Washington became one of the first two states, along with Colorado, to legalize adult recreational use of marijuana when voters approved Initiative 502 on November 6, 2012. The vote was the culmination of a long campaign to end legal penalties for possession and use of the plant and its byproducts, a campaign that since the 1970s had won reduced criminal penalties, permitted medical use, and finally legalization (under state law -- marijuana remained illegal, in Washington and elsewhere, under federal law). This essay traces the history of marijuana, a substance that had been used by humans for thousands of years until being demonized and outlawed across much of the world during the twentieth century, and of the movement to end the criminalization of marijuana use in Washington.

Nature's Pharmacy

Nature produces a wide range of medicinal and psychoactive compounds, and humans have used many of them for thousands of years, for healing, for religious purposes, and for recreation. During the millennia when only magic could explain most natural phenomena, plant-derived drugs such as opium and cannabis were believed in many cultures to enhance insight into the mysteries of existence. In some societies their use was sacred, confined to healers and holies who would then interpret the experience for the faithful. In other societies, psychoactive drugs were used by ordinary citizens, to heal, to approach the divine, or for simple enjoyment. It is an indisputable fact that throughout recorded history a not-insignificant percentage of the human race has used chemical compounds to alter, at least temporarily, how they experience reality. With the exceptions of alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine, marijuana is probably the most widely used psychoactive substance known to humans, and the only one of the four that has been illegal in America since the repeal of alcohol prohibition in 1933.

Unlike most plants and fungi that contain psychoactive chemicals, the hemp plant (the dried leaves and flowers of which are marijuana) has many practical uses. Since as long ago as 8000 B.C.E. hemp has been manufactured into ropes, clothing, mats, and a variety of other useful articles. The first unambiguous written mention of hemp being used for medicinal purposes appears in the Rh-Ya, a fifteenth century B.C.E. Chinese pharmacopeia. The Atharva Veda, a compilation of Hindu hymns and scripture that first was reduced to writing ca. 700 B.C.E., speaks of hemp as a sacred plant because "a guardian angel (Deva) lives in its leaves" ("Marijuana Medicine: A World Tour ... "). Favorable mentions of hemp under a variety of names (but never "marijuana"), appear in the early records of many societies, particularly in Asia and South Asia.

Material and Medicine

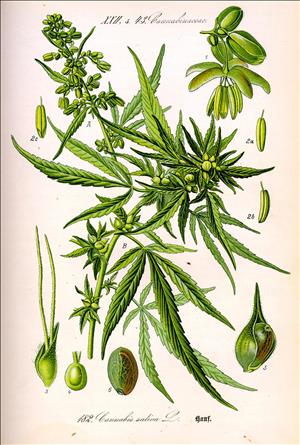

The botanical family Cannabaceae has one genus, Cannabis L. (the "L" denotes the Linnaean taxonomy), the common and versatile hemp plant. Following the Linnaean ladder, the Cannabis L. genus has but one species, Cannabis sativa L., which gives rise to three subspecies, C. Sativa, C. Indica, and C. Ruderalis (the latter, until recently, found only in Russia and other northern latitudes). A fourth name, C. Americanus, appears to be an exercise in geographical hubris, with no scientific basis or separate existence in nature. Etymologists believe that the words "hemp" and "cannabis" are derived from a single Indo-European root that first entered the western world as the Greek kannabis, probably borrowed from the Scythian civilization from the steppes of Central Asia, where hemp itself may have first been used by humans.

Hemp probably originated in Central Asia and spread with human migration and trade. Shreds of hempen cloth and other hemp products have been found in archaeological sites in Asia, Africa, and Europe. Certainly by the thirteenth century C.E., and probably much earlier, hemp was used as a material throughout most of Europe. It is likely that in most places where hemp was used as a material, it was also used for its physical and psychoactive effects. In the fifth century B.C.E. the Greek historian Herodotus told of Scythians who

"cultivated a plant that was much like flax but grew thicker and taller; this hemp they deposited upon red-hot stones in a closed room –– producing a vapor ... 'that no Grecian vapor-bath can surpass. The Scythians, transported with the vapor, shout aloud'" ("Marijuana In the Old World").

