Edward C. Kilbourne, a Seattle dentist, was the visionary developer of Seattle's Fremont neighborhood, and a leading promoter of electric power utilities in Seattle. In order to bring interested potential homeowners to Fremont, he built an electric trolley to run from Seattle to Lake Union. After Seattle's Great Fire of 1889, Kilbourne received the city's franchise to restore electric power. In 1892, he became majority owner of the future Union Electric Company. Twelve years later he formed Kilbourne & Clark Company to deal electrical machinery and supplies. He ended his long life as a philanthropist.

A Dentist Goes West

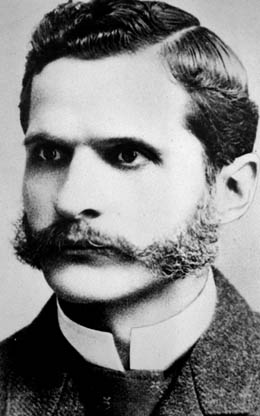

Edward Corliss Kilbourne was born in Vermont on January 12, 1856, and grew up in Aurora, Illinois. Following graduation from high school he studied dentistry under his father, a noted dentist and pioneer of organized dentistry. He practiced with his father until 1880 when poor health sent him west to the mines of Colorado and their outdoor labors. Renewed health, restlessness, and a letter from his uncle, Corliss P. Stone, Seattle mayor in 1872, stating that "The climate of Puget Sound is so invigorating that little boys don't stub their toes," sent him packing to Seattle in 1883.

Like his father, Kilbourne became an excellent clinician. He located his office on Front Street (later 1st Avenue) at James Street, and his practice among Seattle's 10,000 people quickly flourished. He organized the first territorial dental society in 1886 and a year later helped secure passage of the first law regulating the practice of dentistry in the territory. Kilbourne's dental riches and growing political savvy enabled him to invest in real estate beyond the city limits, real estate which he envisioned would absorb the overflow of Seattle's expanding population. He purchased 40 acres from his uncle Corliss on the Union Lake's north shore, just east of present-day Gas Works Park, and platted Kilbourne's Division of the Lake Union Addition.

More Trees Than People

At that time land north of Lake Union was so sparsely settled that to get a toe hold on the lake's north shore first required several swings of the ax. The plat sat at the end of a small steamer route across the lake, which Kilbourne purchased from David Denny (1832-1903). Lots sold quickly, bringing capital for additional investment. In 1888, Kilbourne formed a silent partnership with businessman L. H. Griffith to promote the 240-acre Denny & Hoyt tract at the northwest corner of Lake Union, later to become the town of Fremont, and ultimately the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle. It was a more ambitious project than Kilbourne's first venture, and the 12-passenger steamer Maud Foster proved inadequate for the purpose of bringing people to this new community. Thus, the investors turned to the electric trolley as a more efficient means of transporting potential buyers and new residents to and from Seattle.

Electric Power v. Horse Power

In 1884, Seattle's 5 mph horse-drawn street railway ran to the foot of Queen Anne Hill, with a branch extending from Pike Street out through the woods to Lake Union. But in 1886, electrification with trollers and overhead wires began to replace slow, dangerous, and odiferous animal power. When hilly Richmond, Virginia, installed a successful system the next year, Kilbourne's co-investor, Frank Osgood, traveled east to study electrical power as the new motive force. Upon his return, the associates organized West Street & Lake Union Electric Railway. Within a year the first electric car would roll the rails through the wilderness of Fremont into a new era of suburbanization northward from Seattle.

Real estate developer W. D. Wood (1858-1917) eagerly anticipated this new line, having recently purchased 600 acres of raw land just north of Fremont at Green Lake. Like Kilbourne, he saw efficient, inexpensive transportation as essential in bringing potential buyers to his platted tracts. Kilbourne himself had seen the growth potential of the Green Lake area and in 1889 platted 80 acres known as Kilbourne's Division of Green Lake Addition on the east side. In 1891, Griffith and Kilbourne went into partnership with Wood to electrify 4.5 miles of a previously constructed logging railroad hugging Green Lake's eastern shoreline.

The Home of the Future

In 1886, Kilbourne married Leilla A. Shorey, daughter of early territorial pioneers. They established residence at Green Lake in 1890, moving to a new Victorian cottage overlooking Green Lake near present-day (1999) N 63rd Street. Now steeped in the new technology, Kilbourne had all the rooms built on one floor and installed an electric pump in the attic to draw water from his well. The Kilbournes heated their home with a half dozen small, innovative electric heaters, drawing power from the overhead wires of the nearby trolley line.

Kilbourne's involvement with electrical power persisted into the new century. Following the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, which destroyed the downtown business district and its electric lighting plant, he received the franchise from the city to restore power and bring light to darkened windows. In 1892, he became majority owner of the future Union Electric Company, which held a contract not only for lighting the city with arc and incandescent lights, but also for furnishing power to the public. Twelve years later he formed Kilbourne & Clark Company to deal electrical machinery and supplies, an interest held until 1910 when he retired from active business.

Kilbourne's presence in the Green Lake neighborhood ended with sale of the couples' cottage in 1901. Following retirement, Kilbourne began a third career as philanthropist, focusing much of his time and money on the YMCA and the Plymouth Congregational Church. He also helped secure numerous parks for the city, including Lincoln Park, Kinnear, Woodland, and Ravenna. Throughout the rest of his life he would serve on the boards of many business and volunteer organizations. He died on August 15, 1959, at the age of 103. He left no heirs.