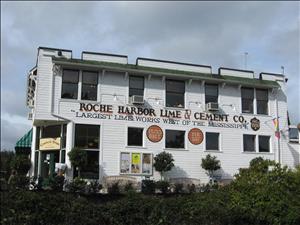

Limestone quarrying and lime processing began at Roche Harbor, located on the north end of San Juan Island in San Juan County, in the early 1880s. Under the leadership of John S. McMillin (1855-1936), the Tacoma & Roche Harbor Lime Company, incorporated in 1886, expanded to become the largest lime operation in Washington, and the company town of Roche Harbor grew to some 250 people. Roche Harbor continued to dominate the market until the 1930s, when the demand for lime gradually fell away and companies on the mainland, with newer technology and cheaper transportation costs, competed for a larger market share. Sold in 1956, the town and its lime processing works were converted into a tourist destination.

Origins

The origins of lime operations at Roche Harbor are shrouded in a fog of uncertainty. In 1860, when Britain and the U.S. were jointly occupying the island during the Pig War boundary dispute, British troops under the command of Captain Bazalgette of the Royal Marines operated a lime kiln, probably in the vicinity of English Camp on Garrison Bay, some three miles south of Roche Harbor. Rumors abound that the British developed the kilns at Roche Harbor itself, but there is little evidence for this. An American named S. Meyerbach, through the agency of William Brannock, attempted to establish a kiln in the vicinity of the British at Roche Harbor, but he was dissuaded by the American forces because it lay within the purview of the British authority.

Sometime after the 1872 settlement of the boundary dispute made American land laws applicable, Joseph Rueff filed a claim for the land encompassing Roche Harbor, receiving his patent April 1877. In the next two years, the property changed hands several times. Israel Katz bought the land from Rueff in 1878; a year later he sold it to Robert and Richard Scurr, who had come to San Juan in 1871 and 1873 respectively. The Scurrs, in conjunction with the Canadian brothers Alexander, Colin, and Donald Ross, constructed two kilns as well as a log boarding house for workers.

John Stafford McMillin

It was John Stafford McMillin who built Roche Harbor into the largest lime works on the West Coast. McMillin grew up in Indiana and moved to Tacoma in 1882. There he became involved in the lime industry in the Puyallup Valley, incorporating the Tacoma Lime Company in 1883. McMillin bought the Roche Harbor property and works from the Scurr and Ross brothers in 1886, established the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Company, and initiated a program of improvements to the production process and physical plant.

The West Shore, a regional magazine that described the new works in 1889, noted that "When the new company took possession of the works, two years ago, there were but two kilns, of the large stone pattern, which were turning out about eight thousand barrels a year, a small lime shed, a manager's residence, three or four small buildings, and three log cabins for men" (The West Shore, 411). McMillin expanded the wharfs, loading platforms, and quarries, and constructed a new cooperage, office, and warehouses. He also increased production by constructing three new kilns: one of the older stone variety and two of a newer "Monitor" design, with boiler steel encasing the brick lining. By 1891, he had more than doubled capacity by building Kiln Battery No. 2, a complex of eight Monitor kilns, bringing the total to 13 kilns. Production rose from the Scurr-period output of 8,000 barrels annually in the mid-1880s to almost 150,000 by the 1890s.

Making Lime

The limestone quarrying and lime-making process worked largely through gravity. Sections of rock were blasted from the vertical faces of limestone deposits upslope of the kilns and the resulting boulders were blown up and broken into smaller pieces for loading into the kilns. A 9- or 12-pound rock hammer with a narrow bit was used to break medium-sized rocks into useable chunks, usually 8-12 inches in diameter, care being taken to waste as little rock as possible in small chips. This size of rock allowed the hot gases to pass around the rocks piled in the kilns in order to heat them thoroughly. Temporary, 36-inch-gauge tracks were laid from more permanent rail lines and trestles to the quarry currently being worked on. The rocks were then loaded by hand into rail or trestle cars (and later trucks) and moved by manpower, mule, or later 0-4-0 saddle-tank locomotive to either stockpiles for shipping, unprocessed, or bins for burning in kilns to produce lime.