The qualities that made hemp commercially valuable were strength and durability. Hemp ropes were sturdy, long-lasting, and resistant to stretching, and were used on sailing ships for centuries, notably the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria on which Columbus sailed in 1492. Fabric made from hemp for clothing is porous, yet traps air, making it useful in both hot and cool climates. Hemp is also economical -- studies have shown that a plot of cultivated hemp can produce 250 percent more usable fiber than cotton and 600 percent more than flax grown in the same space.

In the mid-sixteenth century the Spanish introduced the plant into the Americas in what is today Chile, and it spread north from there. In colonial days, the growing of hemp for manufacturing use was widely encouraged, and was mandated by law in the colony of Virginia in 1619. Hemp horticulture remained common in the United States until after the Civil War. Up through the early 1900s, extracts made from the leaves and flowers of the hemp plant were found in many patent medicines.

In an interesting sidelight, hemp production was encouraged again by the United States government during World War II, at a time when the possession or use of marijuana was illegal in every state. But the other product of the plant, hemp fiber, was deemed critical to the war effort, and farmers were granted licenses to supply the military with its needs. This brief love affair ended with the war, and hemp once again became a forbidden crop.

Nomenclature

The origin of the word "marijuana" and its cognates, "marihuana" and "marajuana," is obscure, although of relatively recent vintage. The first written mention appears to be an 1894 Scribner's Magazine article, "The American Congo," in which author John Bourke referred to "mariguan," a plant that grew in profusion along the Rio Grande border between Mexico and the United States ("The Mysterious Origins of the Word 'Marihuana'"). Variations soon appeared in other publications, including marihuma (Punch, 1905); mariahuana (Pacific Drug Review, 1905); marijuana (The American Practitioner, 1912); and marihuana (The Los Angeles Times, 1914). Today (2012) the most common term is "marijuana," although the alternate spelling "marihuana" still appears on occasion, often in laws and regulations.

The origins of many of the modern names used to describe the leaves and flowers of the hemp plant are equally obscure. In the Western Hemisphere alone, a sampling would include pot, grass, weed, bud, jay, reefer, joint, ganja, herb, dope, smoke, mary jane, skunk, herbage, doobage, and many others.

Marijuana, the Brain, and the Body

In 1990, Miles Herkenham, Ph.D., a senior researcher at the National Institutes of Health, discovered receptors on the surface of human brain cells that were specific for cannabinoids (the psychoactive components of marijuana), proving that humans are born with the capacity to use the chemicals in some way. Later studies found that the primary cannabinoid receptor, called CB1, exists in far higher concentrations in the brain than any other type of receptor. A second cannabinoid receptor, called CB2, later was found on cells of the immune system, intestinal tract, liver, spleen, kidney, bones, heart, and peripheral nervous system. These findings led to the obvious question: Why are humans born with such specific and numerous receptors for cannabinoids?

The study of how marijuana works in the human brain is one of those areas that becomes more complicated the more deeply one looks. For many years it was thought that the only psychoactive ingredient in marijuana was tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but later studies established that marijuana has at least 60 different cannabinoids, and unraveling their function and effects will take years of additional research.

It is known that THC molecules come in two mirror-image configurations, labeled left-handed (-) and right-handed (+). For reasons that no one is close to answering, the psychoactive effects of "left-handed" THC are 10 to 15 times more potent than those of the right-handed variety. It has also been established that marijuana's psychoactive effects do not result from changes to the brain's dopamine "reward" system, as is the case with heroin, morphine, cocaine, methamphetamine, and other highly addictive drugs.

Perhaps the most interesting finding came in 1992 with the discovery that the human body produces its own cannabinoids. Studying these "endocannabinoids" and the pathways through which they work, scientists came to the following conclusion:

"These discoveries of the cannabinoid receptors, endocannabinoids and the related enzymes make up what is now called the endocannabinoid system and it seems to be essential in most if not all physiological systems. The endocannabinoid system is essential to life and it relates messages that affect how we relax, eat, sleep, forget and protect" ("The Endocannabinoid System")

Any substance that alters consciousness always draws suspicion and criticism. Pot has been no exception, and for a good part of the twentieth century it was demonized in America by government and press alike, often referred to with such hysterical epithets as "the weed with its roots in Hell." Pulp magazines, salacious paperbacks, and low-budget movies all took up the cause, telling lurid tales of promising young men and women transformed into murdering maniacs after just one puff of marijuana. It was a credulous time, marijuana had few or no defenders, and the lies and gross exaggerations soon became accepted as true by most Americans.

