It's been said that the 98118 ZIP code in Southeast Seattle is the most diverse in the United States. The claim is not quantifiably true, although it's easy enough to believe. Successive waves of newcomers from around the world have found a place for themselves here, beginning with Italians and other people of European heritage in the late nineteenth century; followed by Japanese, Filipinos, and African Americans, among others. The closure of the U.S. naval base in American Samoa led to an influx of Samoans in the 1950s. Thousands of Southeast Asians came in the aftermath of the Vietnam War in the 1970s, joined by Latinos and, more recently, refugees from war and famine in East Africa. The result is what local boosters call a "neighborhood of nations," where Somali children study the Koran a few blocks from the largest Orthodox synagogue in Seattle; fourth-generation Italians and newly arrived South Asians shop at stores owned by second-generation Vietnamese; and Ethiopian wat and Filipino halo-halo are as easy to find as pizza and sushi.

Birth of an Urban Legend

The 98118 ZIP code covers about six square miles, from Genesee and Beacon Hill in the north to Rainier Beach in the south, between Lake Washington on the east and Martin Luther King Boulevard and Interstate 5 on the west. About 45,000 people live within its boundaries, in neighborhoods that range from upscale (Lakewood, Seward Park) to grittier (Hillman City, Rainier Beach).

The idea that this is the most racially and ethnically diverse of all the 43,000 or so ZIP Codes in the country first surfaced about a decade ago. It gained traction in March 2010, when the AOL News website published an article by G. Willow Wilson titled "America’s Most Diverse ZIP Code Shows the Way." Local electronic and print media followed up with their own versions of the story. All reported that the Census Bureau had identified 98118 as the nation’s most diverse. Several later added the qualifier "one of the most," after finding out that the Census Bureau had made no judgment about the comparative diversity of ZIP Codes.

The Census Bureau collects raw data; it does not interpret it. Furthermore, the geographical boundaries that it uses to collect data do not align neatly with those used by the Postal Service to deliver mail. ZIP Codes can cross state, county, census tract, and census block boundaries. They also change frequently, through mergers, splits, and other adjustments. The total number can fluctuate by several thousand every year. "There is no correlation between U.S. Postal Service ZIP Codes and U.S. Census Bureau geography," the bureau points out on its website. The closest approximation is what the bureau calls ZIP Code Tabulation Areas (ZCTAs), which are based on the most frequently occurring five-digit codes in a given area; but these are "generalized representations" and only roughly correspond to actual ZIP Codes.

"We don’t measure whether one zip code is more diverse than another," a Census Bureau media specialist told Seattle writer John Hoole. "People responded to the story because it was so positive. Around here we think of it almost as an urban myth" ("Rainier Valley’s Diversity Myth"). Among those who have accepted it as fact is Washington Senator Maria Cantwell (b. 1958), who welcomed new citizens to "the most diverse ZIP code in the United States" during naturalization ceremonies at the Seattle Center on the Fourth of July 2012 -- repeating remarks she made at the same event in 2011 and at a Seattle University forum on global development in 2010.

Quantifying Diversity

The 2010 census showed that Seattle as a whole is nearly 70 percent white. In contrast, no race or ethnicity can claim a majority in Southeast Seattle. The largest single group in the 98118 ZCTA is Asian (32 percent), followed by non-Hispanic whites (28 percent), and non-Hispanic blacks (25 percent). The numbers vary slightly but the overall picture is the same in a database used by the city of Seattle: 37 percent Asian, 26 percent white, and 24 percent black in five "Community Reporting Areas" for Southeast Seattle (consisting of 12 census tracts and covering a somewhat larger area than the 98118 ZCTA). Both databases show that about 8 percent of the population is Hispanic and about 6 percent is multi-racial.

The census for 2010 included five standard categories of race: white, black, Asian, Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native, plus "some other race." It also collected data on Hispanic or Latino ethnicity; cross-tabulated it with data on race; and offered respondents the option (first introduced in 2000) of identifying themselves as multi-racial. There were 57 possible combinations of two or more racial groups. Respondents also were able to write in their own definition of their race, and one in 14 did so, using such terms as "Arab," "Haitian," and "Mexican." The range of options complicates efforts to decide what particular elements might make one area more "diverse" than another. "There are so many different ways to define diversity," says Diana Canzoneri, demographer and senior policy analyst for the Seattle Planning Commission. "You can pick a formula but when you do, you’re making all sorts of decisions about what counts as diversity" (Canzoneri interview, July 24, 2012).

