On January 10, 1901, water from Seattle's new Cedar River water-supply system reaches city residents for the first time. The completion of the Cedar River pipeline is the culmination of more than a decade of work to create a publicly owned city water system and then to finance and build a gravity supply system to bring water from the foothills of the Cascade mountains in southwest King County, rather than continuing to pump it from the increasingly polluted lakes surrounding Seattle. But the water actually arrives weeks ahead of schedule -- work is still underway when the pump station on Lake Washington that has been supplying Seattle breaks down, and water from the Cedar River pipeline is turned into the reservoirs and used until the pump is repaired. The Cedar River system will be formally placed into use more than a month later on February 21.

Looking to the Cedar

The Cedar River had been touted as a potential source of Seattle drinking water for more than two decades by the time its water first reached the city. In December 1880, the weekly newspaper Seattle Fin-Back predicted that by 1900 the Cedar would be Seattle's source of water. Mary McWilliams, a longtime Seattle water department employee who wrote a history of the department, described the Fin-Back article in a letter as "a fantastic allegory entitled 'A Modern Rip Van Winkle' which set the writer down in Seattle after a 20 year sleep, where he viewed a marvelous city. During the course of conversation with his carriage driver, it was announced that the water supply came from Cedar River" (McWilliams to Chilberg).

At the time of the Fin-Back article, Seattle was a small settlement of barely 3,500 souls, amply supplied with water from abundant springs and nearby lakes, and the idea of piping water from a mountain river miles away may have seemed as fanciful as that the population would reach 150,000 by 1900, which the Fin-Back also prophesied. Although City Surveyor F. H. Whitworth "went on record as favoring Cedar River" in 1881 (Bagley, 266), it was not until 1888 that Seattle took the first steps toward developing a Cedar River water system. By then the city was in the midst of a tremendous boom that would see its population increase more than tenfold for the decade.

This rapid increase not only strained the capacity of the private water companies that then served Seattle but also called into question the quality of the water that they pumped from lakes Washington and Union as increasing amounts of sewage and industrial effluent flowed into the lakes. In addition to water-quality concerns, relying on pumps was both expensive and problematic for fire protection. The cost of pumping water from the lakes up over Seattle's steep hills to its downtown and residential neighborhoods kept rates high, burdening consumers and slowing industrial development. The high rates also made it impossible for the city to afford a comprehensive system of fire hydrants, and the existing pumps lacked capacity to deliver the water needed to fight a major conflagration.

On September 24, 1888, Mayor Robert Moran (1857-1943), who had been elected that July, proposed a solution that would remedy all these problems: establish a city-owned water system that would draw clean uncontaminated water from the Cedar River high in the Cascade foothills and convey it downhill to the city using gravity rather than expensive pumps. The city council agreed and so did city voters, in an election held on July 8, 1889, one month after the Great Seattle Fire removed any doubts about the inadequacy of existing water systems.

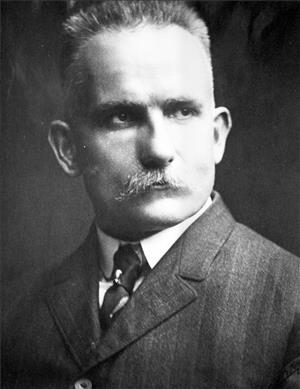

Benezette Williams

At Moran's suggestion, the city council hired Benezette Williams, a hydraulics engineer from Chicago, to study the feasibility and benefits of building such a system. Williams emphatically recommended building a gravity system rather than continuing to draw water from Lake Washington, where ongoing development meant ever-increasing levels of industrial waste and sewage:

"Nothing can be more certain than that all human excrement should be excluded from the source of every domestic water supply, and as it is impossible to do this in the case of Lake Washington, some other way for supplying the City of Seattle should be found" (Lamb, 35).

Williams outlined a gravity supply system that would begin with an intake at a dam to be built on the Cedar River about 29 miles from Seattle. A pipeline would carry 25 million gallons of water per day (enough for a population of 150,000 to 250,000, more than three to five times Seattle's population at the time) to two reservoirs in Seattle. Gravity and water pressure in the pipe would provide sufficient force to fill a "high service reservoir" on Seattle's Capitol Hill at an elevation of 400 feet. That reservoir in turn could distribute water to almost all the city by gravity, with pumps needed only for the few areas in the city higher than 350 feet. Although building the Cedar River system would cost somewhat more (around $1.2 million) than building a new heavy-duty pumping station on the lake ($685,000), the cost of operating those pumps would be more than $200,000 per year, compared to the minimal cost of maintaining the intake and pipes once built.

However, despite the clear advantages of a gravity supply system in both sanitation and long-term savings, Seattle in 1890 was not in a position to take on the large initial cost of developing that supply. Instead Mayor Moran and the council focused on the more immediately attainable goal of acquiring the Spring Hill Water Company (largest of the private companies) as the foundation of a city water department. Voters approved the purchase, and the Seattle Water Department began operating in November 1890.

