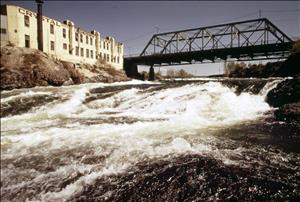

The Washington Water Power Company, now Avista, has been the main power utility for Spokane and much of eastern Washington since its incorporation in 1889. Washington Water Power (WWP) was founded by 10 investors who recognized the hydroelectric potential of the Lower Falls of the Spokane River, which roared right past downtown Spokane. The company built its first power station on the river in 1890 and soon bought out the city's competing electric companies. It also bought up most local streetcar companies and became the city's main provider of public transportation into the 1930s. WWP also operated Natatorium Park, Spokane's landmark amusement park. It built six dams on the Spokane River and later added two on the Clark Fork River in Idaho. During the rise of the public power movement it fought to remain a privately owned utility and ultimately succeeded. In 1999 it changed its name to Avista Corp.

Spokane River Hydroelectricity

Even before the birth of Washington Water Power, hydroelectricity was illuminating hundreds of flickering city lights in Spokane, originally founded (as "Spokane Falls") precisely because it sat next to the roaring falls of the Spokane River. At first crude flumes and waterwheels powered only sawmills and flour mills, not electric generators. However, on September 2, 1885, George A. Fitch installed a small "Brush arc dynamo" -- dismantled from an old steamship -- in the basement of a Spokane flour mill and generated the city's first electricity, enough direct current to illuminate 11 arc lights "in the straggling business district" (Crosby, 7).

By 1886 a group of local businessmen bought Fitch out. They ordered an Edison electric-lighting plant, installed it in the Spokane River near Post Street, and soon lit, among other things, Spokane's first opera performance. The traveling Jeannie Winston Opera Company performed in a tent, and large flying insects hovered around the arc lights and threw distorted shadows that seemed "to swoop upon the actors" (Crosby, 8). The electric company was soon reorganized as the Edison Electric Illuminating Co. of Spokane Falls. By 1888, Spokane's 1,200 electric streetlamps were "second in the Northwest only to Hailey, Idaho" (Blewett, 4). That year, the presses of the Spokane Daily Chronicle were powered for the first time by electricity. A city with its own downtown waterfalls had a clear advantage in the age of electricity.

Still, electric service remained shaky in those early years, according to an official WWP history:

"Candles and oil lamps stood ready for supplemental use ... It wasn't uncommon at the time for sawmill operators to dump huge amounts sawdust in the river, clogging flumes and water wheels. Young boys, apparently fond of fireworks, were known to cause short circuits by throwing pieces of metal across bare wires" ("History").

A group of Spokane businessmen, some involved in the Edison operation, soon recognized that the greatest source of water power -- the crashing Lower Falls of the Spokane River -- remained untapped. They envisioned dams, not just rickety flumes. They attempted to interest Eastern investors, to no avail. Even Thomas Edison (1847-1931) himself then believed that "steam power was preferable to water" (Blewett, 4). So these young Spokane entrepreneurs decided to go their own way.

The Washington Water Power Company

On March 13, 1889, 10 investors signed articles of incorporation for The Washington Water Power Company. They were F. Rockwood Moore (1852-1895), J. W. Chapman, J. P. M. Richards, J. D. Sherwood, W. S. Norman, Daniel Chase Corbin (1832-1918), Cyrus R. Burnes, William Pettet, H. Bolster, and J. Prickett. The articles of incorporation were filed March 15, 1889, in Olympia. The company was strictly a development company for the waterfall power station at this point -- it would not become a true "operating organization" until later (Crosby, 9). Moore and Sherwood were the two largest investors. Moore was typical of the young go-getters in booming Spokane: Starting with a general store, he quickly became a bank president, mining mogul, and organizer of two streetcar lines. Now he was the first president of The Washington Water Power Company.