Lime is produced through calcination or "burning." Limestone is subjected to a great heat -- 1,650 to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit -- in order to drive off carbon dioxide, leaving pure lime. This process occurs in kilns: vertical shafts full of limestone with heat added through fireboxes on the sides. The early kilns (Numbers 3 and 4) at Roche Harbor were constructed of an inner lining of firebrick surrounded by stone and secured through a framework of heavy wooden beams, with a log-cribbing hopper on top to contain the raw limestone. The three adjacent kilns (1, 2 and 5) and eight in Kiln Battery No. 2 (6-13) consisted of firebrick-lined shafts encased in sheet (or "boiler") metal. At the top, there was a tall chimney-like stack that was lined with a single layer of firebrick. In between, a short section tapered out to the heating shaft; on the hill-side of this taper was a hinged charging door, which allowed for loading the stone from the bins via chutes into the heating chamber. In both types of kiln, the limestone was loaded into the top of the heating chamber and the finished rock removed from the bottom every four hours.

The "burnt" rock, which was still in large chunks (6-8 inches in diameter), was raked out of the bottom part of the kilns by means of long (10-20 foot) rods and channeled into a chute. From there it would be packed in barrels, whose heads were sealed in order to keep the lime from hydrating once again. The barrels were placed on scales at the base of each kiln and filled with exactly 200 pounds of lime, to ensure a uniform product. In a large structure at Kiln Battery No. 2, the coopers (barrel-makers), on a floor above, sent the barrels to the packing area at the base of the kilns via ramps, where the removal of one barrel caused the next to roll down into its place.

In the 1890s McMillin introduced a new type of barrel. The "staveless barrel" was based on a method developed by the Waterman-Chapman Barrel Machine Company, whereby machines shaved a thick veneer for the two halves of a barrel, resulting in just two staves and joints, as opposed to a regular barrel of 17 staves and joints. McMillin purchased rights to the process in 1891, and a large plant for production of these new barrels was constructed on the eastern shore of the harbor. After being loaded with lime, barrels were lifted onto flatbed wagons on tracks, which were drawn by horses to warehouses near the wharf, where the barrels could be stored until shipped to market. Workers took great pride in being able to stack the heavy barrels three layers high.

Transporting Lime

Roche Harbor had a fleet of ships called Roche Harbor Lime Transport that plied significant West Coast trade routes such as the three-to-five-day run from Puget Sound to San Francisco or the Vancouver- or Victoria-to-Portland run. These included The Star of Chile, a large white-hulled three-master; the William G. Irwin, a 550-ton brigantine; the Archer, an iron-hulled barkentine; and a 60-ton steam tug, the Roche Harbor. Ships laden with barrels of lime, some stacked on open decks, were carrying a very dangerous cargo because quicklime that becomes wet is highly combustible. The William G. Irwin, loaded with a cargo of lime worth $30,000, was scuttled in San Francisco Bay after a month's efforts to quell a smoldering pile, and even the Archer, with its iron hull, burned and sank with a full load of lime.

Despite the risks of transporting it, the demand for lime was large and growing. It had been used for years as the primary mortar for masonry (brick or stone) buildings, and could also be used as a plaster covering for walls and other surfaces. During the 1880s, the population of the Northwest swelled by a phenomenal 165 percent, primarily in four urban areas: Portland, Seattle, Spokane, and Tacoma. Seattle's population jumped from 3,553 to nearly 43,000 between 1880 and 1889. By 1910, one-third of the entire population of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho lived in these four cities. Devastating fires in Ellensburg, Seattle, and Spokane in 1889 brought about changes in attitude about safety, resulting in new construction techniques. Buildings constructed of brick with lime mortar were erected in place of the wood structures easily consumed by fire. This generated enormous demand for lime as mortar in the Pacific Northwest and the entire West Coast. Around the same time, use of Portland cement, of which lime is a key ingredient, in construction was increasing. Although cement has ancient origins, the late 1890s and early 1900s saw its growing use in conjunction with reinforced steel rods.

