Platted by water engineer Walter Granger (1855-1930) in 1893, Sunnyside was established next to the Sunnyside Canal, which brought irrigation to the shrub-steppe landscape of the Yakima Valley. Around the turn of the century, the townsite went into the hands of creditors, after which members of the German Baptist Progressive Brethren Church settled there to form the Christian Cooperative Colony. They bought the townsite, and formed a community dedicated to Christian living and ideals. Irrigation helped to make Sunnyside an important agrarian hub of the Yakima Valley. The demographics of the town shifted as agricultural workers found work in the area and by 2010, 82 percent of the 15,858 residents were Latino.

Early Days

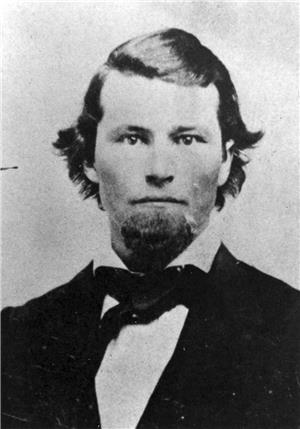

The earliest inhabitants of the area around Sunnyside were bands of the Yakama Indian Nation that inhabited Yakima Valley, fished the Columbia River, and gathered food from the land. Ben Snipes (1835-1906), a cattle rancher, was one of the first Euro-Americans in the valley in the 1850s. Snipes used the area around Sunnyside largely for cattle pastures and drives into the 1880s. One of Snipes's cowboys, O. R. "Ren" Ferrell, bought Snipes's original ranch in 1879, and was the first settler in what is now considered Sunnyside.

Walter Granger founded Sunnyside in 1893. He first came to the area in 1889 as a Northern Pacific Railroad water engineer, and to irrigate the area, conceived the plan for the Sunnyside Canal. The canal would bring water from the Yakima River to the Yakima Valley, allowing the semi-arid shrub-steppe landscape to become a fertile agricultural center for the state. In Courage and Water, Granger is quoted as saying:

"In 1889, at the insistence of friends, I had come from Montana to look over the contemplated Sunnyside Irrigation Project. One June morning, accompanied by a guide, I left North Yakima driving through the 'Gap,' Parker Bottom and out into the Valley. A few miles farther down we ascended Snipes Mountain and traveled along its summit, the better to view the country on either side. When we reached the lower, or east end of the ridge, the vast area of practically level land below us, plainly indicated that we were in the heart of the region. As I gazed on the scene. [sic] I then and there resolved that a city should some day be built at the base of the mountain, for the site was ideal" (Courage and Water, 13-14).

By 1893, Granger had made good on his word and Granger's company had surveyed and platted Sunnyside. Paul Schulze was president of both the townsite and The Northern Pacific, Kittitas, and Yakima Irrigation Company. Schulze first suggested the name "Mayhew" for the new town. William Cline, whom Schulze was trying to woo to the town, strongly objected. According to Courage and Water, Cline said:

"It's bad enough to encroach upon the coyotes, jackrabbits and rattlesnakes. It is foolhardy to build a store miles across a trackless sagebrush waste on the opposite side of an unabridged river. It is unworthy of any sane person to hope for success with but so pitifully few customers and the nearest one miles distant — and all broke. But even if I was so demented as to assume such colossal hazards, I just simply will not dare the Fates by moving to any place named 'Mayhew'" (Courage and Water, 1).

Cline ended up agreeing to settle in the much more optimistically named Sunnyside, but apparently didn't object to building a store on Mayhew Street, now Edison Avenue. The store officially opened January 2, 1894, becoming the first building in Sunnyside. Unfortunately, there weren't a lot of customers flocking to it, as the area had fewer than a dozen families. The financial Panic of 1893 had forced the Sunnyside Canal into the hands of creditors, and interest in the area shrunk. Eventually, the entire townsite was foreclosed upon, and the Philadelphia Securities Company took possession. Paul Schulze, accused of financial mishandling, committed suicide.

Though they were few (about a hundred residents in 1894), the town had quite the characters. There was R. D. Young, who became "Sunnyside's first weather observer, a duty which voluntarily assumed without remuneration of any kind, for fifteen years" (Courage and Water, 16). Joseph Lannin built the first "plastered and painted" house in town, and became the Justice of the Peace while also creating the town's first library (Courage and Water, 16). There was David McGinnis, an agent for the townsite company, who so believed in Sunnyside's promise that he earned the nickname "Ten-Acre McGinnis" for claiming that 10 acres of the fertile dirt could support any family (Courage and Water, 17).

