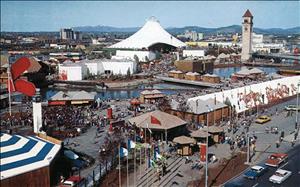

Expo '74, Spokane's World's Fair, was an international exposition held from May 4 to November 3, 1974, in Spokane. With a population of only 170,000, Spokane was the smallest city ever to hold a world's fair, yet it attracted almost 5.2 million visitors. The theme was the environment. Ten countries, including the Soviet Union, Japan, and the United States, along with many states and corporations, hosted pavilions on the 100-acre site. The original impetus of the fair was to clean up and reclaim the land alongside the mighty falls of the Spokane River, which for decades had been clogged with railroad tracks, trestles, and warehouses. Under the leadership of King Cole (1922-2010), a veteran of urban renewal projects, Spokane made the audacious decision to host a world's fair and then convert the downtown site into a public park. After the fair closed, the site was revamped to become Riverfront Park, today the city's downtown showcase and gathering spot. David H. Rodgers (b. 1923) Spokane's mayor at the time, said, "Reduced to its essentials, we gave a great big party and the rest of the world came and paid the bill" (Youngs, 503).

Ugly Tracks and Trains

In the middle of the twentieth century, Spokane desperately needed to solve two daunting urban problems. First, a set of railroad tracks bisected the heart of the city, creating constant traffic jams.

"As long as you have a train running right through the middle of downtown, stopping traffic, you are pretty much a small town, hick outfit," said Neal Fosseen (1908-2004), Spokane's mayor in the 1960s (Youngs, 162).

"Trains and automobiles were all mixed up," said King Cole. "Those trains would be moving freight and you would get your car down on Howard Street at one of those train crossings. And you’d see the end of the train coming, coming, coming, coming and just as you're ready to cross -- load her up and get going -- the whole thing stops and goes backward again. This is how it was. It was silly that this was happening in this day and age, but it was happening every day, all the time" (Youngs, 162).

These tracks were sometimes stacked high on ugly steel viaducts, which created the second, related problem. The tracks and the big depots that served them effectively cut downtown Spokane off from its most spectacular natural asset: the rushing Spokane River and its white-foaming Spokane Falls. Spokane people jokingly called the railroad trestles the "Chinese Wall" (Youngs, 107).

Spokane and its Falls

The falls had originally been Spokane's main attraction. The Spokane Indians established salmon camps at its base and the earliest settlers were attracted to its majesty and waterpower. In 1908, the famous Olmsted Brothers Landscape Architecture firm devised a plan for Spokane's parks in which they noted that the falls were "a tremendous feature of the landscape, and one which is rarer in a large city than river, lake, bay or mountain" (Olmsted). They noted sardonically that the area around the falls had already been "partially 'improved,' as one might ironically say," but they expressed doubt whether anybody could be proud of these "improvements," which consisted of tracks, rail yards, and warehouses (Olmsted). They predicted that one day the city would come to its senses and reclaim the area for a park.

That day was about to arrive. In 1959, a group of downtown business and property owners started a group called Spokane Unlimited, with the goal of revitalizing Spokane's downtown. In addition to the railroad tangle, Spokane's downtown was facing other problems faced by cities across the nation in the 1950s. Stores were moving out to malls and people were moving out to the suburbs. The city's big downtown interests -- notably Washington Water Power, the big downtown banks, and the Cowles Publishing Co., which owned the two daily newspapers -- helped Spokane Unlimited raise enough money to commission an urban renewal plan from EBASCO Services Inc., a New York consulting firm.

EBASCO's 1961 report called for, among other things, removing the "Chinese Wall" of trestles and opening up the Spokane River and its midstream Havermale Island "as integral parts of downtown" (Youngs, 118). The report advocated "recapturing the beauty and attractiveness of the central business district's natural setting" (Youngs, 118). According to The Fair and The Falls, J. William T. Youngs's indispensable history of Expo '74, many Spokane residents had, astonishingly, "forgotten the river was there" (Youngs, 118). EBASCO suggested accomplishing the work in five-year increments, ending in 1980.