Canzoneri analyzed ZCTAs in Washington state and nationwide, for HistoryLink, by using the Gini-Simpson Index (also known as the Diversity Index), a mathematical formula which calculates the likelihood that any two people chosen at random in a given geographical area will be of different races or ethnicities. By this measurement, the 98118 ZCTA is the third most diverse in Washington state, after 98178 (covering the Bryn Mawr and Skyway neighborhoods) and 98188 (SeaTac and Tukwila). Out of 17,000 ZCTAs for metropolitan areas nationwide, it’s number 64.

However, there’s more to a story than just statistics. "The numbers just scratch the surface," Canzoneri says. "What people are feeling from their experience, living in an area or visiting an area, can capture so much more than an equation can. It says a ton that people feel it’s such an affirming thing, to live in a diverse neighborhood" (Canzoneri interview, August 3, 2012).

Early Arrivals

The area now within the boundaries of 98118 was originally divided between the Duwamish, who had a settlement at the foot of Beacon Hill; and the Xachua'bsh ("Lake People"), who maintained several long houses along the southern end of Lake Washington (then called Duwamish Lake). A few white settlers moved in during the 1850s, but there was very little other development until 1889, when J. K. Edmiston began building an electric railway from downtown Seattle into the Rainier Valley. Edmiston and his partners bought 40 acres of land near the railway’s first planned station, logged it, cleared it, and laid out streets for what they called Columbia -- today’s Columbia City.

The federal census of 1900 shows that nearly all the 709 people then living in the "Columbia Precinct" were Caucasian. About 20 percent had been born in Washington state or Washington territory; 60 percent had been born elsewhere in the United States; the rest were foreign-born, predominately from Canada, England, Ireland, and Italy. Place names given to newly sprouted neighborhoods reflect the origins of some of the early settlers: Brighton, named after a resort town in England; Beacon Hill, after Boston’s Beacon Hill; Genesee, after Genesee, New York.

Part of the Rainier Valley became known as Garlic Gulch because of the large number of Italians who settled there. Some were "pick and shovel men" -- unskilled laborers -- hired to clear forests and build roads, railroads, and other infrastructure. Others were farmers. Land was cheap, and they found ready markets for their produce in the rapidly growing city of Seattle. Several of these farmers were instrumental in establishing the Pike Place Market in Seattle in 1907.

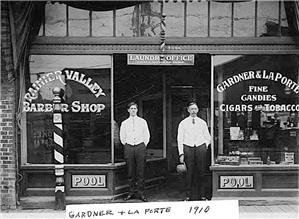

By 1910, according to that year’s census, 3,454 people of Italian heritage were living in Seattle, most in the Rainier Valley. The largest cluster was along Rainier Avenue between Atlantic and McClellan streets but other enclaves developed farther south, especially on Beacon Hill and around Columbia City. The community was served by two Italian language newspapers, Il Tempo, founded in 1908, and Grazzetta Italiana, 1910. (Il Tempo folded in 1913, but the Grazzetta continued to publish until 1961.) There was an Italian Language School, where children of immigrants could learn their parents’ native language; a social hall, operated by the Sons of Italy in America; and a weekly "Italian Radio Hour" on a local station. Neighbors made wine together and played bocce (an ancient Italian bowling game) in backyard courts.

The community lost some of its cohesiveness during World War II. Residents who had been born in Italy were designated "enemy aliens" and subject to curfews and other controls, including restrictions on travel and employment. The social hall shut down; the radio hour went off the air; and the language school was closed. The Italians’ Japanese neighbors, of course, suffered more severe restrictions: they were forced to leave their homes and go to internment camps during the war.

Japanese Community

There was little Japanese immigration to Seattle until the 1890s, when railroads, fish canneries, sawmills, and other labor-intensive industries began recruiting workers to fill a void created by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which had cut off immigration from China. By the turn of the century, Japanese constituted the largest and the fastest growing non-white community in Seattle.

Most of the early immigrants were male and lived in apartments and hotels in "Japantown" (now the International District). In 1907 the U.S. and Japan came to a "Gentlemen’s Agreement" which curtailed the number of single men who were allowed to enter the U.S. but did not restrict immigration by women. One consequence was an increase in the number of young Japanese women who came to Seattle as "picture brides" (to marry men who had selected their photos from catalogs supplied by a broker). The Japanese population remained centered in the International District but an increasing number of young families established homes, farms, and businesses to the south.

