The Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) was created in 1937 as a temporary agency with a limited mission: to market and distribute electricity from Bonneville Dam, on the Columbia River. Its supporters expected that it would soon be replaced by a comprehensive planning entity like the Tennessee Valley Authority. Repeated efforts to establish a Columbia Valley Authority failed, as did later efforts to dismantle BPA. The agency sold electricity at rock-cheap prices and urged people to use it with abandon. It promoted the construction of more dams as a way to satisfy the demand it had helped stimulate, and then, when the river was virtually dammed up, it made a disastrous multi-billion-dollar bet on nuclear power. Congressional mandates in the 1980s pushed it toward energy conservation and the restoration of fish runs that had been decimated by the dams. Today BPA sells and delivers power from 31 dams, one nuclear-power plant, and several wind farms; owns and operates a 15,000-mile high-voltage transmission system; and finances what may be the world's most expensive fish recovery program. It's been called "large and boring" (White, 72), but perhaps no other federal agency has been a greater catalyst for change in the Northwest.

Controversial Birth

The agency was born during a time of intense debate about how power from the soon-to-be completed Bonneville Dam should be sold and distributed. Public Utility Districts wanted the power to be widely dispersed at uniformly low rates over government-built transmission lines. Supporters of private power objected to any distribution system that would favor public over investor-owned utilities; they wanted the government's involvement to end at the "bus bar" (basically at the generating plant). Advocates of long-range planning wanted both Bonneville and Grand Coulee Dam (which was also under construction at the time) to be managed by a Northwest version of the Tennessee Valley Authority; such an agency would not only sell and deliver electricity, but would have broad responsibilities for regional land use and social and economic development.

All these issues and more were debated during a series of Congressional hearings held between March and June 1937. The Bonneville Project Act that emerged after the hearings was a compromise. It created a new federal agency to market electricity from Bonneville and build the transmission system to deliver it to utilities who would, in turn, distribute it to retail consumers. The dam itself would be maintained and operated by its builder, the Army Corps of Engineers. The agency's administrator would report to the Secretary of the Interior. The administrator would set wholesale power rates subject to approval by the Federal Power Commission. The act made it clear that the agency -- originally called the Bonneville Project -- was "intended to be provisional pending the establishment of a permanent administration for Bonneville and other projects in the Columbia River Basin" (sec. 2-a).

President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) signed the measure on August 20, 1937. Three years later, he issued an executive order that changed the name of the agency to the Bonneville Power Administration and added the sale and transmission of power from Grand Coulee Dam to its duties. As other federal dams on the Columbia and its tributaries came on line, they too were placed under BPA's jurisdiction. Meanwhile, Congress considered at least half a dozen bills to replace BPA with a Columbia Valley Authority; none passed.

The Bonneville Power Act included two key elements that had enormous impact on the development of the federal power system, both in the Northwest and elsewhere. The first, found in Section 4(a), has come to be known as "the preference clause." It directed the agency to "give preference and priority to public bodies and cooperatives" in delivering electricity. The second, found in Section 6, established the principle of uniform or so-called "postage stamp" rates for BPA power. Just as it costs the same to send a letter to a house down the street or across the nation, a postage stamp electric rate is a fixed charge no matter how far the energy has to be transmitted from its source. Uniform rates ensured that the entire Northwest would benefit from the huge federal dams being built on the Columbia.

The law also directed that revenue from the sale of power be used to repay the government for the cost of building the dam (and later the other dams), amortized over a 40-year period. In addition, BPA was required to be self-supporting: No tax money would be available to finance its daily operations. To ensure sufficient revenue to meet these obligations, the agency was to "encourage the widest possible use of all electric energy that can be generated and marketed" (Bonneville Project Act, sec. 2[b]).

Portland, Oregon -- 40 miles west of Bonneville Dam -- was designated as the agency's headquarters. A liaison office was established in Washington, D.C. It's been said that BPA is the only federal agency of any size that has only a branch office in the nation's capital.

