Lokout was a Yakama Indian, a sharpshooter against the U.S. military, and an intelligence resource for historians. He outlived most of his friends and adversaries. Born of two chieftain families, he was a son of Yakama Chief Owhi (d. 1858) and a grandson of Columbia Chief Sulktalthscosum (d. ca. 1847). As a boy he traveled with his band to hunt bison east of the Rockies, where his grandfather died in battle with the Blackfeet, and to Puget Sound where he stayed with a paternal aunt and a certain cousin who would later become the Nisqually Chief Leschi (1808-1858). As a young man in 1853, Lokout guided Theodore Winthrop (1828-1861) through Washington Territory for a portion of the journey that would form the core of Winthrop’s book The Canoe and the Saddle (1862). As a warrior with his half-brother Qualchan (d. 1858), Lokout helped wage many battles. After Colonel George Wright (1803-1865) hanged Qualchan and set Lokout free in 1858, Lokout married one of Qualchan’s widows. Later that same year, he received a blow from a soldier’s gunstock that left a conspicuous forehead gouge that remained for the rest of his life. Much later, he allegedly fought at the Battle of Little Bighorn. He then settled on the Spokane Reservation and lived out the remaining decades of his long life in relative peace. Lokout went by many names, a practice common in his time, including Loolowcan, Luqaiot, Laquoit, Quo-to-we-not, Soka-tal-ko, and Rain Falling from a Passing Cloud.

From Shore to Basin and Range

The home of Lokout’s family lay in present-day Yakima County around the towns of Wenas, Selah, and Naches. The family made frequent trips to Puget Sound to visit family, exchange goods, and gather food. One destination was the Nisqually River, where Lokout’s aunt lived, and Fort Nisqually, the first European trading post on Puget Sound. Few records of those days remain.

Mary Moses (?-1939), though, a half-sister of Lokout and Qualchan, recalls a trip east of the Rockies that her family made in 1847 or 1848 with the family of old Chief Sulktalthscosum. Mary and Lokout were between 8 and 12. The family met some friendly Kalispell Indians who were gathering roots. They stuck together, rode to the bison-hunting grounds, killed many bison, and were ready to ride home when they ran into a camp of territorial Blackfeet Indians. A seven-day battle ensued, and young Lokout’s grandfather died from a Blackfeet bullet. In later years Lokout’s band would sojourn for months or years to the Great Plains both to hunt and to fight.

Ordeal on the Naches Trail

While Lokout was honing his skills as a warrior, he had a bad experience in 1853 with Theodore Winthrop that deepened his hostility to the "Bostons" (Americans) who already were occupying his homeland. At Fort Nisqually the traveler and writer Winthrop arranged for the guide services of Lokout, Chief Owhi’s son, who was then some 19 years of age. The destination was Fort Dalles where Winthrop was to meet traveling companions. Lokout was going by the name Loolowcan, he admitted 53 years later to Yakima rancher, historian, and legislator Andrew Jackson Splawn (1845-1917). Winthrop, who believed his Yankee ethnic group and culture to be superior to Lokout’s, gave Lokout a rather derogatory report in his posthumously published memoir of the journey. Still, the book remains the best record of Lokout’s demeanor and appearance.

When first they met at Fort Nisqually, Lokout was gambling among a group of other Indians. “Squalid was his hickory shirt,” Winthrop noted, "squalid his buckskin leggings, long widowed of their fringe. Yet it was not a mean, but a proud uncleanliness, like that of a fakir, or a voluntarily unwashed hermit" (Winthrop, 49). Despite Winthrop’s scorn, he admitted that "there was a certain rascally charm in his rather insolent dignity, and an exciting mystery in his undecipherable phiz [i.e., physiognomy]" (Winthrop, 50). Winthrop also acknowledged that young Lokout “had been selected for his knowledge as a linguist and his talents as a guide ..." (Winthrop, 54).

When Lokout met another Indian friend or “brother” on the trail, he displayed his boyish side. The two Indians

"laughed sunset out and twilight in, finding entertainment in everything that was or that happened — in their raggedness, in the holes in their moccasins, in their overstuffed proportions after dinner, in the little skirmishes of the horses, when a grasshopper chirped or a cricket sang, when either of them found a sequence of blackberries or pricked himself with a thorn — in every fact of our little world these children of nature found wonderment and fun. They laughed themselves sleepy, and then dropped into slumber in the ferny covert” (Winthrop, 64).

