Architect John Graham Sr. designed many of Seattle’s most significant commercial buildings during the first half of the twentieth century. Many, including the former Frederick & Nelson building (now Nordstrom), still form the core of the city’s commercial district.

Liverpudlian

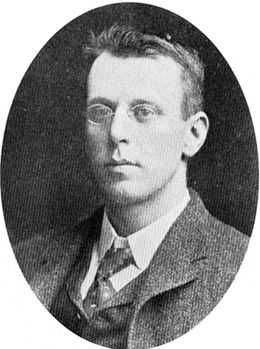

Born in 1873 in Liverpool, England, Graham learned the practice of architecture as an apprentice. In 1901 he moved to Seattle, where he began his prolific career. His professional life began with a few partnerships. His association with David J. Myers (1872-1936) yielded many works including three apartment buildings, the Kenney Presbyterian Home, and a few large-scale houses. Graham designed these with the help of Myers’s prolific firm, Schack, Young & Myers. Graham’s partnership with Myers also produced a number of buildings for the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, including the Agriculture Building.

In 1910, Graham broke away from partnerships. In this year, he began designing a series of Model T assembly plants for the Ford Motor Company, still in its infancy. From 1914 to 1918, he served as Ford’s supervising architect. He designed Ford manufacturing buildings throughout the country including a local plant, located in Seattle’s industrial Cascade district. This brick, steel-frame building illustrates Graham’s nationwide work. The 1913 plant provides substantial interior light through its extensive windows. These windows form the primary exterior walls of the plant. Brick covers structural elements only; the building is quintessentially functional.

Although Graham is best known for his large-scale buildings, he completed a variety of commissions. These varied in style and include:

- The Pierre P. Ferry house (1903-1905, 1905-1906 with Alfred Bodley), located at 1531 10th Avenue E;

- The Plymouth Congregational Church (1910-1912; destroyed);

- The Seattle Yacht Club (1919-1921, located at 1807 East Hamlin Street;

- Physics Hall, University of Washington (1927-1928; altered).

In 1916, Graham began a series of large scale Seattle department store buildings. His downtown Frederick & Nelson Building (1916-1919, now altered, in 2004 owned by Nordstrom) uses generous amounts of glass, much like his Ford factory plant. Windows make up a substantial portion of the exterior walls. White terra cotta covers the structural beams dividing the five-story building. The building has a number of distinctive classical details, reminiscent of ancient Greek and Roman designs. Classical cartouches (decorative oval frames) articulate the dividing beams at the uppermost story. The cornice (the projecting edge of the roof) was one of its most prominent classical features. This was removed during the store’s upward expansion. Modillions (decorative classical brackets) and terra cotta dentils (small, rectangular, tooth-like elements, which often appear beneath modillions) were part of the classical cornice.

The Frederick & Nelson Building, and the Dexter Horton Building (1921-1924), also downtown, effectively and harmoniously combine function with classical style. Instead of presenting “typical” examples of styles, Graham’s 1910 to 1930 designs tended to be well proportioned and functional examples of department stores, office buildings, or assembly plants. The Joshua Green Building (1913), at 4th Avenue and Pike Street is one of his typical steel-frame, terra-cotta-clad structures. The concept of “form following function,” made popular by the influential Chicago architect Louis Sullivan (1856-1924), was to some extent a natural outgrowth of iron- and steel-frame commercial buildings. Graham worked with a self-supporting metal frame and applied the exterior style to this frame.

Graham handled many styles deftly. Graham’s streamlined, dramatic art deco designs are some of the most prominent buildings in downtown Seattle. (Art deco, a style that became popular in the 1920s and 1930s, is characterized by strong abstract patterns and vibrant colors.) The massive, towering Exchange Building (1929-1930) lunges upward in contrast to the relatively flat, horizontal Bon Marche Building (1928-1929), which employs some deco elements. Graham participated in the design of Seattle’s imposing art deco U. S. Marine Hospital (1930-1932), a building generally attributed to the firm of Bebb & Gould. In 1939, Graham executed Seattle’s streamlined Coca-Cola Bottling Plant.

From 1942 until 1946, Graham nurtured his son’s architectural career, providing architect John Graham Jr. with increasing responsibility. In 1946, his son took over the family business; the younger architect became one of Seattle’s most successful commercial architects of the mid-twentieth century.