Along with every other major West Coast port, Seattle's harbor was paralyzed from May 9 to July 31, 1934, by one of the most important and bitter labor strikes of the twentieth century. The struggle pitted the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA, reorganized as the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union, ILWU, in 1937) against steamship owners, police, and hostile public officials. It also embroiled ILA leader Harry Bridges (1901-1990) and Teamsters Union head Dave Beck (1894-1993) in a long battle for control of the nation's waterfronts. Coastal confrontations with police cost seven strikers their lives, including Seattle ILA leader Shelvy Daffron. King County Sheriff's Special Deputy Steve S. Watson was also killed in a downtown Seattle melee. The worst violence occurred in San Francisco on July 5, 1934, now memorialized as "Bloody Thursday." President Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945) and the National Labor Board (forerunner of the National Labor Relations Board) arbitrated an end to the strike, which firmly established the rights of waterfront workers nationwide.

On the Waterfront

Seattle longshore (from "along shore") workers formed the Stevedores, Longshoremen and Riggers Union of Seattle on June 12, 1886, to improve their workplace conditions and pay. The early organization was weak and mostly conducted wildcat (impromptu) strikes. A month before, employers had established the Pacific Coast Ship Owners' Association for mutual protection against "existing and prospective demands" from the Seamen's Union. In 1916, longshore workers conducted a strike that lasted three months. Some of their demands were met but most gains were lost within a year, chiefly because of the lack of a comprehensive multi-harbor organization that could prevent shippers from playing one port's workers against another's.

A New Deal

Beginning in the late 1920s, after decades of failed strikes (including participation in the Seattle General Strike of 1919), longshore workers in ports from Bellingham to San Diego began to reorganize under one umbrella, the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA). They joined under the terms of President Franklin Roosevelt's National Industrial Recovery Act (NRA), which in 1934 accorded the first federal protection of workers' rights to join unions of their choice and to bargain collectively. (Although the NRA was later declared unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court, organization and bargaining rights were almost immediately (1935) reaffirmed by enactment of the National Labor Relations Act, known as the "Wagner Act." One of the reasons for the action was that workers like the longshore workers were making organizing and bargaining code in the street.)

When employers refused to bargain with the ILA, the men struck to demand a coast-wide contract, with wage and hour improvements and an end to unfair labor practices such as "the speed-up" (when workers are driven to work harder without commensurate pay) and "the shape-up" (when employers hand-picked who would work each day). A key demand was the establishment of hiring halls run by unions, not bosses. Frustrated longshoremen "hung up their hooks" on May 9, 1934. ILA members and allied maritime unions concentrated on stopping trains serving the Seattle waterfront and blocking the use of strike-breaking "scabs" on the docks. On June 9, the Seattle unions agreed to service ships carrying vital supplies to and from Alaska.

Push Comes to Shove

In mid-June, a tentative settlement was offered to ILA and other union members for ratification. As the proposal was debated, newly installed Seattle Mayor Charles L. Smith decreed a "state of emergency" on June 14 and mobilized police "to open" the port, leading to a standoff with picketers the following day. On June 16, all but the ILA's Los Angeles local union rejected the terms of the draft settlement.

Confrontations turned uglier as Seattle strikers battled police and strikebreakers, even on one occasion disarming them. Mayor Smith vowed to intervene on June 20, 1934, and the Seattle Post Intelligencer headlined that "POLICE WILL OPEN PORT TODAY!" Police Chief George Howard focused his forces on Piers 40 and 41 (now [1999] Port of Seattle piers 90-91) and told his men, "This is not our fight. We're here to protect property and prevent the loss of life." He added, "See that your guns are in good shape, but use them only as the last extremity... ."

The city and county massed an army of 300 city police, 200 "special deputies," and 60 state troopers (unlike his counterparts in Oregon and California, Gov. Clarence Martin refused to mobilize the National Guard). They were met at Piers 40-41 by 600 unarmed picketers. Offshore, 18 ships waited to land their cargo, while a squad of scabs (strikebreakers) huddled aboard an old steamer at the end of the dock. Strikers halted a Great Northern train en route to the piers and mounted police charged with clubs and teargas. The workers stood their ground and carried the day.