King Cole and His Vision

How did EBASCO propose to accomplish this? Not through a world's fair, a concept far beyond anyone's imagination in 1961. Instead, the firm recommended passing general obligation bonds, a gas-tax increase, and acquiring federal urban renewal money. All of these proved to be difficult propositions. Spokane voters soundly defeated two bond issues in 1962 and 1963. The leaders of Spokane Unlimited scrambled for a new direction, and in 1963 they decided to hire a professional executive with urban renewal and planning experience, King Cole. Cole had worked on urban renewal projects in the California cities of Sacramento and San Leandro, and his goal in Spokane was to, somehow, turn the EBASCO plan into reality. He threw himself into the role with characteristic perseverance.

He recognized that Spokane's voters were unwilling to be dictated to by downtown moneyed interests. So he began by creating a citizen's group, Associations for a Better Community (ABC), as a grass-roots partner to Spokane Unlimited. As the 1960s progressed, the community began to coalesce around the idea of riverfront beautification in general, and, specifically, turning the railroad-choked Havermale Island into open, public space. Yet the obstacles were daunting. The property was "controlled by 16 different owners" (Official Program, 15). The biggest owners were, of course, the railroads. When the railroads were first approached about handing over their land to the city, one railroad executive was shocked to realize that the city was, in essence, asking for the equivalent of an $18 million donation (Youngs, 163). The chief executive officer of the Milwaukee Road said, "If I gave away that much valuable property, it would probably be my last act as CEO" (Rodgers, 31).

In the meantime, Spokane had been thinking about holding a big celebration to commemorate the centennial of its founding in 1873. Maybe, they reasoned, that celebration could finance the riverfront restoration. In 1970, Spokane Unlimited commissioned a feasibility study from Economics Research Associates (ERA) of California. The report was sobering. It said the city would be throwing away money if it spent it on a strictly local centennial. The city might spend as much as $1 million, and end up with no downtown improvements to show for it. If Spokane really wanted to make lasting improvements, it must set its sights much, much higher, said the report. It should think about an international exposition. That way, the city could get federal and state dollars, attract visitors from all over the world, and end up with a completely transformed riverfront.

A Real Honest-to-God World's Fair

A member of Spokane Unlimited's five-person executive committee recalled listening to an ERA speaker as he broached the idea. The five men looked at each other and one of them finally said, "Well, it looks to me like what we’ve got to do is have an Expo" (Young, 172).

Actually, this audacious idea was already at the back of King Cole's mind, after a conversation he had with Joe Gandy (1904-1971) who headed up Seattle's Century 21 World's Fair in 1962.

"Am I crazy to think about something like this for little Spokane?" Cole asked Gandy (Youngs, 69).

"No, you're not, you're right on target," Gandy said. "Little old Spokane is just about where Seattle was, relatively speaking, back in the '50s when we started thinking about a world's fair -- and we pulled it off" (Youngs, 170).

Spokane Unlimited immediately became excited about the idea of a "real, honest-to-God world's fair," with a timely theme: the environment (Youngs, 172). Not only was the environment a hip and progressive topic, but it also seemed an ideal theme for a fair with a spectacular waterfall running through its middle. Yet the leaders had to make certain that the idea was practical. No city as small as Spokane -- which had a population of about 170,000 -- had ever hosted a world's fair.

They commissioned ERA to make discreet inquiries to the Bureau of International Expositions in Paris, which governed such events. The bureau's head indicated that a Spokane exposition was "not only possible, but a damned good idea" (Youngs, 172). They also commissioned ERA to do a further study on the economics and logistics of an exposition. That report, issued in September 1970, was a ringing endorsement of the idea. It said that a world's fair would, in one monumental effort, solve the city's urban renewal problem and "recapture the natural setting of its falls" (Youngs, 174). The target date: 1974.

The Race Begins

Then the race began to get a world's fair funded, planned, publicized, built, and opened in less than four years. King Cole would later jokingly summarize the three phases that a big project like this must endure:

1. "You've got to be kidding!"; 2. "My God, the dummies are going to do it! They're going to ruin us!"; 3. "They’re doing it and it's working. Gee, that was a great idea that I had" (Youngs, 178-179).

