The Sacred Heart School of Nursing was established in Spokane by the Sisters of Providence in 1898 and operated until its final class in 1973. It was the first nurse-training school in the Inland Northwest. Housed in the Sacred Heart Hospital for decades, the school set high standards for its students. The three-year diploma program graduated more than 2,600 nurses in its 75-year history. Nurses were housed at the hospital, and for years students served as a fresh workforce for the hospital. Nurses from the program provided critical services during both World War I and World War II. As national standards increased in the 1940s, training came to include more classroom time and less bedside care. With the rise of university baccalaureate degrees in nursing, national organizations pressed nursing schools to partner with local colleges. Gonzaga University served as the Sacred Heart School of Nursing's collaborator. As the 1970s unfolded, the changing needs of student nurses led to the decision to close the Sacred Heart School of Nursing. Today, Sacred Heart Hospital continues its relationship with area universities, acting as a location for onsite training for nurses and medical staff.

Sisters of Providence, the Matriarchs of Care

For much of the nineteenth century, hospital care in the West was mostly limited to small buildings or tents. These were often refuges for the poor, as those with means were tended to in their own homes. In 1854 the Sisters of Providence, a Catholic community of sisters in Montreal, Quebec, selected Sister Joseph of the Sacred Heart -- born Esther Pariseau and later known as Mother Joseph (1823-1902) -- to lead a band of missionaries to the Pacific Coast to "carry out the works of charity and education in the West" (Fifty Golden Years, 19). In November 1856, Sister Joseph and four other sisters left Montreal; a month later they arrived at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River in Clark County (where the city of Vancouver would be incorporated the following year).

Equipped with carpentry and design skills that she had learned from her father, Sister Joseph began creating facilities to care for the orphans, ill, and poor of the Vancouver area. Among other facilities she designed, Sister Joseph converted a small building into St. Joseph's Hospital, the first permanent hospital in the Northwest ("Pioneer, Leader, Woman of Faith").

News of the sisters' charitable work and open hearts spread throughout the region. By the 1870s, Mother Joseph was sending nuns to help provide care for the poor in Seattle, and she traveled there to plan a hospital for that city. Eventually their Jesuit brothers to the east in the Spokane Falls area appealed to the Sisters of Providence, hoping they would bring their good works to the growing inland settlement. At the age of 63, Mother Joseph traveled to Spokane Falls in 1886 with Sister Joseph of Arimathea (1842-1906).

Mother Joseph was able to secure land along the Spokane River, not far from the main commercial district of the city (which would shorten its name to "Spokane" in 1891). She used her architectural skills to design a facility, and in 1887 Spokane's first hospital opened. Sacred Heart Hospital offered 30 beds, and the sisters provided all nursing care. Mother Joseph returned to Vancouver and Sister Joseph of Arimathea stayed to serve as the founder and first superior of the facility. By 1888, the demand for care was so great that the sisters decided to expand the hospital. A west wing was designed and completed, doubling capacity at the facility.

In August 1889, a devastating fire ravaged the heart of the city, wiping out the downtown commercial district. The fire threatened the hospital as well, but was stopped short. As the city began to rebuild, the demand for health care continued to increase, as did the demand for trained nurses.

A Growing Need for Care

In 1898 Spokane was home to more than 30,000 people, and reconstruction was still underway. The Jesuits had opened Gonzaga College, and both the Northern Pacific and Great Northern rail lines were bringing work, supplies, and people to the developing commercial center of the inland Pacific Northwest. Medical care within the city was limited to three facilities. Sacred Heart was the largest, but two new facilities, Deaconess Medical Center and Spokane Protestant Sanitarium (renamed St. Luke's Hospital in 1900) were also offering care.

It was not just the influx of people that kept the hospitals busy. Most jobs in the area were high risk: construction, railroad work, cutting timber, mining, farming, ranching, and lumber mills. The Spanish American War also created a need for more highly skilled nurses nationwide as typhoid and yellow fever spread among the troops.

As soldiers returned home, the need for higher standards among nurses was spreading. So too was the simple need for more nurses in the Inland Northwest. A transition period in health care was beginning. Because of advancements in medical training and technology, hospitals were no longer just refuges for the poor. By the end of the century, doctors had better knowledge and technology to aid patients. They could control their surroundings, services, and tools better in a hospital than when providing in-home care. Wealthy and working class citizens no longer shunned hospitals as "warehouses for the destitute or the first step toward death and interment" (Shideler, 27).

Sacred Heart Hospital Nurse's Training School

By 1898, the demand for hospital care had grown beyond what the sisters themselves could supply. Urged by the leadership in Montreal, the sisters of Sacred Heart began encouraging young women into nurse training. The Sacred Heart Hospital Nurse's Training School opened in 1898. The school was later renamed the Sacred Heart School of Nursing.