Washington’s 1889 Constitution had banned the sale of land to "aliens ineligible in citizenship" (only Asians were not able to become citizens). The Alien Land Law of 1921 specifically made it illegal for Asians to rent, lease, or buy land. Japanese entrepreneurs got around the law by making arrangements with supportive Caucasians, who obtained land for them and technically employed the Japanese as "managers." For example, when Fujitaro Kubota (1879-1973) bought five acres of logged-off swampland near Rainier Beach in 1927 and began turning it into a commercial nursery, he did so in the name of a white friend.

Like their Italian counterparts, Japanese immigrants made efforts to pass their language and traditions on to their American-born offspring. The Japanese Language School (Nihongo Gakko), founded in 1902, provided instruction not only in language but also in the history and culture of Japan. The school began sponsoring annual picnics in Jefferson Park on Beacon Hill in 1919 to showcase folk dances and traditional music. The last picnic was held in May 1941, seven months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent forced removal and incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans on the West Coast.

Many of the internees never returned to Seattle, but Kubota was among those who did. After the war, he and his family restored and continued expanding and developing the Kubota Garden, now a 20-acre Seattle public park.

Shifting Demographics

The demographics of Southeast Seattle began to shift during World War II. The city’s overall Japanese population dropped, from about 7,000 in 1940 to 5,800 in 1950, but the percentage living in the southeast district, particularly on Beacon Hill, increased. Thousands of African Americans moved to Seattle for defense jobs, boosting the black population from 3,800 in 1940 to 15,700 10 years later. Discriminatory housing practices confined most blacks to the Central Area but some found homes in the Rainier Valley, particularly in a government housing project at Holly Park. Meanwhile, Jewish families began to move from the Central Area into the Seward Park neighborhood. Formerly white neighborhoods in Southeast Seattle gradually became more multiethnic, while the Central Area -- once multiethnic -- became predominantly African American.

What writer John Hoole calls "the decisive period in Southeast Seattle’s demographic history" came during the 1960s -- coincidentally the period when the Postal Service implemented the Zone Improvement Plan (replacing two-digit postal zones with five-digit ZIP Codes). A postwar building boom in the Rainier Valley, a decrease in the supply of affordable housing in the Central Area, and the adoption of an open housing ordinance in 1968 all contributed to a dramatic increase in the number of minorities living in Southeast Seattle. By 1970 African Americans accounted for 14 percent of the district’s population; Asians, 17 percent.

The newcomers included several hundred Samoans. Although the U.S. had had possession of six of the 15 Samoan Islands (in the South Pacific) since 1900, there is no record of any Samoans migrating to the Northwest until 1951, when the U.S. Navy closed its base at Pago Pago and relocated Samoan servicemen and administrators and their families to Tacoma’s Fort Lewis. When their tours of duty ended, many of these people moved to Seattle. By the early 1950s, 15 extended Samoan families were living in Southeast Seattle, primarily in Brighton and Columbia City. The community continued to grow as new arrivals from American Samoa joined established family members.

Hoole points out that the increasing diversity in Southeast Seattle was not just the result of new residents moving in, but of others moving out. Between 1960 and 1970, the white population decreased by 20 percent. It continued declining until 2000, when fewer than one-fourth of the people living in the census tracts that make up Southeast Seattle were non-Hispanic whites.

Influx of Filipinos

The passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 and the end of the Vietnam War 10 years later led to dramatic changes in the composition of the Asian community in Southeast Seattle. The law repealed earlier measures that had favored immigration from northern Europe and severely restricted that from Asia and Africa. One immediate effect was an increase in the number of immigrants coming to Seattle from the Philippine Islands. Filipinos soon surpassed Japanese and Chinese as the largest group of Asian Americans in Seattle. After 2000, however, they were surpassed in turn by Vietnamese and other Southeast Asians, who now constitute almost half of the Asian population in the 98118 ZCTA.

The first Filipinos to settle in Seattle were workers who had been hired to lay cable in the Pacific in 1906. Because the Philippines was a territory of the U.S. (acquired from Spain in 1899), Filipinos were classified as "nationals" rather than "aliens," giving them a favored immigration status at a time when other Asians were subject to increasing restrictions. They were allowed to enter the U.S. freely, without passports, and were unaffected by the passage of the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924, which virtually ended immigration from China and Japan.

Filipinos were the fastest growing Asian population in Washington state in the 1920s. Like other minority groups, they often encountered discrimination and resentment. Many were relegated to work as "houseboys" in hotels and residences, as fieldhands on farms, and as "Alaskeros" (cannery workers), doing menial labor. Anti-Filipino sentiment in Congress resulted in the passage of a 1934 law that reclassified Filipinos as "aliens" and limited the number who could be admitted to 50 per year. The Filipino Repatriation Act of 1935 pressured Filipinos to leave the U.S. by offering them free passage back to the Philippines. By the time the act was declared unconstitutional, in 1940, the Filipino population statewide had dropped to 2,222, from 3,480 10 years earlier.