The centennial committee was transformed into the Expo '74 Corporation, which quickly extracted pledges of $1.3 million in start-up money, mostly from local businesses. Corporation members then went to the Washington State Legislature, whose support was crucial if the idea was to advance at all. In March 1971, the legislature easily passed three bills -- one to form an Expo Commission, one to authorize an Expo surtax on corporate licenses and fees, and one to appropriate $7.5 million (later increased to $11.9 million) to build the Washington State Pavilion, which would later become the Spokane Opera House and Convention Center.

Winning votes at home proved to be more difficult. The city authorized a vote on a $5.7 million bond issue, which would pay for removing the downtown tracks and trestles and clearing Havermale Island. The money was not specifically for Expo '74, yet the vote was widely seen as referendum on the fair, since it would provide the fair's setting. Local opposition was vocal. Some people believed wealthy downtown interests were foisting the project upon the community; they took to calling it "Exploit '74" (Youngs, 290). Some feared it would be a financial fiasco; and others feared it would lead to growth and big-city problems. When the votes were counted on August 31, 1971, the bond issue had 57 percent approval, a solid majority, but agonizingly short of the 60 percent needed to pass.

The disheartened supporters believed they had two alternatives. Either they could abandon the fair altogether, or push through a temporary business-and-occupation tax. The B&O tax was traditionally anathema to the Spokane Chamber of Commerce and generally "about as popular as a skunk at a garden party," said one Expo backer (Youngs, 188). Yet this case was different, because the chamber and the big downtown businesses were solidly committed to Expo '74. In the end, all seven members of the Spokane City Council held their noses and voted for the B&O tax on September 20, 1971, despite the fact that four of them were facing re-election the very next day. The tax raised the necessary $5.7 million to tear out the tracks, open up Havermale Island and, in essence, make Expo '74 possible.

In October 1971, U.S. President Richard M. Nixon (1913-1994) gave Spokane's Expo '74 his official sanction. Then it needed to clear its "last and biggest" hurdle, a half-a-world away in Paris (Official Program, 17). Cole and the Spokane delegation went to the Bureau of International Expositions in Paris in November 1971. After lengthy but mostly cordial discussions, Expo '74 received the bureau's unanimous sanction as an official "special exposition." The Paris bureaucrats were apparently smitten with Spokane's "little old country town" humility and gumption (Youngs, 196). A Bicentennial-themed exposition in Philadelphia for 1976 was also approved.

In 1972, Washington's powerful Congressional delegation, led by Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson (1912-1983), Senator Warren Magnuson (1905-1989), and Representative Thomas Foley (1929-2013), painstakingly shepherded through Congress an $11.5 million appropriation to build the U.S. Pavilion. Back in Spokane, Expo backers and city officials pulled off a crucial coup: They convinced the city's three railroads to move. The Union Pacific, Milwaukee Road, and Burlington Northern donated 17 acres of land to the city, worth many millions, and consolidated their routes to tracks away from downtown. It took many months of tense negotiations, and a series of complex land swaps, but one of Expo '74's key goals had already been accomplished. "The Spokane River was now cleared of railroad steel" (Official Program, 18).

The two depots were also torn down -- all except for one iconic piece of the Great Northern depot. It was the 155-foot-tall clocktower, with its nine-foot-diameter clock face. It would immediately become one of the most-recognized symbols of the fair, and of the city itself. The city also purchased some land using urban renewal grants from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Inviting the World

That same year, President Nixon issued an official proclamation inviting the world to Spokane's Expo '74. Now, Cole's job was to convince the world to show up. He traveled the world and soon landed a big fish, the Soviet Union, which committed to a $2 million pavilion. This gave Expo '74 instant credibility and publicity, since the Soviet Union had not had a world's fair exhibit in the U.S. since 1939-1940.

In the end, it proved difficult to lure national pavilions to faraway Spokane, especially European nations. Expo '74 eventually landed Japan, the Republic of China (Taiwan), South Korea, Canada, Australia, Iran, West Germany, and the Philippines. It was a "disappointing return," yet it was offset by the fact that the Soviet Union's pavilion alone "covered more space than all of the foreign exhibits combined at Seattle's 1962 world's fair" (Youngs, 236).

