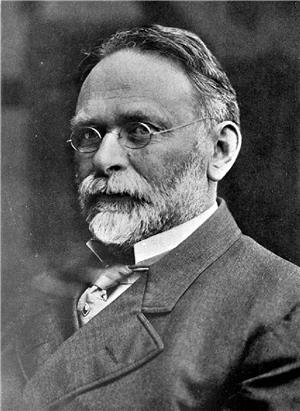

Reginald Heber Thomson probably did more than any other individual to change the face of Seattle. During his exemplary career as city engineer and beyond, he leveled hills, straightened and dredged waterways, reclaimed tideflats, built sewers, sidewalks, tunnels, and bridges, and paved roads. He was instrumental in creating the Cedar River watershed, City Light, the Port of Seattle, and the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks. In fact, virtually all of Seattle’s infrastructure can be attributed to R. H. Thomson.

Upon Arrival, He Surveys the Situation

Thomson was born and raised in a Scottish colony in Hanover, Indiana, and graduated from Hanover College with a doctorate of philosophy in 1877. He first worked as a surveyor, but when his father accepted a post as principal of the Healdsburg Institute (the future Pacific Union College in Oakland, California), Thomson followed him there to teach mathematics. In California, Thomson met T. B. Morris, who had been in the Washington Territory looking for coal. In 1881, Thomson accompanied Morris to Seattle by steamer. They arrived on September 25, 1881, the 30th anniversary of the arrival of Seattle pioneer David Denny (1832-1903). That afternoon Thomson met Denny at a memorial service for slain U.S. president, James Garfield.

Denny pointed out that 30 years before, there had been exactly four people present, whereas now there were 3,500. Thomson took note of the crowd, but couldn’t help also noting the rudimentary state of city development. Seattle in 1881 was a pastiche of wood houses and buildings connected by dirt roads that crisscrossed the hills leading up from the shoreline. South of the city lay a shallow, muddy arm of Puget Sound, which cut off the city from the valley to the south. Thomson wondered how people could do business in and around this port city with hills, ruts, and mudflats everywhere impeding their movement. He’d soon change all that.

Early Work

Thomson entered into a partnership with F. H. Whitworth, the city and county surveyor. One of Thomson’s early tasks as assistant surveyor involved the initial work of dredging a canal between Lake Washington and Lake Union where, decades later, he would be instrumental in constructing the Lake Washington Ship Canal connecting both lakes to Puget Sound. In 1884, Thomson became the city surveyor. In this role he built Seattle’s first sewers and the Grant Street bridge across the tideflats.

He resigned in 1886 to work for the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern railroad. As locating engineer, he plotted the path of the railbed from the northern end of Lake Washington all the way eastward through Snoqualmie Pass, to Lake Keechelus. Not stopping there, he moved on to Spokane for a few years where he constructed terminals and built two bridges.

Once back in Seattle, he worked as a consulting engineer. Then, in 1892 he became city engineer, a job that he would hold for the next 20 years. He added 4.5 miles of sewer lines throughout the city, much of it through formations that had stymied earlier engineers. He also worked on creating the growing community’s first sidewalks and paved roads, including Lake Washington Boulevard, which he and his assistant, George F. Cotterill (1865-1958), first designed as a cinder path for bicycles.

Moving Mountains

Still, the hills, valleys, and mudflats in the downtown area vexed him. Thomson believed that the prerequisite for commercial growth and progress was flatness, allowing for the easy movement of traffic. For the next two decades, he attacked the hilly landscape with tenacity and fervor, forever changing Seattle's appearance. His first regrade, in 1898, was up 1st Avenue from Pike Street to Denny Way. Five years later, Pike and Pine were regraded from 2nd Avenue to Broadway. For the next eight years, Thomson’s crews pummeled Denny Hill, between 2nd and 5th Avenues, and Pike Street and Denny Way.

Thomson also went after the hillock between Main and Judkins Streets and 4th and 12th Avenues. Dearborn Street was regraded, and the 12th Avenue Bridge was built to Beacon hill. He created Westlake Avenue, which provided level access to Lake Union.

In all, Seattle regraded 25 miles of streets, which displaced 16 million cubic yards of dirt. This dirt was poured into the tideflats south of the city, the landfill creating a whole new industrial section for the burgeoning metropolis. When James J. Hill (1838-1916), owner of the Great Northern Railroad, established his terminus in Seattle, Thomson convinced him to bypass the waterfront's already crowded Railroad Avenue (now Alaskan Way) and establish King Street Station south of Pioneer Square. Thomson had a tunnel built beneath the city from Virginia to Washington Streets, which was completed in 1906. Thomson met the challenge of reshaping Seattle, and while accomplishing this task he was also working on his greatest achievement.