Prohibition

In 1914, with strong support from Progressive forces, the United States passed its first federal anti-narcotics law, the Harrison Tax Act. It sought to regulate by taxation opium, morphine and its various derivatives, and the derivatives of the coca leaf, primarily cocaine. Before the act's passage, people addicted to these chemicals could obtain maintenance levels of the drugs from physicians. After the Harrison Act, such prescribing was deemed to fall outside of acceptable medical practice. Addicts did not disappear, of course; the drug trade was simply driven underground and into criminal hands. Barely more than a year after passage of the new law, a well-regarded medical journal described its unintended ill effects:

"Abuses in the sale of narcotic drugs are increasing ... . A particular sinister sequence ... is the character of the places to which [addicts] are forced to go to get their drugs and the type of people with whom they are obliged to mix. The most depraved criminals are often the dispensers of these habit-forming drugs. The moral dangers, as well as the effect on the self-respect of the addict, call for no comment" ("Editorial Comment").

The nation's first experiment in full prohibition of a psychoactive substance came with the 1919 ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment, which made illegal "the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors" ("Eighteenth Amendment -- Prohibition of Intoxicating Liquors"). Neither the Eighteenth Amendment nor the laws that implemented it (primarily the Volstead Act) made the consumption of alcohol illegal, and for most of our nation's history that was true for narcotics as well. It was widely held to be beyond the power of the federal government to outlaw the mere use of alcohol and drugs; if it was to be done at all (and many thought it should not), it would be left to the criminal statutes of the individual states.

The unintended consequences of the Harrison Tax Act, the Eighteenth Amendment, and the Volstead Act did not improve with age. In 1926, 12 years after its passage, the Harrison Act (and 18th-Amendment Prohibition) brought this comment from another respected medical journal:

"The Harrison Narcotic law should never have been placed upon the Statute books of the United States ... .

"The doctor who needs narcotics used in reason to cure and allay human misery finds himself in a pit of trouble. The lawbreaker is in clover ... . It is costing the United States more to support bootleggers of both narcotics and alcoholics than there is good coming from the farcical laws now on the statute books.

"As to the Harrison Narcotic law, it is as with prohibition [of alcohol] legislation. People are beginning to ask, 'Who did that, anyway?'" ("The Harrison Narcotic Act").

The Evolution of America's Drug Laws

Marijuana first came to the United States in appreciable quantities with Mexican immigrants who came here in large numbers after the start of the Mexican Revolution of 1910, and the anti-marijuana movement was from the start tainted by racism and nativism, much like the earlier anti-opium laws that targeted Chinese immigrants. The racial bias became only stronger when the use of marijuana spread among black jazz musicians and into the nation's inner cities. By 1931 all but two states west of the Mississippi River, and several in the East, had made possession or use of marijuana a crime, even though many of them had seen little or none of either.

In 1932 Congress passed the Uniform Narcotic Drugs Act, designed to provide the states with model uniform legislation for regulating and criminalizing drugs. Under the act, marijuana was classified as a dangerous narcotic, a scientific fiction that made it the legal equivalent of opium, heroin, and morphine. By 1936 all 48 states then in the union had laws criminalizing marijuana, many modeled after the uniform act.

In Washington, marijuana had been classified as a narcotic since 1923, and the state did not adopt the Uniform Narcotics Drug Act until 1951. When it finally did, it was simply old wine in a new bottle -- cannabis was still deemed a narcotic, a mischaracterization that would be used to justify the arrest, prosecution, and often-long imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of American citizens during the twentieth century.

Despite the fact that it was illegal in every state by 1936, Congress remained unsatisfied that the threat posed by marijuana had been adequately addressed. The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 imposed a tax on marijuana growers, distributors, sellers, and buyers (the Harrison Tax Act of 1914 had not covered marijuana). At the Congressional hearings on the bill, Dr. William C. Woodward, chief counsel to the American Medical Association, testified against the legislation, stating that the association knew of "no evidence" to support the conclusion that marijuana was a dangerous drug ("Statement Of Dr. William C. Woodward"). Legislators were unimpressed, and the tax act passed easily.