Luring corporate pavilions proved to be easier. Ford, General Motors, General Electric, Eastman Kodak, Boeing, and the Bell Systems signed up for pavilions. So did the states of Oregon and Montana and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. In the end, Expo '74 would cover 100 acres, slightly larger then Seattle's Century 21 World's Fair in 1962, but less than a tenth the size of the New York World's Fair in 1964. The Expo '74 site, which included a broad stretch of riverfront as well as Havermale Island and Cannon Island (sometimes called Crystal Island), was formally dedicated in May 1972.

Preparations and Panic Attacks

The next two years were both tense and exhilarating, as the site was transformed from rail yard to mud pit to environmental showcase. The fair weathered a leadership crisis in the summer of 1973 when the U.S. Department of Commerce determined that the fair needed an experienced fair manager. They brought in a new general manager, Petr Spurney (b. 1935), a veteran D.C.-area exhibition manager and planner. King Cole remained as the fair's president, yet his role shifted towards his strengths: selling the fair to the world. He traveled the country, appearing on TV shows such as "The Merv Griffin Show."

With the May 1974 deadline approaching, new doubts began to surface about the city's ability to pull off the event. The Philadelphia Bicentennial Expo had already been cancelled, and some outsiders were skeptical that Spokane could pull off what Philadelphia could not. A few insiders were skeptical, too. Six months before opening, one of the backers came up to Cole, tears streaming down his face, and blubbered, "King, you’ve got to call it off, you're gonna bankrupt the town!" (Youngs, 342). Cole was unfazed, since he had been warned by Seattle's Gundy to expect exactly that kind of pre-opening panic.

Even comedian Bob Hope (1903-2003) was a bit skeptical several months before the opening. He had come to film promotional ads for the fair, and after a tour, he told fair officials, "It scares me when I see all that mud out there. Are you sure you'll be ready to open on time?" (Bowers, 12). They assured Hope, somewhat nervously, that everything was on schedule. Up on the clocktower, a huge countdown sign displayed the days left until opening. The number went down to single digits before all of the construction was finished, all of the sod was laid and all of the paving was done. Even the fair's executives had to pull a few all-nighters, right before opening, planting flowers in the garden beds.

An International Flavor

On May 4, 1974, President Nixon officially declared the fair open, in a ceremony attended by 85,000. Under normal circumstances, the president's presence would have been an unmitigated coup for Expo '74. When Nixon's visit was first announced, Cole said, "This is an outstanding way for our fair to be recognized, as we have been an underdog and people didn't think we could put it together at all" (Youngs, 374). But these were not normal circumstances. Nixon was deeply embroiled in the Watergate scandal that spring and was at the nadir of his popularity. Five days earlier, he had released partial transcripts of the damaging tapes that would soon undo his presidency. However, his visit was a public relations victory for Expo '74, because it ensured that the eyes of the world were on Spokane for opening day. About 1,200 journalists were accredited for the opening.

The opening day reviews were mostly positive. Expo '74 clearly benefited from low expectations. Cole overheard a conversation in which an Associated Press reporter complained to a colleague that "it's not as much fun as I thought it would be" because he had wanted "to make fun of this place, but this is too nice to do that" (Youngs, 396).

A subsequent AP story said, "Absent is any hint that Expo, as wags suggested, is a big country fair. It has a true international flavor" (Youngs, 395).

The Fair and its Pavilions

Attendance remained strong, averaging about 35,000 per day over the summer months. About half came from Washington state, followed by visitors from, in order, California, Oregon, Montana, and Idaho. Only around 10 percent came from foreign countries, and most of those were from nearby Canada, making the "world's" part of World's Fair seem to be an overstatement. However, by the fair's end an estimated 100,000 people from countries other than the United States and Canada had visited the fair.

And what did they see? Among the foreign pavilions, the behemoth was the 54,500-square-foot Soviet Pavilion. Visitors walked past a giant statue of Lenin's head and a 4,500-pound aluminum relief map of the USSR, into a maze of "myriad spotlights, Daliesque artificial trees, fountains, chrome, plastic bubbles and colored liquid coursing through miles of transparent tubing" (Hill). It was filled with dioramas and displays about topics from urban renewal to nuclear physics to forestry. The pavilion's message about the fair's theme, the environment, seemed to one New York Times reporter to be "a phantasmagorical statement of how Russia's magnitude, might and diversity overshadow such mundane annoyances as dirty water and unbreathable air" (Hill). And on top of everything else, the pavilion had three movie theaters, one of which showed trained bears playing ice hockey.