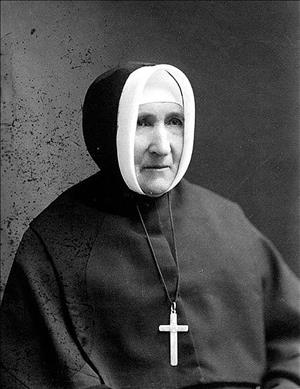

The first supervisor of the school was Sister Emerita, a graduate nurse and a registered pharmacist. To enroll in the rigorous program, a young woman had to be between the ages of 20 and 30 with a good education. She had to submit an application and include letters from both her pastor, testifying to her good character, and her doctor, documenting her good health. Once enrolled, the applicant was on probation for a month before being fully accepted into the program. She could be dismissed for poor behavior, weak or inefficient work, or for neglecting her duties. The sisters later explained their need for strict protocol: "rules and provisions in connection with the course are intended not to be onerous, but to perfect the young women for their future profession" (Shideler, 50).

The sisters offered a two-year course of study for the first class, which included mostly patient care and practical training at the hospital. Science lessons for nursing students were not deemed valuable at the time. The sisters soon realized the need for better training, and they changed the length of study to a three-year course for future classes.

The students lived in the hospital, served at the hospital, and for 10 months of the year learned from a series of three lectures per week (delivered by Sacred Heart staff physicians). "They must become skilled in many things, including assisting in the operating room, making up prescriptions and conducting the duties of the professional nurse" (Thordarson, 9). Specifically, they were taught how to perform multiple bedside tasks, including how to bathe and move patients; how to take a patient's pulse and temperature; how to check the skin, secretions, and wounds; how to prevent and treat bedsores; how to apply dressings; and how to withdraw infection from wounds.

The students were provided a uniform and laundry services, and they were paid $5 per month. If they became sick they were given free care but had to make up the lost time. They were given one afternoon per week off to themselves. Along with the bedside and technical training, the lessons were bound in Catholic doctrine and grace, building character within each student: "Suppose that patient were your Father or Mother ... The poor are God's own ... To be a good nurse one must first of all be a good woman" (Fifty Golden Years, 53).

Students were utilized as a fresh workforce at the hospital. Student nurses were trained on the spot, with little time spent on the science behind the care. This ideology would eventually change.

On June 18, 1900, the school graduated its first two students, Ella Sullivan and Anna Arnold. Class sizes increased, and a year later the other two hospitals in town, Deaconess and St. Luke's, opened nursing schools to support their services as well.

Changing with the Times and Technology

As the medical field evolved, so did standards. In 1909, the Washington State Legislature enacted a law requiring new nurses to pass an exam. They also had to be at least 20 years old with a diploma from a reputable hospital's nurse-training school. The state required two years of training, which Sacred Heart's program already exceeded. The school's class of 1912 was the first crew of Sacred Heart nurses to take the state examination and earn the qualification of "registered nurse."

A need for more beds at Sacred Heart Hospital pressed the sisters to begin a decade-long process of creating a new facility on Manito Hill. The six-story building took up an entire city block and had the capacity to accommodate up to 1,000 patients. The building opened its doors in 1910, one year after the state tightened the rules for obtaining a license to practice medicine. This helped raise standards of medical care throughout the state, and Sacred Heart was well-known for exceeding those standards. At the new Sacred Heart Hospital, the most modern and scientific equipment found on the market was installed, with competent technicians selected take charge of the laboratories, x-ray machines, and other equipment.

In the new building, the nursing school occupied the sixth floor, but before long this space became inadequate. From 1913 through 1936 the School of Nursing graduated an average of 24 students annually. During that time, Sacred Heart treated approximately 4,000 patients each year. The care was provided by an average of 39 sisters, 60 graduate and student nurses, and 25 employees.

The Call Expands Overseas and at Home

On April 6, 1917, the U.S. entered World War I, and a new demand for nurses arose. More than 20,000 nurses responded to the call of the Red Cross from every corner of the nation. But it was not enough. Nursing schools reduced their admission and graduation requirements to get more nurses into the field. Sacred Heart nurses were urged to join the ranks of the military.

"Sacred Heart sends forth a goodly band, thirty in all, and stretches its resources to the utmost in the effort to prepare more to send and to replace, for the local need, those who have left. Many of those who left did not return to the states. One, Norene Royer, class of '16, was the only nurse from the State of Washington who died overseas" (Thordarson, 26).

While serving in England during the war, Royer contracted the virulent strain of flu then sweeping the world. She died in September 1918, and was given all military honors and buried in the American Legion's plot in the Riverside Cemetery in Spokane. Because of the war, Sacred Heart's nurses were scattered across the globe. It was estimated by The Spokesman-Review that 43 of the Sacred Heart School of Nursing's 169 graduates were serving in the war effort. This left a fairly small number to help serve the Spokane community.