Early Steps

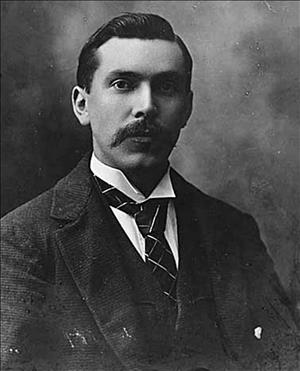

James D. "J. D." Ross (1872-1939), longtime superintendent of Seattle City Light, had a short but influential tenure as Bonneville's first administrator. A charismatic proponent of hydroelectric power, he was often quoted as saying "a great river is a coal mine that never thins out. It is an oil well that never runs dry" (Springer, 33). He predicted that the Columbia would become "the power house for a large part of the United States," and that "Eventually, hydroelectric energy will be as cheap as air or water" (Neuberger, "Prophet").

Bonneville Power did not have any power to sell during most of its first year. Instead, its major tasks were to design a transmission system and to determine the rate for electricity delivered over that system. Chief Engineer Charles E. Carey (1890-1945) oversaw the former; Ross, the latter.

For Ross, the challenge was to set a rate that would be low enough to encourage consumption but high enough to make sure the agency had enough revenue to cover its operating costs and its required payments to the U.S. Treasury. He was under enormous pressure from the Portland business community to adopt a "bus bar" rate, meaning that power would be cheapest in areas closest to the dam and rise proportionately as the distance increased. He ultimately recommended a uniform rate of $17.50 per kilowatt year (about one-fifth of one cent per kilowatt hour). However, he also recommended that customers within 15 miles of the dam who built their own transmission lines be charged a rate of $14.50 per kilowatt year. The Federal Power Commission approved those rates on June 8, 1938. They would not be increased for 27 years.

Carey, meanwhile, was creating the blueprint for a "master grid" that would tie the Northwest together with loops of high-voltage wire. His initial plans called for the construction of 2,737 miles of wire and 55 substations linking the urban centers of the Northwest -- Portland, Seattle, and Spokane. The network would eventually include more than 15,000 miles of line, stretching north into Canada and south to California. The first small segment was energized on July 9, 1938. Appropriately enough, it delivered power to a public utility: the city of Cascade Locks, 3.5 miles from Bonneville Dam.

Ross submitted his first (and what would prove to be only) annual report to Congress on December 1, 1938. In a prescient note, he emphasized the importance of power to national defense. "Modern warfare is fought in the factory as much as in the air or trenches," he wrote. "America must be ready to meet not only peacetime needs of power for home, farm and industry, but must be assured of her ability to cope with emergency demands for large blocks of electricity" (First Annual Report, p. 20).

He died on March 14, 1939, of complications after undergoing abdominal surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota -- on the eve of the outbreak of World War II in Europe.

Customers Wanted

Ross was succeeded by Paul J. Raver (1894-1963), who would hold the position for 15 years (longer than any other administrator in BPA history). Raver was an Indiana-born economist who left a position as chair of the Illinois Commerce Commission in Chicago to join BPA. He was a strong proponent of public power but had never set foot in the Northwest. He had to refocus an organization that had been shaken by the sudden death of his much-admired predecessor; rapidly expand the staff to keep up with the construction schedule for the transmission network; encourage the formation of Public Utility Districts (PUDs); and, above all, find customers for the burgeoning amounts of power that were coming on line from Bonneville and, beginning in 1941, from Grand Coulee dams.

Construction of the dams had been justified in part by the argument that the costs of building them would be covered by selling the electricity they would generate. In its quest for markets, BPA began to function "like a highly skilled, multi-state, regional, chamber of commerce" (Kramer, 60). Staff economists and other personnel inventoried the region's natural resources (including hydropower), identified potential areas for development, formulated business plans, and presented them to established national companies.

The first target was the energy-hungry aluminum industry. BPA worked aggressively to create "a vertically integrated, competitive, permanent, and prospering aluminum industry in the Pacific Northwest" (Stein, 3). Vertical integration meant bringing all the stages of aluminum production into the Columbia River Basin, including mills to process bauxite (the principal ore of aluminum) into alumina; smelters to reduce alumina into metal ingots; and semi-fabrication plants to roll or cast the ingots into bars, sheets, or other forms to sell to manufacturers. The agency signed its first major sales contract on December 20, 1939, with the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa). The company opened the Northwest's first aluminum smelter on a 218-acre site near Vancouver in 1940. It bought most of the electricity that BPA had to sell that year.

