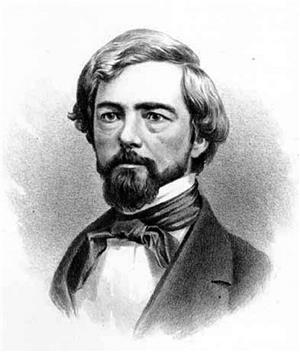

On April 12, 1861, former Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), the delegate to the U.S. Congress for Washington Territory, returns to the Northwest after an absence of 19 months spent attending Congress in Washington, D.C. Stevens has come back to Washington Territory to run for reelection to a third term as territorial delegate.

Returning to Controversy

During his tenure in the nation's capital, Stevens had successfully lobbied Congress to pass several pieces of legislation beneficial to the citizens of Washington Territory, and he felt confident that he would be nominated as the Democratic candidate and win reelection in the predominantly Democratic region.

Upon his arrival in the territory, however, he discovered unexpected opposition. Some influential Democrats resented his 1860 activities in support of John Breckinridge (1821-1875) instead of Stephen A. Douglas (1813-1861) for the Democratic presidential nomination. In addition, a vocal faction of his political enemies had spread rumors that he had defaulted on his debts as Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs, that he was a secessionist, and that he was in favor of the formation of an independent republic of Pacific states.

By coincidence, the charge of debt default was put to rest on the day of Stevens's arrival in the territory by the publication of letters from the Treasury Department in Washington, D.C., declaring that in fact the government owed Stevens more than $200. "So much for the attempts of party malice to ruin the private character of an estimable citizen and faithful public officer" remarked an Olympia newsman ("Gov. Stevens").

On the Union Side

Stevens immediately began a vigorous campaign to defend his record, assert his commitment to the Union, and galvanize his supporters. Within 48 hours of disembarking, he spoke at Vancouver, then traveled upriver to Walla Walla before making his way to Olympia on April 28. The editor of the Olympia Pioneer and Democrat, a supporter of the former governor, wrote:

"We welcome him, as one who has served us diligently, with great energy and ability, as one who has done more for Washington Territory than any other one man within its borders, in developing its resources, encouraging enterprise, and in every way making our country and people known privately and publicly. In the Congress of the United States he ranked at par with the soldier, the scholar, the statesman, or the man of science. Unjust aspersions and malicious slanders, manufactured for particular purposes, have been used against him whilst absent, but, arrived at home, he has had an opportunity to defend himself, and in doing so, has gained many new friends whist he strengthens the attachments of those who are old and tried" ("Arrival of Gov. Stevens").

Political Maneuvering

By the time the Democratic nominating convention opened in Vancouver on May 13, Stevens was convinced that he had more than enough committed votes from the elected delegates to win the nomination. But he had not counted on a tactical maneuver by his opponents to disallow proxy votes from delegates who were not attending the convention in person but had entrusted their votes to other delegates, a practice that had always been permitted in the past. Because a significant number of his delegates lived east of the Cascades and had not made the trip to Vancouver, "this decision virtually ended Stevens's chances for nomination" (Richards, 356).

According to his son Hazard (1842-1918), Isaac Stevens was "indignant at such unworthy treatment at the hands of the party he had served so faithfully and well … and at once withdrew his name as a candidate" (Stevens, 314).

After Selucius Garfielde (1822-1881) was finally selected on the twenty-fifth ballot, one of the conventioneers moved that Stevens be asked to address the convention, and the motion was carried unanimously. "The Governor was greeted with uproarious applause and made a stirring speech of some length" in which he pledged his support to the party and their platform (Proceedings). After addressing the crisis facing the nation, he closed:

"Fellow citizens and fellow Democrats, I am profoundly grateful for the confidence which, during eight long years of labor, you have placed in me ... . My own views and opinions are known to you. I have nothing to explain, to retract, or to apologize for. I have sought faithfully, under all circumstances, to do my duty. I feel that at my hands the honor of the Territory has been sustained, and I can look every man in the face, knowing, as I do, that I have done no man intentional justice" (Stevens, 316).

Immediately thereafter Stevens returned to the East to serve as a military leader on the Union side in the newly declared Civil War. After fighting in the war for a year and some months, and after being promoted twice, Major General Stevens was killed in September 1862 in the Battle of Chantilly.