The U.S. Pavilion, housed in its iconic tilted vinyl canopy, had a different perspective, with "mountainous displays of how we abuse our intrinsically magnificent environment" (Hill). The main attraction was an IMAX movie showing stomach-churning views of the Grand Canyon, and high-speed motorcycle races. "Barf bags" were available for those who got motion sickness. The U.S. Pavilion was by far the biggest, covering 179,250 square feet, under a 14-story tall steel mast.

The Japan Pavilion featured a serene formal garden, yet dwelt on the country's many environmental horrors. The Republic of China's fan-shaped pavilion contained one of the fair's biggest hits: a multimedia show on a 180-degree screen, with "three movie projectors and 28 slide projectors" along with rear-screen projector to simulate "lightning, fireworks and a moonrise" (Youngs, 448).

Canada's exhibit was on the newly renamed Canada Island (formerly Cannon Island or Crystal Island). In fact, the entire island was Canada's outdoor exhibit, featuring playgrounds, Indian totem-carvers, and an outdoor theater, all to the roar of the Spokane Falls. Youngs called it "nearly perfect as a display in an exposition devoted to the environment" (Youngs, 447).

Visitors collected "passport stamps" from each country's pavilion. Despite the fact that only 10 stamps comprised a complete Expo '74 international set, it was virtually impossible to collect them all in one day, even on a weekday when the lines were short. One reporter noted that simply walking, at a fast pace, from one end of the fair to the other, took a minimum of 30 minutes.

Entertainments and Attractions

Meanwhile, there were dozens of other attractions. The largest corporate pavilion was the 13,000 square foot Bell System Pavilion, where children could make phone calls to Mickey Mouse, Snow White and other Disney characters. The Ford Pavilion was mainly about the outdoors -- and also about Henry Ford's love of nature. The domed Kodak Pavilion was about "photography's role in the study and preservation of the environment" (Bowers, 104). Both the General Motors and General Electric pavilions made the case that improved technology could reduce pollution. GM showcased its new emission control system -- as well as an electric two-seater car.

Washington had the biggest state pavilion, encompassing the new 2,600-seat Opera House and an extensive art gallery. It also housed one of the surprise hits of the fair, the Kino-Automat. This was a 400-seat theater that showed two Czech-filmed comedies in which the audience was allowed to vote, with buttons at each seat, on the direction of the plot at key intervals. One of the films was for kids, and "audience participation was certainly less inhibited in the children's version," because the kids tended to shout their instructions at the characters instead of just pushing the buttons (Bowers, 107).

An amusement area was tucked in the southeast corner of the park, including a $500,000 roller coaster from Germany and an 85-foot-tall Ferris wheel from Italy. For 70 cents a ride, visitors could hop on contraptions called the Universa, Himalaya, Roundup, and Apollo 11.

Two different kinds of rides, the Sky Rides, were people-movers. One was essentially a two-person ski chairlift, intended to transport people from one end of the fair to the other. The second was an enclosed Gondola ride that transported sightseers across the thundering Spokane Falls. The Gondola dropped so close to the falls that the windows were sprayed by the mist.

When fairgoers were asked 40 years later for their Expo '74 memories, many people vividly recalled the food, which included Danish aebelskivers, Russian borscht, and -- most popular of all -- sausages, schnitzel, and Munich beer at the Bavarian Beer Garden. Some pavilions, including the Soviet Union's, had their own restaurants serving that country's specialties. The rest of the food was served by vendors clustered in the Food Fair portion of the grounds. There, visitors could order Philippine Camaron Rebosado, Indian curry, French onion soup, or Japanese tempura.

As the official program pointed out, it was entirely possible to spend only $10 a day at Expo '74. The tally went something like this: $4 for admission, about 70 cents for a meal from a food stand (or $3 for a formal, sit-down dinner), a stein of German beer for 80 cents, a souvenir for a dollar or two, and $1.40 to ride the roller coaster and Ferris wheel. All of the exhibits and pavilions were free with the price of admission.

