For more than 50 years, a community center named for Harlem Renaissance luminary Langston Hughes (1902-1967) and housed under the dome of a former synagogue has played a role in the artistic, cultural, and social life of Seattle's Central Area. Known since 2013 as the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute, the building located at 104 17th Avenue S at Yesler Way began life as Chevra Bikur Cholim, an orthodox Jewish synagogue. Since 1971, after the City of Seattle used federal Model Cities funds to acquire the building, it has been known variously as the Yesler-Atlantic Community Center, the Langston Hughes Cultural Center, the Langston Hughes Cultural Arts Center, the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Center, and the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute. Management and administrative structures for center operations have changed many times, but Seattle residents' fondness for Langston Hughes and the creative atmosphere he inspired has endured. Many Seattleites with personal, cultural, and professional ties to the Central Area refer affectionately to the building as "Langston."

Chevra Bikur Cholim

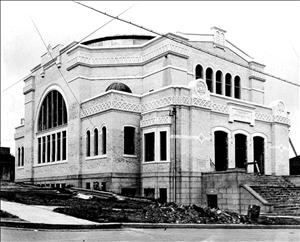

Chevra Bikur Cholim was established in 1891 and the congregation built a synagogue at 13th Avenue and Washington Street in 1897. In 1908, it began raising funds for a new building to accommodate its growing membership. Designed by B. Marcus Priteca (1889-1971) and completed in 1915, the new synagogue could seat up to 1,400 in a white brick terra cotta structure topped by a dome rising 70 feet above street level. Decades later, the congregation sold the building to the City of Seattle in 1969 as the result of efforts by Walter R. Hundley (1929-2002), program director of Seattle's Model Cities Program, and other Central Area citizens to acquire it for use as a community center. Some services and events continued to be held in the synagogue through 1971. That year Chevra Bikur Cholim merged with Congregation Machzikay Hadath, becoming Congregation Bikur Cholim. That congregation's new building on S Morgan Street was completed in 1972.

Yesler-Atlantic Community Center

Seattle was the first city awarded federal funds to implement urban renewal under the Model Cities Program (established by the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Act of 1966). The program was intended to address poverty and social inequalities by improving physical and social conditions. Citizen involvement in planning and development was a major element of the program. In 1967, Hundley, then director of the Central Area Motivation Program, was selected by a citizen's committee to head Seattle's Model Cities Program, and the effort he and others led to purchase the synagogue was conducted under the auspices of that program. Once the purchase had been arranged, planning began for use of the building as a community center managed by the city parks and recreation department. A large, multipurpose facility in the Central Area had the potential to develop stronger community ties while dollars circulated close to home. According to one analysis, "instead of groups having to go out of their area for a special convention or event, they would now have a special facility in which to hold their own meetings or events, including a large banquet facility and a large hall for their presentations" (Gabrielson, 1972). Seattle's Model Cities office estimated that nearby residents would make up 90 percent of those who used the center.

A 1972 agreement called for a range of city-sponsored programs and activities -- including classes in English for immigrants, flower arranging, dance, crafts, Japanese cooking, African history, and Filipino art; social club events; a food program; and youth social activities -- to move from the Collins Recreation Center at 16th and Washington to the Yesler Neighborhood Center Project, as the former synagogue building was to be known. The proposed classes were to be free to the public and funded by grants. The agreement also mentioned "provision of space for day care programming, use of the facility by the Cinematography Project of the Model Cities Program, and provision of Drop-In Center activities for the elderly of the service area" (Gabrielson, 1972).

Construction to convert the synagogue into a community center began on April 6, 1971, and was completed on March 31, 1972. Daycare and office space occupied an extension built by Chevra Bikur Cholim as its Education Annex in 1961-1962. A house on the southwest corner of the lot, formerly occupied by synagogue caretakers, was demolished and a patio/play area for the childcare center built in its place. The final cost of the renovated facility was $761,968.23. On July 16, 1972, the newly renovated Yesler-Atlantic Community Center was dedicated in a public ceremony.

