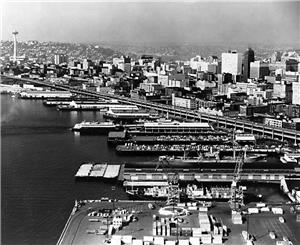

On April 20, 1965, John Graham and Company submits its Technical Report on the Seattle Central Waterfront Development, a redevelopment plan commissioned by the City of Seattle, the Port of Seattle, and private pier owners. For several decades, changing shipping practices, including the shift to larger ships and containerized freight, has led to fewer uses for the central waterfront's finger piers. As activity has declined on the central waterfront, between Yesler and Broad streets, the city has struggled with how to develop the space for new uses. City planners also want the waterfront to help revitalize the nearby central business district, which is struggling to maintain its economic vitality in the face of growing suburbs. The Graham plan calls for public investment in the redevelopment of piers and the construction of infrastructure to attract private development. The public investment element at the plan's core will be translated into a proposal for a waterfront park as part of the Forward Thrust parks measure, passed in 1968.

Responding to Change

Seattle, like many American cities after World War II, struggled to maintain its central business district as growing suburbs decreased the retail core's regional significance. Before the war Mosquito Fleet steamers, interurban streetcar lines, and in-city trolleys had carried customers to downtown Seattle as the hub of their transportation networks. Now automobiles, better local roads, and new regional highways allowed shoppers and business owners to choose from a wide variety of locations, including suburban shopping malls, to carry out their business.

Likewise, the formerly bustling finger piers along the waterfront gradually lost their tenants to larger and more modern Port of Seattle facilities on the northern and southern ends of Elliott Bay. Container operations needed longer piers for larger ships and more shoreline space for holding and moving containers. The central waterfront's steep seafloor and narrow shoreline limited how much freight facilities could expand there.

The flow of people and goods through Seattle shifted substantially between the 1920s and the 1950s and city leaders struggled to draw enough business to provide the tax revenues needed to run the city and attract new development. Because this was such a widespread problem in the United States, Congress incorporated funding for urban renewal in its Housing Act of 1949 and expanded the program in 1954. Urban renewal programs provided funding for the acquisition, demolition, and reconstruction of buildings in urban areas deemed to be blighted.

Cities had to adopt comprehensive plans that included "blighted" areas to apply for the funds. Seattle's existing comprehensive plan, adopted in 1956, did not address those areas specifically, so the city hired Donald Monson, a planner from New York, to prepare a plan for downtown that would amend the 1956 comprehensive plan. That plan was adopted in 1963 and it included recommendations for improvements to the downtown, including transportation improvements and a focus on replacing rundown buildings on the periphery of the central business district with new housing and commercial properties.

Detailed Plans for the Waterfront

Following the adoption of the Monson plan, the city hired planners to develop detailed plans for different parts of downtown. For the central waterfront, the city engaged John Graham and Company of Seattle. Graham took the larger concepts outlined in the Monson plan and developed a two-stage plan to redevelop and revitalize by 1985 the area extending north from the Washington State Ferries terminal at Marion Street to Bell Street, between the Alaskan Way Viaduct and the Elliott Bay shoreline.

Released in 1965, the Graham plan included proposed restaurants and entertainment facilities, such as an aquarium along the shoreline. A large park on a pier and a long esplanade along a marina would ensure public access to the water. None of the historic pier sheds would remain in the area bounded by Washington and Pike streets. Instead, parking lots, motels, a marina and related businesses, a boatel, and retail stores would occupy large piers covering major expanses of shoreline. A cableway, or gondola, between Pike Place Market and a park at the foot of Union Street would carry visitors up and down the hillside. Pedestrian ramps at Columbia, Marion, and University streets would carry people down the steep hillside below 1st Avenue and across the railroad tracks and Alaskan Way to an elevated pedestrian walkway along the shore.

Graham's planners wanted to shift cars away from the shoreline. Between Yesler Way and Pike Street, they proposed to realign Alaskan Way along the inland side of the viaduct and vacate Western Avenue along that stretch. At Pike Street, Alaskan Way would veer back to the shoreline and a new Western Avenue would continue up the hill below the Pike Place Market. In place of the relocated Alaskan Way, parking lots and a small street with bus stop turnouts would allow drivers easy access to the piers. As in Monson's plan, automobile access was given a high priority in an attempt to keep the area competitive with suburban areas and shopping malls.

The Graham plan required that the city purchase piers and redevelop them using public funds, then lease the piers and new buildings to private businesses to run the attractions and facilities. The report explained, "The City of Seattle must take the initiative in implementing the plan ... Once this development is launched, private investment is sure to follow" (Technical Report, 44).

The water was at the center of the Graham plan and each of its elements made use of the water to make the waterfront and the central business district more attractive. In the report, Graham wrote, "The long range plan for improvement of Seattle's Central Waterfront is based on the proven concept of creating a center of activity on the water itself, and surrounding this center, as well as other points of interest, with walks, open space, shops and restaurants, and finally, by providing good access and adequate parking space to accommodate a large number of visitors" (Technical Report, 30). He cited San Francisco's Fisherman's Wharf and Oakland's Jack London Square as examples of the types of city-led redevelopment projects that could rejuvenate waterfronts that had been left behind by changing shipping technology.

Park Bonds

When, in 1968, the city put a group of bond measures, known as collectively as Forward Thrust, before voters, the parks bond included a waterfront park. Although the Graham plan had proposed the park at the center of its plan area, between University and Pike streets, the bond measure only called for a park somewhere on the shoreline. City officials wanted to spend more time determining the best location and how the park could help stimulate development on the waterfront.

The park bond was approved and the Forward Thrust funding was used to hire Rockrise & Associates in 1968 to develop the concept and context for a waterfront park. That firm's proposal for the park, which it located between piers 55 and 61, incorporated the Graham plan's idea of integrating private enterprise into a publicly developed park area and envisioned that the initial public investment would stimulate private ventures in the area, such as an aquacircus, office buildings, hotels, and apartments. Waterfront Park opened in 1974.

The expected burst of private development did not materialize, but over several decades the waterfront slowly shed its industrial character as public amenities and private developments took over the old buildings and piers and filled them with shops, restaurants, offices, parks, and an aquarium. A mix of public and private developments also improved connections between downtown and the waterfront through the construction of hillside stairways at Pike, Union, and University streets.