The city water department made substantial progress in its first few years, but it came in expanding and upgrading the lake-based supply systems that Seattle had used for decades. Although both Benezette Williams and city officials had evidently assumed that Williams would oversee construction of the system he had planned, given fiscal realities that did not happen.

R. H. Thomson

Instead, building the Cedar River system would fall to others, foremost among them Reginald Heber Thomson (1851-1949) and Luther B. Youngs (1860-1923). Ambitious, driven, and visionary, R. H. Thomson was appointed City Engineer in 1892 by Mayor James T. Ronald (1855-1951) and held the position for two decades, during which he transformed the face of the city.

Despite bleak financial circumstances -- even before the Panic of 1893 plunged the region into a four-year depression, Seattle had borrowed up to the limit allowed by state law, leaving no apparent way to borrow funds to build the Cedar River project -- Thomson was so convinced that Seattle's future as a major metropolis depended on obtaining Cedar River water that within a year of taking office he and an assistant were in the field, following and revising Williams's planned route. Thomson believed that there had to be some way to rely on future revenue from the Cedar River system to pay for its construction. He assigned the task of figuring out what that way might be to George F. Cotterill (1865-1958), a surveyor and engineer who had previously worked with Thomson in private practice. Cotterill, a leading Progressive who would serve in the state legislature and as Seattle mayor and play a key role in forming the Port of Seattle, was, like Thomson, as much a social engineer as a civil engineer, and the two men shared a deep commitment to public ownership of utilities.

Despite their efforts, by early 1895 prospects for a publicly owned Cedar River system looked dim. That April a syndicate headed by New York financier Edward H. Ammidown offered to develop a private system on the Cedar River at its expense, and sell Seattle residents all the water and electricity they needed (at a profit to the investors, of course). Ammidown managed to win support from most of Seattle's wealthy leading citizens, many of whom had a stake in his proposed private water and power utility.

Unless Cotterill and Thomson could come up with some way for the city to fund construction of its own system, there would be little choice but to accept the offer from the private company. It was a Washington Supreme Court decision that provided a way forward. Like Seattle, the City of Spokane was building a new water system but couldn't issue bonds, having reached its debt limit. Would-be lenders proposed a novel solution: that Spokane issue "revenue bonds" to be repaid solely from the revenue that the water system produced. The court's August 1895 decision in Winston v. City of Spokane approved the then-novel method, and Seattle public-ownership advocates had, just in time, an alternative to the Ammidown plan.

An ordinance authorizing $1.25 million in revenue bonds to build a public Cedar River supply system went to voters on December 10, 1895. Unlike the nearly unanimous vote six years earlier following the Great Fire, the 1895 election was sharply contested, with most of the city's financial elite bitterly opposing the proposal. In addition to the fact that not a few had a personal interest in Ammidown's competing private utility, opponents were deeply suspicious of both the general idea of municipal ownership and the new-fangled concept of revenue bonds. Except in extraordinary circumstances (like the aftermath of the fire), much of Seattle's business establishment fiercely opposed public ownership of services or infrastructure in competition with private companies. And many opponents, even some who supported the public water system like former mayors Moran and Ronald, also genuinely feared that the novel and untried revenue-bond funding could lead to financial disaster for the city.

But Thomson was able to sway one key opponent to his side. Judge John J. McGilvra (1827-1903), a well-respected jurist and real-estate developer, initially opposed the bonds, but after meeting with Thomson changed his position and threw his resources into the campaign for the Cedar River ordinance. In the end, while not as one-sided as the 1889 balloting, the 1895 vote was overwhelmingly in favor of the ordinance: 2,656 votes to 1,665. The decisive outcome essentially ended the debate over whether Seattle's water supply should be privately or publicly owned.

L. B. Youngs

Public-utility supporters quickly followed up on their victory. A new city charter approved on March 3, 1896, provided for a future vote on establishing a city-owned hydroelectric plant on the Cedar River (the genesis of what would become Seattle City Light) and increased the authority of the water-department head (who would, until 1910, also head the hydroelectric project). Rather than being directed by a member of the Board of Public Works, the department would have its own superintendent appointed for a three-year term that could be renewed.

When the new charter took effect, L. B. Youngs had already headed the department for 13 months, longer than any of his seven predecessors. Mayor Frank D. Black then appointed Youngs to the new superintendent post, and numerous subsequent mayors extended his tenure. Youngs ended up leading the water department until his death in 1923, for a total of more than 28 years, longer than anyone else in the history of the water department or its successor, Seattle Public Utilities.