It was a shaky proposition, at best. The fledgling company was competing with the Edison company and another new water-power company that wanted to develop the Upper Falls. It also faced serious financial questions, according to a report apparently prepared for prospective investors, which stated that only $58,341 of the company's $1 million capitalization had been collected as of April 1, 1889, and that the company already owed $140,000 in payments due. It went on to question WWP's "title claims, its valuation of properties held, the amount of land actually under control" and even, perhaps most startlingly, "the suitability of the site for water power" (Blewett, 7). However, the report writers found some cause for optimism. The company's founders were "among the wealthiest, most enterprising, successful and reliable business men of the City ... as a rule, they are young men, and are credited with having made much money by successful operations in real estate" (Blewett, 7).

They soon needed all the grit they could muster. Work on the company's Lower Falls generator was still in progress when the Great Fire of Spokane began on August 4, 1889, and destroyed the majority of the business district. At first it appeared that WWP's dynamos were in the path of the flames and plans were made to lower them into the river to protect them. This proved unnecessary when the fire's path veered. However, the fire obliterated many of the city's arc lights and outdoor wires. Crews sprang into action, "rustled" wire wherever they could find it, even using baling wire and barbed wire, and strung it up on "any available support -- trees, bridges, odd poles, corners of buildings" (Crosby, 12). By the next evening, downtown street lights came back on "to the amazement of the tired citizens" (Crosby, 12).

A modern city began to rise on the ashes -- and a modern city meant an electric city. Demand grew so rapidly that WWP decided to push ahead with an even bigger development on the Lower Falls -- an 18-foot-high rock-crib dam and powerhouse, soon known at the Monroe Street Power Station. Three smaller generating stations were operating on the river, but completion of the Monroe Street Power Station on November 12, 1890, "meant the beginning of the end for the smaller plants along the river" (Blewett, 8). WWP began buying portions of the Edison Electric Illuminating Co. and "by '91 had obtained a controlling interest" (Blewett, 8). The other dynamos were moved into the Monroe Street Power Station, bringing its capacity to 894 kilowatts, which expanded to 1,439 kilowatts by 1892. Competitors still existed, but WWP's place as Spokane's main power company was now established.

However, it was still not exactly a lucrative proposition, compared to the huge profits to be made in mining and lumber. WWP paid its first stockholder dividend in 1892 -- only 2 percent. Stockholders consoled themselves by regarding "their company as a growing institution, functioning efficiently at its task of furnishing a public service," according to Edward J. Crosby, an early historian of WWP (Crosby, 16).

Streetcar Lines

Streetcar lines provided one avenue of growth. Electricity had recently proven far superior to horses or steam for powering streetcars. Beginning about 1891, WWP began snapping up numerous small streetcar companies in Spokane, including the Spokane Street Railway Company. WWP had plenty of incentives for getting into the business. Streetcar use not only increased electrical demand, but streetcar lines in the pre-automobile era were a primary driver of residential development outside downtown areas, allowing a city to expand, which in turn allowed a power company to expand.

The nationwide Financial Panic of 1893 nearly derailed WWP's plans. The ensuing depression caused a drop in electrical demand and put a severe strain on Spokane's entire banking system. Three local banks failed, including WWP's main source of credit. "Those of us who were here at that time will never forget how black everything seemed to be," wrote John B. Fisken, the electrical engineer who installed the Monroe Street Power Station systems and who later became WWP's chief engineer (Fisken).

In 1895, the company was forced to default on its bonds. William Augustus White, a New York financier and a principal bondholder, chaired a committee to reorganize the company. In 1898, the committee made a startling recommendation: Stockholders would be required to turn in "either 40 percent of their stock or cash in the amount of $10 per share" (Blewett, 9). It was a tough dose of medicine, but it worked. By 1898, the stockholders had advanced enough money "to put the company on a sound financial basis" (Fisken). To complete the reorganization, in 1899 all of WWP's various properties, including the Edison Electric Illuminating Company and the Spokane Street Railway Company, were merged into one company, The Washington Water Power Company, "and the other companies disbanded" (Blewett, 9).

When WWP had acquired the Spokane Street Railway in 1892, it also acquired an amusement park called Twickenham Park, above the banks of the Spokane River. In 1895 WWP added a huge swimming pool and renamed the attraction Natatorium Park. It became the city's premier amusement park, with acres of thrill rides, carousels, gardens, dance halls, athletic fields, and water features. This was another smart business move for a power company that owned streetcar lines. Natatorium Park gave people a reason to ride the streetcars on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. Crowds on summer weekends often exceeded 20,000 at the all-purpose recreation site. Babe Ruth smashed a home run on its baseball diamond and Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington pounded out jazz on its bandstand.