Clean Living in Sunnyside

But real salvation for the town came in the form of those who believed strongly in salvation itself. Scattered members of the Progressive Brethren Church (an offshoot of the German Baptist tradition, and sometimes called Dunkards) were looking to establish a community dedicated to Christian living and belief. They eventually settled on Sunnyside -- no doubt lured by the appeal of the nearby Sunnyside Canal, which promised agricultural self-sufficiency. The Christian Cooperative Colony was formed, and strict rules of residence were imposed to keep Sunnyside on a clean path. The group bought the townsite, just to ensure any enforcement had teeth. As Stephen J. Harrison, one of the town founders, bluntly phrases it: "In order to control the moral influences of the community we decided that it would be necessary to purchase the townsite of Sunnyside" (Lyman, 908).

There would be no drinking, gambling, or prostitution on the townsite, lest you want to lose your property. Weeds growing on a lot could get an owner unceremoniously dismissed from town. For 35 years, until the Volstead Act of 1933 was passed, there were no alcoholic beverages sold in Sunnyside. The new atmosphere of the town attracted many observant religious people; dancing was not strictly banned but was discouraged, and for years a curfew ordinance required unaccompanied minors to be home by 7 p.m. The town became known as "Holy City" for its strict adherence to clean living.

The town continued to grow, and by 1902, there were 178 school-age children in the school district. Soon, a new high school was being commissioned. And technology came pretty early to Sunnyside: 40 telephones had been installed in town by 1902, thanks to the Christian Cooperative Telephone Company. One requirement for getting a phone was that you must owe stock in the company, which sold for $50 a share. If you used profanity over the line, your service was cancelled.

Incorporation

With the growth of the town, incorporation was soon at hand. A census at the time revealed that 314 people resided in Sunnyside, enough to meet the 300-person requirement for incorporation. A petition for an incorporation vote gained 64 names, and an election was held September 2, 1902. Forty-two residents voted to incorporate, with only one holdout against. The County Auditor of Yakima County officially certified the vote on September 16, 1902.

During the same election, James Henderson, the town druggist, was elected mayor. William Bright "Billy" Cloud, C. W. Taylor, William Hitchcock, Joseph Lannin, and George Vetter were elected to the city council. J. B. George was elected town clerk and treasurer. During the first council meetings in September and October, the officials got down to business. The clerk's salary was established at $50 a year, and a poll tax was passed: $2 a year for every male over 21, with the funds going to street improvements.

Beginning to Thrive

In 1906, the Northern Pacific railway line finally arrived at Sunnyside, much to the delight of the town. A big barbeque was held, and 3,000 people came out to see the first train pull into the station. Unfortunately, the car stopped nearly half a mile away; it was much heavier than any train tested so far, and its weight caused the tracks to sink into mud. The tracks were quickly reinforced, however, and service soon commenced. A daily trip was made back and forth between Sunnyside and North Yakima (as Yakima was then called).

And while Sunnyside grew, the canal that would take its name also was coming into existence, and slowly changing the landscape of the area. After the canal was forced into receivership in 1895, Walter Granger still managed to keep construction crawling on the irrigation system. By 1900, the Washington Irrigation Company purchased the Sunnyside Canal, and extended it through Prosser. In 1905, the Federal Bureau of Reclamation purchased the canal from the Washington Irrigation Company. It then became part of the federally funded Yakima Project, which brought irrigation to the whole of the Yakima Valley.

By the early twentieth century, Sunnyside's now-irrigated land was fertile, and the area was growing along with the alfalfa and apples. A 1909 advertisement in the Seattle Times (partly sponsored by Sunnyside's Commercial Club) beckoned residents to the little town, which now boasted nearly 1,000 people. Promising a great haul for farmers, the ad assured that vegetables, potatoes, timothy hay, cattle, sheep, and fruits accounted for the "five to twenty carloads of farm products" shipped out of Sunnyside daily ("Sunnyside, the Town That is Different").

