On April 12, 1861, forces of the Confederate States of America shell the Union Army-held Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, setting off the bloody Civil War that will not end until almost exactly four years later. The war will eventually claim more than 600,000 lives, including that of Washington's first territorial governor, and leave more than 375,000 wounded. With the exception of a few casualties, the war has little immediate or direct effect on Washington Territory, which is far from the battlefields and officially slave-free.

The Road to War

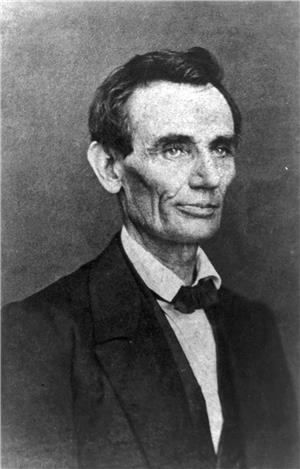

Enslavement of Africans had been an issue since the founding of the republic in the late eighteenth century, with the economy of the Southern states dependent on the use of slaves and the more industrialized northern states being largely slave-free. The simmering debate flared on occasion in the decades before the Civil War, often around such issues as whether new territories in the West should be "slave or free" and whether slaves who managed to escape to non-slave-holding states should be allowed to keep their freedom. There was no national consensus on the issues, but the abolitionist cause was gaining strength year by year, and time was clearly running out for what had become known as the "peculiar institution" of slavery. It was the election of Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) as president in 1860 that brought matters to a full boil.

Lincoln was known to be anti-slavery, and although he had not promised during his campaign to outlaw the practice (and in fact pledged to not interfere in the affairs of the then-slave-holding states), the South nonetheless saw his election as a direct threat to their economic and cultural survival. On December 20, 1860, well more than two months before Lincoln was to be inaugurated, a state-wide convention in South Carolina voted to secede from the Union. It was followed in short order by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. Four additional states -- Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina -- were to secede in the coming months, making a total of 11 "Confederate States of America."

The first shots were fired in the first state to vote for secession. Fort Sumter was one of several fortresses ringing the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. After the state's secession, it demanded that all facilities of the U.S. military located in and around Charleston be ceded to state control. Rather than do so, the area commander, Major Robert Anderson (1895-1871), evacuated his forces to Fort Sumter. The subsequent shelling of the fort by the artillery batteries surrounding the harbor on April 12, 1861, forced Anderson to surrender a day later. The Battle of Fort Sumter officially started the United States Civil War, which was to rage for four years and would be the most deadly conflict by far in United States' history.

Sitting it Out, or Nearly So

News of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter was slow to reach the Northwest. Olympia's Pioneer and Democrat on Friday, May 3, 1861, reported only rumors of an impending attack on Fort Sumter, this about three weeks after the war's start and more than two weeks after that fact was known in San Francisco. By its next edition, on May 10, it knew that the war had in fact begun. There were no newspapers in Seattle yet, and reports of the hostilities would have taken several more days to reach there by word of mouth.

In Washington Territory, the Indian Wars were a recent memory, and life on the frontier could still be harsh and difficult. The first cities had just started to rise, but the population of incoming settlers remained largely rural and remote. The territory was reachable only by extended sea voyage or arduous overland trek. The telegraph had not yet arrived and a national rail link to the territory was years away. People were fully occupied building their lives in a new land, and it is fair to say that there was no patriotic rush to arms in support of either side in the Civil War by the vast majority of settlers in Washington Territory.

Nor was slavery a burning issue in the Northwest. The 1860 federal census found just 26 black males and four black females in Washington Territory, and no slaves. But even though both the state of Oregon and the territory were officially "slave-free," there was in fact a small handful who had been brought west by their "owners." There were only two verified black slaves in Washington Territory in 1860 -- a boy in Olympia and a woman at Fort Steilacoom -- and none by the war's start in 1861. The last of these, the boy belonging to James Tilton (1820-1878), surveyor-general of the territory, had fled to refuge in Victoria, Canada in 1860.

The official slave-free status and virtual absence of slaves did not translate into wide abolitionist sentiment in Washington Territory, however. Territorial politics were dominated by the Democratic party, not by Lincoln's Republicans, and most early historians of the region reported that public sentiment at the start of the war, to the extent it could be divined, was against interference in the affairs of the Southern states. A rather typical view of the situation is set forth in History of Washington, The Rise and Progress of an American State, by Clinton A. Snowden:

"They had long heard of the threats made by the secessionists to break up the Union, but did not regard them as serious. They were so far away that only the last and feeblest reverberations of the guns from Fort Sumpter (sic) reached them. The blare of trumpet, and soul-stirring throb of drum, that sounded so continually in the ears of people in the Eastern States, hardly penetrated to their quiet homes, and when they did it hardly seemed probable that any patriotic response on their part, if made, could be of any benefit.

The Democrats had always been in the majority in the territory. All the governors so far had been Democrats, appointed by Democratic presidents, and all the delegates in Congress had been Democrats, and had been elected by considerable majorities. The majority had, therefore, long been opposed to any interference with slavery, and inclined to sympathize with the slaveholders, as against the abolitionists ... . The majority accordingly were but little inclined to march across the continent to engage in the war on either side, and the minority probably did not, for some time, comprehend that the attack on Sumpter had changed the issue from one about slavery, to one about union or disunion" (Snowden, Vol. 4, 103-104).

