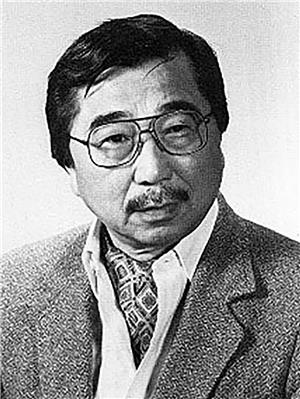

In a remarkable show of personal courage, Seattle native Gordon Hirabayashi was one of handful of Japanese Americans nationwide to defy U.S. government curfew and "evacuation" orders issued in 1942 (in the context of World War II) to persons of Japanese ancestry who lived on the West Coast. Hirabayashi considered the orders to be a gross violation of Constitutional rights. He was arrested, convicted, and imprisoned, and eventually appealed his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Although the Supreme Court upheld his conviction at the time, the fight to overturn it resumed in the 1980s, culminating in his judicial vindication. After the war, Gordon Hirabayashi became a sociologist. He spent most of his career teaching at the University of Alberta, in Edmonton, Canada. He died on January 2, 2012.

Boyhood and Youth

Gordon K. Hirabayashi was born in 1918 in Seattle. His parents ran a vegetable store in Auburn. His father was an immigrant truck farmer who had arrived from Japan in 1907, when he was 19. His mother arrived from Japan in 1914, when she was also 19. In his interview in The Courage of Their Convictions (by Peter Irons), Hirabayashi states that his parents' marriage was arranged in Japan, but that they were married in the United States. Gordon was the oldest of five children.

Both parents had been raised Buddhist, but both converted to Christianity while taking English lessons in preparation for emigrating to the United States. Both came under the influence of an English instructor who was a disciple of a Protestant sect, Mukyokai, which had a pacifist orientation similar to the Quakers.

Both parents encouraged him to stand up for his beliefs. In his words:

"My parents did not allow Sunday sports or work, except during emergencies like harvest time. Their lives emphasized the oneness of belief and behavior. My father was sometimes accused of being baka shojiki, which is roughly translated as stupidly honest. For example, while packing crates of lettuce, he would not make the usual spectacular selection of the outstanding heads for the top row. If my father was the quiet and solid foundation of the family, my mother was the fire, providing warmth and sometimes intense heat. She was an activist — outgoing, articulate, feisty" (The Courage of Their Convictions, pp. 50-51).

In 1937, Hirabayashi entered the University of Washington and participated in many student organizations, including religious groups and the YMCA. He also joined the Japanese American Citizens League. Over the next few years he became a religious pacifist.

On December 7, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Hirabayashi learned the news with others while they were standing outside the Friends Meeting after the Meeting for Worship. Hirabayashi recalls the moment.

"I remember that December 7, 1941 was a quiet Sunday morning in Seattle. We had just finished Meeting for Worship at the Friends Meeting and we drifted outside for visiting. Then, one of our members, who had stayed by the radio, broke the news. Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii! We are at war! It was unreal. The impact did not sink in for some time. My immediate worry was what would happen to my parents and their generation. Since they were legally ineligible for American citizenship, war with Japan instantly transformed them into 'enemy aliens'" (The Courage of Their Convictions, p. 52).

Hirabayashi, then a college senior, applied for and was granted conscientious objector status by the United States government.

Two months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) signed Executive Order 9066, setting in motion the forced evacuation of Japanese Americans on the U.S. West Coast. More than 110,000 people, two thirds of them American citizens, were removed from their homes and neighborhoods and imprisoned in 10 camps located in isolated inland areas.

Principled Resistance

In keeping with his deeply held beliefs, Hirabayashi could not accept the injustices of the curfew and the eventual removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans. He viewed these as gross violations of his constitutional rights. "As an American citizen," he told scholar Ronald Takaki, "I wanted to uphold the principles of the Constitution, and the curfew and evacuation orders which singled out a group on the basis of ethnicity violated them. It was not acceptable to be less than a full citizen in a white man’s country."

Hirabayashi joined the Quaker-run American Friends Service Committee, helping Japanese American families whose fathers had been imprisoned immediately after Pearl Harbor. The day after Japanese Americans were removed from Seattle for a temporary prison camp at the Puyallup Fair Grounds, Hirabayashi remained in the city, defying the military order that had required "all persons of Japanese ancestry" to register for the "evacuation." He turned himself in to the FBI, and was tried and convicted in October 1942. He went to prison for 90 days. His case before the Supreme Court, Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), was the first challenge to the government’s wartime curfew and expulsion of Japanese Americans. The Court ruled against him 9-0.

Post-War Life

After the war, Hirabayashi resumed his education, receiving B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. degrees in sociology from the University of Washington. He then taught at American University in Beirut for three years and at American University in Cairo for about four years. His discipline concerned comparative cultural studies, largely concerning Middle Eastern and Asian cultures. In 1959, he joined the faculty at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, where he was sociology chair for seven years beginning in 1970. He retired in 1983.

His first marriage was to Esther Schmoe. She was the daughter of Quaker peace activist and conscientious objector Floyd Schmoe (1895-2001). Gordon and Esther Hirabayashi had three children, twin daughters Marion and Sharon, and son Jay. Their marriage ended in divorce. (Esther Hirabayashi died in January 2012, 10 hours after the death of her former husband.) Gordon Hirabayashi's second marriage was to Susan Carnahan, who survived him.

The New Case

In the 1980s, 40 years after his wartime convictions, Hirabayashi challenged the decisions with a little used legal recourse called coram nobis, which allowed for judicial review of a judgment based on factual error not known to the court at the time the judgment was delivered. Researchers and legal scholars Peter Irons and Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga had uncovered irrefutable evidence that the government had withheld information from the Office of Naval Intelligence, contradicting the United States Army’s claim of widespread disloyalty among Japanese Americans. This was the so-called "military necessity" rationale for the evacuation. In fact, not one Japanese American was ever convicted of sabotage or espionage during the entire war.

Hirabayashi’s exclusion and curfew convictions were overturned in 1986 and 1987 respectively. Although the Supreme Court rulings remain intact because the government chose not to appeal the reversals, his legal victories made history in disproving the government’s contention of disloyalty. Of the cases, Hirabayashi said:

"When my case was before the Supreme Court in 1943, I fully expected that as a citizen the Constitution would protect me. Surprisingly, even though I lost, I did not abandon my beliefs and my values. And I never look at my case as just my own, or just as a Japanese American case. It is an American case, with principles that affect the fundamental human rights of all Americans: (The Courage of Their Convictions, p. 62).

Hirabayashi resided for many years in Edmonton, Alberta, where he was professor emeritus in sociology at the University of Alberta. He died in Edmonton on January 2, 2012. He had been suffering from Alzheimer's. On May 29, 2012, President Barack Obama in a White House ceremony awarded Hirabayashi the Medal of Freedom, posthumously.