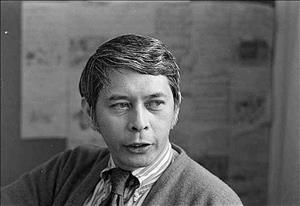

Bob Santos (1934-2016), born and raised in Seattle's Chinatown-International District, spent most of his life as an activist in his old neighborhood -- saving it, nurturing it, defending it against outside threats, whether environmental, cultural, or political. Considered the unofficial mayor of the ID and known to most as Uncle Bob, he was arrested six times fighting for civil rights. Not always an outsider, Santos during the Clinton administration served as the Pacific Northwest's Housing and Urban Development director. On July 30, 2014, he sat down for an interview with HistoryLink.org intern Alex Cail and that interview is presented here in four parts. In Part 1, Santos talks about his difficult youth, lightened by a vibrant music scene; his involvement in the civil rights movement, starting in the 1960s; the effort to integrate the construction trades in King County; and the struggle to secure equal pay and improved working conditions for Asian (mostly Filipino) cannery workers in Alaska. The interviewer's questions are not included, and the transcript has been slightly edited for clarity and length.

Life in the International District

I grew up in the International District. My father was a professional prize-fighter, a boxer, and actually met my mom down here. She was attending school at the University of Washington and working part-time as a waitress [in the International District]. He was this big sports hero in Seattle, and he kept going back to the restaurant where she worked. It was called the Resolve Café. It was on the corner of Maynard and King, in the middle of Chinatown. We also referred to it as the old "Manilatown." They were married and had two children, my brother and me, and then she contracted tuberculosis, so she passed away, very early. She was 23 years old when she passed away.

In 1945 my father lost complete use of his eyes, due to boxing injuries. So I was his seeing-eye dog, and I'd take him all around his old haunts: the gambling halls, the barbershops, the restaurants, all through the Chinatown-International District area. So I got to know a lot of the people who owned businesses and a lot of the kids that were also living down here. Most of the families that lived down here -- Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos -- lived in highrises, like this building [the Panama Hotel]. We called them SRO -- single room occupancy units -- so if there was a family, they would rent maybe two rooms. Separate rooms. And we had one room next door at the NP Hotel.

Growing up here was very interesting because Jackson Street during the '20s and '30s and into the '40s was the jazz capital of the coast. There were 23 jazz clubs up and down Jackson Street -- right here -- and a few up on King Street, a couple on Maynard, a couple on 6th, but Jackson Street was really a hotbed for jazz. The reason was, this was the end of the continental railroad. It went from east to west, and ended up here in Seattle coming west. The black workers on the railroads -- the porters, the cooks -- they would stay between trips, here in the International District, so it drew the jazz musicians to the area. So I got to experience all of this music growing up, all the time.

The Civil Rights Movement

Going back into the '60s, now, I started getting involved in the civil rights movement, mostly with the black experience. I was executive director of an organization called CARITAS. It was a tutoring program based in the Central Area of Seattle, so we tutored young black kids that were having problems in math and reading at school. We tutored them on a one-to-one basis. And while doing so we were located in an old school and church called St. Peter Claver Center.

I had the largest office in that complex, so they had me sort of manage the building. And we had the little auditorium -- seated maybe 100 people, 120 people, maybe a little larger. And the organizations that were starting up then in the civil rights movement -- black organizations, Asian, Native American -- they would meet with their membership and recruit members at the St. Peter Claver Center auditorium. So I got to meet all these leaders in the new, the ever-growing civil rights movement, and I started going on demonstrations with them.

There was one person in particular that was, probably, the most prominent leader in the civil rights movement at that time, in the late '60s and '70s. His name was Tyree Scott, and he was a construction worker -- he was actually an electrician. And he would gather young black construction workers, or young black males who wanted to work in the construction industry. But at that time, minorities were barred from entering the unions, or they were passed over when there were openings in the construction jobs.

Tyree would drive around the community, the Central Area, and if he found a construction site where there were no minorities, the next morning he would go back to that site with five or six of these young guys looking for work, and they'd shut the job down. And that started a movement with activists who were starting to join Tyree -- not that they wanted jobs -- but they were fighting to open up the industry to other minorities. Those construction jobs started to grow. From single-family housing that they were building, to apartments, and then to commercial and federally funded office buildings.

