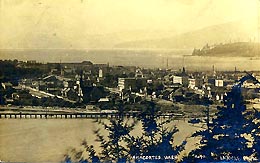

The City of Anacortes is located in Skagit County on the northern end of Fidalgo Island in Puget Sound. It is the only incorporated community on Fidalgo, which is separated from the mainland by the Swinomish Channel. Highway bridges link Anacortes to the mainland and to Whidbey Island to the south. Samish and other Northern Straits Salish peoples have inhabited the land in and around Anacortes for thousands of years. Permanent non-Indian settlement began in the 1860s. Anacortes was incorporated in 1891 with an economy based on lumber, fishing and fish processing, and farming. These industries thrived for many years before facing decline in the mid-twentieth century. Several oil companies selected Anacortes for refineries in the 1950s. Refining, tourism, residential and retirement housing, and commercial retail have come to dominate the local economy.

Samish Society

The rhythm of Salish life revolved around the seasonal round of food gathering from spring through fall followed by communal living in villages during the winter months. In the 1700s Samish bands occupied three villages just north of Fidalgo Island -- two on Guemes Island and one on Samish Island. Here community members would gather for the winter and live on the stored abundance of the earlier months. The villages each consisted of several communal longhouses. The houses were made of cedar, as were many other tools and the canoes used to travel between the islands and to the mainland.

From the spring through the late fall, people obtained a tremendous variety of food from the lush forests and waters. Camas roots grew in the vicinity and many other plants proved edible and nutritious. As summer wore on the berry bushes provided the sweetest treats -- red huckleberry, salmonberry, blackberries, and even cranberries among others. Shellfish were harvested from the many muddy tideflats around the islands. Mammals such as deer, elk, and bear were hunted with bows and arrows or captured and dispatched in pit traps. Waterfowl could be carefully and skillfully netted. But the most important food was the salmon, which was both plentiful and nutritious.

Disaster befell the villages in the late 1700s as the first wave of terrible plagues swept northward through Puget Sound. It is estimated that the Samish lost about 80 percent of their population, falling from several thousand to about 200 people. The survivors abandoned the villages on Guemes Island and gathered in one village on Samish Island.

More changes came as local communities were pulled into the global fur trade centered in the 1780s at Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island. At first, other Native traders brought new European goods -- cloth, blankets, muskets -- to exchange for beaver pelts, but by about 1820 the first fur traders and trappers from outside the region were crossing the Cascades and settling in local communities. Now the beaver pelts flowed toward the newly established forts of the Hudson's Bay Company -- Nisqually, Victoria, and Langley.

Quiet Days and Big Dreams

The fur trade dwindled in the 1840s and the first permanent settlers did not reach Fidalgo Island until the early 1860s. Most of the earliest settlers were single men who married Indian women. The first white woman, Almina Richards Griffin, arrived in 1869. By 1872 a few tiny cabins dotted the future city of Anacortes and an equally tiny schoolhouse, which early settler and historian Carrie White noted was "ventilated by its cracks -- altogether too freely by those in the floor during the winter term," stood to educate the handful of children on the island.

These early settlers included farmers such as William Munks, Enoch Compton, the brothers Charles and Robert Beale, and Hiram March. Munks, who claimed to be the first permanent resident, managed to become the community's first justice of the peace (1863), coroner (1866), postmaster (1871), and notary public (1872). He also opened the community's first store in 1870. None of these activities required enough effort to prevent him from also establishing a flourishing farm. Another pair of early settlers was Amos (1839-1894) and Anna (1846-1906) Bowman. It was Amos Bowman, who became the tireless promoter of the fledgling community, who gave the settlement its name -- a stylized contraction of his wife's maiden name, Anne Curtis.

