On January 19, 1900, William J. Grambs (1862-1943), acting on behalf of Boston-based utilities conglomerate Stone & Webster, incorporates the Seattle Electric Company, a pivotal step in a fast-paced effort to gain control of Seattle's myriad electrical-generation plants and street railways. Grambs concentrates on gathering together the steam plants that produce most of the city's electricity, while banker Jacob Furth (1840-1914) and businessman James D. Lowman (1856-1947) represent Stone & Webster in consolidating Seattle's numerous electric-streetcar companies. By 1903, the conglomerate has successfully united almost all the city's streetcar lines and steam-generation plants under the ownership of the Seattle Electric Company.

The Beginnings

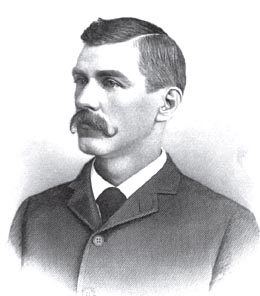

Sidney Z. Mitchell (1862-1944) was just 24 years old when he was sent west by Thomas Edison's (1847-1931) Electric Light Company in 1885 to introduce incandescent lighting to the Northwest. By November of that year Mitchell and another Edison representative, F. H. Sparling, had won a 25-year franchise from the city council "granting the right to erect poles and stretch wires thereon for electric purposes" (Ordinance No. 693). Their Seattle Electric Lighting Company built a small, steam-powered dynamo plant on Jackson Street that when fired up on March 22, 1886, was the first and only central-station system for electric lighting west of the Rocky Mountains.

The company's position as first was forever secure, but its reign as the only such plant was very brief. Less than three months later, on June 5, 1886, a similar city franchise was granted to the Seattle Gas & Electric Light Company, owned in large part by three prominent Seattle men: banker Dexter Horton (1825-1904); pioneer Arthur Denny (1822-1899); and a former mayor, John Collins (1835-1903). They built the city's second steam-generation plant, at 4th Avenue S and Main Street. Between then and the beginning of the twentieth century many more small steam plants generating electricity cropped up around Seattle and outlying areas. Some were dedicated to powering electric-streetcar lines, some provided electricity solely for lighting, several did both.

This profusion had its roots in both financial speculation and the laws of physics. Washington was not even a state until 1889, and Seattle remained very much a frontier town, full of men (and a few women) competing to make their fortunes in a city that was really starting to boom. Electricity and urban transportation seemed very promising areas for investment -- virtually everyone wanted the new miracle of electric light in their homes and businesses, and given the choice between riding a wet horse through the city's often-muddy streets or trundling along in relative comfort on a covered electric streetcar, most chose the latter.

Rampant entrepreneurship combined with a serious technical limitation of the current being produced in those first years to cause the proliferation of these small and scattered steam plants. Until nearly the end of the nineteenth century, all of the electricity coursing through the city's transmission lines came from reciprocating steam engines connected to dynamos that produced only direct current (DC). (Dynamos produce direct current and generators produce the other flavor, alternating current.) Direct current had one major drawback -- it did not travel well. Potency, and thus utility, diminished rapidly as the current traveled, and DC was virtually useless much more than a mile from the dynamo that produced it. This meant that as the city expanded, new steam-generation plants had to be built in close proximity to where the electricity would be used.

This state of affairs would not begin to end until 1899, when the region's first hydroelectric plant, at Snoqualmie Falls, began sending alternating current (AC) to Seattle. Despite the obvious limitations, Edison championed direct current for nearly two decades, but alternating current, which Serbian American inventor Nikolas Tesla (1856-1943) had made practical in 1887, was by the end of the nineteenth century the American standard.

Confusion Beyond Comprehension

By 1892 Seattle had more than 48 miles of electric-streetcar tracks and an additional 22 miles of cable-car routes, operated by a number of different companies. The financial Panic of 1893 triggered a deep national recession that lasted more than five years and drove many of Seattle's street railways and power plants into receivership, although few to extinction. The economy eventually revived, and by 1899 no fewer than 10 separate street railways were running in the city, most underfinanced and all unprofitable. One historian later reported that the service they provided "ranged from indifferent to abominable" (Blanchard, 57) and another wrote in dismay, "[T]o condense their separate stories into a readable whole would lead into a tangle of organizations, re-organizations, consolidations and receiverships that would be bewildering" (Beaton, 109)

There was barely less confusion on the electrical-generation front. Before the 1893 economic meltdown, electricity providers were proliferating with abandon. A very partial list would include the Seattle Electric Railway and Power Company (1888), the Seattle General Electric Company (1890), the Pacific Electric Light Company (1890), the Washington Electric Company (1890), and the Home Electric Company (1891). The city was ill-served by this hodge-podge of electricity suppliers and street railroads, and for the most part they weren't making anybody any money. Each was its own struggling little neighborhood monopoly, lacking the means, and in many cases the motivation, to properly maintain equipment, much less make costly improvements. Greater utilities clarity was needed in a city fast becoming the dominant urban center of the Northwest and, as it happened, it came from the other side of the country.

Stone & Webster

Charles Stone (1867-?) and Edwin Webster (1867-1950) were MIT-educated electrical engineers who after graduating in 1889 started a consulting firm. Within the span of just a few years, their eponymous company was one of the nation's largest electrical and urban-transportation conglomerates. By the early 1900s it was designing, constructing, purchasing, and managing power plants in six states and controlled electric lighting systems and railways in a number of cities.