Requiring producers, sellers, and users of marijuana, an illegal substance, to register and pay a federal tax appeared on its face to run afoul of the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. Indeed it did, but so successful was the demonization of marijuana that it took 32 years, until 1969, for the U.S. Supreme Court to rule, unanimously, that the Marijuana Tax Act "was clearly aimed at bringing to light violations of the marihuana laws" and thus incompatible with the Fifth Amendment (Leary v. United States).

Demonizing Marijuana

Harry J. Anslinger (1892-1975) was the first head of the Bureau of Narcotics, created by Congress in 1930 as a division of the Treasury Department. He would serve in that post for the next 32 years, much of which time he spent railing against marijuana. Anslinger had been an assistant commissioner in the bureaucracy of alcohol Prohibition and was an opponent of any drug use outside of carefully regulated medical treatment. Anslinger believed marijuana to be one of the greatest dangers ever to face Western civilization, and he made no bones about it:

"How many murders, suicides, robberies, criminal assaults, holdups, burglaries, and deeds of maniacal insanity it causes each year, especially among the young, can be only conjectured ... . No one knows, when he places a marijuana cigarette to his lips, whether he will become a philosopher, a joyous reveler in a musical heaven, a mad insensate, a calm philosopher, or a murderer" ("Marijuana Assassin of Youth," The American Issue, July, 1937)

"I believe in some cases one cigarette might develop a homicidal mania, probably to kill his brother ... . Probably some people could smoke five before it would take effect, but all the experts agree that the continued use leads to insanity" (Marijuana Tax Act Congressional Hearing, July 12, 1937)

"If the hideous monster Frankenstein came face to face with the monster marihuana, he would drop dead of fright" (from a 1937 speech to the Women’s National Exposition of Arts and Industries, in New York City).

Anslinger kept up his tirades throughout his long career and beyond. His views were widely publicized, and they influenced public perception of marijuana for decades. He died in 1975, still berating marijuana to anyone who would listen, with a passion that by then seemed merely strange.

The Controlled Substances Act of 1970

For nearly the first two centuries of its existence, the federal government was content to leave the criminalization of drugs up to the various states, aided by model laws like the Uniform Narcotic Drugs Act of 1932. This started to change with the 1965 passage of the Drug Abuse Control Amendments to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act of 1938. Although silent on the issue of marijuana, this law marked the first time that the possession and use of narcotic drugs were criminalized under federal law, and it augured more to come.

Just five years later, in 1970, the whole drug enforcement landscape was altered with passage of the federal Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act. Section II of that law, entitled the Controlled Substances Act, greatly expanded the federal reach, which now extended fully into the criminal enforcement of drug laws. All drugs covered by the act were now under federal criminal jurisdiction. Included were hard narcotics and any other drugs that were deemed "dangerous," such as marijuana, mescaline, LSD, and other psychedelics.

The law established "Schedules" in which were categorized nearly every known psychoactive and narcotic drug. Schedule I listed those considered most dangerous, defined as having a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use, even under medical supervision. Marijuana was included in Schedule I, along with such things as heroin. Alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine (all major industries in America) were expressly excluded from the statute's reach.

Although the law passed handily, Congress evidenced some ambivalence about marijuana, calling for a commission to examine the question in depth and issue a report by 1972. President Richard M. Nixon (1913-1994) appointed the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse, headed by former Pennsylvania governor Raymond P. Shafer (1917-2006), a moderate Republican. Pursuant to its mandate, the commission conducted a thorough review of all the medical, social, and legal issues surrounding marijuana and in March 1972 issued its report. The core conclusion of the Shafer Commission faced down 40 years of propaganda-driven hysteria:

"Neither the marihuana user nor the drug itself can be said to constitute a danger to public safety. Therefore, the Commission recommends ... [the] possession of marijuana for personal use no longer be an offense, [and that the] casual distribution of small amounts of marihuana for no remuneration, or insignificant remuneration no longer be an offense" ("Nixon Commission Report").

Nixon tried to intervene to change the commission's findings before the report was issued, saying to Shafer, in a conversation recorded in May 1971:

"You're enough of a pro to know that for you to come out with something that would run counter to what Congress feels ... and what we're planning to do would make your commission just look bad as hell" ("Nixon Commission Report").