Community Engagement

The new center's small staff devoted itself to creating a welcoming atmosphere. Performing artists, churches, and community groups rented the center's theater for a variety of events. Supervisor Willie Campbell's list of some of those who used the building in 1973 provides a snapshot of Central Area life at the time. It includes various school department groups, Model Cities staff, the Human Rights and Community Development departments, and other city agencies; many religious groups, including New Hope Baptist Church, Cherry Hill Baptist Church, Jehovah's Witnesses, Clear Tone Gospel Church, and Damascus Baptist Church; organizations including the King County Foster Parents Association, Washington State Women's Political Caucus, Century Social Club, Seattle Council PTA, Seattle United Black Arts Guild, Harborview Community Health Center, Black Culture Workshop, Seattle Chapter of the Links, Inc., and Jack & Jill Organization of America; a Koyasan Folk Lore Open House; the Safeway Christmas Party; and many other shows, meetings, wedding showers, graduations, and more.

Despite this promising start, an exchange of letters in early 1973 indicates that some classes suffered from low participation rates. In a January 1973 memorandum Turner and Campbell expressed concerns about the center's future. Staff promoted classes and events by sending weekly news releases to radio stations KJR, KYAC, and KIXI. They also sent releases to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, The Facts, and The Seattle Medium newspapers, as well as the Franklin High School student newsletter. In April 1973, Model Cities Program Director Hundley warned parks superintendent Hans A. Thompson that Model Cities would not be able to continue paying for a security guard at the center. In October 1974 the center received an additional $28,500 in Model Cities funds to extend operation support. It soon began charging a $5 class-enrollment fee.

New Name for Changing Times

The global Black Consciousness movement of the 1960s and 1970s led to discussion of a new name for the center that would be representative of the history and culture of the neighborhood's primarily African American population. Names considered by the Yesler-Atlantic Community Center Board included the DuBois Dome (proposed by Mildred Russell on January 9, 1973, after W. E. B. DuBois); the Paul Robeson Cultural Center (proposed by Russell on February 24, 1973); and the Langston Hughes Cultural Center, recommended by Ms. J. T. Stewart, the Chair of the Yesler-Atlantic Advisory Board. Bruce Chapman, chairman of the city council's Parks and Public Ground Committee, supported naming the center for Hughes: "I understand that an excellent name has been suggested for the Yesler-Atlantic Community Center. In my opinion, to call it the 'Langston Hughes Cultural Center' would most appropriately honor a great Black American poet and writer. The name is fitting and I do support it" (Chapman letter, April 3, 1973).

The name change was confirmed on May 30, 1973, and subsequently placed on record and officially adopted by the City of Seattle. The Seattle Times announced a June 9, 1974, ceremony, luncheon, and entertainment for the dedication of the center under its new name: the Langston Hughes Cultural Arts Center (LHCAC).

Langston Hughes in Seattle

Poet, playwright, author, traveler, and Harlem Renaissance luminary Langston Hughes, the center's future namesake, first spoke in Seattle on Thursday, May 26, 1932. Three years later he was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship. Hughes delivered a public lecture titled "Color Around the World" on January 24, 1946, one of a series presented by the Associated Women Students of the University of Washington. A headline published the following day read "Negroes Happiest in Seattle, Says Writer of Verse, Song," but Hughes's actual commentary was not quite so idealistic:

"Hughes ... reported today the impression prevails in the rest of the nation that Seattle is 'a liberal city where social problems do not exist on the same scale as elsewhere.' Hughes ... said that Seattle had more to offer a non-white in educational and cultural lines than many other western and eastern cities. 'However, the great influx of Negroes to the West was purely economic,' he added. 'Now that they are here, they are finding it a much happier place in which to live than say, the South, or Portland, Or. ... Negroes all over America are under the impression that Seattle understands them, although there is not too much opportunity for them here'" ("Negroes Happiest ...").