"Roll Along Columbia"

BPA's function and future remained "grimly contested" throughout its early years (Stein, 5). Bills to dispose of it, transfer its marketing duties, or replace it with a more comprehensive organization were regularly, and bitterly, debated in Congress. Critics attacked BPA in particular and public power in general as socialistic, anti-business, and anti-American. Voters in Spokane, Tacoma, Portland, and Eugene rejected measures to replace investor-owned, for-profit private utilities with PUDs. Several counties in Washington and Oregon began building their own, non-federal dams on the Columbia and its tributaries. This was the context that put folksinger Woody Guthrie (1912-1967) on the BPA payroll for one memorable month in the spring of 1941.

Guthrie was hired at the behest of Stephen B. Kahn (1911-2007), the agency's first public information officer. Kahn had produced a short promotional film called "Hydro" in 1939. The reaction was lukewarm. He decided to make a second, feature-length film, to be called "The Columbia: America's Greatest Power Stream." The goal was to dramatize the value of Bonneville and Grand Coulee Dams and their benefits for workers, consumers, and industry. Kahn believed that having a folksinger involved would make the film more appealing. He asked Alan Lomax (1915-2002), folk music archivist at the Library of Congress, to recommend someone; Lomax told him to contact Guthrie, who was in Los Angeles, unemployed, at the time.

Guthrie got the job after being interviewed by a BPA emissary in Los Angeles, filling out half a dozen forms (including a loyalty oath), and, finally, auditioning for Administrator Paul Raver in Portland. With Raver's approval, Guthrie was hired as an "information consultant" for 30 days beginning May 13, 1941, at a salary of $266.66 (one-twelfth the standard laborer's annual wage). Kahn originally intended for Guthrie to narrate and act in the film as well as write songs for it, but later decided to have him focus on music alone.

A BPA employee named Elmer Buehler (1911-2010) drove Guthrie around the Northwest for about a week. "He wasn't long on conversation," Buehler recalled. "He seemed preoccupied with his guitar and his songs" (Buehler Statement). Back in Portland, Kahn told Guthrie he had to produce three pages of lyrics every day. By the end of the month, Guthrie had written 26 songs, some cobbled together with recycled bits from earlier work, some with new words written to familiar folk tunes, but together constituting a "26-song toast to electrified democracy" (Lomax, 1987). The most famous of these was "Roll On Columbia, Roll On," sung to the tune of "Goodnight Irene" and later adopted by the state legislature as the official folk song of Washington. But it was in "Ballad of the Great Grand Coulee" that Guthrie most eloquently celebrated the government's role in harnessing a "wild and wasted" river. "Roll along, Columbia, you can ramble to the sea," he wrote, "but river, while you're rambling, you can do some work for me."

In the end, only three of Guthrie's songs made it into the film. Production was delayed by the U.S. entry into World War II. The film was not released until 1949. Four years later, in the midst of renewed debate about the role of BPA, a new Republican administration ordered all copies of "The Columbia" and other promotional material to be incinerated. Buehler, who was by then working as a janitor for BPA, hid one copy of each of the two films and kept them in his basement in Portland for years. He later donated them to the National Archives.

Power Surge

Any concern about finding markets for BPA power vanished during the war. As Ross had predicted years earlier, modern warfare demanded huge blocks of power. BPA's high-voltage grid became the highway that fed power to shipyards, aircraft industries, food processing plants, and the booming aluminum industry. By 1943, 12 large aluminum plants were operating in the Northwest, producing massive quantities of strong, lightweight metal for bombers and fighter planes and soaking up 60 percent of the power sold by BPA.

The longstanding battle between investor-owned utilities and those operated by municipalities or PUDs was suspended, at least temporarily, in 1942, when the War Production Board ordered that public and private electric output be pooled as a defense measure. BPA became part of the Northwest Power Pool, a network that had been established by a consortium of public and private utilities in 1941. BPA Administrator Paul Raver had proposed the creation of such a pool as early as 1939, although some public-power advocates remained wary. Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes (1874-1952), for example, warned that public power might find itself "a Laocoon in the death grip" of interconnections with private power after the war ended (Voeltz, 75). (Laocoon was a figure in Greek mythology who was attacked by giant serpents.) Still, by pooling their generating capacity and sharing transmission lines, "the utilities of the Northwest were able to utilize an additional 100,000 kilowatt hours of power through increased efficiency, all without building a single plant" (Kramer, 60).