One month later, in June 1971, before receiving the formal Shafer recommendations, Nixon publicly declared a "War on Drugs," which he called America's "public enemy No. 1" ("Timeline: America's War on Drugs"). Shafer did not buckle, but his commission's report was simply ignored, by federal and state officials alike, then, and for several decades to follow.

The federal Drug Enforcement Agency was established in 1973 to enforce the new drug laws, often working hand-in-hand with state authorities. Over the next 30 years, more than 13.2 million Americans would be arrested on marijuana charges alone. Most of those arrested were convicted; many of those convicted went to prison.

Checks and Balances

The war on drugs raged for decades, costing vast amounts of money, filling prisons to overflowing (with highly disproportionate numbers of racial minorities), and damaging the lives of many who did nothing more than possess a small amount of a botanical substance that had been known and used by humans for thousands of years. At the same time, millions of young people who had smoked marijuana, and perhaps still did, managed to escape detection, finished their studies, started careers and families, and appeared to have suffered few if any permanent ill effects. For many that experience seemed to put the lie to the warnings of the drug warriors; cognitive dissonance set in, and not just among the young. Authority was increasingly questioned; Watergate and the war in Vietnam had disabused much of the American public of the belief that government could always be trusted to tell the truth.

Once time and experience tempered the hyperbole about marijuana, the issue could be seen as quite simple -- did the use of marijuana have negative personal or societal consequences of a magnitude that warranted criminal punishment? A growing number of Americans came to believe that the answer to that query was "no."

Nowhere did this happen more fully or more emphatically than in Washington. Which is not to say that change was rapid; to the contrary, it was a slow, incremental, and cautious process by state and local governments, acting at times on their own, at other times pushed along by the will of the people expressed through the ballot box.

The Washington Experience

As mentioned, Washington was early to criminalize the "habitual" use of marijuana, whatever that meant (Massachusetts was first, in 1911, followed by Utah in 1915). The state's Narcotics Act of 1923 also declared:

"The term narcotic drugs wherever used in this act shall be deemed and construed to mean and include opium, morphine, cocaine, alkaloid cocaine, cocoa [sic] leaves, or alpha or beta eucaine, heroin, codeine, dionin, cannabis americana, cannabis indica and other salts, derivatives, mixtures or preparations of any of them" (1923 Wash. Laws, ch. 47).

Thus even before the federal government made the same error, Washington embedded in its law the mistaken notion that marijuana was a "narcotic drug," the chemical equivalent of opium and morphine. Yet marijuana prosecutions remained very rare for many years, simply because for decades its use in Washington was almost unknown. Only one case involving marijuana reached the State Supreme Court between 1923 and 1939, and it mentioned the drug laws only in passing. The state had the law, but not the lawbreakers. What was going on?

A 1970 study from the Virginia Law Review attempted to explain why states with no recognized marijuana "problem" would nonetheless pass laws imposing serious penalties for its possession or use. The study concluded:

"Concern about marijuana was related primarily to the fear that marijuana use would spread, even among whites, as a substitute for the opiates and alcohol made more difficult to obtain by federal legislation. Especially in the western states, this concern was identifiable with the growth of the Mexican-American minority. It is clear that no state undertook any empirical or scientific study of the effects of the drug. Instead they relied on lurid and often unfounded accounts of marijuana's dangers as presented in what little newspaper coverage the drug received. It was simply assumed that cannabis was addictive and would have engendered the same evil effects as opium and cocaine. Apparently, legislators in these states found it easy and uncontroversial to prohibit use of a drug they had never seen or used and which was associated with ethnic minorities and the lower class" ("The Forbidden Fruit and the Tree of Knowledge ... ").

Marijuana arrests remained rare in Washington for several more decades. Then the 1960s happened. Marijuana use became commonplace among young people, particularly college students. As happened with alcohol prohibition, the laws against marijuana, rather than controlling the perceived problem, created a generation of casual lawbreakers. But as late as 1967, The Seattle Times ran a column by Dr. Max Rafferty, California's superintendant of public instruction, in which he said:

"Marijuana is dope. Cannabis sativa. Hashish. Western style. It distorts and twists and perverts. Its users graduate to heroin and morphine. Its pushers deserve the strictest penalty the law allows" ("Purported Good in Dope 'Cult' Termed Nonsense").