William J. Grambs (1862-1943) became Stone & Webster's first Seattle representative. An Annapolis graduate, Grambs moved to the city in 1887 and became prominent in the nascent electrical industry. After the Panic of 1893 he was appointed bankruptcy receiver for several street railways and electricity-generating companies that had become insolvent. Grambs also was the local representative of the General Electric Company of New York and managed Seattle's Consumer Electric Company. At some point, most likely in 1898, Grambs's path crossed that of Stone & Webster. Some sources say that he was the person who first drew the conglomerate's attention to Seattle; others give the credit to Sidney Z. Mitchell, who was associated with Grambs in several enterprises. Both men had an interest in seeing the city's utilities mess straightened out, and Stone & Webster had the resources and the expertise to do it.

In early 1899 Grambs purchased control of the city's Union Electric Company (itself a conglomeration of several smaller suppliers) and the Seattle Steam Heat & Power Company. These were the first of many acquisitions he brought under the management of Stone & Webster, which also wanted to get control over the city's various street railways. That proved a far greater challenge.

The streetcar industry in Seattle was in great disarray, and when partner Charles Stone came west to try to put a deal together later in 1899, he ran into a brick wall. Frustrated, he asked Grambs to recommend someone who might be able to penetrate the thicket. Grambs, then managing Seattle Steam Heat & Power for Stone & Webster, recommended Jacob Furth, a cofounder of Puget Sound National Bank and a man having detailed knowledge of the city's business community. Furth agreed to become Stone & Webster's local representative, and he brought in as an associate the equally influential James D. Lowman, nephew and former financial trustee of Seattle pioneer Henry Yesler (1810?-1892). Together these two pillars of the Seattle establishment, backed by the capital and technical expertise of Stone & Webster, would finally bring some order to the chaos.

The Seattle Electric Company (1900-1912)

Stone & Webster now had three leading Seattle businessmen representing its interests in the Northwest -- Grambs concentrating on electrical-generation properties, Furth and Lowman pursuing the scattered street railroads. The immediate goal was to bring all of both types of assets in Seattle under Stone & Webster's management.

In April 1899 Furth and Lowman petitioned the city council for a 40-year street-railway franchise, telling the press that Stone & Webster had "practically agreed to provide the capital to bring about" consolidation of all the struggling little lines ("Railroads Will All Unite"). On January 19, 1900, Grambs incorporated the Seattle Electric Company, rolling into it the Union Electric Company and the Seattle Steam Heat & Power Company he had purchased the previous year. Seattle Electric was the corporate canopy under which would be gathered all of Stone & Webster's electrical and transportation properties in the Seattle region. On March 8, 1900, the Seattle City Council passed Ordinance No. 5874, which granted to Furth and Lowman a franchise to construct, maintain, and operate street railways in Seattle. The loud protests of advocates for municipal ownership succeeded only in having the franchise term reduced from the requested 40 years to 35 years.

Furth and Lowman moved quickly and by March 31, 1901, they had gathered into the Seattle Electric Company, in addition to Union Electric and Seattle Steam, nine other utilities: Seattle Traction Company, Green Lake Electric Railway Company, First Avenue Cable Railway Company, Third Street and Suburban Railway Company, Union Trunk Line, Grant Street Electric Railway Company, West Street and North End Railway Company, Madison Street Cable Company, and Burke Block Light Plant. They still were not done, and over the next six years the Seattle Electric Company also absorbed the Seattle City Railway Company (1901), Seattle Central Railway Company (1902), Arcade Electric Company (1903), Electric Department of Seattle Gas & Electric (1905), and West Seattle Municipal Street Railway (1907).

By 1907 the Seattle Electric Company controlled all the street railways in Seattle, but Stone & Webster's attempt to monopolize electrical generation was less successful. In 1902 the city's voters overwhelmingly approved a $590,000 bond measure to finance a municipal hydropower plant on the Cedar River. By early 1905 two city-owned generators were operating at Cedar Falls, and Seattle's street-lighting circuits had been transferred from the Seattle Electric Company's lines to those of the city Lighting Department (soon named Seattle City Light), which later that year also began supplying residential customers.

As Stone & Webster's ambitions moved beyond King County, the name "Seattle Electric Company" was deemed too provincial. In 1912 the firm was reincorporated as the Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power Company. In 1918 the conglomerate decided that it wanted out of the street-railway business in Seattle and offered to lease all its holdings to the city. Inexplicably, Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson (1874-1940) countered with a purchase offer of $15 million, approximately three times the market value of the system. Equally inexplicably, Seattle voters approved the purchase and the price on November 15, 1918. In an irony that apparently went unnoted at the time, Seattle took over operation of all in-city electric streetcars on April Fool's Day, 1919. Subsequent investigations found no intentional wrongdoing by Hanson or anyone else, but merely "slack business methods" (Routes, 13-14).

Shortly after the sale, Stone & Webster's Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power Company dropped the word "Traction" from its title and at some later point reversed the order of "Light" and "Power" in its name. In 1951 Seattle City Light purchased all of Stone & Webster's electrical-production and distribution facilities serving the city. In 1997 the Puget Sound Power and Light Company merged with the Washington Energy Company and what had started nearly 100 years earlier as the Seattle Electric Company became known as Puget Sound Energy.