Outraged by Mayor Smith's perceived betrayal of a promise of "neutrality" in the dispute, Seattle ILA members reinstated the embargo on Alaska cargo. They were not able to maintain their lock on the entire port, however, and cargo began to move in fits and starts. The ILA urged the Labor Council to call a "general strike" to shut down all of Seattle's union workforce, but the Teamsters and other conservative labor leaders defeated the proposal. Although Teamster leader Dave Beck urged Seattle longshoremen to break ranks and negotiate "their own best deal" with Seattle shippers, the local ILA maintained its coastal solidarity.

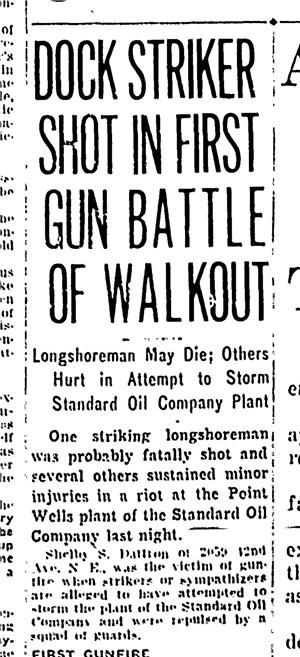

The battle moved inland on June 25 as strikers tussled with police and special deputies near the Smith Tower. The worst confrontation came on the evening of June 30 at the Standard Oil storage tank farm on Point Wells, in present-day Richmond Beach north of Seattle. Striking workers rushed to the area to prevent scabs from servicing tankers. They were met by armed guards at the fence, and one of the latter was heard to shout, "Let's give it to them." Gun shots rang out and strike leader Shelvy Daffron fell mortally wounded. He died the following day. A Snohomish County inquest jury was later unable to fix blame.

Bloody Thursday, July 5, 1934

The violence escalated in San Francisco, leading to a riot on July 3. Two days later, on "Bloody Thursday," two strikers were shot dead and many wounded when police cleared the Embarcadero area by force. On July 6 in Seattle, more than 6,000 maritime workers turned out for Shelvy Daffron's funeral at the downtown Eagles Hall. Three days later, tens of thousands of workers marched in San Francisco, and public opinion began to shift to their side. On the night of July 9, the strike claimed a second victim in Seattle. Strikers confronted a carload of special deputies at the corner of 3rd Avenue and Seneca Street and rolled their vehicle over. One of the deputies, Steve S. Watson, was fatally shot with his own gun during the struggle. An inquest jury was again unable to name a suspect.

The press, however, blamed "Reds" for inciting violence. The drumbeat of publicity against labor "radicals" intensified as San Francisco workers declared their intent to call a general strike on July 16. This was averted when both employers and the ILA tentatively agreed to submit to arbitration by a special panel appointed by President Roosevelt. The agreement did not prevent further confrontations. Police again battled strikers at Smith Cove on July 18, and arrested five "Communists." Chief Howard resigned the next day in an unspecified dispute with Mayor Smith over handling the strike. Seattle Police arrested 110 more "Communist agitators" over the next two days and raided the Communist Party's local headquarters. Of greater threat to the strike, Teamsters started to break ranks and return to work all along the Coast, which led to long-lasting resentments.

Union Triumph

Union members voted on the arbitration proposal on July 23, while headlines blared news that on the previous night in Chicago bank robber John Dillinger had been gunned down. The affirmative vote was reported on July 24 (only the Everett ILA local voted against it), but the deal almost unraveled when employers tried to retake control of hiring halls.

This move was rebuffed and strikers all along the Coast went back to work on July 31. The ILA won virtually all of its demands with the final settlement in October. The arbitration panel "award" established that "hiring of all longshoremen shall be through halls maintained and operated jointly" but "the dispatcher shall be selected by the International Longshoremen's Association." This was a major victory. (The Tacoma local was exempted from this provision because that hall remained under full union control, setting the standard for the rest of the industry.)

The award also granted wage increases to 95 cents an hour (the workers had wanted $1 an hour raise) for straight time and $1.50 for overtime, a shorter week of 30 hours, and a six hour day. Finally, the West Coast longshore workers gained recognition coast-wide, from Bellingham to San Diego, as members of a single unified organization.

The union had survived an 83-day strike after lying dormant for 14 years. The event handed Dave Beck's Teamsters a rare setback while cementing the leadership of Harry Bridges, a young Australian immigrant "wharfie" in San Francisco who chaired the West Coast Joint Strike Committee and led the ILWU from 1937 until his retirement 30 years later. In the words of Gerry Bulcke, a veteran of the 1934 strike, "We had a new sense of our worth, of our power as workers."