On April 20, 1900, citizens of the then-unincorporated town of Renton submit a petition to the King County Board of Commissioners protesting the use of Chinese and Japanese laborers on county-funded road and bridge projects. King County Commissioner James Boyce responds by saying that the matter is outside the jurisdiction of the county. Private contractors perform the work on behalf of the county and are at liberty to employ whatever labor they wish, as long as they comply with state law. This protest comes after as many as 1,000 Japanese laborers arrived in Seattle aboard the steamer Riojun Maru and were admitted to work in the United States. For several days, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer featured articles reporting the arrival of what they called "little brown men" – that is, Japanese men hoping to find work – as well as requests by labor organizations to the federal government asking for the enforcement of laws that would exclude Chinese and Japanese workers.

Anti-Asian Hostility

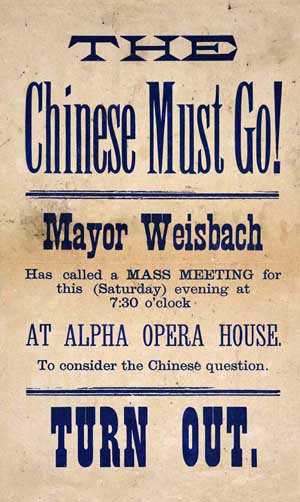

The incident was an early indicator of the wave of anti-Japanese sentiment that swept the West Coast and beyond during the first half of the twentieth century. This wave echoed and continued the anti-Asian hysteria that in the 1880s had led to the forcible expulsion by vigilantes of Chinese workers from West Coast cities, including Seattle and, perhaps, Renton where Chinese were employed in the Talbot coal mine.

Since midway through the nineteenth century, American contractors had relied on imported labor to build the infrastructure of the American west: roads, bridges, railroads, as well as to work the extractive industries. Asian ports offered a steady supply of cheap labor just a steamship ride away from Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle. The Chinese were the first to come and the first to be forced out when nativist agitators whipped up race fears, insisting that the Asians were undercutting white labor, that they could not be assimilated due to language, culture, and even morals, and that they were intent on taking their earnings out of the country, thus sapping the local economy. But labor was needed and so labor recruiters turned to the Japanese.

The Ship

The daily newspapers made much of the Riojun Maru and the large number of Japanese passengers she carried on her arrival in Seattle on April 16, 1900. Numbers vary, but it is clear that there were several hundred Japanese men on board, some of whom were landed at Victoria and the remainder at Seattle. One account speculates that "the little brown fellows" would have an easier time passing immigration inspections in these two cities than they would have in San Francisco. The Seattle Times of April 23 reports that Immigration Inspector C. W. Snyder completed examination of 592 immigrants, 32 of whom were initially refused admittance, but later admitted after a board of inquiry.

The Riojun Maru was by no means the only ship carrying Japanese laborers. Newspaper articles called out several other expected landings and one article in the Times warned that soon "the labor market in the United States will be over-run with 15,000 Japanese as a result of the present enormous influx" (April 17, 1900). The Seattle Post-Intelligencer called the phenomenon an "immigration craze" and suggested that the youth of Japan were being duped by "emigration agents" to leave their homeland with promises of high wages in America (April 19, 1900).

The Riojun Maru, a steamship in the Nippon Yusen Kaisha line, carried both passengers and cargo. The ship brought tons of raw silk, "Oriental wares," and tea to Seattle. An interesting note in the Times of January 26, 1900 lists the cargo on a return voyage to Japan as: "500 bales of cotton and an even 60,000 sacks of flour ... 720 barrels of oil, 1000 cases of canned beef, eleven boxes of printing presses and fixtures, 164 bars of silver bullion, seventeen boxes of bones of dead Chinamen and a varied assortment of beer, machinery, tallow, cigarettes, etc." ("They Ride Bikes"). Most interesting to the paper was the cargo of 250 American-made bicycles.