenting the public's difficulties even getting into their shiny new facility. Under a headline "Mud Interferes With New Public Library," The Seattle Times reported:

"Seattle's new public library is to all intents and purposes inaccessible. Unpaved streets, lack of sidewalks, and the accompanying accumulation of mud are serving to seriously embarrass library patrons. Owing to the regrade of Third Avenue it is impossible to reach the library building from downtown unless the Madison Street cable cars are used. When one leaves the car it is to become lost in a veritable wilderness of mud. Fourth Avenue is unpaved and unplanked and there are no walks on the east side of the street" (December 21, 1906, p. 16).

Book lovers muddled through, and by the end of the library's first full year of operations, the number of borrowers had increased by 94 percent, from 9,889 to 19,229. Internal expansion began almost immediately. The public meeting room was converted into a reading room for periodicals, and the book collection increased.

Between 1907 and 1909, 4th Avenue was lowered and widened, further increasing the difficulty of getting to the library. The Seattle architecture firm of Somervell & Cote was hired to design grand new entrance stairs and terraces.

Crowding and Expanding

In 1907, longtime librarian Charles Smith announced his retirement. His replacement was Judson T. Jennings (1873-1948), a New York native and formally trained librarian with many years of library service. During what would be a 35-year tenure, Jennings would increase the library's emphasis on adult education, build the reference collection and reference services, guide branch library construction, and shepherd the library through the dire years of the Great Depression.

Upon his arrival in Seattle, Jennings assessed usage levels at the Central Library and expressed the opinion that an immediate expansion was warranted. Over the years, Jennings pled for expansion in his annual reports, and in 1916, the building was expanded to the rear. The expansion accommodated the library's bindery/mendery and the catalog department, which Jennings considered a stopgap measure only.

By 1919, Jennings's report enumerated overcrowding in the reference and circulation departments, staff areas, and book stacks. Needed areas -- for which there was no room -- included a reading room for blind patrons, a room for books in languages other than English, a soundproof room where recorded or piano music could be played, a space dedicated to the shipping department, and more room for the telephone exchange.

Seattle's library lacked space for public meetings, Jennings emphasized, unlike Portland's new facility. "A surprisingly large number of the Portland organizations hold their meetings regularly at the library, making it something of a civic center. Such use should be encouraged and facilities for it should be provided here," Jennings opined (quoted in Marshall, p. 58).

Dire Times

During the 1930s, all branches of The Seattle Public Library experienced greatly increased usage, as the ranks of the city's unemployed workers grew. The library served as an ad hoc social agency, a place to read want ads and to look for work, and simply a respite for thousands of residents who had no other place to pass the time.

Funding for library services, as for other public services, was slashed. Employees were let go in response to ever tightening budgets. By 1933, the library's budget had been reduced to only half of where it had stood two years before. Book and periodical purchases slowed to a trickle. Even the restrooms at the Central Branch, formerly staffed by attendants, were closed and padlocked.

The advent of federal works projects in late 1933 brought the library some relief. By 1935 federally paid workers were performing labor and maintenance tasks, and 55 WPA (Works Progress/Progress Administration) employees were assisting with clerical work.

Staff and Friends

In 1935, library employees organized The Seattle Public Library Staff Association. The group formed committees to study staff problems -- lack of pension, cuts to hours and vacation, staff reductions -- and to promote the improvement of library services. In 1939, the staff association helped facilitate the beginnings of what would become The Friends of The Seattle Public Library, an important support group that raises funds to aid programs that exceed the library budget and that advocates for the library.

A series of public meetings in library branches culminated in a dinner at The College Club in downtown Seattle on January 16, 1941, where 90 supporters (including staff members and library board members) gathered to organize the Friend’s group. Beryl S. Gridley (b. 1896) was elected president. On March 15, 1941, Seattle attorney and Friends vice-president George Mathieu (1892-1974) filed the group's articles of incorporation with Secretary of State Belle Reeves (1871-1948) in Olympia.

Among the group's purposes, as stated in their bi-laws, were "To enable the library to serve fully as a 'People's University'" and "To work for the library in season and out" (The Seattle Times, March 23, 1941, p. 15). One thousand Seattleites received an invitation to become charter members of the Friends. In order to encourage membership and wide support, dues were set at 50 cents per year.

On April 25, 1941, the Central Library and all 10 branches held open houses to mark the 50th anniversary of The Seattle Public Library. The Friends group organized the celebrations.

War Years

In 1942, longtime city librarian Judson Jennings turned 70, the mandatory retirement age at the time. Upon his retirement from The Seattle Public Library, Jennings became the first chair of the newly created King County Rural Library District (Now King County Library System), jump-starting that organization through the benefit of his nearly half-century of library expertise. John S. Richards (b.1892), formerly the associate director of the University of Washington library, succeeded Jennings at The Seattle Public Library.

During World War II, the library struggled to provide service to a patron base that expanded increasingly as armed services members and war workers flooded the city. Although these newcomers were not permanent residents, the library granted them full privileges from the outset of the war. The military, Boeing, and government agencies all required quick and voluminous service, relying especially on the library's extensive technical book collection. Library services for the civilian population included an expanded collection of books related to wartime conditions, civil defense materials, technical books, Red Cross materials, and well-attended training sessions for home front civil defense and Red Cross work.

Library book circulation figures dropped during the war. On the home front, library users coped with food rationing, round-the-clock war production work at Boeing and in shipyards, gas rationing, the need to juggle child care as women took up jobs men had vacated to join military branches, and lighting dim-outs at night. The stress of living in a world at war changed reading habits, opportunities, and inclinations.

