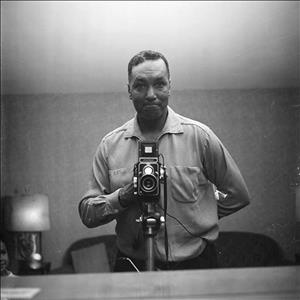

Albert "Al" Smith, Seattle's preeminent African American photographer, was the son of a West Indies immigrant couple who settled in the heart of Seattle's Central Area around 1914. He developed an early interest in photography, experimenting as a mere lad with a simple Kodak Brownie camera. The first African American to attend O'Dea High School, he set out to see the world as a ship steward and while in Japan acquired his first high-quality camera. His life-long hobby documented the Northwest from the Great Depression through World War II, the Civil Rights era, and beyond. Along the way, he married Izzy Donaldson and they raised three happy children. In the 1940s Smith formed his "On the Spot" photography side-business, shooting many thousands of images -- the most renowned of which documented the early Jackson Street jazz scene. In time Smith's work supported exhibits at Seattle's Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI), the Experience Music Project, the Northwest African American Museum, and the Wing Luke Museum. In 2014 the Al Smith collection -- a unique archive covering an otherwise woefully under-represented realm, the daily lives of Seattle's black community in the twentieth century -- was donated to MOHAI.

Deep Roots

Albert Joseph Septimus "Al" Smith was born in Seattle on April 4, 1916, to Claude Percival "Percy" Smith (1882-1944) and his wife Inez Smith (1888-1966), who both originally hailed from the British West Indies island of Jamaica. Early in the twentieth century Percy had moved to England, while Inez had relocated to Victoria, B.C., to live with an aunt. In 1912 Percy set out by ship for America and made his way to Victoria. Eventually, as a couple, the two traveled to Seattle, where they married on December 28, 1914, at St. James Cathedral. Their son Al was born at home -- an apartment above a grocery store at 5th Avenue and Jefferson Street -- and their daughter Vera came along in 1918.

The Smiths' next residence, at 1316 E Madison Street, was one shared with Sarah M. Whitley (d. 1935), an old friend of Inez's aunt who ended up happily fulfilling the role of "acting grandma" to the two Smith kids. Then, when that property was sold, the quintet moved temporarily to a new spot at 919 23rd Avenue, and finally rented another house, at 1414 Jefferson Street, together -- one that the Smith family would retain well into the 1940s. Throughout those early years the Smiths enjoyed the camaraderie of Seattle's small but lively community of fellow West Indian immigrants.

Initially Percy worked at the Seattle Hotel in Pioneer Square, the site of today's "sinking ship " parking garage, and later for the Ideal Dairy Company in the Belltown section of downtown. Meanwhile Inez worked s a domestic, cleaning houses and surprising her clients with her proper "Bostonian" English and vast vocabulary. The two Smith children were both attending the Immaculate Grade School when the Great Depression hit and their father lost his job and of necessity signed on to sail with the Merchant Marine. Whitley soon stepped up and offered to pay the tuition fees for Al to attend O'Dea, the private Catholic all-boys high school, where he blazed a trail as the school's first African American student. Vera, however, was relegated to attend the nearby public school, Broadway High. As the years rolled by, Percy returned home less and less, and eventually drifted away from his family.

Off to Sea

As a young boy Al had shown an interest in photography and at age 12 he was given a Kodak Brownie camera, thus beginning his life-long avocation. A number of his earliest surviving shots are of Seattle's legendary black football team, the Ubangi Blackhawks, and the all-female baseball team the Owls. He also joined -- as the only black member -- a local Boy Scout troop that met at the Plymouth Congregational Church and enjoyed their overnight camping adventures.

He also demonstrated an early interest in travel -- "I liked to hobo and I wanted to see the world" (Giske) -- but when he and a fellow eighth-grade pal lit out jumping freight trains, Sarah Whitley called the police who eventually located the boys in Denver and sent them back home. But that sense of wanderlust wasn't diminished and Smith would eventually work as a Union Pacific train porter and on ocean liners.

First, in the summer of 1935 -- right before what would have been his senior year of high school, where he'd gained notoriety as a guard on O'Dea's 1933 city-championship basketball team -- Smith followed his father's footsteps and sailed away with the Merchant Marine Union, a path that would take him to such locales as China, Japan, and the Philippines. And it was a small world after all, or so it would seem: On one excursion Percy and Al Smith discovered that they were working the same ship, the USS Ruth Alexander, but anti-nepotism rules made it difficult for the two to have much communication or direct contact -- though Percy did once whisper to his son that there was some wine in his locker that he'd gladly share!

Working as a ship steward provided Al Smith with plenty of experiences and opportunities -- including the chance to acquire a superior German-made Ikoflex camera while on his final trip to Japan in 1937. Then around 1938, while motoring slowly down the Yangtze River in China, Smith made eye contact with Percy, who was working aboard another ship that his was passing. He hollered "Hi, Percy," and his father replied "Hi, son" -- the last contact the two would ever have.