Water, Water, Everywhere

In pioneer days, Seattle residents received water from a reservoir on Beacon Hill filled with water pumped from Lake Washington. As the city grew, this system became woefully inadequate. Thomson, realizing that the city would become even larger, looked towards the Cedar River Watershed, located 30 miles southeast of Seattle in the foothills of the Cascade mountain range, as an abundant source of clean water for generations to come.

Miles of pipeline were required to bring this water to Seattle, and some felt this to be extravagant. Many people did not share Thomson’s vision that Seattle would one day become a thriving metropolis. During his first seven years as city engineer, Thomson waged an uphill battle to convince the region that this water system was necessary. By 1899, work on the pipeline had begun in earnest. Thomson’s plan was to use wooden barrel-stave pipes for most of the line, and steel pipe in areas of highest pressure. As the line was being installed, the firm that manufactured the rods and shoes suddenly refused to fulfill specifications. Thomson took the train to their factory in Denver and, without identifying himself, asked if they could furnish stave pipes and fittings quickly. Anxious to receive another contract, they assured him they could, at which point Thomson told them who he was. He told them that he was returning to Seattle, and hoped that he didn’t have to go to court in order to obtain his materials. He had no further trouble with the firm, and work continued apace.

On December 24, 1900, a test was made of the water flow to look for leaks. The system worked well enough that on January 10, 1901, water began flowing into the Volunteer Park reservoir in Seattle. More than a century later, Seattle and King County still use the Cedar River watershed.

City Light

Thomson’s use of the Cedar River did not end with the capture of water. Next he harnessed it to provide electricity. Thomson and his crew designed and built the City Light Cedar Falls hydroelectric plant, which went into operation on October 4, 1904. On January 10, 1905, electric current illuminated streetlights in Seattle, and by September 9, City Light began serving private customers, which it does to this day.

At the urging of the city council, Thomson was asked to take a well-deserved vacation from all of his good work. He visited Europe, where he “made examination of nearly everything connected with city life, such as water, lights, sewers, conditions accelerating city growth, cities’ fire control, municipal baths, municipal laundries, and so forth.” Six months later, he returned from this “vacation” more energized than ever. There was more work to do.

City Light was running efficiently, and work continued on the regrades. Thomson turned his attention back to sewage management. He set his sights on a sewage outfall on West Point in Magnolia. When the commander at Fort Lawton balked, Thomson took it up with then Secretary of War, William H. Taft, and showed that the outfall would be well into Puget Sound. Thomson got the okay.

Somehow during all this, from 1905 to 1915 Thomson also became president of the University of Washington’s board of managers. And he found the time to examine the flow of commerce along Seattle’s waterways. This interested him so much, that he resigned as city engineer in 1911 to organize the Port of Seattle, established largely through his efforts at lobbying the state legislature. Under Thomson's direction as engineer, the Port Commission made far reaching developmental plans, many of which are still in effect. While on the commission, Thomson pushed for acquisition of Smith Cove and the foot of Bell Street for use by the Port. He advocated deepening and straightening the Duwamish River for use in the industrial area, and also campaigned in Washington D.C., for funds to build the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks.

A Tireless Individual

One would think that after such a career, retirement would be in the offing. Not for Thomson. As he approached 60, he persevered on many projects. From 1916 to 1922, he was a member of the Seattle City Council, yet he continued to do engineering work. He was a consultant on the Rogue River Valley Irrigation canal, and built a hydroelectric plant in Eugene, Oregon. He was in charge of water development in Bellingham. He surveyed power-plant sites in Southeastern Alaska. He returned, temporarily, to his job as Seattle city engineer in 1930 to oversee the final work on the Diablo Dam on the Skagit River. After that, he was a consulting engineer for both the Wenatchee Metropolitan Water System and the Inter-County River Improvement Commission for Pierce and King counties. He also consulted on the construction of the Lake Washington Floating Bridge and for the foundations of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Thomson enjoyed his work too much to retire.

“Did You Get Everything Done?”

Reginald Thomson died on January 7, 1949, at the age of 92. Immediately prior to his death, he wrote his autobiography, That Man Thomson (published posthumously). In it he noted that in his later years, he was constantly asked by those who knew of his great achievements, “Did you get everything done that you wanted to get done in improving Seattle?”

His answer: “No. So far as I can see, no one can determine the completeness of anything done or built for a city because a city is a growing thing, and what might satisfy today will be insufficient tomorrow. My work for Seattle has been concerned with doing what needed to be done each day so that growth would not be retarded, and with planning for whatever growth might occur tomorrow.”