On April 28, 1968, nearly 3,000 spectators flock to Larry Van Over's farm in Duvall to see (hear?) a piano drop from a helicopter. Duvall is located in King County northeast of Seattle.

Van Over, better known as "Jug" for his musicianship as a member of the Willowdale Handcar jug band, had recently heard a recording on KRAB-FM of a piano being destroyed by sledge hammers. Finding the aural experience disappointing led to the speculation (most likely fueled by certain psychoactive chemicals) about dropping a piano from a building, or better yet, a helicopter, and what that drop might sound like.

Van Over enlisted the aid of Paul Dorpat (b. 1938) at Helix. A benefit "Media Mash," co-sponsored by KRAB and Helix, had already been scheduled for April 21, with performances by Country Joe and the Fish among others. The Piano Drop was hooked on as a free premium the following Sunday.

Larry tracked down an old upright piano, moved it to his farm, and contracted a helicopter service out of Boeing Field. The pilot didn't quite get the point, but he had moved pianos with his helicopter before. Having successfully not dropped pianos, he saw no special problem in doing the opposite. As Larry later recalled, "There were a number of Newton's laws that the pilot neglected to consider."

Assured of the feasibility of musical strategic bombing, Larry calmly dropped acid on Sunday afternoon and climbed into the helicopter to guide the pilot out to his farm in Duvall. It was sunny and clear. As the helicopter passed Woodinville, Larry and the pilot noticed that the traffic below was getting heavier and heavier. "Gee, there are a lot of people out today," Larry commented over the engine's roar.

By the turnoff to Larry's farm, he and the pilot realized that they had not been observing mere Sunday drivers. The roads around the farm were a parking lot - and then they saw a wall-to-wall carpet of humanity covering the drop zone. Instead of the 300 participants he expected, the pilot estimated at least 10 times as many people filled the countryside below. At that moment, Larry got that special, tinny taste in his mouth indicating that his mental altimeter had exceeded the helicopter's.

"No way, no way, no way," the pilot muttered with mounting conviction as he set the helicopter down next to the awaiting piano. "What exactly is your apprehension here?" Larry asked innocently.

"They're not going to get out of the way," the pilot explained.

"They'll move, man, they'll move," Larry pleaded with that persuasive power only true evangelists and zonked-out lunatics can muster. "Trust me, man, it'll be like the Red Sea all over again!"

For whatever reason -- curiosity, fear of not getting paid, or a contact high -- the pilot relented. "Okay, but they gotta give me plenty of room, or no drop."

The pilot hitched the piano to a special harness and lifted off. He approached the target, a platform of logs, from an altitude of at least 150 feet. The machine hove into view and the crowd, as Larry had predicted, parted and retreated to a respectful distance.

The pilot brought his machine to a halt mid-air, but bodies in motion tend to remain in motion, and the 500-pound piano dragged the helicopter forward. The pilot panicked and hit the harness release, but nothing happened. He then hit the emergency cable release, and the piano snapped free.

It described a lazy arc through the bright spring sky, overshot the target by several yards, struck the soft earth, and imploded with a singularly unmusical whump. "A piano flop," Paul Dorpat later dubbed it.

The crowd was not disappointed and let loose a collective "Far out!" as it surged toward the remains of the piano. By the time Larry pushed his way to the piano's impact crater, not a stick, wire, ivory, or scrap of felt remained. "They devoured it," he recalled. The last he saw of the instrument was its steel harp being loaded into a VW microbus by two hippies.

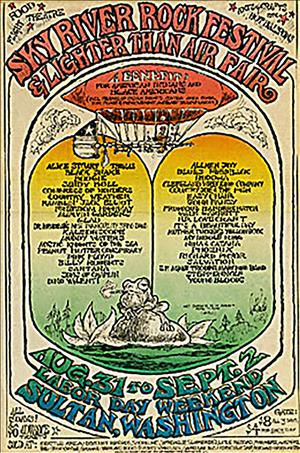

As Country Joe and the Fish fired up their amplifiers, somebody said, "Hey, let's do that again," and so was born the idea for the Sky River Rock Festival and Lighter Than Air Fair, which took place later that year.