In that time, L. B. Youngs played a role second to none, not even R. H. Thomson, in developing and expanding both the Cedar River supply system and the in-city system of reservoirs, standpipes, pumps, and water mains that distributed the water to customers. Youngs worked closely and generally cooperatively with Thomson and succeeding city engineers to conceive, design, and build the system, and it was Youngs who took charge of managing and maintaining the completed works.

With leadership and authority to build in place, all that remained before beginning construction of the Cedar River system was to sell the $1.25 million in revenue bonds that voters had approved. The lingering effects of the depression made that impossible in 1896, but a year later the boom that followed the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897 made it easy to sell the bonds.

Building the System

Construction of the Cedar River system began in 1899 after contracts, based on plans that R. H. Thomson and his staff prepared, were awarded on April 19 of that year. Over the next year and a half, the Pacific Bridge Company built a headworks and intake on the Cedar River and a pipeline from the intake to the city. Another company -- Smith, Wakefield, and David -- constructed two reservoirs and a standpipe in the city, with the pipes and pumps connecting them.

The headworks was located at what came to be called Landsburg, after an early dam keeper, on the Cedar River approximately 28 miles southeast of Seattle and more than 500 feet above sea level. The Landsburg headworks consisted of a diversion dam across the river, a 54-inch wood-stave pipe intake, and a settling basin located beneath a gatehouse with manually operated screens and sluice gates designed to keep out large debris, along with a house for the dam keeper and a stable.

From the Landsburg intake, workers laid 28 miles of pressure pipe, capable of delivering 22.5 million gallons per day, to a high service reservoir being constructed in what was then called City Park (soon renamed Volunteer Park) on Seattle's Capitol Hill. Most of the line consisted of wood-stave pipe some three and a half feet in diameter. In sections where water pressure was particularly high, riveted steel pipe was used.

The City Park Reservoir held 23 million gallons and was 420 feet above sea level, allowing gravity distribution to almost all of the city. Less than a mile south, a second, lower reservoir, with nearly the same capacity and an elevation of 316 feet, was also built on Capitol Hill, in a park then known as Lincoln Park. (In 1922, the name Lincoln Park was applied to a large West Seattle park and, after several intervening names, the Capitol Hill park was named in 2003 for state legislator Cal Anderson [1948-1995].) The two new reservoirs provided a combined capacity 10 times that of the city's existing 4.5 million-gallon reservoir on Beacon Hill. In addition, a 318,000-gallon standpipe was built at an elevation of 512 feet on Queen Anne Hill. A pump station at the Lincoln Reservoir was installed to pump water to the standpipe and other parts of the city too high to be served by gravity.

Cedar River Water Arrives

Construction was largely completed by the end of 1900. That Christmas Eve, First Assistant Engineer Henry W. Scott turned water into the pipeline for testing. Slightly more than two weeks later, on January 10, 1901, Seattle residents used Cedar River water for the first time. The historic day, although many years in the making, actually came more than a month ahead of schedule. Final work and testing were still underway when the pump at the Lake Washington pump station broke down. For a few days beginning on January 10, water from the Cedar River pipeline was temporarily turned into the reservoirs and used until the lake pump was back in service.

The Cedar River system was placed into regular use on February 21, 1901, when the Board of Public Works formally accepted Smith, Wakefield, and David's work on the reservoirs, standpipe, and pump station, after official tests on the new pumps showed that they exceeded contract specifications. Before June, the old pump stations on Lake Washington and Lake Union were taken out of service.

When L. B. Youngs issued his annual report for 1901, he noted that the Lake Washington pump station was back in use, for a different purpose: it had been leased to the Seattle and Lake Washington Waterway Company, which used the water in its ongoing project to fill Elliott Bay tideflats south of downtown Seattle by sluicing earth from Beacon Hill. The report noted that the two new reservoirs and standpipe, along with the existing Beacon Hill reservoir, together held slightly more than 50.5 million gallons of water. This represented a more than tenfold increase in storage capacity, but there was no problem keeping the reservoirs full. Youngs explained that, unlike in earlier years, it was not possible to give the total amount of water consumed for the year. The city then had no means -- and no need -- to measure the total amount of water flowing from the Cedar River.

As it turned out, the "surplus" water pouring through that first Cedar River pipeline was not surplus for long. Thomson soon put much of it to use in a series of massive regrading projects, sluicing down many of the hills that surrounded, and in his view confined, downtown Seattle. Between the regrading work and Seattle's continuing population boom (a nearly 200-percent jump in the first decade of the twentieth century), by 1905 Youngs was calling for a second pipeline. Construction of that line began in 1908 and it was delivering Cedar River water by 1909. A third pipeline was added in 1926 and a fourth came on line in 1954. In the 1960s, the Seattle water department inaugurated a second supply from the South Fork Tolt River in northeast King County, but well over a century after it first reached Seattle reservoirs, Cedar River water continues to supply Seattle and many surrounding communities that obtain water from Seattle Public Utilities.