Later, after overcoming the rigors of Naches Pass, Winthrop admitted with admiration, “He has memory and observation unerring; not once in all our intricate journeys have I found him at fault in any fact of space or time” (Winthrop, 122). The travelers’ limited verbal exchanges took place in the trade patois of the Northwest known as Chinook Jargon.

Like other Indians of his time, Lokout claimed a totem or tamanous, a spirit power to pilot and protect him. His was the wolf, Talipus, "a very mighty demon," Winthrop wrote. This animal is “a link between himself and the rude, dangerous forces of nature. Loolowcan has either chosen his protector according to the law of likeness, or, choosing it by chance, has become assimilated to its characteristics" (Winthrop, 122).

Winthrop continued, “Wolfish likewise is his appetite; when he asks me for more dinner, and this without stint or decorum he does, he glares as if, grouse failing, pork and hard-tack gone, he could call to Talipus to send in a pack of wolves incarnate, and pounce with them upon me"(Winthrop, 123). On the journey, Winthrop often felt intimidated by Lokout, especially at night, the more so when their relationship began to fall apart.

The bad experience reached its peak for Lokout when Winthrop roused him early one morning with a kick. The kick he delivered, Splawn opined, was "deadliest of insults to an Indian. It is a wonder that Lokout did not knife him then and there" (Splawn, 60n.). The road-builders’ camp where they were sleeping likely inspired the coup de pied; the nearby whites emboldened Winthrop to cruelty.

Years later Lokout recalled the incident for Splawn. Lokout reported of Winthrop:

"I did not like the man’s looks and said so, but was ordered to get ready and start. He soon began to get cross and the farther we went the worse he got, and the night we stayed at the white men’s camp who were working on the road in the mountains, he kicked me with his boot as if I was a dog. When we arrived at Wenas Creek, where some of our people were camped, I refused to go farther; he drew his revolver and told me I had to go with him to The Dalles. I would have killed him only for my cousin and aunt. I have often thought of that man and regretted I did not kill him. He was me-satch-ee (mean)" (Splawn, 130).

The ensuing breakdown in relations propelled Winthrop later to meditate on the virtues of his own race: "No war is in our hearts, but kindly civilizing influences. If you resist, you must be civilized out of the way. We should regret your removal from these prairies of Weenas, for we do not see where in the world you can go and abide, since we occupy the Pacific shore and barricade you from free drowning privileges. Succumb gracefully, therefore, to your fate, my representative redskin" (Winthrop, 140).

Once Lokout reached his people in the Wenas Valley, he had suffered enough abuse and refused to go farther. Winthrop refused to pay him during his desertion, but "'I no die for lack of it,' said Loolowcan, with an air of unapproachable insolence" (Winthrop, 148). Winthrop rightly reasoned that Lokout’s pay had been dispensed already -- "a journey home and several days of banqueting ... ." (Winthrop, 150). Winthrop further wrote, "I fear that the traitor escaped unpunished, perhaps to occupy himself in scalping my countrymen in the late war" (Winthrop, 153).

Lokout did continue to fight the incursions of the Americans. But Winthrop failed to acknowledge how his abusive behavior estranged Lokout and contributed to the combative spirit that would mark his Indian guide’s early and middle adult years.

A Pitched Resistance

"Early in 1853," according to Eastern Washington jurist William Compton Brown, "the fact became apparent to the Indians that the occupation of their country by the Americans was at hand" (Brown, 79). The treaty wars would begin in 1855.

Lokout, in the prime of his life at 21, had grown into a warrior after a series of treaties forced upon the tribes radicalized them. The first governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), according to Brown, started the war in 1855 through “the illegally presumptuous stunt of publishing in the Olympia and Portland newspapers a declaration to the effect that the treaties negotiated at Walla Walla had cleared the way for immediate entry of the whites upon all Indian lands east of the Cascade Mountains, other than those expressly mentioned as held out for Indian reservations” (Brown, 131). Those treaties in fact had to be ratified first by the U.S. Senate and the president, and ratification did not occur till April 18, 1859.