Defense-related industries demanded every spare kilowatt BPA could provide. Shipbuilders, for example, wanted power for the new, high-voltage arc welders that were being used instead of rivets on the hulls of battleships. In March 1943, the War Production Board ordered BPA to make up to 150,000 kilowatts available to an unnamed project, shrouded in secrecy, in southeastern Washington. It was later revealed that the mystery load was going to the Hanford Nuclear Works, which produced the plutonium for the bomb that was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945. World War II ended with the surrender of Japan five days later.

Even before the end of the war, BPA officials began preparing for anticipated cutbacks in demand. In March 1944, the agency's Advisory Board asked Congress for a supplemental appropriation of $254,000 to pay for "remarketing" studies. Congress appropriated exactly half that amount, for the fiscal year 1945. By that time, shipyards, aircraft manufacturers, and other large-scale industrial users were already curtailing production. Sales at the Boeing Airplane Company dropped from $600 million in 1944 to $14 million in 1946. "It became an urgent problem to find other markets to take up the impending slack," a BPA historian noted (Davis, Supplementary Material, 14).

Three large aluminum smelters and one rolling mill had been built in the Northwest by the Defense Plant Corporation, a part of the federal Reconstruction Finance Corporation, early in the war. By the end of 1945, all of them were idle, and operations at the region's private plants were greatly reduced. BPA's revenues dropped by 35 percent. Partly as a way to encourage competition within the aluminum industry, and partly to protect its own financial future, BPA invited the Reynolds Metals Company and the Permanente Metals Company (forerunner of Kaiser Aluminum) to bid on the shuttered government-built plants. The companies bought the plants, "at fire-sale prices," and brought all of them back up to full production (Stein, 12). By 1947, the aluminum industry was using almost as much of Bonneville's power as it had during its wartime peak.

BPA worked to retain as many industrial users as it could, but it also put new effort into encouraging the formation of PUDs and rural electric cooperatives. It distributed promotional materials to stimulate consumer demand for new appliances and labor-saving devices, better lighting, and electric heating. By 1952, 97 percent of the farms in BPA's service area had access to electricity (compared to fewer than half a decade earlier). Electric water pumps, milking machines, grain augers (for moving grain from truck to silo or bin), washing machines, irons, and so forth made life easier for farm families and helped BPA sell a little more power. Even so, the aluminum industry continued to be BPA's biggest client, accounting for roughly half the electricity the agency sold for the next three decades.

Private vs. Public, Redux

BPA entered the 1950s in a precarious position, financially and politically. The agency's efforts to promote public power brought it back into conflict with private utilities. The controversy was amplified by renewed efforts to create a Columbia Valley Authority (CVA). Bills to establish a CVA were introduced in 1944 and again in 1949, in the latter case by Henry M. "Scoop" Jackson (1912-1983), then a young Democratic U.S. Representative from Everett, later an influential senator. President Harry Truman (1884-1972) supported Jackson's bill but the private power lobby staunchly opposed it. One critic called it "a prime example of creeping socialism" (Miller). A Republican Congressman from Iowa specifically blamed the "motley forces of Marxism" for the "socialistic policies of the Bonneville Power Administration" (quoted in Kramer, 68). The measure was soundly defeated, as was yet another CVA bill, sponsored by Oregon Democratic Senator Richard Neuberger (1912-1960) in 1958.

BPA found fewer allies in Washington, D.C., after the election of Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) in 1952. Eisenhower appointed Douglas McKay (1893-1959), a former governor of Oregon and strong supporter of private power, as Secretary of the Interior. Paul Raver, a longtime champion of public power, resigned as BPA administrator and was replaced by William A. Pearl. In "a satisfying bit of symmetry," Raver was appointed superintendent of Seattle City Light, the position that J. D. Ross had left in order to become BPA's first administrator (Kramer, 74).