Mail service arrived in 1868, but for decades the Fidalgo Island community remained quiet and isolated. Farm produce was sold and supplies purchased in the nearby boom town of Whatcom or, for better prices, in Victoria. The first road, built in the years 1873-1879, ran from March Point across the island, but most transport went by sailboat even after the arrival of steam ships in the late 1870s. After that, Fidalgo was a small stop for ships like the Fanny Lake which made the "Skagit River run" until 1883 and then the Bellingham Bay route, which reached a peak in 1891 before yielding to the railroads.

Not content with the slowly growing farming community, Amos Bowman erected a small sawmill on the island in 1882 as much in the hope of spurring development as to meet what would have been a very minimal local demand. He also began promoting the idea of Anacortes as the natural terminus of the much anticipated railroad expansion across the north Cascades to the Pacific. But Anacortes would have to bide its time as railroad rumors swirled and actual progress stalled. Logging had begun in the mid-1870s and continued on Fidalgo through the 1880s, with half-a-dozen camps cutting the old growth timber, but the huge logs were boomed down to the big Utsalady mill on Camano Island.

Despite the slow growth, Amos Bowman continued to spread the word about the great expansion that Anacortes would enjoy -- as soon as the railways arrived and rendered the town the final link of the American empire. There was more sense in his claims than in those made by boosters of some other aspiring metropolises. Indeed, Washington's first territorial governor, Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), had once favored the location after a thorough study of the coast. The deep harbor of Fidalgo and Ship Bays, the still plentiful old-growth timber, and the rain shadow created by the Olympic Range could all plausibly be used to attract attention.

Anticipation quickened in Anacortes, and in all of Skagit and Whatcom counties, in 1888 as a frenzy of railroad building seized the region. The Fairhaven and Southern Railway Company ran rails from Bellingham to the town of Sedro by 1889, while the rival Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Company had thousands of men working on lines north and south of the Skagit River. But the hope of Anacortes lay in the Seattle and Northern Company, which incorporated in 1888 with the stated goal of building from Seattle to Canada and constructing a much-anticipated northern line across 200 miles of the high Cascades and the Columbia Plateau to the rail hub of Spokane (Chechacos).

Hope remained high, but the population remained low in Anacortes in 1889. A rail line from the city had begun in the summer of 1888, spurred on by a 2,000 acre land grant offered by the Bowmans and three other settlers. Enough had been accomplished in the first year to collect the land grant, with further development planned for the next year.

Boom and Bust

Important change came early in 1890 as the powerful and established Oregon Improvement Company went all-in for Anacortes, posting an astonishing $15 million in bonds to develop the town. The conditions were ripe for a boom and Anacortes did not disappoint. Money poured in as people invested huge sums in small lots they had never seen and real estate agents invaded the town. The February 1st edition of the Anacortes American touted the credentials of one new arrival, "Mr. D. A McKenzie," who sold house lots to feverish newcomers from his office "temporarily located in a tent on the corner of…Fourth street."

Population statistics tell the story. On January 1, there were about 40 residents and already 500 by the end of the month. The population quadrupled to 2,000 by the end of February and kept rising through the summer. The swelling population found ready employment in the rush to build an instant city, bankrolled by bonds from the Oregon Improvement Company.

Much of the lumber for the boom came from a mill owned by tireless town promoter Amos Bowman. On February 1, 1890, the

Anacortes Progress

reported that Bowman had purchased a full sawmill and hired a crew of bricklayers from Seattle to start a large lumber mill in Anacortes. This inaugurated a tremendous industry that would bring numerous jobs to the town. Although Amos Bowman would live only until 1894, he once again anticipated Anacortes' potential as a lumber town and set the stage for the expansion of the lumber industry.

As spring came, tents under towering trees gave way to houses as the trees were felled and the saws of Bowman's mill ran around the clock. Soon four lumber mills were up and roaring. So much wood was milled that the first streets of Anacortes were actually laid over with thick wood planking. A brick factory was built overnight and churned out its product for the business district, residences, and two opulent hotels. The Anacortes Hotel "had a splendid dining room with ... waiters in full dress and fine silver and linen for the tables" (Chechacos).