The immigration reforms of 1965 allowed for the entry of up to 20,000 Filipinos to the U.S. annually, compared to the quota of 50 imposed in 1934. The 1960 census counted only about 7,000 Filipinos in the entire state of Washington. By the end of the 1990s, there were an estimated 30,000 in Seattle alone, including about 7,500 in the neighborhoods of Southeast Seattle. Indeed, a part of Lake Washington’s Seward Park became known as "Pinoy Hill" (after an informal name for Filipinos) because of the number of family gatherings, church picnics, and community celebrations held there. Filipinos accounted for 28 percent of the Asian population in the 98118 ZCTA in 2010 (down slightly from 30 percent in 2000). Only 4 percent of that population was Japanese, historically the predominant group among Asians in Seattle.

Southeast Asians

Immigrants from Southeast Asia came to the Seattle area in three waves. The first, arriving after North Vietnamese communists took control of Saigon (the capital of South Vietnam) in 1975, included many South Vietnamese military officers, government employees, and professionals who had supported the Americans during the war. For the most part, they were urbane, well educated, and adapted easily to life in the U.S.

The second, much larger wave included the "boat people" -- so named because many had escaped from Vietnam on small boats, often under harrowing circumstances, making their way to refugee camps in Thailand and from there to the U.S. They entered the country under the sponsorship of American families, often associated with churches. Refugees from Cambodia and Laos also became part of this second wave. The first groups arrived in Seattle in 1978. Most had been farmers in small villages; they had little or no formal education or knowledge of Western culture, and they faced more challenges in adapting to life in urban Seattle than their predecessors.

The third wave included those who came via the Orderly Departure Program, launched by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in 1979 and operated until 1994. More than half a million Vietnamese were resettled in the U.S. through this program, which focused on family reunification. Others gained entry through the 1987 Amerasian Homecoming Act, which applied to the children of Vietnamese mothers and American servicemen who had been abandoned by their fathers; and through a 1989 agreement that permitted former political prisoners and their families to come to America.

The influx of Southeast Asians added new layers to multiculturalism in Southeast Seattle. Families pooled their resources to open grocery stores, markets, nail salons, restaurants, and other businesses. Many of these enterprises sprang up along what would become Little Saigon, on South Jackson Street, as well as in Southeast Seattle, along Rainier Avenue and Martin Luther King Jr. Way. The immigrants themselves were culturally diverse. The Laotians, for example, came from three distinct ethnic groups: the Lao people, from the lowlands; the Hmong and Mien, from the lush mountainous regions; and the Khmu, from northern Laos. They became part of a melange that included Indonesians, Malaysians, and Bengalis -- people of different cultures, religions, and languages, all facing the challenges of adapting to life in a new world.

Recent Arrivals

In recent decades new waves of refugees have found their way to Southeast Seattle. The largest groups have come from the East African nations of Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia -- the "Horn of Africa."

A few Ethiopians came to Seattle as university students in the late 1960s and the early 1970s. Most intended to complete their education and then return to work and live in their homeland. But in 1974, a communist military junta called the Derg (sometimes spelled Dergue) overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie (1892-1975), ushering in a period of political chaos, violence, and famine. About 2.5 million Ethiopians left the country between 1974 and 2009. Thousands ended up in Seattle.

The tangled political history of that part of the world includes a war between Ethiopia and Eritrea that was initiated in 1962, when Selassie annexed the smaller but strategically placed coastal country. Hundreds of thousands of Eritreans fled to refugee camps in Sudan and other African nations, seeking escape from war and drought. A few came to Seattle as students in the late 1960s and early 1970s. A few others jumped ship when their employers’ boats docked in Seattle shipyards. But it was not until the 1980s that significant numbers of Eritrean refugees arrived in Seattle.

The Somali community in Seattle also began as a small group of college students and engineers in the 1970s. It has grown exponentially since 1991, when a coalition of clans ousted the nation's long-standing military government and set off a civil war. The upheaval led to the exodus of thousands of refugees to neighboring Ethiopia and Kenya. These camps remain in place today as successive waves of refugees flee the violence and chaos that have resulted from the absence of an effective central government in Somalia.

East African Community Services, an advocacy group established in Seattle in 2000, estimates that nearly 30,000 East Africans are now living in King County. The exact number is not known. The Census Bureau does not identify people of African heritage by their nationality, and immigration statistics don’t track immigrants who are admitted to one state but then move elsewhere. Still, it’s revealing that Somali students are the second largest bilingual group in the Seattle Public Schools (after Hispanics).