Life Goes On

Back in Seattle in 1941 -- and now a member of the "Colored Branch" of the Marine Cooks and Stewards Association -- Smith was helping prepare the USS President Grant for a passenger run to Japan when a shipmate was visited by a girlfriend at the pier. Accompanying her was a friend named Izzy whom Smith had already admired from afar while she was waitressing at Mrs. Smith's Restaurant at 22nd Avenue & E Madison Street. The family of Isabelle "Izzy" Donaldson (1916-2008) had Northwest roots dating back to the 1890s coal-mining days in Roslyn, Kittitas County, where her family first settled after fleeing the Deep South. Izzy herself was a graduate of Seattle's Horace Mann Elementary School and Cleveland High School. Smitten by Smith, she mailed him a letter, which he was surprised to receive later while shipboard.

Upon his return they reconnected and after some courtship the young couple was married on October 26, 1941, at the Immaculate Conception Catholic Church (820 18th Avenue) in Seattle's Central Area -- the church they would attend for the remainder of their days. After working in the stockroom at Zukor's Dress Shop at 3rd Avenue and Pike Street downtown, Smith managed to find a better job at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, while his bride moved up to a gig as hat-check girl downtown at the Italian Club (1413 5th Avenue).

They had a son, Al "Butch" J. Smith Jr. (b. 1942), and around 1946 Smith Sr. moved on to a job with the City of Seattle Engineering Department and then in 1950 began a long career with the U.S. Postal Service. The Smiths bought a home at 125 23rd Avenue in the Central Area. The couple also had a daughter, Cheryl Inez Smith (b. 1952), adopted another, Omenka, in 1953, and along the way developed great circles of long-lasting friends, became consummate house-party hosts, and were stalwart members of their church.

In 1956, as racial discrimination in the real-estate realm eased, the Smith family moved northward into the formerly white neighborhood of North Capitol Hill and bought their dream home, at 1106 25th Avenue E, which overlooked the Washington Park Arboretum, where they settled in for good. Over the years Izzy Smith would serve as a secretary for the Seattle School District and then, until retiring in 1979, as the executive secretary for the vice president of Shoreline Community College. Meanwhile Al Smith remained with the Postal Service until 1974 and then took on a part-time mail-handler gig with Seattle First National Bank until 1996. Along the way Izzy volunteered her time in the juvenile court system, as Al did at the Seattle Senior Citizens Center.

Always Active in Photography

From the start, all the time that he was working full time and, with Izzy, establishing a home and raising their family, Smith maintained an active interest in photography. Indeed, he joined the local Japanese Camera Club as the sole black member.

Al Smith was not the only African American active in photography in Seattle -- others included Odell "The Picture Man" Lee and Charles Johnson. One day Smith met Johnson at the photography counter of Seattle's giant outdoor-gear shop, Warshal's Sporting Goods, at First Avenue and Madison Street, and the two began talking. As a self-taught photographer, Smith realized that Johnson's skills were more advanced than his own and asked if he could get some pointers in the art of photography as well as darkroom developing techniques. Johnson invited Smith to visit his home near Volunteer Park on Capitol Hill, where the informal schooling began.

In time Smith picked up a professional-quality 4x5 Speed Graphic camera and then jury-rigged a makeshift darkroom in his kitchen (After the Smiths bought their first home, he built a real darkroom.). Luckily for posterity, Smith cultivated a habit of taking one of his prized cameras almost everywhere he went. And he went everywhere it seems: to parades and festivals, to circuses and boxing matches, to schools and churches, to weddings and funerals -- and even gory street-crime scenes. Among the big names he captured on film were a young boxer named Joe Louis (1914-1981), the vaudeville clown Emmett Kelly (1898-1979), famed political-science professor Ralph Bunche (1903-1971) of Howard University, future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall (1908-1993), and a visiting President Harry S. Truman (1884-1972).

In the 1940s he began a side business, Al Smith: On the Spot -- a service whereby he would snap photos of patrons, dancers, and entertainers at various local nightclubs and concert theaters, and then, within days, mail them a print or deliver it back to them at the same club the following week. All for 50 cents a shot! "It was fun," Smith recalled, "I made a little money, but mostly I got to spend a little more on my hobby. And I loved the music, the jazz, even though I couldn't keep good time!" (Giske). The business name was a reference to the old term "Johnny-on-the-Spot," once used to describe someone who was always prompt and had the good timing to be where the action was.

On the Spot

Much of the best action in town during the 1940s took place in the scores of black-oriented nightclubs that lined both sides of Jackson Street from the Pioneer Square neighborhood eastward into the Central Area. These were the jazz rooms where musical talents including Ray Charles (1930-2004), Ernestine Anderson (1928-2016), and Quincy Jones (1933-2024) honed their skills before breaking out as international stars. But a lot more than music was taking place there. As Smith once recalled: "It was fascinating: I didn't get to know too many of the local musicians until later, but I was acquainted with the gamblers and policemen right away" (Giske). Another time Smith confessed that during the rationing days of World War II he played a small role in all this nightlife merry-making: "I remember the liquor. You could only get so much ... I remember I used to get the liquor and I sold it down at the clubs" (Smith transcript, 26).