During the next two decades the federal government continued to build dams that fed power into the BPA system, but all of them had been authorized by Congress before 1950. One dam, at Priest Rapids on the middle Columbia, had been authorized as a federal project in 1950 but was de-authorized in 1954, in order to clear the way for its construction by the Grant County PUD. Bills introduced in Congress in 1954 and again in 1955 would have de-authorized the John Day Dam on the lower Columbia. The bills were defeated. John Day and Lower Granite, on the lower Snake, completed in 1971 and 1975 respectively, were the last of the big federal dams. PUDs developed the rest of the main stem and investor-owned utilities plugged most of the tributaries.

With an increasing number of non-federal dams under construction in the late 1950s, BPA officials became concerned that the federal grid would soon face competition from separate, privately owned networks. They proposed a solution that essentially allowed private utilities to rent time on the BPA network, through "wheeling" (a process in which electricity generated by one utility is transmitted over facilities owned by another utility, or, in this case, a government agency). Much study ensued. Congress finally agreed that wheeling was authorized by Section 2 of the Bonneville Project Act and passed a law affirming it; Eisenhower signed it in August 1957. The arrangement was mutually beneficial. The utilities had to pay BPA for the use of its lines but the rates were less than the cost of building their own transmission system. BPA, for its part, gained a welcome source of revenue.

Interconnectivity

BPA was in need of new revenue partly because of the high cost of its share of building the new dams. Although as of 1962 it was still $20 million ahead of schedule in meeting its required payments to the Treasury, it had experienced four straight years of annual deficits, severely cutting into the accumulated surplus. The agency urgently needed new ways to pull more kilowatts from the river and find new markets for those kilowatts. The remedy was two-fold: the Columbia River Treaty with Canada, ratified in 1964, which increased the amount of power available to BPA; and the Pacific Northwest-Pacific Southwest Intertie, which gave it access to power-hungry customers in California.

The Columbia River Treaty was an effort to "rationalize" the natural fluctuations in the Columbia River system. Patterns of rainfall and snowmelt meant that river was at its highest, and could produce the most electricity, in the spring and summer. However, the demand for power in the Northwest was highest in the fall and winter, partly because of the popularity of electric heating. For ideal power production, water would be stored in reservoirs during periods of high flow, then released when needed to generate electricity. Of the many dams on the main stem of the Columbia within the United States, only one -- Grand Coulee -- had the capacity to store water for release later. That dam, as large as it was, could not hold back the Columbia at full flow. The excess water had to be spilled over the tops of downriver dams instead of being used to turn generators.

Charles F. Luce (1917-2008), a Walla Walla attorney who had been appointed BPA administrator in 1961, summed up the problem in his first annual report. "Ironically, in each of our deficit years," he wrote, "we have been forced to waste some $30 million worth of water per year over our spillways -- water that could have turned generators, produced kilowatt hours and revenues, and converted red ink into black had there been a Northwest market for this kind of power" (1962 Annual Report, p. 5).

There were no more unclaimed storage sites on the main stem within the U.S. and only limited potential on the tributaries. Within Canada, however, there were a number of undeveloped damsites. Under the terms of the Columbia River Treaty, Canada built two large storage dams on the upper Columbia and a third on a major tributary, the Kootenay (spelled Kootenai in the U.S.); the U.S. was permitted to build Libby Dam, on the Kootenai in western Montana, which backs up water into Canada. The upriver storage made it possible for the American dams to generate an additional 2.8 million kilowatts of "firm" (uninterrupted) power -- roughly equivalent to another Grand Coulee.

There remained the problem of marketing the power. "Despite recent intensified efforts to sell more of this capacity inside the region," Luce concluded, "it is clear we will have to look outside the region to find markets for the System's total power capability" (1962 Annual Report, p. 5). This argument helped give traction to long-sought Pacific Northwest-Pacific Southwest Intertie.

