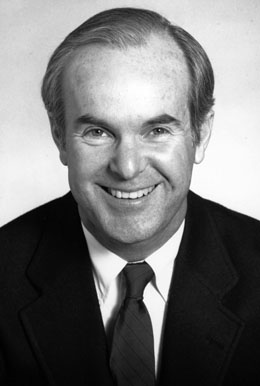

Booth Gardner, Washington’s charismatic 19th governor, was a collection of complex contradictions. He exuded genuine warmth while dogged by demons. A privileged childhood was pockmarked by emotional abuse, divorce, and the death of his mother and sister in a plane crash. The wealth and encouragement of his powerful stepfather, Norton Clapp (1906-1995), empowered Gardner to become his own man and helped propel him to political power. As a student at the University of Washington in the 1950s, Gardner began a lifetime of volunteer work with the underprivileged. After receiving an MBA from Harvard, he became a university administrator and businessman. From a successful stint as Pierce County’s first executive, he emerged from “Booth Who?” obscurity to be elected governor in 1984. Rated one of the top three in the U.S. in 1991, Gardner was his own harshest critic, frustrated when politics thwarted his goals. Gardner clearly could have had a third term, but instead became U.S. trade ambassador in Geneva. There the malaise that had descended during his second term was diagnosed as Parkinson’s disease. Returning to Tacoma, he endowed a Parkinson’s care center and in 2008 led the campaign that saw Washington become the second state in the nation to allow "Death with Dignity." Booth Gardner died on March 16, 2013.

Pioneer Roots, Troubled Branches

The Booths and Gardners were Northwest pioneers. In 1843, the governor’s ancestors cast key votes to create the Oregon Territory and helped write its constitution. Manville Booth, the governor’s great-grandfather, was King County auditor from 1875 to 1881. His grandfather, William Gardner Jr., founded a plumbing and heating business in Tacoma that became one of the largest in the Northwest. In 1933, the governor’s beautiful mother, Evelyn Beatrice Booth (1912-1951), married Bryson "Brick" Gardner (1906-1966), a University of Washington business school graduate. She was a Catholic, he an indifferent Presbyterian. Alcohol, however, was the problem that soon had the marriage on the rocks. “Brick” Gardner was a raffish redhead whose personality turned abusive when he drank, which was often. The Gardners became young socialites in Tacoma. They were living beyond the means of Brick’s job as sales manager for a chemical company (Hughes, 27-28).

Washington’s future governor was born in Tacoma on August 21, 1936. After some indecision over a first name, he was finally christened William Booth Gardner. Always called Booth, he was popular with his classmates because he was funny and nice, not because he seemed to be well off. A number of his classmates were also from well-to-do families. And many of them, like Gardner, knew that “Behind those stone fences, down those long, forested driveways” and inside those stately homes there were dysfunctional adults and children suffering from the fallout (Hatch). A stand-out athlete as a youth, Gardner has always said his life has been a series of “curve balls,” and God judges us on how we step up to the bat.

Gardner’s sister, Gail (1937-1951), born in 1937, suffered from epilepsy. “She was sick all the time,” he recalls. “I never got close to her. I just disliked her because she got all of the attention. I’d do things to torment her and then I’d get in trouble” (Hughes, 31). Evelyn intimated to friends that life at home was becoming unbearable. Then she met Norton Clapp, an heir to the Weyerhaeuser timber fortune. Clapp had shrewdly parlayed his inheritance into an even larger fortune, which he resolved early on to share with the less fortunate. Clapp founded the Medina Foundation, one of the Northwest’s leading philanthropies.

The Gardner and Clapp divorces and immediate nuptials were front-page news in 1941. Evelyn was granted custody of Gail, 3, and Booth, 4½ “until he is 6, when custody will go to his father.” During the Clapps’ honeymoon, Booth and his sister went to Wenatchee to stay with their Aunt Lou and Uncle Ed. “That boy cried and cried on the train,” Lou Booth recalled years later. "He just kept sobbing, 'I want to go home to C Street [in Tacoma]' " (Hatch).

Brick Gardner was devastated by the divorce but managed to retain custody of Booth. Gail went to Seattle to live with her mother, her stepfather, and Clapp’s sons from his first marriage. During World War II when Brick was in the South Pacific as a naval officer, Booth lived with his mother and stepfather. By war’s end, Gardner was back with his father and a kindly yet hapless stepmother, Mildred McMahon Blethen. He had a new step-sister, spunky Joan Blethen.