Such comments had little basis in science or experience. The idea of marijuana as a "gateway" drug that led inexorably to heroin and morphine addiction seemed to many an exercise in faulty logic. Certainly some who used marijuana went on to use harder drugs. Just as certainly, these were substantially outnumbered by those who didn't.

As more and more people experimented with marijuana and survived seemingly unscathed, many scientists, educators, and politicians began questioning the severity, even the very existence, of the laws against marijuana. A small step came in 1971, when the Washington State Legislature finally recognized that marijuana was neither an opiate nor a narcotic. Marijuana (spelled "marihuana" in the statute) and its derivatives were now given a category of their own, and possession of less than 40 grams would be charged as a misdemeanor. But even this new category remained under the umbrella of Schedule I -- drugs deemed to have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use.

Additional changes to the law were incremental and slow in coming, but always moved in the direction of lenity, steadily easing the penalties for the possession and use of small amounts of marijuana. In one small example, in 1975 the licensing law for massage therapists in Washington was changed to make convictions involving any schedule I controlled substance "except marijuana" grounds to withhold a license (1975 Wash. Laws, ch. 280). Although rather backhanded, this was another legislative recognition that marijuana should be treated differently from other Schedule I drugs. Over the ensuing decades, other small changes were made that, while leaving marijuana classified as a Schedule 1 drug, mandated that it be treated differently, and more leniently, than those it was grouped with.

Medical Marijuana

By the 1990s a growing segment of the public in Washington was looking at a more fundamental issue, which the legislature's reforms, although tending towards increased leniency, didn’t address: Was marijuana even dangerous enough to warrant the scrutiny of the criminal law? With a few notable exceptions, legislators seemed unwilling to tackle that central question, preferring instead to avoid taking a public stand while quietly softening the anti-marijuana laws with piecemeal amendments and exceptions.

Perhaps this was wise at the time: All frontal attacks on anti-marijuana legislation, both state and federal, had come to naught. Yet millions who had smoked pot in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s were now mature adults, working in all trades and professions, raising families, engaging in politics. Both Bill Clinton (b. 1946) and Newt Gingrich (b. 1943) admitted to having smoked pot, though Clinton famously found it necessary to deny having inhaled. Fewer and fewer Americans viewed the use of marijuana by adults as harmful, much less criminal.

In many states, including Washington, law enforcement was no longer aggressively pursuing casual users of marijuana; most busts came when the police, in the course of investigating more serious crimes, stumbled upon marijuana and felt duty-bound to enforce the law. And, as always, there was a distinction made between users and sellers, with the latter receiving far greater police attention and more severe punishment.

The full-on attack against Washington's marijuana laws started when Joanna McKee of Bainbridge Island was arrested in May 1995 and charged with providing marijuana to a network of people suffering from AIDS, multiple sclerosis, and cancer. McKee and partner Ronald Miller ran the "Green Cross Patient Co-op," and this was the first time in the nation that law enforcement had gone after the increasingly common medical-marijuana "buyers' clubs" ("Selling Just What Doctor Can't Order ... "). McKee avoided trial when a judge ruled that the search warrant used to seize the evidence (162 marijuana plants, which were not returned) was invalid, and she remained active in the fight to legalize medical-marijuana.

McKee's case brought to the public's attention Ralph Seeley (1948-1998), a Tacoma attorney and terminal cancer patient. Seeley, whose extreme suffering from chemotherapy and multiple surgeries had been alleviated with marijuana, sued the State, contending that the statute classifying marijuana as a Schedule I drug that could not even be prescribed by physicians was unconstitutional. At the time, Seeley made a prediction that would come true in Washington, but not until after his death:

"I think it's an issue like segregation, like women's rights. Ultimately, society will come to its senses and realize this [prohibition] is irrational and destructive, and do away with it" ("Selling Just What Doctor Can't Order ... ").

In October 1995, Pierce County Superior Court Judge Rosanne Buckner agreed with Seeley, ruling that marijuana should be available for doctors to prescribe, something that its Schedule I classification prohibited. The State appealed, and in July 1997 the State Supreme Court ruled against Seeley by an 8-1 margin, holding that under the state constitution only the legislature could enact, modify, or repeal laws regulating the sale of drugs and medicines. The lone dissent was by Justice Richard Sanders who, in an opinion that quickly became famous in legal circles, wrote:

"I wonder how many minutes of Seeley's agony the Legislature and/or the majority of this court would endure before seeing the light. Words are insufficient to convey the needless suffering which the merciless State has imposed" ("Court Says Medical Use of Marijuana Is Illegal ... ").