The intertie (basically an interconnection between utilities) had been suggested as early as 1919 by C. Edward Magnusson (1872-1941), professor of electrical engineering at the University of Washington. He proposed building a 220-kilovolt line from the Canadian border to Los Angeles, to connect Washington and Oregon with California's transmission lines. The Pacific Northwest Regional Planning Commission endorsed the idea in a 1935 report on the Columbia Basin. J. D. Ross included it in his 1938 "master plan" for the BPA system. Bonneville's chronic deficits helped make the plan a reality in the 1960s. Luce predicted that BPA could make an extra $6 million to $15 million a year by selling power to California. Congress appropriated $45.5 million to begin construction in August 1964, but at the same time, it passed a bill stating that only power that was not needed in the Northwest (Washington, Oregon, and Idaho and those parts of Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and Nevada which drain into the Columbia River) could be sold outside the region.

Betting on Nuclear

By the late 1960s most of the available kilowatts had been sucked out of the Columbia River system. BPA planners turned to the atom, convinced by what proved to be wildly inflated forecasts that hydropower alone would not be enough to meet future demands. In 1968, in conjunction with the Joint Power Planning Council, BPA unveiled a new master plan: the Hydro-Thermal Power Program, calling for the construction of 20 nuclear power plants, two coal-fired plants, and additional generating capacity at existing dams.

The first phase of the 20-year project included three nuclear plants to be built by the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS -- pronounced "Whoops" -- a consortium of 17 public utilities) and financed by BPA. Under federal law, BPA could not build or own the plants directly. Instead, it proposed to finance them through a complicated accounting system called "net billing." Revenue bonds to build the plants would be issued by WPPSS but guaranteed by BPA, in the expectation that the costs would eventually be recovered by selling the power from the completed plants. The agency signed its first contract with WPPSS in 1971, for the construction of what was called Project 2, to be built at Hanford. Contracts for Project 1, also at Hanford, and Project 3, to be built at Satsop, were signed in 1973. Under the net billing concept, BPA was obligated to pay the costs of building all three plants whether they ever produced any electricity or not.

The cost overruns began almost as soon as the contracts were signed. To cover its share of the increases, BPA was forced to raise its wholesale rates for only the second time in its history, by 27 percent, in December 1974. The previous increase, in 1965, had been a modest 3 percent. Ratepayers, especially industrial users, began to express concerns about the rising costs at the WPPSS plants as well as at the Trojan nuclear plant, a Portland General Electric project being built in Oregon with partial financing by BPA. The agency's faith in nuclear power remained undimmed. Donald P. Hodel (b. 1935), appointed BPA administrator in 1972, applauded plans to add two more reactors to the WPPSS portfolio: Projects 4 and 5. He thought it was unfortunate that because of a ruling by the IRS, BPA would not able to finance the construction of those plants through net billing; WPPSS had to assume the full risk.

In blunt messages to the region's utilities, Hodel told them to get on board Projects 4 and 5, and quickly, or face cutbacks. As for environmentalists and other critics of nuclear power, they were "Prophets of Shortage," he said in a speech in Portland in July 1975, "on a collision course with the growing demand for energy ... dedicated to bringing our society to a halt ... anti-producers and anti-achievers," advocating "scarcity and self-denial" (quoted in Harrison, "Hydro-Electric ...").

Hodel left BPA in December 1977. He would go on to serve as Secretary of Energy and then as Secretary of the Interior for President Ronald Reagan (1911-2004). His successors at BPA were left to deal with the consequences of his enthusiasm for the Hydro-Thermal Power Program.

Legacy of Debt

BPA ended the 1977 fiscal year with a then-record deficit of $55.9 million, followed by deficits of $17 million in 1978 and a staggering $70 million in 1979. Under contracts negotiated during its last rate increase, in 1974, BPA was not able to raise rates again until 1979. That year, it shocked consumers and soured relations with industrial users by implementing an 88 percent rate increase. "Customers and the general public have shown keen interest in the reasons for the large BPA rate increase," the agency noted, with considerable understatement, in its 1979 Annual Report (p 34). That increase was followed by three others, in quick succession: 61 percent in July 1981, 54 percent in October 1982, and 22 percent in November 1983 -- a six-fold increase in just four years. The agency suspended its payments to the Treasury during that period, deferring a total of $218 million before getting back on schedule in 1984.

Meanwhile, the dire power shortages that BPA had been forecasting for years failed to materialize. Industries, businesses, and consumers responded to the cluster of rate increases by cutting back on energy use. A new forecast, released in 1982, predicted surpluses, not shortages. "We had been over-forecasting for some time and had failed to take into account market changes," said BPA Administrator Peter T. Johnson (1932-2014), who took over the troubled agency in May 1981 (Power, 16).