By August the town could boast thousands of residents and the beginnings of an electric trolley line. Water works had been constructed with clean water flowing down to the city from nearby lakes. All seemed well and prosperous. On August 5, 1890, daily railroad service between Anacortes and the town of Sedro commenced, connecting southward with branches of the Northern Pacific.

The bust that immediately followed completion of the railroad was caused by the sudden financial collapse of the Oregon Improvement Company in August 1890. With no more funds available to pay workers, thousands left town as quickly as they had come. Much money was lost and the energy of the eight wild months skidded to a halt. Also, the proposed direct rail line from Anacortes through the Skagit River passes of the Cascades could never have been remotely profitable given the route's sparse population and massive construction costs. The most dismal fate befell the city's electric trolley. Finished at great effort and cost, it ran across the island for one day, March 29, 1891, and never moved again. There simply was not enough money to buy necessary generating equipment.

Incorporation

Recovery proved slow and inconsistent, but not all the gains of the previous year departed with the bulk of the residents. Anacortes had a water works and saw mills, planked streets, and residences in every state of construction. It also retained the determined original settlers and newcomers who desperately hoped to recoup their losses. The two local papers continued to print booster promises in the boldest type, funded by the remaining businesses. A typical full-page ad appeared in the Anacortes American on January 26, 1891, sponsored by seven real estate, insurance, and banking agents:

"The Future Great City of Puget Sound Will Be ANACORTES…Her Unique Position Assures It. Population has increased by over 10,000 per cent in the past year. $1,520,000.00 have been expended in improvements in a city whose population a year ago was 25 persons. Has 6 miles of graded and paved streets, 12 miles of street railway, city water works, four large ocean wharves, the finest agricultural coal, lumber and mineral region in the state, adjoining, superb scenic surroundings, and is the extreme western terminus of the Northern Pacific railroad."

The advertisements ran from February through April. The number of sponsors dropped to six on March 5 and down to five on the 12th and then persisted until April 23, when they ceased altogether.

Facing the difficulties of the local depression, the residents decided to apply for incorporation. This sensible step allowed the townsfolk to consolidate what remained and organize their resources. The town received a telegram announcing their successful petition as of May 19, 1891. The editor of the Anacortes American wildly rejoiced that despite his dignity "we can hardly resist the temptation of standing out beneath the stars and yelling out like a mad enthusiast over the joy tugging at out heart strings."

Despite the many difficulties it faced, Anacortes now had municipal leaders, led by mayor-elect Captain Frank Hogan. Those leaders were first chosen in an election held while waiting for confirmation of incorporation and, when that that election was invalidated due to an unknown number of votes cast by non-residents, a second election produced the same results.

Salmon, Saw Mills, and Packaged Cod

Following the boom, bust, and incorporation, Anacortes did successfully attract new industries.

One of the major developments in the first year of incorporation came in the person of J. W. Matheson, who hailed from Massachusetts. He arrived on the sound eager to find a base for his schooner Lizzie Colby, which would soon be employed in the cod fisheries off the coast of Alaska. Matheson chose Anacortes as a base from which he hoped to not only catch but also package and ship cod.

For this purpose he constructed a curing plant that was ready for operation when the Lizzie Colby arrived with 45 tons of fish on October 14, 1891. In subsequent years, not only the captains but many of the crewmen for cod fishing boats hailed from the East Coast. Captain Matheson soon employed dozens of professional fishermen from Gloucester, Massachusetts, who brought their expertise to the Pacific coast. The new industry expanded rapidly and attracted more entrepreneurs. In 1904 another Gloucester captain settled in Anacortes, built a cod-curing plant, and added two new schooners to the Anacortes fleet.

Although fish-processing began with cod, salmon canning soon far-exceeded even the growing cod industry in Anacortes. The salmon cannery began in 1894 with the Alaska Canning Company. In 1896 a clam cannery opened, but the plant soon switched to salmon. The industry continued to grow until 11 canneries lined the wharfs by 1915.