Lokout and Qualchan

But the flood of miners and non-Indian settlers had already begun, hastened by the discovery of gold on lands set aside for the Yakama Tribe. With that unwelcome and illegal invasion, Yakama hostility began to burn with a steady flame. The tribes united under Chief Kamiakin (ca. 1800-1877), but Lokout’s brother Qualchan led the charge in many fights. Brown called the brothers “the Castor and Pollux of Yakima Indian history” (Brown, 215), an allusion to twin brothers Castor and Pollux of Greek mythology. The brothers shared Leda as a mother -- Castor the mortal son of Tyndareus, the king of Sparta, Pollux the divine son of Zeus -- and they were associated with horsemanship. When Castor was killed, Pollux asked Zeus to let him share his own immortality with his twin to keep them together, and Zeus transformed them into the constellation Gemini.

Qualchan and Lokout, hailing likewise from a family that prided itself on its horses, shared Owhi as father but had different mothers. They learned the art of open warfare from Plains Indians. “[Yakama] Indians fought individually instead of in concerted groups,” archeologist Stephen B. Emerson has written, and "were proficient at shooting from horseback, whereas most of the soldiers had to dismount, fire, and resume pursuit" (Emerson).

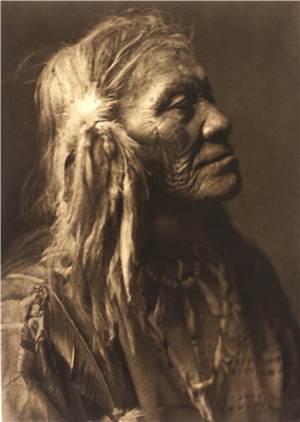

In the Indians’ guerilla style of fighting, which included night raids and horse rustling, grass fires and scalping, these brothers became partners in “one of the greatest federations of Indian tribes ever recorded in history” (Splawn, 87). Whereas Qualchan died prematurely -- due in part to the great renown that marked him as a target by the U.S. military -- Lokout lived a long and illustrious life and was immortalized in 1910 by Edward S. Curtis in a gorgeous orotone profile photograph that would be reproduced decoratively for decades. Due to his martyrdom, though, Qualchan has eclipsed Lokout in historical renown.

Incident on the Naches River

One well-documented incident in the treaty war embodies Lokout’s spirit as a warrior. In May 1856, on the banks of the Naches River, some 400 Indians had closed in on a camp of Col. George Wright (1803-1865) and were set to besiege it. Yakama leader Owhi opposed the more militant Kamiakin and championed a plea for peace rather than continue the fight. A disgusted Kamiakin rode away and took half the warriors with him, never to return to his home. Lokout, although he remained at the side of his father, Owhi, was disgusted likewise but more ashamed.

"Mounting his horse," according to Splawn, "he said in a loud voice, 'I am the son of a chief and a tried warrior. After hearing my father talk, I do not want to live. I will swim the river on my horse. I will go to the soldiers’ camp and be killed'" (Splawn, 60). Prior to this resolution by Lokout, Wright had promised to gun down any armed Indian who approached his camp. Lokout went armed anyway, not with a gun but with a bow and quiver, swimming his horse at first to an island in the Naches River. After resting a moment, "he then swam on to the other shore which was lined with blue-coated soldiers" (Splawn, 60) There he delivered a speech to Wright about how his father wanted peace but he wanted war. He told Wright he was ready to die for the cause, which would in turn spur his father, Owhi, to continue the fight.

Here is the speech Lokout delivered to Wright, again according to Splawn, who interviewed him at length in 1906: "If I am killed, my father and brother will fight on, which is what I want them to do. I have one life to give and am ready to give it now, that war may continue until the whites are driven from our country. If I live, Ow-hi will fight no more. You now know the object of my coming. I am waiting" (Splawn, 60).

He swam back with a tobacco gift from Wright, then back again the next day to Wright with a message from his father: "Owhi is glad to quit fighting. His people are tired and poor. It seems when he drinks water or eats food that it tastes of blood. He is sick of war" (Splawn, 60). If the language of these speeches smacks of Patrick Henry’s "Give me liberty or give me death," chalk it up to the translation, exalted like most period paraphrase.

Warrior at War

The peace did not hold; Owhi's sons would not surrender. Lokout persisted in the fight. Splawn claims that he was active in battles in Toppenish where Major Granville Haller (1819-1897) was defeated, at Union Gap "when they fought Major Rains; also at the battle of Walla Walla, when the great chief Pe-peu-mox-mox [Peo Peo Mox Mox, d. 1855] was killed; also participated in the attack on Governor Stevens, a few miles above the present city of Walla Walla; was in the fight that defeated Colonel Steptoe in the Palouse country; was in the attack on Seattle in 1856, and again at Connell’s Prairie" (Splawn, 126). What is more, Splawn wrote, Lokout was at the battle of Little Big Horn, "when Custer and all his men were massacred" (Splawn, 126).