It was Johnson, a businessman from Boise, Idaho, who finally pulled the plug on what is widely known as "the WPPSS debacle." He had been in office for only days when WPPSS released new estimates, saying the five planned plants would cost $24 billion -- $5 billion over the last estimate and a 340 percent increase over what they were originally expected to cost. And now it appeared that they wouldn't even been needed. With no way to control costs and no end in sight, Johnson ordered that work on Projects 1 and 3 be halted. The world had changed, he told the WPPSS board in a meeting in Seattle, and given the lower demand for power, he would not approve a budget for continuing the two projects.

The decision meant that about 6,000 workers would lose their jobs. Johnson needed police escorts as he traveled around the region to explain the reasons for his action. He was jeered by several thousand people at WPPSS headquarters in Richland in April 1982 and then hung and burned in effigy. More than 300 union craftsmen crowded into an auditorium in Seattle later that month, where he was excoriated by speaker after speaker and then presented with piles of letters written by children, with messages like "Mr. Johnson, please don't fire my daddy" (Power, 21).

In the end, only one of the five proposed WPPSS plants was completed. Project 2, the first to be backed by BPA, went on line in 1984, at a final cost of $3.2 billion (compared to an initial estimate of $465 million). It remains in operation (as of 2015) as the Columbia Generating Station. The Trojan plant was completed in 1976 but closed in 1994. BPA financed 30 percent of the cost of that plant. In all, the agency's investment in nuclear power left it with about $7 billion worth of debt. Servicing the debt costs ratepayers about $600 million a year; it is not expected to be paid off until 2044.

Pivot Point

Johnson also faced the challenge of implementing the Northwest Power Act (officially the Pacific Northwest Electric Power Planning and Conservation Act), a milestone that required BPA to pivot toward conservation and protection of fish and wildlife. The law, signed by President Jimmy Carter (b. 1924) on December 5, 1980, was based on the premise that conservation was the cheapest form of energy, the most readily available, and the surest way to protect the environment. It set forth a hierarchy for meeting energy demand, with conservation at the top; followed by renewable energy, including wind and solar as well as hydro; with thermal power from oil, gas, or nuclear plants to be used as a last resort. The law also gave BPA new responsibilities for mitigating the effects of the Columbia River dams on fish and wildlife. Finally, it established the Northwest Electric Power Planning and Conservation Council, to forecast demand and plan ways to meet it.

The council (now the Northwest Power and Conservation Council) met for the first time on April 28, 1981. It consisted of two members each from Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana, appointed by the governors of those states. Daniel J. Evans (1925-2024) was elected as chair. Evans, a Republican who had served three terms as Washington's governor, was a highly respected leader with a strong record as an environmentalist. Johnson, also a Republican (at one time head of Northwest Businessmen for Reagan), had reservations about having an outside group develop a plan that BPA would have to execute. Evans later characterized the relationship between the council and BPA as one of "creative tension" (Power, 24). BPA officials had a slightly different take. "The fact is, we had to work out some real serious turf issues with that council," said James J. Jura (b. 1943), assistant administrator during Johnson's tenure and his replacement as administrator in 1986 (Power, 107).

BPA moved quickly to implement the law. In March 1981, it launched a $400-million program to acquire the equivalent of 300 "average megawatts" (a utility-industry term meaning power produced over a year) through home weatherization, water-heater wrapping, and more efficient lighting of streets, businesses, public buildings, and homes. By 2013, energy efficiency programs were saving more than 1,400 megawatts. In comparison, average production at the Columbia Generating Station -- WPPSS Project 2 -- is 1,170 megawatts.

The agency's efforts to promote alternative energies have been more problematic. BPA began distributing power from the world's first commercially viable windfarm (a Department of Energy project, above the Columbia Gorge) in 1982. Other wind producers soon entered the field and likewise were connected to the BPA grid. The results were almost too successful. In the spring of 2011, for example, heavy runoffs combined with the increasing number of wind turbines to produce much more energy than BPA could sell. The agency made the controversial decision to cut off the turbines, without compensating the owners. In the wake of a number of lawsuits and regulatory rulings, BPA agreed to pay wind energy producers to go off line when necessary to keep the supply of electricity from exceeding the demand. It also began helping to fund research into ways to store wind energy, including injecting it in the form of compressed air into underground cavities in Columbia Basin basalt.