Employing a diverse work force, including many Japanese, the canneries created controversy over wages and race. Some whites resented that Japanese employees would work for lower wages and cannery operators replied that the industry required lower wages or no wages, although at times a plant would lay off minority employees.

But a diverse population remained in Anacortes and in 1919, one editorial in the Guemes Beachcomber leveled a diatribe -- no doubt heightened by the recession following the end of the world war -- against the numerous Filipino, Hawaiian, Puerto Rican, and black residents of the community. The author also opposed giving Japanese workers citizenship. Despite such public opinion, ethnic minorities' willingness to work for lower wages kept them in the city.

Settling In

The first three decades of the twentieth century were good for Anacortes. Logs still flowed into town mills for conversion into lumber, shingles and boxes. Canneries set records and brought millions of dollars in wages to the city. Mills frequently burned to the ground, but the city gradually improved firefighting services. Mill owners usually rebuilt rapidly and with newer equipment following a fire, as the big Rodgers mill did in 1905.

Having established a solid industrial base, the city could turn greater attention to the cultural side of life. A Carnegie Library opened in 1910 and Chautauqua meetings were popular in the summer. A three-citizen park board was established in 1914 and several hundred acres of land was set aside for what would become Causland Memorial and Washington parks. Both areas were improved in the 1920s.

The Port of Anacortes, the last to form of the state's 11 deep-draft public ports, was approved by local voters in 1926. The port district facilitated the continuing export of wood and cannery products. Fishing was and remains a crucial industry for the port district. The city honored this tradition with the Marineer's Pageant which developed in the 1930s and ran off-and-on into the 1950s. More recently, the Seafarer's Memorial was dedicated in August 1976. The statue listed many names of local men who had died at sea in the previous decades. No one could have realized that, in a few short years, some of the boys attending the dedication would have their own names added to the monument after the worst disaster in the history of United States fisheries.

On Valentine's Day, 1983, two Anacortes fishing vessels, the Altair and Americus, capsized off the coast of the Aleutian Islands in the Bering Sea. Fourteen local men were lost. The first news that reached town was that the Americus was lost and the Altair missing. Thousands of stunned residents soon gathered for a prayer vigil and later for the memorial services. Mystery added to the grief as the boats were lost in calm conditions and weeks of fruitless searching for survivors and for the missing Altair dragged on into a two-year inquiry. The inquiry concluded that the most likely cause of the tragedy lay with instability stemming from recent modifications to both ships. (See Lost At Sea: An American Tragedy for a full, riveting account.) The names of the 14 men were later added to the 96 others whose names commemorate the blessings and grief of a community tied to the sea.

Although the boom and recession of World War I impacted the local community, the town's identity as a blue-collar lumber, fishing, and cannery town continued unabated. A growing community of Croatian immigrants added their cultural flavor, one that continues to the present. Churches played a role in ethnic identities with the Croatian immigrants congregating in the Catholic church and Swedish and other northern European immigrants favoring the Lutheran denomination.

Depression, Recovery, and Changing Markets

There is no disguising hard times. Following the crash of 1929, Anacortes soon faced the protracted effects of the Great Depression. But the city persisted and relief came from local charities and then the federal government. Some mills and canneries closed, but enough remained for the citizens to eke by through the lean years.

Anacortes was always a union town, and some residents also put their weight behind socialist activities. The city's first precinct voted for Socialist candidate Eugene Debs in the 1912 presidential election. As conditions deteriorated in the thirties, a movement advocating the Townsend Plan -- a proposed old age pension that preceded Social Security -- became popular. A Townsend Hall was opened in Anacortes during the 1930s and served as a center for left-wing politics.