In the fall of 1918, Spokane braced for a new emergency. The influenza was becoming an epidemic nationwide. At first, local citizens thought the city would be buffered from the East Coast pandemic. But by the first week of October, Spokane had reported approximately 100 cases of flu. City health officials began closing places of public gathering, including schools, churches, theaters, and other facilities, urging people to stay home. While the precautions proved helpful, they did not stop the spread entirely. "On October 13, nurses were so busy that not a single one was available by the afternoon to attend to new cases" ("Nurse Famine"). Hospital bed space and medical supplies were scarce. Thousands of patients swarmed the local hospitals. Noreen Salvino Kimerer explained that "hospitals were so crowded that victims were being cared for in army barracks, hotels or any place where space was available ... many nurses became ill with the disease" (Thordarson, 26).

With the end of World War I and the spread of influenza and tuberculosis, the public became more aware of the need for qualified, highly trained nurses.

Continued Growth

By 1919 Sacred Heart needed more patient beds and more nurses. The sisters also needed to provide their student nurses with more adequate housing than the sixth floor of the hospital could provide. After securing permission from Montreal, they began construction of a new southwest wing that would include the nurses' school and housing. The new wing opened in 1923, and the student dormitories and classrooms occupied four stories of this annex.

Hospital patient volumes doubled by 1920 to almost 8,000 a year. The number of student nurses also doubled, helping staff with the increased patient load. With a focus on high standards, the Sisters of Providence continued to mandate that care at Sacred Heart meet national standards. Physicians joining Sacred Heart's medical staff had to adhere to the standards set by the American College of Surgeons. Strict guidelines were set for obstetrics and maternity care, and nursing students were required to have several weeks of training in obstetrics. There was a renewed interest in addressing the fact that nurse trainees were still seen as a work force, often to the detriment of a full education.

In the early 1920s, the Rockefeller Foundation funded a study of nurse training. The study concluded that all facilities employing public-health nurses should require hospital training and post-graduate work. It also recommended that nurses train at a university level. In 1925, a national Committee on the Grading of Nursing Schools formed and held a study to grade and classify schools of nursing. The study also evaluated the duties and scope of the profession. The study showed that most hospital-based schools provided inadequate education and their primary purpose was to staff hospitals with an unpaid labor force. This led to reforms in nurse training and development of professional standards. It also led to a process of accreditation for nursing schools.

The Sisters of Providence examined the way their nursing schools were operating. They ensured that their hospitals met or exceeded the requirements for nurse training. Nursing students began learning a full expanse of medical knowledge beyond standard nursing procedures. They were taught subjects ranging from chemistry and dietetics to gynecology and orthopedics.

Sacred Heart Hospital continued receiving high marks as an institution and received a Class A rating from the American College of Surgeons. The hospital continued to expand its technology and make improvements. The national standard of nurse training continued to rise as well. Pressure rose to integrate university education into nursing schools. In the mid 1930s the Sacred Heart School of Nursing again responded to national efforts to raise nursing education standards. One result was the integration of academic courses taught at Gonzaga University into the nursing program.

Difficult Times

While local communities were struggling with the effects of the Great Depression in the 1930s, Sacred Heart Hospital became nationally recognized as one of the best in the country. In 1936, roughly 60 percent of Spokane's nurses were regularly employed and 33 percent temporarily. Nursing was primarily a woman's vocation, and a nurses' average age was 26. Private-duty nurses earned an average of $935 per year, while a hospital nurse earned $1,548. At that time, Spokane had an abundance of nurses, one for every 181 city residents, compared to the state average of one nurse for 341 citizens.

The daily routine at the nursing school was regimented. "Students were awakened by the rising bell at 6 a.m.," followed by roll call, shoe inspection, and "everyone at their places for prayer" in the dining room by 6:35 a.m.; in addition uniforms were to be "scrupulously neat" (Thordarson, 70). Smoking in uniform, alcohol use, absence overnight without permission, incompetence, or marriage could get a student dismissed. To pass the Washington State Board examination, students had to be competent in anatomy, physiology, bacteriology and communicable diseases, dietetics, history of nursing, ethics, hygiene, material medica, medical nursing, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and surgical nursing.

When the U.S. entered World War II in December 1941, Sacred Heart graduates again answered the call of duty. By June 1942, 139 nurses from Washington had enrolled in the First Reserve of the Red Cross nursing service, and 49 of those were graduates of the Sacred Heart School of Nursing, the most of any nursing school in the state. The school participated in the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps program, and in 1943 organized a "Step-Up Victory Program" with Gonzaga. "Enrollment grew so quickly that additional classes had to be added to the program to accommodate the new students" (Thordarson, 89).