By 1900 WWP "had almost cornered the market on public transportation in Spokane" (Blewett, 12). As the new century began, WWP was seeking other ways to expand. In 1901 it built its first transmission line outside of Spokane, to the neighboring railyard town of Hillyard. Around the same time, a group of mine owners in the lucrative Coeur d'Alene mining district bought the power site at Post Falls, Idaho, where the Spokane River emerges from Lake Coeur d'Alene. WWP, which also had designs on that site, negotiated a deal with the mine owners to purchase it and deliver electricity to the mines. It was a massive undertaking, requiring a 100-mile transmission line to Burke, Idaho -- "the longest high voltage line in the world at the time" (Blewett, 11).

General manager D. L. Huntington (1871-1929) had the blueprints analyzed by Charles Proteus Steinmetz (1865-1923), an Edison associate who formulated the theory of alternating current. Steinmetz gave his approval and the line was completed in 1903, carrying 45,000 volts to Burke, later increased to become only "the second line in the civilized world to be built for operation at 60,000 volts" (Fisken.) WWP soon built many other far-flung transmission lines -- south to Colfax and Moscow; west to Odessa and Coulee City; north to Newport and Sandpoint, Idaho -- greatly expanding the company's reach. In Spokane, famed architect Kirtland Cutter (1860-1939) designed the Post Street Substation, built in 1909 and still a Spokane riverfront landmark in the twenty-first century.

Building Dams

In fact, WWP's load (electrical demand) was "growing so rapidly that it was impossible to develop hydraulic power fast enough ... so a steam plant was built in 1907 at Ross Park," which "served a useful purpose" until 1916 when it was abandoned (Fisken). By that time, hydroelectric power was pouring into WWP's system from several big new Spokane River dams the company built. The first was the Post Falls dam, completed in 1906 with three generators (two were added in 1907 and 1908) with an installed capacity of 15,000 watts.

The Little Falls Dam on the Spokane River north of Reardan was completed in 1910 and extended in 1911. It had an installed capacity of 32,000 kilowatts, which "increased WWP's system capacity by almost 50 percent" (Blewett, 22). The Long Lake Dam, just a few miles upstream, was even more massive -- its 170-foot-high spillways were the highest in the world when it was completed in 1915. It had an installed capacity of 70,000 kilowatts, which is why the Ross Park steam plant was no longer needed. The Long Lake and Little Falls dams also put an end to salmon harvesting at the confluence of the Spokane and Little Spokane rivers. Tribes from all over the Inland Northwest had gathered there for millennia, but runs were now blocked permanently by those dams (Grand Coulee Dam would eventually put an end to all salmon runs on the remainder of the Spokane River).

WWP's building boom continued in 1922 with the addition of the Upper Falls Dam, not far from the spot where George Fitch installed that original primitive dynamo on the Spokane River. The Upper Falls Dam had an installed capacity of 10,000 kilowatts. In 1925 WWP acquired another Spokane River dam, the Nine Mile Dam, built about nine miles downstream from Spokane by the Spokane & Eastern Railway in 1908 to supply power to its electric railway system. It had an installed capacity of 12,000 kilowatts. In 1927 WWP ventured far from its home territory and built the Chelan Dam on the Chelan River in the Cascade Range, with an installed capacity of 48,000 kilowatts. (The Chelan County Public Utility District purchased this dam from WWP in 1955). Meanwhile, WWP was continually adding generators to its existing sites. In fact, the company added generating capacity nearly constantly from 1903 and 1930.

Building Demand

WWP was also building demand for all this new, relatively inexpensive electricity. Beginning in the 1910s, it aggressively marketed electric ranges and water heaters -- still relative novelties in many parts of the nation. One of its own employees, Lloyd Copeman, had identified one of the flaws of electric ranges -- their controls were inefficient and inaccurate. So Copeman developed and later patented an automatic thermostat control for an electric range that "revolutionized home cooking across the country" (125 Years ..., 8).