Seeley died on January 21, 1998, and although he failed in the courts, his efforts sparked a movement to put the question of medical marijuana up for a decision by the voters. The first attempt, Initiative 685, made it to the 1997 ballot. I-685 was criticized as poorly drafted and for its inclusion of drugs other than marijuana, and was soundly defeated. But Seeley's plight also was heard in Olympia, where State Senator Jeanne Kohl-Welles (b. 1942), a Seattle Democrat, submitted a bill in the 1998 legislative session to legalize the medical use of marijuana. It lost as well, but the ball was rolling, and it would not now be easily stopped.

In 1998 a more limited and carefully drafted proposal for medical marijuana, Initiative 692, made it onto the election ballot. Its core provision read:

"Qualifying patients with terminal or debilitating illnesses who, in the judgment of their physicians, would benefit from the medical use of marijuana, shall not be found guilty of a crime under state law for their possession and limited use of marijuana" ("Complete Text of Initiative 692").

The proposal also provided protection for physicians and caregivers and was clearly limited to marijuana. In November 1998 it passed by a greater than two-to-one margin. Similar measures passed in Alaska, Nevada, Oregon, and Arizona, and it appeared that sentiment nationwide on the issue of marijuana was finally changing.

Nevertheless full legalization was a long way off and opposition to any marijuana use remained strong. In 2001 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, despite substantial scientific evidence to the contrary, that marijuana had no recognized "medical benefits" that would protect users from felony drug charges under federal law. Federal law enforcement could still prosecute people using medical marijuana legally under state laws, but most law-enforcement agencies in the state indicated that they would neither make such arrests themselves nor cooperate with federal agents in doing so.

More Liberalization

In Washington, the medical-marijuana law, which at first was terra incognito for patients, medical providers, growers, dispensers, legislators, and law-enforcement personnel alike, evolved slowly over the course of years. Rules had to be established for growing and dispensing the product. Diseases and conditions that could qualify for treatment with marijuana had to be identified. Allowed amounts of the drug had to be determined. As in most states that had authorized the medical use of marijuana, the rules tended to become more liberal as time went on. Federal officials made threats of prosecution now and then, but the editorial pages of many Washington newspapers defended what was widely seen as a successful experiment, one that eased the suffering of many Washingtonians while causing no detectable harm to the public good.

In Seattle, particularly, the public mood appeared to be that more liberalization was needed, and that the place to do it was the voting booth. In a rare example of voters directly setting the working details of law enforcement, city voters in 2003 passed an initiative directing that:

"The Seattle Police Department and City Attorney's Office shall make the investigation, arrest and prosecution of marijuana offenses, where the marijuana was intended for adult personal use, the City's lowest law enforcement priority" ("Seattle Initiative 75").

In Washington, Oregon, and California, medical-marijuana laws were implemented with great liberality, perhaps more than the voters intended, and prescriptions were rather easy to obtain. By 2009, there were an estimated 35,500 Washingtonians with prescriptions to legally purchase marijuana for medical purposes (the figure is an estimate because the state government does not maintain a registry of users). Nationwide, the total number was more than 577,000. In Washington, 5.5 persons out of every 1,000 had a prescription, the same percentage found in Oregon and California, and much higher than the 1.9-per-thousand average among all 13 states then allowing such use. It seemed likely that the push for full legalization would come from among these three Western states, and indeed by 2012 all three saw legalization initiatives on the ballot, although only Washington (along with Colorado) approved such a measure.

Legalization

Proponents tried first in California, bringing Proposition 19, which would have legalized marijuana use and sales, to the ballot there in 2010. Despite arguments that legalization would increase tax revenues, curtail drug violence, and reduce racially disproportionate arrests, Prop 19 was strongly opposed by state and federal law enforcement officials, including White House Drug Policy Director (and former Seattle police chief) Gil Kerlikowske (b. 1949). It lost by a wide margin, failing even in northern California's famed marijuana-growing "Emerald Triangle."