Brick was now the sales manager for Tacoma’s Cadillac dealer. Their handsome home was soon in upheaval. Brick and “Millie” were both alcoholics. Booze transformed Brick into an “overgrown child with a mean and destructive streak. Dressed in a silk suit and seated behind the wheel of a silver Cadillac, he played the part of a wealthy rogue -- even while he ridiculed the rich” (Hatch). His son ended up on the receiving end of his sarcastic digs. Booth and Joan bonded in the chaos. “He got more gregarious. He was doing well in school, and he did well in track,” she recalls. “He came out a very serious, very hard-working young man who was also charming” (Hughes, 38-39).

Tragedy and an Epiphany

During spring vacation in 1951, 14-year-old Booth went skiing with his mother. “It was the happiest time of my life” (Hughes, 46). Its duration was tragically short. When they arrived back home, Evelyn learned that one of her orchids was the sweepstakes winner in a prestigious show. En route to California to accept the trophy, Booth’s mother and his 13-year-old sister died when an airliner slammed into a hillside, killing all aboard. “That event had a greater effect on me than anything else in my life, before or after,” Gardner says. “I felt alone in the world and I felt that I was somehow responsible for all of this” (Hughes, 48). He was never really comfortable with the sizable trust-fund inheritance he received when he turned 25. But it did allow him to follow Norton Clapp’s example and help the less fortunate.

Clapp, grieving himself and filled with empathy for his stepson, summoned the youth to his office a few weeks after the funerals. He told Booth that Evelyn was the love of his life. “If you ever get in trouble, call me.” They’d never been close, but Booth now saw Clapp as his role model. “That’s when I started really thinking big” (Hughes, 51).

In the fall of 1954, Gardner enrolled at the University of Washington, boarding with his aunt and uncle. Despite his sunny disposition, he seemed rudderless. An exponent of tough love, Aunt Lou prodded him to get off the sofa and apply for an after-school job with the Parks Department. He began working at playfields in the largely African American Central District as a coach, tutor and big brother. It was an epiphany. “Prejudice just went right over my head ... . I saw kids with severe disabilities and met their brave and frustrated parents. ... Even though I thought I’d been pretty much hammered as a kid, they had it a lot worse. ... I settled down in school and started to work hard because I realized I couldn’t get to my goal if I didn’t get out of college. I wanted to make a difference” (Hughes, 60).

Gardner soon emerged as a big man on campus. Still, he had no steady girl until he met a stunning cheerleader, Jean Forstrom (b. 1938). During his senior year, she worked on his winning campaign for first vice-president of the student body. Married on July 30, 1960, they moved to Boston where he entered Harvard Business School.

When he turned 25 in 1962, Gardner inherited a trust fund estimated at $1.7 million, which grew steadily over the years. His frugality is a running joke among friends, yet it has a serious side. When she was First Lady, Jean Gardner told a reporter, “He always felt uncomfortable in fancy clothes, fancy cars or whatever. I really don’t know why. Maybe he felt guilty” about inheriting a fortune in the wake of his mother’s death (Hatch).

Gardner became a father not long before he lost his own. Doug Gardner was born in 1962, Gail -- named after Booth’s sister -- in 1963. After receiving his MBA, Gardner was working as an executive with a clothing manufacturer in Tacoma. Brick Gardner, 60, was living in Honolulu, still fighting a losing battle with alcohol. In a drunken misadventure, he fell to his death from the ninth floor of a hotel.

Stepping Stones

After a stint as assistant to the dean of Harvard Business School, Gardner returned to Tacoma in 1967 to head the Business School at the University of Puget Sound. He decided the legislature was the best stepping stone to becoming governor. He filed as a Democrat to take on Larry Faulk, an ambitious young Republican seeking re-election to the State Senate. Clearly the underdog, Gardner cribbed from Faulk’s own campaign handbook, dramatically outspent him, and captured 56 percent of the vote. In a few years they would have a rematch for higher stakes.

Blessed with wealth, a keen intellect, and a winning personality, Senator Gardner, 34, arrived in Olympia to considerable fanfare. By most accounts, however, including his own, Gardner’s legislative career was checkered -- if not without chutzpah. He irritated leadership in both parties by backing a bill to place the legislature under the Open Public Meetings Act. He also refused to sign any bill the first day he saw it. Asked in 2009 to cite his most notable achievement as a state senator, Gardner declared, “None. Nothing. ... I love the administrative aspect of government. I tolerated the legislative aspect of government” (Hughes, 84).