The first three years of the Depression, from 1930 to 1933, were the toughest. For example, the Woods mill reopened in July 1933 after a three-year closure due to poor market conditions. By 1940 the Depression was largely over and a nudge in defense contracts began to revive prosperity. With the coming of open war at the end of 1941, Anacortes, along with the rest of the nation, went into an economic overdrive that is almost unfathomable today. Unemployment became a 15-minute coffee break. Wages were high, hours long, and town pride rebounded with residents knowing they were doing their part in the war effort. Many war bonds drives tapped the patriotic spirit and the heavier wallets of the city's residents.

Following the war, 20 more names of local men killed in action were added to the memorial at Causland Park while the city worked to keep the economy stable. The post-war boom continued without a major recession and the economy transitioned back to a peace-time footing. But by the decade's end, increasing economic and environmental pressure begin to challenge the saw mills and salmon canneries that had been the identity and financial lifeblood of the community for 60 years.

Community debates swirled around the problems confronting the town. Resident Amelia Heilman proposed that the community buy-in to Dr. Richard Poston's message of self-help for local communities. Poston ran the University of Washington's Community Development department and agreed to work with the city after a small team of residents cajoled him into accepting their petition.

Poston came to speak to the town on March 14, 1951, and the Anacortes American reported that the plan he advised was a "strictly self-help idea, and Poston stresses its aim of rebuilding self-reliance and getting away from excessive dependence on government. Poston sees it as part of the battle of democracy against Communism." Poston touted the revival of the town of White Salmon on the Columbia River as proof of his plan.

Momentum built over the next two years. On September 16, 1953, two hundred concerned townspeople met and elected 37 program leaders. Scott Richards, local businessman and past chairman of the Chamber of Commerce, was chosen to head the committee. The organized population analyzed everything about the town:

"During its 17-weeks of study, action and evaluation, [the program] included more than 1,200 dedicated citizens. Every facet of the community came under scrutiny — schools, churches, businesses, youth activity, civic and fraternal organizations — a complete census on the part of one particular committee whose members knocked on every door, peered under every stone for an accurate count" (Funk, "1950-1969").

The town emerged with lots of data and ideas and an energized populace looking for a new way forward. In fact, a decade later in 1962 a new crop of dedicated boosters would win the title of "All-America City" from Look magazine and the National Municipal League for the city's improvements in education, healthcare, and infrastructure. But even before the 1953 community study got under way, the main force for economic revitalization arrived from an entirely new direction, unknown to all but a few residents until the news broke early in that summer of 1953.

Big Oil

The entire front page of the June 2, 1953, edition of the Anacortes Bulletin reads "SHELL PICKS LOCAL SITE." Secret negotiations between the oil giant and local real estate holders on March Point, a peninsula facing downtown across Fidalgo Bay, had been carried out quietly for months with only vague rumors of "something big" spilling out into the streets. The company picked Anacortes over rival Bellingham because of the harbor, rail connections, and the simple fact that they had to pick one or the other. Immediately after the announcement the president of Bellingham's Chamber sent a telegram of congratulation to his counterpart in the Anacortes Chamber.

Within a week, a city planning consultant had been hired to give advice as to the best way to prepare for a new industry that planned to employ 600 (besides 1,500 in the construction phase). The planned development also meant many new jobs in the service sector. And the city held its collective breath hoping that Shell would not get cold feet or geologic tests compromise the city's future. Wallie Funk, then co-owner of the Anacortes American, wrote an editorial about the excited mood of the town:

"Townspeople are doing a huge business in rumors. It's getting so you can't look sideways at an empty lot or make a regular monthly payment on your house without drawing a few looks as the front man for an industry, department store or luxurious motel" (American, June 25, 1953).

He continued with a caution drawn from the stubborn history of the town, stretching all the way back to 1890:

"Those who are familiar with this community seem to take the sweet (in this case Shell Oil) with a grain of salt. Their disappointments in chromium, aluminum, government laboratories, smelters, mills and other prospective giants are a matter of record in Anacortes dating back to the boom and bust of 1890" (American, June 25, 1953).