Despite the California results, supporters of full legalization in Washington believed the state's voters were ready to take this last step, and efforts began to put a measure on the statewide ballot for the November 2012 election. Sponsors filed Initiative 502 with the Secretary of State's office on May 10, 2011, and submitted petitions bearing more than 340,000 signatures on December 29 of that year. That was more than enough to place the measure before the state legislature, which had the options of enacting it as written; submitting it to the voters for approval or rejection; or crafting an alternative, in which case both the original proposal and the alternative would have been placed on the ballot at the next state general election. The legislature took no action, leaving it up to the voters to decide.

Early support for Initiative 502 came from some surprising sources, including John McKay, a Republican and former U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Washington; Seattle City Attorney Pete Holmes (both McKay and Holmes were sponsors of the initiative); Charles Mandigo, former special agent in charge of the Seattle office of the F.B.I.; 13 newspaper editorial boards; four retired judges; 21 current or retired members of city and county councils across the state; and at least 77 organizations, ranging from the ACLU to Law Enforcement Against Prohibition. Well-known Seattle travel guru Rick Steves (b. 1955) was an early financial supporter. Many other people from all walks of life came on board to express support as the campaign picked up speed and gained credibility.

There wasn't a lot of organized opposition. The state association of sheriffs and police chiefs and some drug-prevention groups opposed I-502 but did not spend money against the measure. Much of the most vocal criticism came from some medical marijuana supporters, who objected to the initiative's provisions on driving while intoxicated. The "Argument Against" I-502 in the official voters pamphlet was split between legalization opponents and legalization supporters who argued that the measure was not real reform.

The election was not particularly close. Twenty Washington counties opposed the measure while 19, including all the largest in population, approved. In general, the law received strong support in Western Washington and in Chelan, Okanogan, Ferry, Spokane, and Whitman counties east of the Cascades. The final vote tally was 1,724,209 (55.7 percent) in favor and 1,371,235 (44.3 percent) opposed. The island residents of San Juan County cast the highest percentage vote in favor of the measure -- 68.3 percent. In the 2012 election, voters in Colorado also approved a legalization measure, but Oregon voters, like their California counterparts two years earlier, rejected legalization.

The immediate result of I-502 was that as soon as the law took effect on December 6, 2012, state law no longer prohibited adults over 21 from possessing up to one ounce of marijuana. Initiative 502 also imposed responsibilities on pot smokers. Smoking was not allowed in public places, as with the similar ban on public alcohol consumption. In addition, smoking marijuana was banned wherever smoking cigarettes was prohibited. Driving under the influence of marijuana was treated as harshly as driving under the influence of liquor, and the initiative prescribed the level of blood-borne cannabinoids sufficient to establish legal "intoxication."

The rest of the new law was to be implemented over time. The initiative called for state-licensed outlets selling marijuana grown by state-licensed growers in places approved by authorities for such activities. The Washington State Liquor Control Board, which had recently been rendered somewhat idle by the 2011 initiative measure that took state government out of the business of selling packaged hard liquor to consumers, became responsible for formulating policies and procedures to implement the new marijuana law. Until those procedures were implemented, cultivation and distribution (unless permitted under the medical marijuana law) remained illegal.

Taxes on marijuana under the initiative were steep. It called for an initial 25 percent excise tax on virtually every transaction, from grower to wholesaler, wholesaler to retailer, and retailer to customer. The high taxes were intended in part to discourage wider use of marijuana, but were to be periodically evaluated to insure that they were not so high as to encourage a black market that could undercut official prices and sabotage one of the law's major goals.

Washington smokers remained under at least theoretical threat from federal agents (as would state-licensed growers or retailers once that system was established) because marijuana possession and distribution remained a criminal offense under federal law. However, many state, county, and city police departments pledged to not cooperate with federal authorities in investigating an activity that was no longer a crime under state law, and politicians in Washington, as in Colorado, called on federal authorities to respect their states' decisions to legalize marijuana. The U.S. Justice Department apparently listened. On August 29, 2013, Attorney General Eric Holder announced that the federal government would not attempt to preempt state laws legalizing marijuana and, although not reclassifying the drug, would concentrate enforcement efforts on specific targets, including keeping marijuana away from minors, enforcing a ban on cultivating marijuana on public lands, and going after drug trafficking by gangs and cartels. The announcement also warned that the government reserved the right to challenge legalization laws in the future if there were repeated violations in the specific areas of concern.