The company's dividends were also expanding. From 1922 through 1930, shareholders earned a healthy 8 percent every year. The company's corporate structure also went through a change. In 1928 WWP was acquired by the American Power & Light Co., a subsidiary of the Electric Bond and Share Co. (EBASCO), a large national utility holding company created by General Electric. Meanwhile, WWP's power lines were now reaching a vast area of eastern and central Washington. By 1930 WWP had purchased dozens of rural and small-town electric distribution companies. A map from that year shows WWP power lines stretching west to Chelan and Methow, south to Grangeville, Idaho, east to Burke, Idaho, and north to the Canadian border. "In little more than 40 years, WWP had grown from a dream with no facilities, into a system covering thousands of miles in two states, bringing the first service to many people, including many rural customers," according to WWP historian Steve Blewett (Blewett, 25). Crosby wrote in 1930 that the company "views with some pride its record in those years -- the fact that the electric service it has been privileged to provide during all that time has been the equal of that anywhere in the world" (Crosby, 22).

Yet challenges abounded in the 1930s. First, the streetcar business was in bad shape and growing worse, mainly because of the rise of the automobile. In fact, WWP's streetcar ridership had peaked back in 1910 at more than 24 million passengers and then went into a slow and inexorable decline. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that a competing streetcar line, the Spokane Traction Co., had sprung up in 1902 and split the market. The situation became so bad in 1922 that the two lines were forced to merge and became Spokane United Railways, with WWP the primary owner. The company sold Natatorium Park in 1929. The decline continued and the final streetcar rolled through Spokane in 1936, ending WWP's foray into public transportation.

Private or Public Power?

The most serious challenge came in the political arena. Public power companies, like Seattle City Light and Tacoma City Light, had long coexisted in an uneasy relationship with private power companies (also known as investor-owned utilities), such as WWP. Public-power proponents believed that power, as an important public service, should be owned by the public. Private-power proponents argued that private utilities had largely created the nation's enviable electrical grid and were more capable and efficient. However, when the Great Depression hit its nadir in 1933 a number of private utility holding companies failed. WWP's holding companies, American Power & Light and EBASCO, fared better than most, yet there were renewed calls for the the federal government to dissolve the holding companies, take over private power companies and organize public utility districts (PUDs).

The federal Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 "placed the future of EBASCO, AP&L and WWP in limbo" (Blewett, 35). In Senate hearings WWP president Frank T. Post testified that his company had benefited from the "support and guidance of holding companies" and that the act would be better titled "A bill to paralyze and destroy the privately owned electric companies" (Blewett, 36). The act passed, yet it did not destroy WWP. Nearly two decades of court battles ensued before the breakup of the holding companies, and by then WWP had already shed itself of holding companies. Meanwhile, in 1940, the private-power industry recognized WWP with its most prestigious award, the Charles A. Coffin Award, in part for leading the fight against public utility districts. WWP won two more Coffin Awards, in 1950 and 1956.

When World War II arrived, WWP joined with nine other utilities and the Bonneville Power Administration in forming the Northwest Power Pool. WWP interconnected with all the major power utilities in the Northwest to more efficiently deliver power to the region's big aluminum plants, airplane factories and shipyards, which were crucial to the U.S. war effort. When the war ended, WWP and the other utilities recognized the advantages of a regional power pool -- mainly increased efficiency and reliability -- and they chose to keep the Northwest Power Pool intact. The company remained a key member of the Northwest Power Pool as of 2016.

The struggle against public power continued through the 1940s and approached a crisis -- at least for WWP -- beginning in 1949. American Power & Light, having come to believe that WWP was hopelessly "encircled by public power enemies," proposed to sell it to the public utility districts (Blewett, 43). WWP fought hard against this proposal and court battles ensued. In 1952 WWP was victorious and finally, after decades of "financial direction from New York," separated itself from American Power & Light and became "free at last" (Blewett, 43). WWP joined the New York Stock Exchange as a publicly traded investor-owned company on September 25, 1952. Future battles would be fought over encroaching public utility districts, yet the continued existence of WWP as an investor-owned utility was never again in serious doubt.

New Energy Sources

Meanwhile, the growing Northwest was demanding more power. In 1952 and 1953, WWP built the massive Cabinet Gorge Dam on the Clark Fork River in Idaho, with an installed capacity of 200,000 kilowatts, nearly doubling its generating capacity. A dam at nearby Noxon Rapids followed in 1959.