Music at the Fair

That left enough money left over to buy a ticket to one of the almost daily concerts, most of them in the newly built Spokane Opera House, part of the Washington State Pavilion. The concert lineup was probably the most truly international aspect of the entire fair. It included Marcel Marceau, Victor Borge, Margot Fonteyn and the London Ballet, Isaac Stern, Itzhak Perlman, The Moiseyev Dancers of Russia, The National Dance Company of Senegal, Festa Brazil, the Republic of China Acrobat Spectacular, the Georgian State Dancers and Singers, the Japanese Folkloric Dance Company, and the Royal Shakespeare Theatre with Sir Michael Redgrave and Dame Peggy Ashcroft.

The big entertainment names included Liberace, Bill Cosby, Bob Hope, Jack Benny, the Pointer Sisters, Helen Reddy, the Carpenters, Grand Funk, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Merle Haggard, Buck Owens, Van Cliburn, Chicago, Charlie Pride, and Ella Fitzgerald.

Mike Kobluk, Expo '74's director of visual and performing arts, had been a member of the Chad Mitchell Trio in the 1960s, so he used his connections to lure some of folk's biggest names: Harry Belafonte, Glenn Yarbrough, Gordon Lightfoot, the Irish Rovers, and John Denver. Denver was at the peak of his popularity -- "Annie's Song" hit No. 1 on the Billboard charts during Expo '74 -- and Denver incited a fan frenzy when he tried to tour the fair with Kobluk.

"He was just totally mobbed -- we got 200 yards into the site from our offices and realized there was no way we could do this," said Kobluk (Youngs, 409). They had to hustle him into a limousine and send him back to the hotel.

Expo '74 also had a separate Folklife Festival, which encompassed folk music, dance, and crafts from the Northwest and from a huge variety of ethnic groups. At various times on the Expo '74 grounds, visitors could hear bagpipes skirling, watch a demonstration of Basque sheepherding, and witness a Gypsy wedding. Calvin Trillin (b. 1935) writing for The New Yorker, called the Folklife Festival "either the best thing at the fair, or a way of making fun of everything else, depending on your mood" (Trillin). He called it "informal instead of rigid," and said that it "emphasized participation -- helping to build a boat or learning how to rope a calf or jousting on logs" (Trillin).

An American Indian exhibit, called Native American's Earth, adjoined the Folklife Festival and provided a look at an entirely different kind of folklife, intrinsic to this particular spot on Earth. The Spokane Indians, who had fished for salmon for millennia below the Spokane Falls, were among the organizers and main participants, along with several other Northwest tribes. They also invited more far-flung tribes, including the Apaches and the Mexican Aztecs, for week-long visits. The tribes staged dances, in which they encouraged white onlookers to join in -- including, most memorably, Russian gymnast Olga Korbut (b. 1955), who was at the fair to perform an exhibition). Native American's Earth proved to be one of fair's most popular attractions.

Expo's Environment, Exxon's Environmentalism

The most powerful attraction of all wasn't a pavilion or an exhibit -- it was the mighty Spokane Falls. Visitors could feel the spray from several footbridges and from the Gondola ride, as well as from the many walkways along the riverbanks. One Chicago visitor said he would remember two things about Expo '74, the "wonderful fresh air" and the "wonderful turbulent river that cut right through the grounds" (Youngs, 396). He said he sometimes sat "for an hour or so, just watching the water pour through there" (Youngs, 396). This was fitting since the falls were, in essence, the root cause of the fair. It was also fitting, for a fair dedicated to the environment, that the iconic symbol was something nature-made, not man-made.

The media reviews were largely positive and many of them noted this fact. Sunset magazine wrote that "Expo's biggest show is its site, the crashing falls, the sound of water, the river overlooks" (Youngs, 498). The mixed, or negative, reviews often cited the inherent hypocrisy in having a preachy save-the-earth theme, even from the likes of General Electric, General Motors, Ford, and the government of the Soviet Union. Trillin wrote, "From whom do we acquire our information about how shrimp get along with oil rigs? From the Sierra Club? ... . No, from Exxon" (Trillin). Meanwhile, the meatier Expo '74 environmental programs, a series of environmental panels, and symposia, were sparsely attended. Those who did attend were not typically fairgoers, but earnest environmentalists preaching to a tiny choir.