When Clapp greased the skids, Gardner resigned from the Senate in 1973 to become president of the Laird Norton Company, which owned lumberyards, prime real estate, shopping centers, and industrial parks, plus a major stake in the Weyerhaeuser Co. But the job took its toll on his marriage. Commuting from Tacoma to Seattle and working 12-hour days, Gardner struggled to meet his family responsibilities. Years later, his son told a New York Times reporter, “He provided for us, but he wasn’t there for us” (Bergner). Jean resented Booth’s bouts of withdrawal. His work and his civic causes seemed to be a higher priority than his family.

New Charter, Old Foe

Weary of cronyism and scandal, Pierce County voters in 1980 approved a new charter that created a County Council headed by an elected executive. Faulk, who helped shape the charter, promptly filed for county executive. So did Booth. The Gardner campaign flooded the newspapers and airwaves with arresting ads that stressed Booth’s management moxie and dedication to public service. Faulk fought back with hard-hitting ads of his own. “The last time the people elected Booth Gardner to office,” one declared, “he walked out on them.” Faulk was closing the gap down the stretch but badly outspent.

On March 10, 1981, Gardner was elected Pierce County’s first county executive, winning 52.8 percent of the vote. Gardner had told the Tacoma News Tribune’s editorial board he had no plans to run for governor in 1984. But the paper polled a lot of Democrats who thought otherwise. “If Booth isn’t thinking about it, there’s a lot of people around here thinking about it for him,” one said (Pugnetti).

“Being Pierce County Executive was the best job I’ve ever had,” Gardner says. “It was the size where I could get to know everybody I worked for and with” (Hughes, 102). Those who hadn’t worked with him before were immediately impressed by his remarkable memory and ability to focus on the most important details. Working long hours, he seemed to be everywhere -- buttonholing citizens outside burger joints and spending a day with the county road crew replacing Stop signs. He fielded a talented team of assistants. Together, they streamlined county operations, cut costs, improved productivity, and instituted better customer service. “I think Booth did a great job because he brought in a whole new way of thinking,” Faulk said in 2009 (Hughes, 112).

Spellman in Trouble

By the spring of 1983, Governor John Spellman, a moderate Republican, was reeling from a brutal recession and the intransigence of conservatives in his own party. As Gardner geared up to challenge him, Peter Callaghan, a young reporter for the Everett Herald, wrote one of the most-quoted Gardner profiles. Many would copy his observation that Gardner looked “like a cross between Bob Newhart and Tommy Smothers: preppy but likeable.” Still, the lines that drew the most attention were these: “He voluntarily walked into a government best known for its corruption, mismanagement and patronage. In the spring of 1981, Pierce County was $4.7 million in the red. By the end of this year, Gardner expects a surplus of $1 million ... . Even his most vocal critics concede he’s a master administrator” (Callaghan).

Ron Dotzauer, Gardner’s free-wheeling campaign manager, focused on Booth’s business background: “He did it in Pierce County and he can do it for the state.” The masterstroke was a full-court press to answer the question practically everyone outside of Tacoma was asking: “Who is Booth Gardner?” Soon “Booth Who?” was festooned on thousands of buttons.

Dotzauer knew that beating State Senator Jim McDermott, Gardner’s battle-tested opponent in the Democratic primary, would be harder than ousting Spellman. Visibly nervous, Gardner stumbled badly in their first debate. One wag observed that his voice was like “Elmer Fudd on helium” (Hughes, 123). Humiliated, Gardner found his competitive juices kicking in. He shellacked McDermott and set out against Spellman with a lead some polls pegged as high as 20 points. The governor’s image was that of a pipe-puffing, Gerald Fordish nice guy. Spellman was in fact a skilled debater with a track record for making tough decisions. What ensued was one of the hardest-hitting campaigns the state had ever seen. The Spellman campaign over-reached, perhaps fatally, in branding Gardner “a shill for big labor,” which energized a key Democratic constituency. The teachers’ union was impressed by Gardner’s pledge to be “The Education Governor.” On November 6, 1984, with 53.3 percent of the vote, Booth Gardner was elected governor.