In the 1960s, WWP began exploring other energy sources. It went into partnership in coal fields and natural-gas sites, and became a partner in the nuclear projects being developed by the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS). The nuclear projects stalled, but natural gas grew to become an ever-increasing component of WWP's business. WWP acquired the facilities of Spokane Natural Gas through a 1958 merger. That year, WWP moved into its new headquarters, a landmark midcentury-modern block of steel and glass set on 28 acres at Upriver Drive and Mission Avenue in Spokane. In an atmosphere of increasing cooperation with federal agencies and the state's public utility districts, WWP contracted in the 1960s and 1970s to purchase a portion of the power from new PUD-built dams on the Columbia River, including Priest Rapids, Wanapum, Rocky Reach, Rock Island, and Wells.

The national energy crisis in the 1970s put a strain on WWP's system and drove up prices of both electricity and natural gas. "From 1970 to 1985, rates would increase almost fivefold," yet still be "among the lowest in the nation" because of relatively inexpensive hydropower (Blewett, 54). In 1983, the company built a wood-waste-fired generating project near Kettle Falls and later partnered in the massive coal-fired Colstrip 3 & 4 projects in Montana.

In the 1980s WWP was one of many Northwest utilities battered by the WPPSS bond-default crisis, yet WWP president Wendell J. Satre (1918-2010) was able to negotiate a settlement that limited the company's costs. As in its earliest days, the company's interests were directly tied to the economic progress of the region, so WWP became a leader in a community-development movement that brought new industry and jobs to Spokane. In 1989 the company celebrated its 100th anniversary.

In the 1990s, WWP expanded its service area in eastern Oregon and north Idaho and by the mid-1990s the company was serving more than half a million electric and gas customers. It weathered two natural disasters, the 1991 Firestorm, which destroyed 100 homes in the region, and the 1996 Ice Storm, which cut power to more than 100,000 customers. The ice storm was "the biggest operational challenge" in the company's history to date, with "damage ... so extensive that much of the system had to be rebuilt from the ground up" (125 Years ..., 20-21).

Avista

That decade the company developed several subsidiaries, including WWP Energy Solutions, WWP Fiber, and WWP Energy Resources, with a focus on "energy marketing and asset optimization" (125 Years ..., 16). The company had evolved "from a regional utility to a diversified energy business," and had, its officials believed, outgrown the name Washington Water Power (125 Years ..., 17). On January 1, 1999, all company operations were unified under a new name: Avista Corp. WWP and its WP Natural Gas Division became Avista Utilities, or just Avista for short. The company admitted that "the new name took some getting used to," and The Spokesman-Review made fun of it mercilessly, saying that "it sounds like a bad Dean Martin hit" (Kershner). Yet the name Avista took hold and before long the only remaining vestige of the old name could be found in lights atop the iconic 1909 Post Street Substation.

The Western Energy Crisis of 2000-2001 hit Avista hard, especially since the company experienced record-low water flows in 2001. The company partnered in a natural-gas facility in Oregon that went into operation in 2003. Yet volatile market conditions hurt Avista financially and "at one point, Avista Corp.'s credit rating was reduced to junk status, and the company came within days of not meeting payroll" (125 Years ..., 31). The credit rating rebounded by 2009 to "investment grade" (125 Years ..., 31).

As of 2016, the company had moved into wind power by contracting with the Palouse Wind Project in Whitman County. It had also renewed the licenses on its major Spokane River dams and partnered with the Coeur d'Alene Tribe and Spokane Tribe on restoration and conservation measures. In November 2015, Avista suffered the worst disaster in its history when a windstorm knocked out power to 180,000 customers leaving some in Spokane without power for 10 days.

In the company's 127th year, Avista owned and operated eight hydroelectric facilities and seven thermal generating facilities. It served about 367,000 retail electric customers and 326,000 natural-gas customers in eastern Washington, northern Idaho, and southern and eastern Oregon. It had a total generating capacity of 1,844 megawatts. About 35 percent its power supply came from natural gas, 9 percent from coal, and 6 percent from wind. Nearly half of its electricity still came from water power, fitting for a company that began in 1889 as The Washington Water Power Company.