Objecting to the raw enthusiasm that Amos Bowman would have appreciated, Funk detailed each time that the town had been left at the altar. But this time the hope fulfilled its promise and Shell built its new $75 million refinery. In fact a second refinery -- Texaco's -- followed in 1957. The new industry arrived just in time as the 1950s and 1960s saw a slow-down in logging and a sharp drop in the fisheries. A new era had begun and the youthful, optimistic foot soldiers of the Poston committees could only embrace the town's transition from logs and cans to oil and services.

Preservation Efforts

One of the striking aspects of Anacortes today is the amount of land around the city that has been preserved for recreation and wildlife habitat. This happened for several reasons and also through the community's long-term commitment to preserving green areas.

A desire to preserve the natural beauty of the forests and the need for clean, uncontaminated water inspired early conservation efforts. At the time of incorporation in 1891 the Oregon Improvement Company pumped water from nearby Cranberry and Heart lakes into town, and 10 years later the City purchased water rights to secure this supply for the long term. It was recognized that the forests surrounding the lakes were vital for preserving pure water and recreational access to the lakes was prohibited. In 1919, the City purchased Washington Power, Light, and Water Company which had retained land around the lakes.

By the late 1920s the City needed more water than the lakes could provide and so acquired water from the Skagit River in 1931 at considerable cost. This marked a sharp change in the status of the city's forest lands. No longer needed as a natural filter for clean water, the forests around the lakes became valued as lucrative resources to pay for the new water system. However, at the same time, the lakes became available for recreation by the community.

In addition to land that had been acquired to protect the aquifers, private individuals had begun donating land to the City for conservation. From 1929 to 1934, private individuals donated hundreds of acres around Cranberry Lake and nearby Mt. Erie with the intent of preserving the land for park use. In the coming years, much more land was donated and acquired until the City controlled nearly 2,200 acres in 1970. However, the City continued to cut some of the forest to pay for expenses and to develop some parts of the forest into park spaces. The tension of this multiple-use policy persisted into the 1970s as pressure mounted to end logging on the city's forest lands.

By 1981, the City developed the Anacortes City Forest Land management plan and stressed sustainable logging. Money from timber sales paid for trail construction, maintenance and a trail guide. Meanwhile, a local conservation group, Friends of Forest, organized to end logging of city land. To do so, an alternative source of income was needed. By 1990, the City had approved the Forest Endowment Fund to support the environmental education program and in 1991 the city council banned logging of the Anacortes City Forest Land. But it wasn't until 1998 that the community created a conservation easement program in which the City agreed to protect one acre for every $1000 raised. Interest from these funds would pay for the expenses of maintaining the property. The program has been a huge success, with nearly 2,800 acres sponsored for protection by 2009. That equates to about one acre of protected forest for every six people in Anacortes.

Anacortes Today

Surrounded by ample parks and protected forests and the gray waters of Puget Sound, Anacortes has increasingly appealed to retirees. Large housing tracts went up in the 1960s and continue to expand today. Of the early industries, the lumber mills have gone and the canneries are closed, but fishing and fish processing remains alive and well at the town's three large seafood processing plants. And fishing vessels continue to make the annual trek to the cold waters of the north Pacific.

An increase in tourism has also impacted Anacortes, especially as the "Gateway to the San Juans." Tourists flock through the town in the summer months and congregate at the Washington State Ferry terminal near the northwest tip of Fidalgo Island for sailings to Lopez, Shaw, Orcas, and San Juan islands. Since the 1960s, Anacortes residents have promoted arts and crafts, partly in an attempt to attract tourists, and the first weekend of August marks the annual Anacortes Arts Festival. Other community groups and promotions work to maintain the civic pride of a city whose residents, like those everywhere, have left far behind the identities of union, mill, dock, and cannery for the trappings of global media.

As with the study group of the 1950s, civic leaders continue to fight for the preservation of the historic downtown retail center and the establishment of a stable tax-base for the long-term. It may be that the twenty-first century will continue the story of an innovative community, one willing to embrace new and unexpected opportunities.