Hughes's Harlem-set musical comedy Simply Heavenly was staged by The Contemporary Players at Seattle University's Piggott Auditorium in 1959 and again in 1960 at the Boards Playhouse. In 1967, Paul Bellesen established North by Northwest Adventurers, a Central Area-based youth seafaring program, and began raising funds to purchase a boat to be christened the Langston Hughes. Years earlier, Hughes had sent Bellesen an autographed copy of his book The Best of Simple. The organization was able to purchase an 85-foot tugboat built in Canada in 1906; two other boats were later donated. Students took to the waters of Puget Sound and learned helmsmanship, charting, communication, marlin-spike seamanship, deck duties, scuba diving, safety, ocean studies, and more. Works by Hughes shared space with nautical books on the shipboard library shelves. In the early 2000s, Jacqueline Moscou, artistic director of the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Center, directed annual productions of Hughes' play Black Nativity, staged at Intiman, the Moore, and other Seattle theaters.

Classes, Food, and Clothing

In 1974 the Langston Hughes Cultural Arts Center offered classes for a wide audience: pantomime for the deaf, advanced Karate, Koyasan folklore, international crafts for ages 6-12 and adults (macramé, batik, tie dye, clay stitchery and block printing), Ikebana flower arranging, puppetry, acting, public speaking, music, art, literature, stage lighting, and more. Many children from the nearby St. Mary's Elementary School attended classes twice a week after school. Francene Major, hired as program director in 1974, told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, "We plan to add creative writing, drama, modeling classes, and a course to teach the kids to take care of their Afro haircuts ... I hope to add other programs as soon as I find out what the community would like. That's always hard to judge but we have to find out their needs if we are going to serve them" (Grimley).

The center offered more than arts and culture. The Post-Intelligencer reported in 1974: "A big draw to the center is a food program through the Department of Agriculture. Free meals are served to any young person up to 21 years. During the school year breakfast is served on Saturdays and dinner is at 5 p.m. Mondays through Fridays. Snacks also are provided to children after classes. Last month 298 breakfasts, 2,285 dinners and 1,784 snacks were served" (Grimley).

Food and clothing were distributed to needy adults at the December 1973 holiday party. This practice of generosity continued for years. LHCAC addressed the problem of child hunger by becoming a location for the city-sponsored Summer Sack Lunch Program. During the 1980s, Central Area United Senior Citizens used the center's multipurpose room for its lunch program. By 1976 Hundley had been appointed budget director at the Seattle Parks Department. He remained supportive of LHCAC, as shown by his advocacy for the center's Food Supplement Program. When federal Department of Agriculture funding failed to keep up with increased food prices, Hundley requested an emergency funds appropriation and the parks department transferred $1,500 between budget areas, keeping the Food Supplement Program operating.

Community Engagement

LHCAC remained busy through the end of the 1970s. A 1978 program schedule mentions the Langston Hughes Repertory Theatre Company: "this community oriented center has formed the first in-house community theatre in the Central Area" ("Langston Hughes ... Winter 1978"). The company staged Jean Genet's The Blacks in 1979.

During 1978 and 1979 the center offered courses in karate, astronomy, tumbling, meditation, yoga, photography, painting, drawing, and playwriting in addition to "Senior Citizen Activities" and an occasional on-site, drop-in Geriatric Clinic. "Survival for Parents" provided "an opportunity to talk about concerns and problems facing parents today. Single parents and extended families are welcome" ("Langston Hughes ... Winter 1978"). Instructors taught classes ranging from woodworking to playing bridge and chess to drill-team steps, patterns, and technique to Chinese brush painting and calligraphy. Children aged 8 to 16 could get help from tutors or learn to cook nutritious meals with the King County and Washington State University Extension service. The disco craze was mirrored in a six-week Disco Dance Lessons course by Larry Cabrales: "Keep up with the modern dance steps. Learn such steps as the Bump and the Hustle from a professional teacher" ("Langston Hughes ... Winter 1979"). A roller-skating class was held at nearby Washington Middle School. A twice-weekly drop-in activity group for young mothers provided activities (macramé, sewing, drama, writing, art) and a chance to make friends. Robert Long taught American Sign Language. Seattle and King County libraries provided films for an ongoing free children's film series. Daily drop-in activities for children 16 and under included a social hour with ping-pong, pool, and other games. LHCAC classes now cost $5-$10; a HUD Block Grant provided compensation for instructors.