The Volunteers

Far though it was from the battlefields of the Civil War, Washington Territory was not entirely untouched by or unconnected to the conflict. Famed Union generals Ulysses S. Grant and Philip Sheridan were just two of the prominent Union commanders who had spent time in Washington Territory in the 1850s, as had General George Pickett of the Confederacy. U.S. Army units that had served in the Indian Wars and the San Juan Pig War of 1859-1860 (in which the only casualty was the pig) were called back to fight the Confederacy. They were replaced by a relative handful of volunteers, and it would be nearly four decades before the national military returned to Washington, by that time a state, in numbers approaching the pre-Civil War years.

A Union recruiter, Colonel Justus Steinberger, came to the Northwest in early 1862, but found few volunteers and received little official encouragement. Resolutions of support for the Northern cause were introduced in both houses of the Territorial legislature, but did not pass. Steinberger moved on to California and eventually managed to raise a regiment of volunteers, known as the First Washington Volunteer Infantry, even though only two of its 10 companies were recruited from north of California, and one of those was comprised primarily of men from the state of Oregon. Only a single unit, Company K, was made up exclusively of men from Washington Territory. This company rarely left Fort Steilacoom, and none of the regiment ever got farther east than Idaho.

The Conscripts

The difficulties that the Union cause had in recruiting volunteers led to the passage of the Conscription Act in March 1863, which called for the enlistment in military service of all able-bodied males between 20 and 45 years of age for terms of three years. This initially was greeted in Washington Territory with even less enthusiasm than Steinberger's efforts to recruit volunteers. Again, from Snowden:

"The enrolling officers appointed under the conscription act in 1863, to make up the lists of able-bodied men subject to military duty, met with some trouble, as they did everywhere else. The provost marshal established his headquarters at Vancouver, and special deputies were appointed in all the counties. Edwin Eells, who served in Walla Walla County, probably met with as much resistance in the discharge of his duty as any of them. The lawless element, which had been attracted to that part of the territory by the successive gold discoveries, was still strong in the community, and it was not patriotic in any sense. It became openly defiant when it began to be known that it would be compelled to furnish its share of recruits for the army in case of need. In one saloon a bucket of water was thrown over the enrolling officer; in another a bunch of firecrackers was set off under his chair, as soon as he began to write, and in another all his books and papers were taken away and destroyed" (Snowden, Vol. 4, 112).

Slowly, however, sympathy for the Union cause grew in Washington Territory. Women seemed particularly patriotic, and it was said that, in proportion to population, "they led every State and Territory in the Union in sending supplies for the comfort of the soldiers" ("Washington Territory in the War Between the States," p. 39). But the war was being fought on battlefields far away, and the only Confederate threat to the territory was the odd privateer roaming the waters of the North Pacific.

Nonetheless, men from Washington Territory did fight, on both sides, and given the region's small population at the time, the contribution cannot be deemed wholly insignificant. In fact, the territory's first governor, Isaac Stevens, was an early volunteer to the Union cause and was killed at the Battle of Chantilly in September 1862 after surviving the second Battle of Manassas (Bull Run) a month earlier. But compared to the calamitous effects that the war had in the East and South, the sacrifices of the West were minor indeed.

Remembrance of War and Sacrifice

The war would rage for almost exactly four years, ending only when General Robert E. Lee (1807-1870) surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox Courthouse on Palm Sunday, April 9, 1865. The vastly outnumbered South had won its share of battles, but was eventually overwhelmed by the numbers and might of the Union forces. Six days after Lee's surrender, John Wilkes Booth (1838-1865) assassinated President Lincoln, a tragic coda to a tragic era in the nation's history.

The memory of the war lived on in Washington Territory, and then in Washington state, in perhaps greater measure than the actual contributions made by its citizens. In Seattle, Stevens Post No. 1 of the Grand Army of the Republic was established in 1878, the largest of nearly 100 such posts in the Washington Territory organized by veterans of the Union side. It began the tradition of an annual Memorial Day observance in Seattle the following year. In 1895, David (1833-1912) and Hulda (1829-1906) Kauffman donated land on Capitol Hill adjacent to Lake View Cemetery to local chapters of the GAR for the establishment of a cemetery for Union veterans. The site fell into disrepair over the years, but between 1997 and 2002 it was rehabilitated by a volunteer group, Friends of GAR, and is still in use today.

A Washington chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans was established in 1904 and exists today. The Robert E. Lee Chapter No. 885 of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was started in Seattle in 1905 for the stated purpose of providing "care to the Confederate Veterans and their families"("History," UDC website). In 1926, the group erected a monument in Lake View Cemetery in memory of "United Confederate Veterans." Although later vandalized of its bronze decorations, it remains there today, and the UDC is still an active organization.

Aftermath

Scholars disagree to this day about whether the Civil War primarily was fought to rid the country of slavery or to preserve the Union. Regardless, the outcome achieved both goals. The 1860 census had counted over 3,200,000 slaves in America; the 1870 census counted none. The attempt by the Confederacy to create two nations from one was defeated, and the Union reconstituted intact.

Although Washington Territory was far removed from the scenes of battle and suffered no great loss of life or property, it cannot be said that it was unaffected by the war. The entire nation was affected, and in fact transformed, by the defeat of secession and the freeing of millions of its citizens from bondage.