On August 21, 1886, Civil War hero William Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1891) arrives in Seattle for a five-day visit. He will take a steamer tour of both Lake Washington and Lake Union, speak at a "camp fire" at Brown's Pavilion, and attend a fantastic clambake on Alki Point during his visit, which will be remembered by all for decades to come.

A Lovely Lake Tour

In 1886 the Civil War was over by only two decades. Anyone 30 or older could remember it, and they all remembered Union General William T. Sherman, who was considered a hero by most in the West. Thus it was big news indeed when Sherman and his daughter Lizzie (1852-?) arrived in Seattle by train on Saturday evening, August 21, 1886. They were escorted to Pioneer Square’s Occidental Hotel where, after a musical welcome by the First Battalion Band, the general was personally greeted by veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.), a fraternal organization of Union veterans formed after the Civil War.

Sunday was mostly a day of rest for the Shermans, but 9 a.m. Monday morning found father and daughter bound for Lake Washington in an entourage of VIPs that included Washington Territorial Governor Watson Squire (1836-1926) and former governor Elisha Ferry (1825-1895). They toured the lake on the steamer Bee, watched by numbers of "blooming damsels of Lake Washington ... gathered along the banks" (The Seattle Daily Times, August 24, 1886). The party stopped occasionally along the lake to visit fruit orchards and farm houses. At the end of their Lake Washington tour they walked across the Montlake portage to Lake Union and took another steamer tour. "On the whole a very pleasant day was passed, [and] the party seemed delighted with their trip," reported the Post-Intelligencer ("Visit to the Lakes").

Loyal Sentiments and Marching Tunes

On Tuesday, August 24, Sherman attended a G.A.R. meeting and reception at the Odd Fellow’s Hall, and gave a short speech "replete with loyal sentiments" (The Seattle Daily Times, August 25, 1886). Wednesday was marked by a large gathering, called a camp fire, of the G.A.R. at Brown’s Pavilion that evening. It was a rousing affair, and full of dignitaries: Sherman, Union General John Logan (1826-1886) -- regarded by many as the founder of Memorial Day -- Governor Squire, ex-Governor Ferry, and Michigan Governor Russell Alger (1836-1907).

The band played marching tunes as people streamed by the dignitaries' platform and shook the hands of both generals. Speeches and toasts followed a dinner of pork and beans and hard tack and coffee. Sherman gave a 25-minute speech, "full of witty and telling allusions" (The Seattle Daily Times, August 26, 1886). But both the Times and the Post-Intelligencer gave more coverage to Logan’s speech, particularly since he spoke in favor of statehood for Washington Territory (which would occur three years later). The camp fire concluded at 11:30 p.m. with three cheers for the old generals.

This Was A Real Nice Clambake

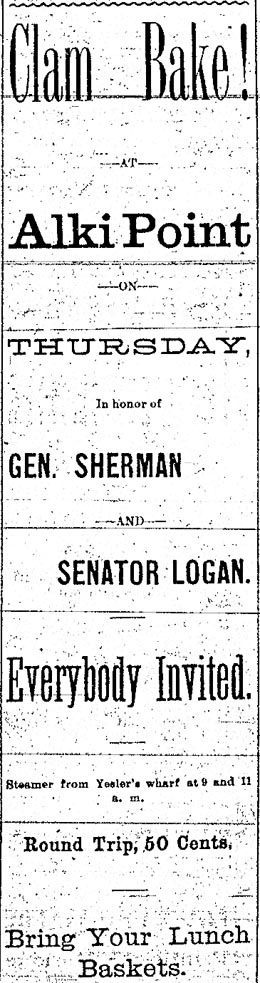

But it was Thursday that may have been the most memorable day. There was a clambake and basket picnic at Alki Point. Ads announcing the event appeared in the Times with the note "everybody invited," and hundreds happily accepted the invitation. Steamers began leaving Yesler’s Wharf at 9 a.m. and ran all day; others took small boats, and by noon there were at least 600 people at the clambake.

And what a treat it was. Salmon and clams were roasted on rocks that had been heated with a fire of cedar branches, and the seafood was covered with burlap and a thick mat of damp seaweed in order to trap the heat and ensure a thorough bake. After the feast Sherman and Logan spent more than an hour giving autographs on the insides of the empty clam shells. By and by ex-Governor Ferry called for a dance and for about an hour the picnickers waltzed to tunes furnished by Professor Vaughn’s orchestra. At 4 p.m. the festivities wound down and the crowd returned to Seattle.

Sherman left Seattle on Friday morning, August 27, bound for Victoria, British Columbia. He left behind thousands of thrilled Western Washingtonians (some of whom had come from as far as Whatcom County to see the general). Years later, they were still reminiscing about his visit.