On December 31, 1932, medicinal liquor becomes available in Seattle after a 15-year hiatus. A state law that effectively prohibited medicinal liquor had been repealed by Washington voters in November 1932, and though the National Prohibition Act is still in effect at year's end, it makes an exception for medicinal liquor if state law allows it. Seattle rings in 1933 in the wettest, happiest New Year's celebration in years.

Washington Goes Bone-Dry

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries one could buy liquor in the state's drugstores, usually in the patent medicines (which contained as much as 20 percent alcohol) that the stores commonly sold. But when people wanted a drink they generally didn't think of their local drugstore -- that's what saloons were for. That changed when Prohibition took effect in Washington on January 1, 1916, and the saloons disappeared.

At first there was an exception to the new dry law that allowed medicinal liquor to be sold in drugstores under a permit system. Drugstores suddenly became more popular. They began popping up like mushrooms during the rainy season. Between January and March, 1916, 65 new drugstores opened in Seattle alone.

It didn't last. In February 1917 Governor Ernest Lister (1870-1919) signed House Bill 4, otherwise known as the bone-dry law, which tightened restrictions on alcohol in the state. The law still allowed druggists to sell medicinal liquor if they had the required permit, but it prohibited the importation of liquor into the state. Since liquor wasn't manufactured in Washington, this cut off the pipeline for alcohol into the state. Moreover, before the new state law even took effect, Congress passed similar federal legislation known as the Reed-Randall Bone Dry Act. This outlawed the shipment of liquor into any state that had dry laws as of July 1, 1917.

In a futile gesture, opponents of House Bill 4 -- perhaps hoping the federal law would be amended or repealed -- gathered enough votes to call a referendum on the state's bone-dry law. The law appeared on the 1918 ballot as Referendum 10, but voters approved it by a 28-point margin. Ironically, the National Prohibition Act (also known as the Volstead Act), subsequently enacted in January 1920, did allow the importation of medicinal liquor into states that did not have their own laws prohibiting importation. This was a moot point in Washington, and the state stayed bone-dry for another 13 years.

Changed Minds

By 1932 many had changed their minds about Prohibition. All but its most ardent supporters could see it had failed, and restrictions on alcohol began to crumble. In November 1932 Washington voters passed Initiative 61, repealing the state's bone-dry law, with 62 percent of voters favoring repeal. Local ordinances that contained their own liquor restrictions were also quickly repealed, not only in Seattle but in locations as varied as Yakima and Aberdeen. Though national Prohibition was still in effect, it made an exception for medicinal liquor, subject to the restriction that a patient could only be prescribed one pint every 10 days. People soon began needing their medicine.

Tacoma took the honor of becoming the first city in the state to provide medicinal liquor in its drugstores, where it was available by December 17. In Seattle it took a little longer. The repeal of the city's dry ordinance was scheduled to become effective on December 29. But when the big day arrived, there was a problem. The booze was in town, but almost no one could get it in a Seattle drugstore. The problem was with the permits that doctors and druggists were required to have in order to prescribe and sell liquor. They had inundated the Bureau of Industrial Alcohol with so many applications that the bureau was overwhelmed and hadn't approved most of them. Moreover, many doctors hadn't filled out the required questionnaire that accompanied the permit application. Roy C. Lyle, the bureau's supervisor, explained impatiently:

"I'm signing them [permits] as fast as I can. But there is still a great deal of investigational work to be done. Of course, the importance of this medicinal liquor is being exaggerated. It is sold for medicinal purposes only and is not intended for beverage purposes. It can only be sold on doctor's prescription and is not supposed to be authorized by a doctor except for the use of a really sick patient" ("Liquor's Here ... ").

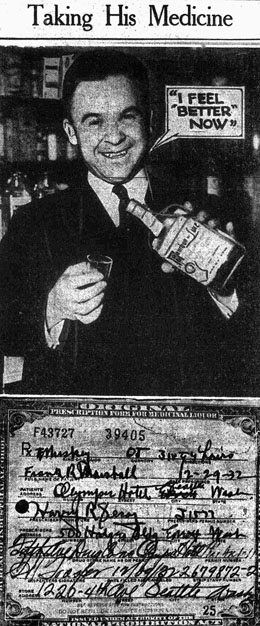

People began getting really sick. Frank Marshall, the assistant manager of the Olympic Hotel, felt so bad on the afternoon of December 29 that he drove to Everett and found a friendly physician who had already acquired the necessary permit. He got a prescription for a pint of Bourbon de Luxe, promptly had it filled, and was soon much improved. He was so delighted that he proudly carried the bottle in his outer coat pocket for all to see. Added the P-I, "Marshall felt a lot better. And he was patiently awaiting the return of his ailment" ("He Buys ...").

Happy New Year!

Most of the rest of Seattle had to suffer for another two days, when finally doctors and druggists all had the permits they needed to issue and fill prescriptions. The timing couldn't have been better: It was Saturday, and New Year's Eve to boot. The number of Seattleites suffering from colds and other maladies surged. People who normally avoided the doctor decided it was time for a visit. Sympathetic doctors had little problem prescribing a pint to their patients, who then rushed en masse to the nearest drugstore. Supervisor Lyle sternly reminded the citizenry that the booze was only to be used for medicinal purposes and opined that it wouldn't be used as a beverage "except by a few thousand people" ("It'll Be Damp…").

That depends on your definition of "few thousand." Whatever the number, it was a happy night in Seattle. Never mind the cold rain and blustery winds that would have otherwise made being out and about miserable. It was party time. The Seattle Times said the sidewalk was so crowded at 4th and Pine that people were walking (and cheering) in the street. Clubs and restaurants were packed; hotels and dance venues were overflowing. The Seattle police, under orders from Chief L. L. Norton to leave casual drinkers alone, obliged and focused instead on drunk drivers and the occasional rowdy pedestrian.

Once medicinal liquor became legal, the remaining restrictions against alcohol toppled like dominoes. Late in March 1933 Congress passed the Celler-Copeland bill, removing the restrictions on the amount of medicinal liquor that a doctor could prescribe, and in April, 3.2 beer became legal. Finally, on December 5, 1933, Prohibition was repealed in its entirety, leaving plenty of folks with tales to tell of their experiences back in the day -- tales that doubtless grew taller after a drink or two.