The fact that he was now showing up with that professional-grade Speed Graphic camera gave him instant credibility: "People took me more seriously with the Speed Graphic ... I could cross police lines, get back stage, even walk right out onstage" (Giske). And so he did. Among the estimated 10,000-plus images in his archives are Seattle shots of such big-time touring musicians as Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, Fats Waller, Jimmie Lunceford, Kathryn Dunham, Lionel Hampton, Erskine Hawkins, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Tommy Dorsey, Harry James, Woody Herman, Hazel Scott, Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstein, Paul Robeson, and the Mills Brothers. Smith also captured images of scores of prominent hometown jazzers including pianist Oscar Holden, Leon Vaughan's band, Floyd Franklin's band, the Rizal Club band, sax ace Billy Tolles, bluesman Clarence Williams, guitarist Milt Green, nightclub pianist Merceedees Whelcker, and so many others.

Wide Exposure

Recognition for Smith's skills was sporadic and decidedly late in coming. Some of the earliest came in 1949 when one of his pictures won a Newspaper National Snapshot Award Certificate of Merit and was displayed at the Explorers' Hall of the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C. He went on to win several additional awards in the same competition: an Honorable Mention Award for his "Feeding the Ducks" photo, and Second Place awards for his photos "H.M.S. Bounty" and "Bulldogging a Steer."

In the 1960s Smith attended and photographed civil rights marches and demonstrations, Black Panther rallies, and an appearance by Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) chairman Stokely Carmichael (1941-1998) at Garfield High. By the 1970s Smith was a familiar presence at Seattle Supersonics basketball games, where he served as the unofficial photographer of the 1979 NBA-champion team.

But then the years kept rolling by fast. In the mid-1980s the King County Landmarks and Heritage Commission provided a grant in support of collaboration between Smith and volunteers with the Black Heritage Society of Washington State and Seattle's Museum of History and Industry, who launched a multi-year project that organized and vetted several hundred of his vintage photos. That initial effort led to an exhibit, titled Al Smith's Neighborhood, of 44 images at MOHAI from January through March of 1986. That June a smaller exhibit was mounted at the Douglass-Truth Library in the Central Area, and that same month saw Mayor Charles Royer honoring Smith, along with Fitzgerald Beaver (1922-1991), the longtime publisher of Seattle African American newspaper The Facts, by declaring June 8 to be "Fitzgerald Beaver -- Albert Smith Day."

Smith's Legacy

By then word of the existence of such a historically significant photo archive was starting to spread far and wide. In June 1990 New York's Cort Productions licensed five of Smith's 1940s nightclub photos for inclusion in the documentary Listen Up: The Lives of Quincy Jones. The following year WNET in New York licensed some additional images for use in a televised documentary on Ray Charles. In October 1993 MOHAI debuted a major exhibit, Jazz on the Spot: Photographs by Al Smith. In 1996 the A&E Network licensed some images for the Quincy Jones production Biography: This Week, and in 1997 The Seattle Times featured Smith on the cover of Pacific magazine. In 2000 Seattle's music museum, the Experience Music Project (EMP), opened with an inaugural exhibit about local jazz history that used several of his photographs. In 2010, two years after Al Smith Sr. died at the age of 92 (Izzy Smith, his wife of more than 66 years, died a few months before he did), his estate loaned the new Northwest African American Museum (NAAM) some images for display. In 2012 the estate loaned 10 photos to the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle's Chinatown-International District. And in 2014 the Al Smith Foundation made a final and permanent donation of the photographer's images and gear to MOHAI, which was charged with preserving and protecting the historically priceless materials.

In sum, Smith captured what can be considered the most significant photographic representation of Seattle's African American community of the mid-twentieth century. But beyond his immediate neighborhood, Smith also had a keen curiosity about his whole hometown, its people, and the wide range of their social and cultural activities. Thus his archives also feature gems documenting Seattle's Caucasian, Chinese, and Japanese communities -- a historically unique and visually compelling record of life in Seattle that simply doesn't exist anywhere else. A president of the Black Heritage Society, Dr. Spencer G. Shaw (1917-2010), best summarized the importance of Al Smith and his life's work when he wrote in 1996:

"For nearly sixty years this recognized photographer has utilized his competency and skill to record, visually, people, places and events that relate to the African-American experiences in the Pacific Northwest. Evolving from his work is a massive, irreplaceable collection that is without parallel. ... Serving as a unique example of recapturing history through the lens, film and flashbulb, this collection is tangible evidence of Mr. Smith's ability to use photography, as an art form, to preserve the legacies and contributions of African-Americans to the culture and growth of Washington" (Shaw to Giske).