During the early 1980s LHCAC offered fewer classes than it had in the prior decade. However, certain artists and program instructors became associated with the center as a result of frequent classes and performances there, in effect becomng artists-in-residence and enabling intensive concentrations in their respective disciplines. The Paul Robeson Community Theater Group became LHCAC's theater-in-residence around 1980. It presented several plays written or adapted by actor, director, producer, and longtime Central Area resident Umeme Upesi. In 1982 Seattle's chapter of the National Council of Negro Women rented the center to present the traveling film series Reel to Real: Black Women Make Films. The event foreshadowed the Langston Hughes African American Film Festival, established by artistic director Jacqueline Moscou in 2003.

Arts and Culture of the African Diaspora

LHCAC programming upheld the center's commitment to providing access to arts and culture from across the African diaspora and supporting the effort with rehearsal and performance space. From the time of its opening the center was a frequent location for performances by African drumming and dance ensembles, some led by professional musicians and dancers, other based at local high schools and middle schools. In March 1974, Capoeira Angola Western Washington State presented "The Capoeira Exhibition," an event described as "a program on African culture featuring a ballet of gladiators involved in a mock battle" ("African Ballet ..."). By 1982 LHCAC offered Capoeira classes. In 1984 Jack Spencer taught steel drums. In 1985, Won-Ldy Paye taught Liberian folk dance, Liberian ballet dance (dance-drama), and Liberian drama and poetry. During the 1980s, Kofi Anang led a drumming and dance ensemble that frequently rehearsed at LHCAC and taught Ghanaian dance. In the winter of 1980 Zimbabwean dancer and musician Lora Chiorah-Dye began teaching Shona dance, music, singing, and language classes. From 1979 Sheree Sparks taught mbira (similar to the kalimba, or 'thumb piano'), Southern African drumming, and African children's games and songs. In 1982 Sparks joined the Shona language classes as co-teacher; Sparks would later teach marimba classes and lead Sukutai Marimba Ensemble rehearsals in the first-floor classrooms through the mid-2000s. Christina Pullen also taught African drumming and dance in addition to teaching acting, writing and producing her play Under the Auspices, and directing the Senior Citizens Acting Ensemble.

Karate classes drew loyal students to LHCAC for years; for a few seasons the center offered "Karate for Women Only." In April 1982 the Seattle Central Community College Asian Pacific Student Organization and the Asian Pacific American Arts Consortium presented the multimedia play Breaking Out, in the LHCAC theater. Playwright Timoteo Cordova staged the world premiere of his play Heart of the Son, about political leader and Philippine President General Emilio Aguinaldo, at LHCAC in 1994.

A Full House

In 1987, Seattle Parks and Recreation planner Lou Ann Kirby compiled an issue paper that included results of a detailed study of LHCAC as one of three specific sites under consideration as an African American Cultural Heritage Center in the Central Area. She wrote: "As the only cultural arts center remaining under the Department's jurisdiction, Langston Hughes offers a unique program. Its target service area is citywide, and because of its outstanding ethnic cultural tradition, it has regional appeal" (Kirby, 8). However, the study noted that the LHCAC building needed extensive renovation and pointed out that unlike other Seattle community centers, "Langston Hughes lacks a gymnasium and therefore is extremely limited in its ability to offer athletic programs. ... Langston Hughes is limited to three or four activities at a time" (Kirby, 13). Despite these concerns the report recognized that "the size and acoustical qualities of the theater constitute an important community asset. During the school year, the theater is generally scheduled to capacity ... Theater revenues average about $3,000 a year, which places Langston Hughes near the top for revenue production among the Department's 25 community centers" (Kirby, 13).