During the war years, the hospital relied on the student nurses to perform many duties left by registered nurses who were serving on the front lines.

Big Changes

After the war, another round of standardization hit nursing schools throughout the nation. The American Nurses' Association lobbied for higher wages and accreditation of nursing schools. A new study funded by the Carnegie Corporation suggested that nursing schools be established within universities, and that a college degree be required to practice nursing. At the time, 70 percent of registered nurses were graduates of hospital-based programs rather than universities. They had received diplomas, not baccalaureate degrees. This new suggestion did not sit well with nurses, and they felt that their training had been devalued.

Sacred Heart School of Nursing carried on and continued working with its university partner, Gonzaga. In 1941, Gonzaga had begun offering a Bachelor of Science program for nurses. It required two years of university courses and two and a half years of hospital-based training. A few years later, Gonzaga offered a four-year Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree, which required nursing classes at Sacred Heart. In addition, Sacred Heart continued to offer its three-year diploma program, which included classes taught by Gonzaga faculty. When students graduated from Sacred Heart, they had earned credits from Gonzaga that they could apply toward a degree at a later date.

Enrollment rates were high after the war. Soon the southwest wing of the hospital was too small to host the students. Leadership decided to build a separate location for the nursing school on the southeast side of the hospital campus. The cornerstone of the new building was blessed on April 12, 1946. The new building could accommodate up to 300 students, and included a spacious living room, kitchenette, large classrooms, and two floors for sleeping quarters and social rooms.

In August 1950 Sacred Heart School of Nursing celebrated the 50th anniversary of its first graduating class. The Jubilee celebration began with grand openings of both the new nursing school building and a south center addition to the hospital. The hospital and nursing school had expanded greatly, both in physical and social capacity.

In 1951, the school graduated its first African American student, Clara Monroe. The Missoula, Montana, native received her diploma accompanied by an ovation from the audience. Also in the 1950s, the first male students enrolled in the school. In the late fifties, leadership tore down another social barrier by allowing students to marry during their final year of school.

While changing with the times, Sacred Heart did not lower its high standards of training. In 1954, the school became one of only 5 percent of nursing schools in the U.S. to receive full national accreditation by the National League for Nursing ("League Notices Nursing School").

In the 1950s, students' rooms were regularly inspected and their uniforms were to be well maintained at all times. Casual dress was only allowed in recreational rooms and during informal gatherings. Leaders of the school organized movies, barbecues, formal winter balls, mixers, picnics, and other activities to allow the students time for leisure and to boost morale. The students were also involved in activities beyond the walls of the school, as family and friends often visited.

"Male guests waited for their dates to come downstairs, seated in a 'Beau Parlor' next to the housemother's desk, presumably for close observation ... The student guide admonished students not to loiter at the door with their boyfriends after a date as this 'conduct does not add dignity to the school.'" (Thordarson, 119).

By 1960, Sacred Heart Hospital relied on more than 1,100 doctors, nurses, technicians, and other personnel to keep the facility running smoothly. In the spring of 1961, the nursing school lifted the ban on married women enrolling. Administrators also raised the age limit to 45. While they loosened some entrance requirements, others still maintained rigid qualifications.

"To assure a class of qualified students, nursing schools have adopted entrance requirements that are stricter than those of many colleges. A girl must be a high school graduate from the upper half or upper third of her class, undergo a careful physical examination and, in many cases, an aptitude test. Emotional stability and the ability to work effectively in emergency situations are necessary prerequisites" ("Nurse Training Now Better").

The End of an Era

Technology and medical breakthroughs continued through the 1960s, and Sacred Heart continued to rise to the new challenges. It again needed more space to keep up with the patient load. The sisters gained permission to plan the construction of a new facility in 1967, and the cornerstone of the new hospital was laid on September 10, 1968. In 1971 the new $35 million, nine-story Sacred Heart Medical Center opened with 623 beds, and the ability to accommodate helicopter landings on the roof.

As the 1970s unfolded, the changing needs of student nurses led to the decision to close the Sacred Heart School of Nursing. In 1970, Sister Peter Claver (d. 1991), hospital administrator at the time, announced that the school would close. More and more universities were hosting nursing programs and offering baccalaureate degrees. Hospitals no longer needed to carry on nurse training.

On March 24, 1973, the Sacred Heart School of Nursing graduated its final class. Throughout its 75 years of nurse training, the school graduated more than 2,600 nurses with its characteristically high standards. In the fall of 1974, plans were made to convert a portion of the nursing school facility into a replacement for the St. Joseph Nursing Home.

As of 2017, Sacred Heart Medical Center continued its relationship with area universities, providing a location for onsite training of nurses and medical staff.