In addition to use in construction, lime and limestone are also used as a flux in metallurgy and in the production of paper (in pulp mills). Quicklime was used as a flux in smelting steel and other metals to remove impurities such as phosphorous, sulfur, and silica, and to a lesser extent, manganese. Major metal refineries in the region included smelters in Everett and Tacoma; both operations eventually became part of the American Refining and Smelting Corporation (ASARCO). "Paper Rock" was used for processing the pulp (cellulose) in the papermaking process.

After the higher grade of limestone had been quarried in San Juan County, the remaining rock was quarried for pulp mills in Everett (Everett Lime Company and the Soundview Company) and Seattle (Washington Pulp and Paper Company and Crown Zellerbach). Sugar plantations used Roche Harbor lime as "sugar rock" in the refining process. Lime was also used as a source of fertilizer in sugar-cane fields. Ships bearing barrels of lime for the sugar plantations sailed from Roche Harbor to Hawaii on a regular basis.

Company Town

Laborers at Roche Harbor were from many countries; notable among them was a large contingent of Japanese. After the U.S. Chinese Exclusion Act and the Japanese Meiji Restoration Act (both 1882), young Japanese men were attracted to labor in the industrial mining areas of the Pacific Northwest. Roche Harbor had as many as 24 at one time. They sent away to Japan for "picture brides," and both single men and families were housed in some 25 or 30 sheds located at the head of the lagoon on the north side of the village; this was referred to as Japan Town. Being familiar with pyrotechnics, they often worked as "powdermen," and as gardeners and domestic staff for the McMillin household. The 1910 federal census reveals a growing number of other ethnic groups, such as Scandinavians and Russians.

In addition to the quarries, lime works, warehouses, and docks, Roche Harbor comprised a small village including residences for McMillin and his family as well as management and workers, a hotel, post office, store, church, school, and doctor's office. The Hotel de Haro was initially used as a boarding house and mess hall. There were also rooming houses -- barracks and log structures -- for single men as well as cottages for married couples. The Roche Harbor Post Office, established by the Scurrs in 1882, lasted until 1964 (in subsequent years a small post office operated at Roche Harbor as a branch of the post office in Friday Harbor, about 10 miles away on the island's east shore).

The company store, run by Shropshire, England, native Thomas R. Kinsey, was originally located at the waterside end of the dock. After a fire in 1923, it was moved to the land side of the rebuilt dock (where it remained as of 2014). Although the store supplied not only Roche Harbor employees but also residents on the north end of San Juan Island, workers were initially paid in scrip that was only redeemable at Roche Harbor; later, workers requested cash. McMillin built a Methodist Church overlooking the harbor and this was used as a school during the weekdays. Another school building was later constructed near the married men's cottages. The company also provided medical services through Dr. Victor Capron (1867-1934), who arrived in 1898, first living in a house upslope from the hotel, and later using the house for his medical practice after he moved to Friday Harbor.

Roche Harbor was often in the forefront of bringing technological innovations to the islands. For instance, in 1902 the local paper reported that "The new dynamo has arrived and the wires are up for the new electric light plant to be installed at the lime kilns to light the works, hotel and all the companie's [sic] operating buildings" (San Juan Islander, August 21,1902). According to Wolf Bauer (1912-2016), who worked there as an engineer in the late 1930s, acquisition of a new diesel generator in the 1930s allowed the operations at Roche Harbor to switch over from machinery driven by flat belts working off a common jackshaft to equipment operated from individual motors. Long before, in the early 1900s, McMillin had attempted to upgrade the whole operation into a cement-production facility with state-of-the-industry equipment, but his efforts were frustrated by a many-year lawsuit brought by Ernest Cowell.

John S. McMillin was an almost stereotypical Robber Baron-style capitalist. He was involved in national political and fraternal organizations, being an ardent Republican, a founding member of Sigma Chi, and a 32nd-degree mason. Stories abound of McMillin insisting that his workers vote Republican, and firing those who didn't. Indeed, the lives of Roche Harbor workers were controlled not only through their jobs, wages, and working conditions, but also through housing and the provision of supplies at the store. McMillin and his family led a fairly lavish lifestyle. They entertained visitors from Seattle and other nearby cities, throwing large banquets at Roche Harbor and on nearby Henry Island. McMillin took his yacht, the Calcite, on cruises through the San Juan Islands and neighboring waters, often together with his friend Robert Butchart (1856-1943), who owned the lime works on Vancouver Island.