There was a shutdown of a project at the University of Washington. There was a shutdown -- probably the largest demonstration -- at Seattle Central Community College when they were building the new administration building and classrooms on Broadway. I don't know if you are familiar with that, but Broadway and Pine, there was a whole week of demonstrations at that site, and I joined them and actually, I got arrested with Tyree and many other activists during that week.

But that really started to bring this issue to the attention of the media and elected officials. Because, we're talking about the late '60s and going into the '70s, and one thing that you find out that politicians just hate is bad publicity. So if your city is in turmoil, and your elected officials turn the other way or do nothing about it, they get a bad name.

And the City itself, the City of Seattle, was starting to [notice] the issue of equal opportunity in the construction industry. So that was changing. The unions and the construction industry had to change. They had to start ... and through a court order, through Judge Lindberg's court, in the early '70s, he made a decision that a percentage -- I forget the percentage now -- but a percentage of young black males were to be included in apprenticeship programs in all the elements of the union. So that started the move towards more equal opportunity for minorities.

The Cannery Workers' Fight

The organization that Tyree headed was called the United Construction Workers Association, and with the success of that organization into the construction industry, Tyree started organizing Asians, particularly Filipino-Americans, who were sent annually to the seafood canneries in Alaska. During the salmon runs at this time, most of the Filipinos were flown into Alaska, into the canneries, and they worked to process the fish. When I was a junior and senior in high school, I was able to join one of those cannery jobs.

Right away you knew there was something a little bit different, especially if you were a minority worker. There were white fishermen, there were white men, mostly all men, working as machinists and in the warehouses, and these were pretty good-paying jobs. The Asians, the Filipinos, were relegated to working in the fish-house, they're the ones that cut up the fish, and put 'em in cans, and all that kind of stuff, and they were very low-paying jobs. So when some young Asians started to question whether they would be eligible to apply for the higher paying jobs, they were told "No."

And that also changed in a couple of lawsuits, class-action lawsuits. Not only that, but there would be two mess-halls -- one for the whites, and one for the Asians. And the whites, of course, they had pork chops, and steak, and breakfast, they'd have sausages, and all the good stuff you'd get in a good restaurant. And the Filipino mess hall, was fish and rice, fish heads -- salmon heads -- and rice. And some vegetables. Sometimes on Sunday you get chicken. So there was a disparity there, in terms of meals that were prepared. One side gets everything, and the other side just gets enough to get through.

Housing was also segregated. There'd be a set of cabins, where I went. A set of cabins was probably two to four white workers per cabin. Down the boardwalk, at the end of the boardwalk, was a bunkhouse, and the Filipinos were segregated from the white population -- even in distance -- at the end of the boardwalk. And they had eight cannery workers -- eight of us -- living in one room. Eight in one room. All through that bunk house. So we were no one. You had bunks on both sides, and just enough room through the aisle for one person to pass. So someone wanted to go outside the room, everybody had to sit, or lay on their bunks while the other guy walked through, 'cause there was no room to even pass. So that was also considered blatant segregation.

All of the white workers were in good-paying jobs. The warehouse, the white workers in the warehouse, and they were machinists, mechanics, and the Filipinos were in the fish house. So I got that experience of working in this segregated environment. I learned right away the issues that were involved in the civil rights movement.

In terms of employment opportunities, the Filipinos could either work out in the fields, doing farm labor at very minimal pay. You could be a busboy, or a waiter, or a dishwasher, or a cook. There weren't that many opportunities out there for minorities at that time. We're talking about the '50s and '60s, into the '70s. Even though there was segregation in the canneries, if you went through the union -- which was run by Filipino union officials -- you still got guaranteed contracts, you got, I think it was $1,200, my guarantee was $1,200 a month, guarantee whether there were fish or not. And if there were a lot of fish then you work overtime and you would make more money. So, compared to the alternative, working on the farms, this was more lucrative because you got paid at the end of the season, and you could come home with $2,000, almost $3,000 dollars. So that was pretty good.

Then into the '70s there were young Asian activists that started to rebel, even while they're in Alaska. They would be requesting elevation into the higher-paying jobs, and they were rejected. So all that was being documented. And then that was used in the class-action lawsuits against the seafood industry. You can start by looking up Workers vs. New England Seafood, New England Fish Processing. And there's another company called Ward's Cove, and if you look that up you can find out more about the lawsuits.

To go to Part 2, click "Next Feature"