Ambitious Goals

One of Gardner’s top priorities was to develop a diversified, cutting-edge economy. In the meantime, services necessary to help the needy had to be sustained and “the practice of pushing our problems into the future and onto the shoulders of our children” must end, he said in his inaugural address. He couldn’t solve the state’s myriad problems without the help of the legislature, he emphasized. “Never has it been more essential for state government to be united” (State Library). For Gardner, nothing had ever been more frustrating than trying to make that a reality over the next eight years.

Gardner’s cabinet had a bipartisan flavor. It was a blend of management expertise and Olympia moxie. Richard A. Davis, an executive with Pacific Northwest Bell, was commissioned to unravel a rat’s nest of problems at the Department of Labor and Industries. John Anderson was wooed away from Oregon to lead Gardner’s “Team Washington” economic development effort. The appointment of Bellevue City Manager Andrea Beatty to head the Department of Ecology was controversial. She proved to be a hard-nosed advocate. Her successor in 1988 was Christine Gregoire, an intensely bright deputy attorney general. Gregoire had worked on the implementation of “comparable worth” pay hikes for some 15,000 mostly female state workers who had prevailed in a landmark sex-discrimination case. Placing capable women in important posts was one of the hallmarks of the Gardner administration.

With the economy beginning to rebound, teachers, troopers, and other public employees demanded salary increases. Environmentalists, educational reformers, and mental-health advocates also wanted action. Yet revenues were still lagging far behind the cumulative wish list. Washington’s tax system was heavily dependent on consumer spending. Sales and business and occupation taxes being highly sensitive to economic downturns, state government was balancing its budget on a two-legged stool. Dan Evans, the three-term governor Gardner admired, had little success in repeated attempts to convince the voters an income tax was the best solution. Gardner believed, however, that if he could “restore trust in government” tax reform was “doable” (Hughes, 145). Seven years later it still wasn’t.

Gardner’s first term was a crash course in practical politics. He warned early on that the state could face a deficit unless spending was trimmed. The lack of followership left him disillusioned. The governor recharged his batteries by visiting classrooms around the state. While teachers were disgruntled, kids greeted him like a movie star. When he was jogging, passersby honked and waved. Dick Larsen, The Seattle Times columnist who dubbed him “Prince Faintheart,” conceded that Gardner’s popularity ranked “somewhere between Donald Duck and fresh-baked bread” (Larsen).

Gardner celebrated progress on several fronts: an ambitious construction budget for schools, colleges, prisons, parks, and hatcheries, and measures to expedite cleaning up Puget Sound. For the second year in a row there would be no workers’ compensation rate increase. The push for standards-based education, one of Gardner’s highest priorities, began with legislation requiring achievement tests for all high school sophomores and more strenuous graduation requirements. Gardner, meantime, also issued an executive order banning discrimination against gays and lesbians in state employment. He made more history when he named Charles Z. Smith (b. 1927) to the Washington State Supreme Court. Born in the segregated South in 1927, Smith was the court’s first ethnic minority. Gardner signed a Centennial Accord with the tribes, pledging the state to a more formal collaborative relationship to solve natural resources issues without litigation. The latter-day treaty was the first of its kind in the U.S. It became an international model.

Gardner's Second Term

Gardner won a second term in a waltz in 1988, crushing State Representative Bob Williams, a feisty Republican accountant from Longview who had no answer for Gardner’s charisma or war chest. Gardner’s second inaugural address, “The Centennial Challenge,” was capitalism with a conscience in a shrinking, high-tech world. “We stand on the threshold of a new century of statehood,” he said. The choices were clear: “Either we respond to international competition or we doom ourselves and our children to a dramatic slide to second-rate status in the world.” In addition to the moral commitment to create a fair and just society, “we now have an economic imperative to help our people become well educated, productive citizens” (State Library).

Denny Heck, a hard-charging former legislative leader, became Gardner’s righthand man for the rest of his tenure as governor. The Gardner tax reform team -- Heck, Dean Foster, and Bill Wilkerson -- pushed hard over the next four years for the lawmakers to send a tax reform plan to the voters. But to no avail. The legislature did approve Gardner’s plan to retain and broaden the reach of the Puget Sound Water Quality Authority and create a Department of Health.