Afterglow Vista Mausoleum

The ultimate monument to the McMillin era at Roche Harbor is the McMillin mausoleum. John S. McMillin conceived the mausoleum as a memorial to his family, and particularly his son Fred (1880-1922), whom he had groomed to be his successor in the business. The plan of the mausoleum -- a circular table around which six columns and six chairs containing the remains of the parents and their four children were arranged -- was designed to represent the gathering of the family in the hereafter. A seventh space was reserved for a "missing" chair, and its corresponding column was designed and constructed as "broken" or "incomplete", to represent the unfinished life of man on this earth.

This column was also oriented so that the setting sun would cast a shadow falling between the chairs of the parents, John and Louella. This, along with the intense, lingering sunsets for which Roche Harbor was noted and the yellowish coloration of the columns, accounted for the mausoleum's name: Afterglow Vista. The original design called for a bronze dome topped by a Maltese Cross, representative of Sigma Chi. However, McMillin's surviving son Paul Hiett McMillin (1886-1961), who had taken charge of the company from his father in 1936 -- the year his father began planning the mausoleum -- balked at the additional cost ($20,000) and canceled the order, thereby earning his father's enmity. John S. McMillin died on November 3, 1936, and his ashes were interred in the monument.

Vicissitudes

Roche Harbor suffered a series of vicissitudes during the 1920s and 1930s. On July 28, 1923, a fire swept through the works, destroying the kilns, warehouses, store, and wharf. McMillin responded quickly, and apparently had the kilns operating within a few days. He rebuilt the wharf, with a new store, office, community hall, and yacht club. Production continued through the late 1920s until the onset of the Great Depression, reaching a nadir in 1933. A close look at Roche Harbor's production charts indicates declines around the time of World War I, at the onset of the Depression, and during World War II. (An exception appears to be 1937, which may have coincided with the construction of Grand Coulee Dam, the largest concrete structure in the world.)

By the late 1930s, the processing of lime at Roche Harbor had not changed significantly in almost 50 years; it was inefficient and labor-intensive, and therefore not cost-effective to continue operations. Added to this were the rise in shipping costs and fewer ships plying the waters of Puget Sound. Freight bound for West Coast cities was primarily being sent by rail. There was some market for agricultural lime in Eastern Washington, which meant it was packaged in sacks and hauled by barge or scows from Roche Harbor to Everett, where it could easily be transferred to rail cars.

Paul McMillin, who had first managed the store at Roche Harbor, succeeded his brother Fred as vice president upon the latter's death. In 1936, he assumed the presidency from his father. Paul McMillin was known as a headstrong executive who carried side arms while among his workers. Roche Harbor was one of the last lime operations in the United States to unionize; in 1938, after the company refused to recognize the union, workers went on strike. Paul McMillin responded by appearing before union representatives with a shotgun and ordering the engineers and other management to take over quarrying, burning, and loading operations. The strike lasted for three months; it was settled when customers told the company that they would not purchase scab lime. During the 1940s and early 1950s, production gradually shifted to paper rock, with less lime production.

From Lime Works to Resort

In 1956, Reuben J. Tarte (1901-1968), his wife Clara Diaz Tarte (1899-1990), and their son Neil Tarte (1927-2014) bought Roche Harbor from the McMillins. They developed the facilities into a resort and "boatel." In this process, many of the metal structures of the kilns, as well as the old warehouses, were dismantled. In 1988, Rich Komen and Verne Howard bought the property under the name of Roche Harbor Resorts; in 1997, Howard sold his interest to Saltchuk Resources.

Roche Harbor Resorts has maintained and stabilized the remains of Kilns 3 & 4 and the base of Battery No. 2 (Kilns 6-13), the Hotel de Haro, and the main portion of the office and store, as well as several of the residences and workers' quarters. These structures, along with the mausoleum, offer a monument to what was once the "Largest Lime Works West of the Mississippi," as the Roche Harbor sign proudly proclaims.