In fact, demand for the theater was so great that Parks Superintendent Hundley noted in a July 1987 memo that the resident Paul Robeson Theater Company had been using moveable set pieces, rather than larger and more detailed sets that would have to be left in place, for its theatrical productions so that the theater could also be used for weekday classes and rentals. An attachment to Hundley's memo lists an even greater array of events at the theater than in 1973, including meetings of the Mayor's KidsPlace Task Force, King County Arts Commission, Seattle Police Department Crime Prevention, and Central Area Chamber of Commerce; benefit shows for University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff Alumni Benefit Show, Gay Theatre of Seattle, and Amazing Manning Brothers Church; city Human Rights Department public hearings; performances including 10 Black History Month performances, a Chicano Theater production of "Chicana," Black Community Festival Lip Sync Show, Musavir Middle Eastern Dancers, Girls' Club Variety Show, Native American Action Committee Cultural Evening, and Suzuki Violin School Recital; Paul Robeson Theater classes and rehearsals; First Church of Christ Scientist lectures; Gemini International gospel films; a School Board Candidates Forum; a National Conference of Black Lawyers Community Forum, and more.

Langston Hughes Center and Seattle Hip-Hop

By the summer of 1984 LHCAC was offering 10- to 18-year-olds classes in "Break Dancing -- New! Exciting! Breathtaking! The current craze that is sweeping the nation" (LHCAC Summer Program Schedule, 1984). In addition, LHCAC was a popular performance space for rappers and dancers. Anthony Ray (b. 1963) -- better known as Seattle rap star Sir Mix-a-Lot -- lived at neighboring Bryant Manor, 1801 East Yesler Way, for some years during his childhood. B-Self (Bill Rider), half of hip-hop duo Ghetto Chilldren, told Seattle Times reporter Vanessa Ho in 1994: "People think that a hip-hop show is going to be violent ... but you can go to the Langston Hughes (Cultural Arts Center) and see some quality hip hop and there won't be any violence" ("Ghetto Chilldren ..."). Some productions during the 1990s and 2000s combined theater and hip-hop in musical plays such as Pressure: A Hip Hop Theater Experience (1995).

Back to its Roots was a three-day hip-hop arts festival first organized in 2003 by Moscou. Talib Kweli opened the 2006 festival, introducing local performers including Madeleine Clifford and Hollis Wong-Wear, performing as the rap duo Canary Sings. Hip-hop performers at this festival and other LHCAC events included Source of Labor; Esai, a Samoan-American spoken-word artist; a production of playwright Melissa Noelle Green's Hip Hop: Back to its Roots; hip-hop duo the Silent Lamb Project; Seattle's Finest, a group combining gymnastics, break dancing, hip-hop dancing, and tap; and DJ Spinderella of Salt-n-Pepa, among many other Pacific Northwest hip-hop performers.

Social Issues Addressed

LHCAC was frequently the site of creative exploration or discussion of local and international subjects of political, social, and community concern. South African anti-apartheid leaders Rabbi Ben Isaacson of Johannesburg and Rev. Zachariah Mokgoebo, a black minister from Soweto, spoke at LHCAC in March 1987.

Rising crime rates produced creative responses. 1989 saw the Madrona Youth Theatre's presentation of Peer Pressure, an anti-drug, anti-gang play by local playwright James Lollie with original music composed by Reco Bembry. Steve Sneed directed the cast of teenagers and young adults; he later led LHCAC as Recreation Coordinator and then director of the center until 2000. Lollie also wrote the screenplay for the 1995 film anti-youth-violence project What Could Have Been. LHCAC was a sponsor of the film and provided rehearsal space. Film and TV director John Gordon-Hill directed the film, donating his time and expertise. Many of the teen actors came from Central Area communities near LHCAC. Felicia Loud, later a renowned vocalist (Black Stax) and actor, was among the cast members.

A Place for New and Experienced Artists

Teenagers and young adults learned performance skills through their participation in LHCAC programs. The Seattle Times reported in 1989 on one such program: "The Madrona Youth Theater's summer program has a long string of successes, including Little Miss Dreamer, based on the life of blues singer Bessie Smith; Boys Will B-Boys, by A. M. Collins, who wrote Angry Housewives; Slow Dance on the Killing Ground, with guest artist John Gilbert; and last year's West Coast premiere of Sing on, Ms. Griot ... Early productions were staged in the Madrona Community Center ... The Langston Hughes Cultural Center now seems to be its permanent home" (Duncan).