Some of these accounts came from Lokout himself, making corroboration impossible, but other histories bear out key details. "When Col. Steptoe was defeated in 1858, Lokout was one of the Indian sharpshooters selected by Ka-mi-akin to pick off Captain O. H. P. Taylor and Lieutenant William Gaston, saying, 'These two men must die if we are to win,' after which these officers were special targets of the unerring rifles. Thus fell two gallant men, victims of an ill-advised expedition” (Splawn, 126). Other histories also address Lokout’s skill with a rifle and his fierce resolve to repel the invaders.

Less often acknowledged is his keen capacity for self-preservation. The hollow or gouge in Lokout’s forehead became a signature of his valor and tenacity. In hand-to-hand combat against the forces of Governor Stevens near present-day Walla Walla, Lokout killed one volunteer solider, but was enduring such pain that "with two bullet holes through his breast [he] fainted. A volunteer, in passing, struck him with his gun stock in the forehead, deeply gouging his skull and leaving him for dead" (Splawn, 80). It was surely intended as a deathblow. "But Lo-kout was not dead. Fifty years after that fight, hale and hearty ... he came to visit me in 1906. His skull had a hole in it that would hold an egg. How he ever survived such an injury I do not know” (Splawn, 80). Despite the mix of hearsay and legend that sometimes imbues such reports, photos bear out Lokout’s deep forehead crease.

Lokout was also a player in a pivotal event that turned the war. On September 25, 1858, Col. George Wright -- on an expedition to punish the Yakama, Palouse, Spokane, and Coeur d'Alene tribes after they had defeated Lieutenant Colonel Edward Steptoe (1816-1865) -- tricked Chief Owhi into his camp and captured him. Wright then allegedly had word sent to Qualchan that his choice was to surrender or see his father hanged. The following day Qualchan "appeared carrying a white flag. He wore Yakama finery of beaded buckskin and he rode his best horse. His wife carried his rifle and his brother Lokout accompanied them” (Wilma). Within 15 minutes Qualchan had been hanged. His brother and favorite wife knew their very lives were on the line.

What happened next remains disputed. Many say that a Spokane Indian vouched for Lokout as a tribal member and secured his release, while others say that Lokout wrestled a noose from his neck to mount Qualchan’s war horse and escape. Some say Qualchan’s wife grabbed a saber and slashed her way to freedom, while others say she plunged a defiant lance in the ground and left it quivering after Wright released her. Whatever happened that day, on the shore of what later came to be named Hangman Creek, it was the beginning of the end of the war.

In succeeding weeks or years, Lokout would marry his brother’s widow -- variously named Mary, Whisto, Swista, Whist-alks, Tat-sa-misa-quest, and Walks in a Dress (1838-1909). He lived with her for decades on the Spokane Reservation near the confluence of the Spokane and Columbia rivers.

The Missing Years

If Lokout actually fought in the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, it might have been his last hurrah as a warrior. By then he was about 42. He reportedly told his wife that he was done fighting. He enrolled in the Spokane Tribe by virtue of both his wife's and his mother's bloodline. Thirty years later, he would conduct long interviews with Splawn, who was researching for his book Ka-mi-a-kin: Last Hero of the Yakimas, and with Edward S. Curtis, whose documentary record of the tribes entails voluminous written transcripts as well as photos. Lokout became a living resource for historians, as did his half-sister Mary Moses, who flourished well into her second century, following the death of her husband, the Columbia leader Chief Moses (1829-1899).

Key research by A. J. Splawn helps to measure the involvement of Lokout in the culture clashes that were closing the Northwest frontier in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Splawn was lucky to find the guide who had deserted Winthrop 53 years before. Asked if he was Loolowcan of that journey, Lokout quickly rose to his feet and, "with flashing eyes, he said, ‘Yes, I was then Loolowcan, but changed my name during the war later'" (Splawn). His smoldering anger flared anew. By the time of the 1906 interview, Lokout was living a quiet life with his wife near historic Fort Spokane. Many photos would portray him in the following years.

During his clash with the white militia, months after his brother was killed in 1858, Lokout had been left for dead on the battlefield. We may wonder with Splawn how he managed to survive that deathblow to the skull. Even if the trials he endured in guiding Winthrop were not enough to make a warrior of him, this ordeal certainly made an impact on his dedication to the cause of fighting white incursions.