When the spotted owl crisis devastated timber communities, Gardner created a special team to coordinate assistance programs, including wide-ranging efforts to help rural communities diversify their economies and retrain workers. This time, the governor found many allies in the legislature. It provided funds for worker retraining and economic development.

The 1990 legislature approved Gardner’s “Learning by Choice” plan. It mandated open enrollment and Running Start, one of the most effective advanced-placement programs in the nation. Bright high school juniors and seniors may attend community colleges full- or part-time for free. During his last two years as governor, Gardner was chairman of the National Governors Association and emerged as a national leader in education reform. A strong advocate of student testing, he nevertheless warned, “You can’t just raise the bar and say every child must reach it.” The dropout rates would soar and teachers could end up “just teaching to the test” (Hughes, 222). In the years to come, as the controversial Washington Assessment of Student Learning -- the WASL -- was instituted, he regretted not making that point even more forcefully.

On October 22, 1991, reporters were summoned to an unexpected press conference. With his wife at his side, Gardner announced he was “out of gas” (Ammons). Jean had made it clear that their marriage likely wouldn’t survive another term. Looking back, Gardner believes his fatigue, depression, and indecisiveness were early symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

The Tin Man

Gardner accepted a Clinton appointment as U.S. ambassador to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in Geneva, duly warned that tedium was its middle name. “When I got there they were talking about bananas,” Gardner says ruefully. “And when I left they were talking about bananas” (Hughes, 233). When he got there he was also alone. Jean stayed behind. He found it hard to focus on reams of paperwork. When he went skiing, he was disconcerted that he couldn’t make right turns. He felt “like the Tin Man” in The Wizard of Oz. An English-speaking doctor quickly diagnosed the problem: Parkinson’s. The revelation struck him as a living nightmare: “I was afraid I’d be a stumbling, stuttering, blank-eyed, stiff-legged human train wreck ... ” (Hughes, 235). On the other hand, maybe he’d be lucky. Researchers were exploring new treatments. He met an attractive young woman from Texas who was vacationing in Europe. Cynthia Perkins (b. 1959) was 23 years his junior. She gave him his verve back. In helping himself, he could help thousands of others, maybe even find a cure. What a legacy that would be, he told himself.

Gardner came home in 1997. A new drug dramatically alleviated symptoms of the disease. The Booth Gardner Parkinson’s Care Center opened in 2000 in Kirkland. He mingled with doctors and patients, took up golf, and returned to the Central District to boost athletic programs and tutor kids. In 2001, the Gardners’ 40-year marriage ended in divorce. Booth immediately married Perkins.

Within three years, the disease was winning again. His ebullient voice was frequently reduced to a raspy whisper. In 2006, at a gala for TVW, Washington’s version of C-Span, Gardner announced he would soon undergo a new deep-brain surgery. “I’m guaranteed five good years of life at half the medication if I survive it -- and I will survive it!” The room erupted. What came next was more controversial. He was going to lead an initiative campaign for “Death with Dignity,” a law that would allow the terminally ill to receive assistance to end their lives on their own terms. “It will be my last campaign” (TVW).

The deep-brain surgeries -- especially the second -- were a huge success for a while. But inexorably, the symptoms returned. Gardner and Perkins separated during the stressful campaign for the initiative. They would divorce but remain good friends. Gardner’s son Doug, a born-again Christian, was appalled by the campaign. “We don’t need Booth and Dr. Kevorkian pushing death on us. Dad’s lost. He’s playing God, trying to usurp God’s authority ... . I fear the day when he meets his maker” (Oregonian).

Initiative 1000 easily made the ballot. With contributions totaling nearly $800,000 by Gardner, friends and family, it also handily won the fundraising race. Opponents, including Martin Sheen, the noted actor, branded the plan “a monstrously selfish act” (Hughes, 262). Nearly 58 percent of the voters disagreed. On November 4, 2008, Washington became the second state in the nation to allow assisted suicide. This “is a testament to our belief that individuals can make a difference -- that power does indeed reside with the people,” Gardner told cheering supporters (thenewstribune.com).

Dividing his time between a condo in Tacoma, the family compound on Vashon Island, and the Parkinson’s center that bears his name, Gardner continued to battle the disease with pluck, physical therapy, and drugs. A documentary about his last campaign was nominated for an Academy Award in 2010. His biography -- “Booth Who?”-- by the Secretary of State’s Legacy Project, appeared that same year.

Booth Gardner died on March 16, 2013.