The All-Teen Summer Musical remained one of LHCAC's most popular programs. Participating youth guided by theater professionals learned aspects of musical theater and technical production. The first Summer Musical production was Summer Rhapsody Reunion, staged in 1996; subsequent productions included Peter Pan, The Wiz, and Grease. During the rest of the year, young people in Central and South Seattle participated in such events as the Best of the Best talent shows of the 1990s and early 2000s.

Performing arts luminaries from a broad range of disciplines treaded the boards of Langston Hughes: musician and activist Gil Scott-Heron; Arthur Duncan, a tap dancer featured on the Lawrence Welk television show for 17 years; actor and film producer Danny Glover (as a guest of the Langston Hughes African American Film Festival); Ghanaian drum and dance ensemble Ocheami, led by Kofi Anang and Cecilia Anang; the Kronos String Quartet; Marvin Tunney of the Alvin Ailey Dance Company; Edna Daigre's Ewajo Dance Workshop; the Joe Brazil Orchestra; the San Francisco Mime Troupe; Harlem tap dancer Jeni LeGon; African-dance teacher and performer Makeda; the Choreopoets, an ensemble performing the song, dance, and poetry repertoire of African American artists; Sounds of the Northwest, an a capella choir performing traditional African American music; the Inception Dance Company; and hundreds of other touring and local performers.

Acclaimed artist Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000), a recipient of the NAACP's Spingarn Medal in addition to countless arts awards, exhibited paintings at LHCAC in 1978 during a Black History Month event. The 2004 Black to the Future black science fiction festival produced by the Central District Forum for Arts and Ideas used LHCAC as its screening location. Black to the Future festival guests included science fiction and speculative fiction authors Charles Johnson, Nalo Hopkinson, Octavia Butler, Steven Barnes, Tananarive Due, Walter Mosley, and Nisi Shawl. Science fiction films were shown free to Central Area fans 26 years earlier during the summer "Star-Worlds Film Festival" series.

A Time of Transition

After the implementation of a parks department reorganization plan in 2001, the center was renamed the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Center (LHPAC). Executive Director Royal Alley-Barnes led a two-year renovation of the building between 2010 and 2012. The center experienced another substantive change in 2013, when its management was transferred to the City of Seattle Office of Arts & Culture. Along with the change of management came a new name: the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute (LHPAI).

Following the renovation, community arts continued to thrive below the former synagogue's soaring dome. The annual Langston Hughes African American Film Festival showed an international lineup of films every spring. Although LHPAI had no resident theater company in 2014, Artistic Director Moscou presented innovative theatrical productions such as the first production of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman with an all-Black cast (2005), and the 2013 world premiere of Hello Darlins: Moms' Got Something to Tell You, Seattle playwright Dan Owens's play about comedienne Jackie "Moms" Mabley. The renovated center launched an artist-in-residence program in 2012 and again offered arts classes, an annual fundraising gala, the Teen Summer Musical, and music and theater.

In 2016, Langston became a non-profit organization purposed with "cultivating Black brilliance" (Langston website). To help with the transition, Seattle's Office of Arts & Culture hired a consultant to work with a community-based transition team, and committed to provide financial, operational, and maintenance support through 2018. "By June 2015, it had become clear that three years was not enough time for Langston Hughes to become self-sustaining and the transition timeline would have to be extended. The nonprofit would take over the programming as planned in January 2016, but city support would continue for at least seven and possibly up to 10 years" (Tate). Alley-Barnes retired in December 2015. "My tenure here is complete," she said. "I've done due diligence. This organization is set to be robust. It has a long history, there are amazing people here, there's a huge community legacy" (Tate). As of 2022, according to Langston's website, the Office of Arts & Culture remains "our close partner and major sponsor to this day" ("About Us").