Mini-United Nations

In 98118 the demographic churn over the last half century has created what sometimes feels like a mini-United Nations. According to Miguel Castro, data analyst for the Seattle public school district, 56 percent of the students enrolled in schools in that ZIP code come from homes where a language other than English is spoken -- compared to only 23 percent of students district-wide. Chinese, Somali, Spanish, and Vietnamese are the most common languages, but 56 others are spoken, ranging from Amharic (Ethiopian) to Tagalog (Filipino).

Among the religious institutions with 98118 addresses are three Orthodox synagogues, two Catholic churches, two Buddhist temples, and a mosque. The Baptists have three churches, while Ethiopians, Samoans, and Latinos have two each. The website www.represent98118.org sums it up this way: "Within a few blocks of one another, worshipers may be engaged in an African American Bible fellowship, an evangelical Ethiopian students union, a Filipino-American Catholic Mass, a Haida sacred dance circle, a Mexican Pentecostal revival, an Orthodox Jewish Sabbath observance, a Society of Friends meeting, a Samoan gospel choir, a Somali Muslim prayer service, or a Vietnamese Buddhist evening chant."

The diversity also extends to economics. Lakefront mansions, Craftsman-style bungalows, and dilapidated apartment complexes sit within blocks of each other. Prices for single-family homes listed for sale in the 98118 ZIP code in August 2012 ranged from $3.5 million for a five-bedroom house with 100 feet of Lake Washington waterfront in the Seward Park neighborhood to $115,000 for a one-bedroom house in Rainier Beach.

"Southeast Seattle is a multi-layered place, full of contrasts and incongruities -- but also unexpected connections and hidden continuities," writes historian Mikala Woodward. She captures the scene with this paragraph:"A second-generation Italian restaurateur rents an old mill’s company store from a group of Filipino developers and turns it into a pizzeria. Chinese and Japanese families that have lived on Beacon Hill for generations shop at Viet Wah Super Foods, alongside Samoan matriarchs and the children of Vietnamese refugees. At the Columbia City Farmers Market, East African women in headscarves and white hipster dads with babies in slings buy vegetables from smiling Hmong ladies, with a mural honoring four African American victims of gang violence in the background."

Coming Together, Moving Apart

Living in proximity with people of other ethnic and racial backgrounds does not necessarily mean living in harmony. Political scientist Robert Putnam, author of Bowling Alone, has found that the more diverse the neighborhood, the greater the tendency for people to "hunker down, to pull in" and clump together along racial, political, social, and spiritual lines ("Talk of the Nation"). What writer Claire Thompson calls "crunchy ideals of diversity" don’t always play out in the real world. At its most extreme, this has manifested itself in violent interethnic conflict among gang members in Southeast Seattle.

John Hoole has suggested that increased diversity can weaken support for the common good. "Where do the interests of Vietnamese refugees, middle-class white homeowners, the well-to-do by the water, new-to-the-neighborhood renters, and African American families who have been in the Valley for generations converge?" he wondered, in a column for the Rainier Valley Post. "There always lurks the depressing possibility that they don’t, that compared with all the other things that make us who we are and bind us to others, geography is circumstantial."

Geography is also stable, whereas demography is not. In recent years, more whites have been moving into 98118 while more people of color have been moving farther south, sometimes out of Seattle altogether. For example, the Samoan population in the 98118 ZCTA dropped from 450 to 240 between 2000 and 2010, with many Samoans decamping for White Center. SeaTac and Tukwila have attracted large numbers of Hispanics (now 20 percent of the population in SeaTac, 18 percent in Tukwila), as well as Somalis, Sudanese, and other African immigrants. The non-white population as a whole in South King County has increased by 66 percent in the past decade. In contrast, the percentage of non-white residents in 98118 has decreased slightly and that of whites has gone up by nearly 15 percent.

The change has been driven in part by rising property values in 98118. Since 1990, the city has replaced the area's two public housing projects (originally built to house defense workers during World War II) with mixed-income developments and built a light rail line along Martin Luther King Jr. Way. Some families couldn’t afford the consequently higher rents or property taxes and joined newly arrived immigrants in relocating to less expensive areas. As a result, "celebrations of the neighborhood’s renewal walk hand-in-hand with fears that it will lose its unique character if lower-income residents are pushed out" (Thompson).

But for the moment, at least, 98118 remains a model of what the Census Bureau says America will look like by 2042: a nation in which "minorities" are the majority.