The forced evacuation of Seattle's Japanese American community also greatly affected library usage patterns. Five-year Seattle Public Library trustee Clarence Arai (b. 1903), a prominent Seattle attorney, was among the almost 10,000 Seattle and King County residents forced into internment. The library continued to serve these patrons as best it could, sending nearly 7,000 volumes, including many Japanese language books, to the internment Camp Minidoka for the use of those interned there. After the war, the volumes were returned to Seattle and to the regular collection.

A Postwar Boom

After the war ended, library patrons flooded back, eager to pick up the threads of pre-war life and for current information to guide them in a changed world. The Central Library strained under increased usage, and library staff struggled to fit more patrons and more materials into what had long been less-than-adequate space. The lack of community-gathering space in the Central Library was especially vexatious.

Rather than expanding the Carnegie-funded building, John Richards began pressing for the erection of a completely new facility, perhaps abutting the rear of the older structure, which could then be converted to non-public use. The entrance to this imagined modern facility would have faced 5th Avenue, rather than the Carnegie's 4th Avenue approach. Another plan called for remodeling the Carnegie building and creating a rear addition. Either of these plans would have immediately reached capacity of use, so did not really solve the problem. How to pay for any of this was another question -- The Seattle Public Library was still woefully underfunded, its staff some of the lowest paid library workers on the entire West Coast.

1950 Library Bond Issue

An underground structure to house overflow from the book stacks designed by Seattle architect John Paul Jones (b. 1892) was built in 1949, using a combination of state funds and cumulative reserved funds. Sited below the 5th Avenue side of the Carnegie site with a public park at ground level, the book stack was not physically connected to the original structure. The book stack building was envisioned as the first component of an eventual completely new library. John Paul Jones drew plans for this new library, and built a model that was displayed to the voting public.

To fund construction, library trustees placed a $5 million bond issue on the 1950 city ballot. Of that amount, $4.5 million would pay for the new central library, with the balance funding construction of much-needed branch libraries in Ravenna, Magnolia, Greenwood-Phinney, Capitol Hill, and Ballard. This was the first bond measure ever put before Seattle voters.

The Friends of Seattle Public Library, library trustees, and staff sprung into action, holding public meetings and educating the public about why the bond issue should be approved. The Seattle City Council favored the bill. A supportive editorial in The Seattle Times on April 22, 1949, called libraries "the one cultural and educational institution that reaches into the lives of almost every resident. Aside from the 'book stack' now under construction, Seattle has spent almost nothing on new library buildings for years. The time is at hand to begin making up for past omissions" (p. 6).

The library's many blind patrons stood to gain from the bond issue. Facilities housing the Braille collection, moved decades earlier from Central to the Fremont branch to gain space downtown, were inadequate -- crowded into the cramped basement space and difficult to access. If approved, bond moneys would include space in the planned Capitol Hill branch for services for the blind.

Meanwhile, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake struck Seattle on April 13, 1949, damaging and seriously weakening the Central library, but not enough to close it. Librarian Richards warned that further temblors would likely bring about the building's total collapse. Despite this risk, and even in the face of heavy lobbying efforts, Seattle voters shot down the library bond measure in the November 7, 1950, election. A $1,500,000 measure to fund purchase of a site for a civic-arts center was also rejected.

Soldiering On

Librarian Richards lay blame for the failed bond issue on citizen apathy, and vowed to build the Friends of Seattle Public Library into as powerful a lobbying force as the Parent Teacher Association (PTA). Many Seattle residents apparently did not actually use the library services and felt no need to be taxed for them, and others still thought Andrew Carnegie (who had died in 1919) either was footing or should foot library bills.

Luckily, library trustees still had access to $156,000 left over from construction of the book stacks facility. This money was quickly spent to repair the worst of the earthquake damage and tackle some remodeling. The former newspaper room was converted into a community auditorium -- newspapers were moved elsewhere since moving books into the new stacks building had opened up space.

On March 11, 1952, Seattle voters rejected a $1.5 million bond issue that would have funded construction of seven neighborhood branches and additions to two existing branches. A city budget cut in 1954 led to all day closures on both Saturday and Sunday at the Central branch. The resultant increased use during the week stressed staff -- and the building -- to the breaking point.

Bond Issue Victory -- At Last

These difficulties did, however, draw widespread public attention to the Central branch's dire situation. Public support for library funding, whipped up by the Friends, staff, and other library supporters, strengthened.

On December 20, 1955, the Seattle City Council placed a $5 million library bond issue on the March 13, 1956, ballot. If approved, the funds would cover the construction of a new Central library and, if possible with funds allocated, one or two branch libraries.

This time, finally, Seattle voters approved the measure. "Patrons of Seattle's venerable Central Library and friends of the public library system are elated ... . The edifice that has served as headquarters of the city's library service for half a century can be replaced with a modern structure, more in keeping with Seattle's growing population and with new developments in library science," ran an editorial in The Seattle Times (March 14, 1956, p. 8). Library services were relocated to the former headquarters of Puget Sound Power & Light Company at 7th Avenue and Olive Street, and demolition of the Carnegie Central branch commenced.

The library board debated salvaging the Carnegie building’s old stack shelving, but concluded that “because they are not modern type, it would be costly to fit them in the new building -- even in the basement” (1957 Minutes, p. 281), and sold the sturdy shelves for scrap. The Seattle firm of Methany and Bacon won the contract to demolish the Carnegie structure with a bid of $52,400 including tax.

The new building, designed by Leonard Bindon (1899-1980) and John L. Wright (b. 1916) in association with the firm of Decker, Christiansen & Kitchin in the then-popular International style, opened in 1960, on the same site. This building was in turn replaced in 2007 by an award-winning structure designed by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas (b. 1944), again on the same site.