Balancing Act

The most challenging aspect of the law has been the mandate to "protect, mitigate, and enhance fish and wildlife" (sec. 839-b). BPA established a Division of Fish and Wildlife, with an initial staff of 25, in 1982. It later became a full-fledged department with about 100 full-time staff in disciplines including fish biology, ecosystem restoration, pollution prevention and abatement, cultural resource protection, and environmental review. BPA also worked with the Power and Conservation Council, Columbia Basin tribes, and other federal, state, and private organizations to develop protocols to repair damage done to fish and wildlife by the dams. And for years, it all seemed to be in vain. "Frankly, the region’s fish recovery program is a mess," BPA Administrator Judi Johansen said in a 1998 speech. "There is little coordination and much waste. What’s worse, we have spent $3 billion already since 1980 with no firm evidence that we are effectively helping the fish" (Power, 191).

Still, there had been a profound shift in the culture at BPA. Paul Raver expressed what was once the agency's guiding principle when he wrote, in 1952, that if "the power of the falling water in our streams" is not used to generate power, "it is wasted beyond recovery" ("Conservation"). Fish now had equal footing with power. New protocols required BPA to curtail hydropower generation when fish were migrating, to ease their passage through the dams. Water budgets, first applied in 1983, dictated the volume of water that had to remain in reservoirs during fall and winter, instead of being used to meet seasonal power demands. The stored water is then released in spring, mimicking natural patterns, helping young ocean-going fish find their way to the sea. Since large volumes of water plunging over spillways can increase the level of dissolved gases in the water, killing fish, flow deflectors were installed at many dams. Spillway weirs and other so-called surface passage systems also helped improve fish survival rates.

BPA reported in 2013 that it had spent more than $13.8 billion on fish and wildlife programs. The sum included the value of revenue that was lost when hydro production was cut to help migrating fish. Fisheries experts were heartened when more than a million Chinook salmon made it past Bonneville Dam that year, the highest total since 1938. "The dams have been overhauled from the inside out to be safer for fish in ways never contemplated when they were constructed," a BPA historian noted. "But litigation and emotion still swirl around the protection of salmon" -- and some people contend that nothing short of breaching the dams will fully restore salmon and steelhead on the Columbia river system (Power, 172).

Humming Along

Drought, flood, too much water, not enough, presidential elections, laws, lawsuits, forces of nature and of man have all played a hand in the Bonneville story. "The new legal unit does not suffer from a lack of business," the Annual Report noted wryly in 1977 (p. 9). The 1992 Energy Policy Act, which deregulated the utility industry, gave independent energy marketers new access to BPA's transmission lines. They plucked off BPA customers by offering lower rates; BPA then had to compete with the marketers for the use of its own grid. By 1995, the agency's financial situation was so bad the Tri-City Herald ran a front-page story with the headline "BPA on Brink of Disaster" (May 21, 1995). BPA cut staff, deferred maintenance on the transmission system, reduced its budget for conservation. The worst was yet to come: an energy crisis that affected the entire West Coast in the early 2000s, brought on by market manipulation by power traders and exacerbated by several consecutive low-water years.

The political buffeting has been as consistent as the winds that blow over the Columbia Gorge. The Carter, Reagan, Bush (the elder), and Clinton administrations all proposed selling BPA. The second President Bush took a different approach, proposing that surplus revenue from BPA be used to pay down the federal debt, instead of lowering electric rates for Northwest consumers and industries. The Northwest Congressional delegation closed ranks to block that move, as it has with other efforts to dismantle or weaken BPA.

Sometimes pilloried, often ignored, BPA "is not, and never has been, a typical utility" (Kramer, 4). It does not own or operate any dams or power plants; it generates no power on its own. Yet every day millions of people depend on the electricity that hums over its 15,000 miles of transmission lines. New challenges await, from climate change to the energy demands of internet servers, but the agency remains at the very center of the economy and the environment of the Pacific Northwest.