Nobody satirized Expo '74's environmental pretensions more thoroughly than the Yippies, the radical and mischievous Youth International Party founded by Abbie Hoffman (1936-1989). Two local Yippies organized a summer hippie encampment in a riverside park they named People's Park. Dozens of Yippies and other activists from around the country arrived at the camp throughout the summer. They held marijuana smoke-ins, and embarked on occasional protest forays into Expo '74 itself. They shouted slogans such as "Environmental World's Farce," and "Expo is Polluting the Area" (Youngs, 447). Once, somebody set fire to an Expo banner, causing police to arrest a dozen protesters, although the charges were later dropped.

Trillin also touched upon another weakness of Expo's environmental theme: The tedious nature of constant nagging and constant earnestness. He wondered whether the Soviets, with their pavilion, were "engaged in a plot to bore the world into submission" (Trillin). However, Expo's environmental mission was certainly not entirely unsuccessful. One visitor, reminiscing 40 years later, said, "This theme really sunk into me as a boy ... . To this day, I would never even consider littering" ("Hello World").

A Great Big Paid-Off Party

The vote of the populace -- in the form of ticket sales -- was positive from the beginning. Attendance hit the one million mark on June 8, nine days before projections. Attendance remained strong throughout the summer, averaging about 35,000 per day. The crowds dropped off after school began in the fall, but then picked up toward the November closing date, as people realized that time was running out. The fair's fourth largest crowd arrived on November 2, and the second largest crowd arrived for closing day, November 3. Attendance was 62,438 on that day. The final tally: 5,187,826 visitors, nearly identical to the organizers' optimistic projections. Compared to attendance at other world's fairs, it was near the low end, and only about half of what Seattle had attracted in 1962. However, it was a clear success for off-the-beaten-track Spokane.

The financial situation looked rockier, at least at first. A few months after the fair's close, the Expo '74 Corporation announced it had a $723,961 deficit. However, the deficit was soon paid off by calling in the pledges made by local donors back in 1970. Many of those same donors came out financially ahead, because of the interest they made on their Expo bonds. Also, the hated B&O tax, which made the fair possible, was removed in 1975, three months ahead of schedule. Tax revenues had been higher than projected, due to increased business generated by the World's Fair. A story in The Spokesman-Review on closing day was headlined, "Local Businessmen Bask in Cash Glow of Expo Days" (Ream).

Mayor Rodgers's pithy quote -- "reduced to its essentials, we gave a great big party and the rest of the world came and paid the bill" -- wasn't entirely accurate, since taxpayers had footed plenty of the bill (Youngs, 503). Yet the world did in fact help Spokane pay for what it could never have afforded on its own, the permanent transformation of Spokane's downtown riverfront.

The Coming of Riverfront Park

As soon as Expo '74 was dismantled, work began on transforming the site into Riverfront Park. In 1978, a new president, Jimmy Carter (b. 1924), came to Spokane to dedicate Riverfront Park, which subsequently become the center of many of Spokane's biggest celebrations, including its Fourth of July and New Year's Eve festivities, as well as its big annual sports festivals, Bloomsday and Hoopfest.

Meanwhile, the Washington Pavilion was sold by the state to Spokane for one dollar, and became the Spokane Opera House and Convention Center. Spokane's downtown was given new energy and it remained stronger commercially than the downtowns of many similar-sized cities. Today, shoppers, tourists and downtown office workers stroll unimpeded to the river and the falls. Rodgers wrote in 2006 that the park complex "changed the entire character of the downtown," and continues to do so today (Rodgers). In others words, Expo '74 accomplished precisely what it was intended to accomplish.

Forty years later, evidence of Expo '74 is easy to find. The clocktower and the tilted dome of the U.S. Pavilion (minus the vinyl covering) still dominate the park's skyline. Kids exploring the park can stumble upon the old outdoor Boeing Amphitheater. The Bavarian Beer Garden building now houses the historic Looff Carrousel.

Beyond it all rumbles the reason for Expo '74's existence: the majestic Spokane Falls. From the safety of the Gondola ride, Riverfront Park visitors can still experience the roar and the spray.