Sunnyside's relentless piousness continued, and December 31, 1915 -- the first day of Washington state's prohibition law of alcoholic beverages -- proved to be just another day for the dry town. When the first beer was finally sold legally in Sunnyside in July 1934, Sheller says in Courage and Water that "it seemed entirely out-of-place to those who had lived in Sunnyside since its early days ... but with it came a compensating sensation of release" (Sheller, 235).

In 1917, Sunnyside had outgrown some of its rural artifices. In late 1916, according to Sheller's Courage and Water, Billy Cloud declared, "If I was Mayor of this town, I'd pave these mud-wallow streets" (Sheller, 198). Cloud got himself elected the next year, and made good on his promise. Sunnyside's paving project was completed in 1917 at a cost of $62,629.45.

A Center of Agriculture

The Great Depression hit Sunnyside hard, as it did a lot of agricultural areas. In 1929, potatoes were being sold for $125 a ton. Only a year later, they had plummeted to $14 a ton. In 1919, the Sunnyside irrigation area was producing $167.07 per acre in crop value. In 1930, the yield was $53.41 per acre. However, by 1933 the value of agricultural products in the area had increased by a third, and continued climbing.

As early as 1911, 900 tons of tomatoes were processed into catsup at the Sunnyside Cannery. Food processing grew in the area, and by the mid-twentieth century national manufacturers of jams and jellies had established processing plants. By 1945, the town was also home to Upland Wineries, one of the state's first -- and largest --wineries.

In 1947, Sunnyside became the first city in Washington state to adopt the city manager form of government. It continues to use the system to this day, and the seven members of the Sunnyside City Council appoint the city manager. As of 2013, 53 towns in Washington have a council-manager system.

Residents in the Sunnyside area voted to create a port district in 1947. By 1972, the Port had begun to build the Industrial Waste Water Treatment Facility on the site, designed to treat effluent from food processing and manufacturing. By 2009, 17 companies were taking advantage of the Industrial Waste Water Treatment Facility.

The Latinos of Sunnyside

Sunnyside's population continued to grow as the agricultural area thrived. Between 1970 and 1980, the population ballooned from 6,751 to 9,225. And with that expansion came a shift in demographics, as the Latino population found work and homes in the Yakima Valley. By 1975, the Sunnyside School District had 35 percent Mexican American enrollment.

That same year, the federal Office of Civil Rights found the district in violation of several parts of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Some of the accusations listed were that minority students were not given "instructional programs" related to the language and culture of the minority pupils, a lack of faculty to mirror the racial enrollment of the district, and "discriminatory assignment" of Mexican American children to special education classes ("Schools Charged With Discrimination"). By 1976, Sunnyside School District had an anti-bias plan drafted and accepted by the Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

Demand for bilingual services was so high by 1978 that a Spanish-English educational television channel was added to the Sunnyside lineup. The 12 hours of six-day-a-week programming was geared toward migrant children, and the Mid-Valley Cable Company, based in Yakima, donated the channel. The televised bilingual education programming was one of the first of its kind in the nation.

The passage of the Immigration Reform and Control Act in 1986 had far-reaching significance to immigrants in Sunnyside and the Yakima Valley. With the passage of the act, immigrants in the United States prior to 1982 were granted amnesty, but employers who hired illegal workers after its passage were severely punished. Undocumented workers were left desperate to prove that they had worked and lived in the area prior to 1982, or were forced to hide from Immigration and Naturalization Services as crackdowns began occurring.

Wine and Milk

Even at the cusp of the twenty-first century, Sunnyside remained quietly dedicated to the Christian ideals the town originally espoused. In 1989, only three taverns were in the town of about 11,238. In 1987, when it was proposed to rename part of Old Yakima Highway "Wine Country Road," the City Council received a petition of 200 signatures asking that they reconsider extoling alcohol through the name. The issue was dropped, and nearby Grandview took the name for one of its roads.

Darigold Inc. infused the area with money and jobs in 1990 when it chose Sunnyside for the site of its $22-million milk processing plant. The unemployment rate at the time was around 11.8 percent, and the Darigold project became the "largest single capital development" in the Sunnyside area ("Dairy Cooperative…"). By 2013, Darigold had made the decision to begin a $22-million expansion of the Sunnyside plant, adding 125 jobs to the area.

At the 2010 census, Sunnyside had 15,858 residents. 82 percent of the population is Latino.