The Queen Anne counterbalance was a stretch of Seattle streetcar line with an unusual feature: a pair of tunnels, right below the tracks, containing heavy miniature rail cars that acted as counterweights to the electric trolleys above. It was installed in 1901 on the steepest part of Queen Anne Avenue and operated until the city’s streetcar system was dismantled in 1940. The underground rail cars were loaded with iron and concrete and connected to the trolleys via cables and pulleys. When the trolleys were headed uphill, the counterweight cars were headed down, serving as 16-ton boosts. When the trolleys were headed downhill, the counterweights were headed up, serving as supplemental brakes. Attendants at the top and bottom attached and detached the cables. The counterbalance made electric streetcar service possible for this popular neighborhood, because electric trolley cars had trouble maintaining traction on steep roads such as Queen Anne Avenue.

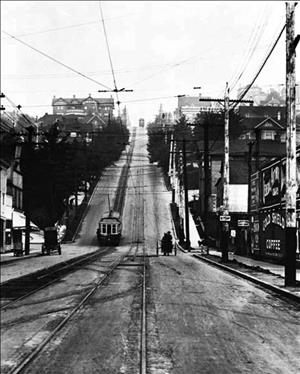

Steep Path up Queen Anne Avenue

In the beginning, the street rail line running up Queen Anne Hill was neither a counterbalance line nor an electric trolley line. It was a cable car line, part of the Front Street Cable Railway, one of Seattle’s original cable car routes. Cable cars used a fundamentally different form of propulsion, in which cars were pulled by underground cables, powered from a central steam plant.

The Front Street Cable Railway had been launched in 1889 to serve the downtown business district. It ran from Front Street (1st Avenue) in Pioneer Square to Denny Way. In 1891, it was extended northward to ascend steep Queen Anne Avenue to its terminus at Highland Drive (this stretch was incorporated by the same entrepreneurs under the name North Seattle Cable Railway Company). Cable car propulsion was ideal for Queen Anne, since cable cars handled hills better than electric trolleys.

Cable car lines were also expensive to maintain. Within a few years, the Front Street Cable Railway went into receivership. In 1900 it was snapped up by the Seattle Electric Company. As the name implies, this was an electric trolley company – it would evolve into Puget Sound Power & Light (today’s Puget Sound Energy) – and it had no interest in operating a money-losing cable car route. It immediately began ripping out the cables and stringing up electric trolley wires.

Yet the Seattle Electric Company had a serious engineering problem to solve at Queen Anne Hill. The grade, up to 19 percent at places, was simply too steep for conventional electric streetcars. So, for the stretch of five steep blocks between Roy Street and Comstock Street, the company turned to counterbalance technology. Similar systems were in use elsewhere, including on Fillmore Hill in San Francisco, in which electric streetcars running in opposite directions counterbalanced each other. A few lines in Seattle and other cities employed above-ground counterbalance systems. On Queen Anne Avenue, however, Seattle Electric Company engineers designed a different kind of system, with an underground tunnel directly beneath the tracks. Heavy iron rail cars, no taller than waist-high, were loaded with concrete, to serve as eight-ton counterbalances. The counterbalance cars were then attached via cables and pulleys to the electric trolley cars.

The theory was simple enough. The iron and concrete rail car would serve as a multi-ton boost when a trolley was going uphill, and would act as a brake when the trolley was headed down. Since the counterbalance rails were buried below grade, most riders wouldn’t even realize they were there. Work began right away and by early 1901, the tunnel was dug, the rails laid, and specially equipped electric trolleys were lumbering up and down Queen Anne Avenue. Initially, this was only a single track operation.

Counterbalance Trials and Tribulations

Operating the Queen Anne counterbalance proved to be complicated and more than a little dangerous. Counterbalance attendants were stationed in little booths, at the top of the hill and the bottom. Approaching trolleys would stop at the booth and the attendant would step out and attach the cable to the trolley with a "double-locked shoe" ("Cars That Run ... "). Getting the cable firmly attached was critical. Often, the counterbalance attendant would also have to jump down into the tunnel to adjust weights on the miniature rail cars. The weight was usually sufficient to offset a normal trolley car, but if the trolley was especially crowded, the man would have to pile on extra concrete or iron. When the attendant estimated that the weights were correct, he would climb out and the motorman would start the trolley rolling, which would in turn start the underground counterbalance car rolling in the opposite direction. If all went well, the trip went smoothly and steadily.

All of this activity caused inevitable delays. On the single track, trolleys could run no more frequently than every 10 minutes. The complexity of the system also meant that the line was frequently shut down for repairs. In fact, the Seattle Electric Company was apparently not enamored with its own counterbalance operation. In May 1901, the company floated an ambitious plan to abandon the counterbalance entirely and build a 600-foot-long streetcar tunnel instead – in essence, a subway beneath Queen Anne, several blocks west of the existing line. The Seattle Electric Company general manager said this plan "would remove the constant menace that the people and the company are placed under by the present counterbalance system, with the liability to mistakes on the part of employees" ("A Tunnel for ... "). Queen Anne residents vigorously opposed this tunnel scheme as "preposterous" and unrealistic, and it never reached fruition ("The Queen Anne Tunnel"). The counterbalance remained.

The general manager's concerns, however, turned out to be well-founded. Just five days after he floated the plan, one of the counterbalance cables snapped. A trolley was headed downhill at the time, but it was able to brake itself adequately and get safely to the bottom. The underground rail car, freed from restraint, raced downhill and actually beat the trolley to the bottom. The concrete-laden car ended up wedged in its underground planking and the entire system had to be shut down for two days. On July 28, 1901, another trolley car went downhill too fast, due to a defect in the trolley's braking system, and smacked into a bumper at the bottom. The car was flung sideways off the rails and the glass was shattered. Passengers were shook up, but not seriously injured.

Parallel Lines Speed Service

In 1902, with the tunnel idea shot down, the Seattle Electric Company built a parallel line on the west side of the street, making it a "double counterbalance," that is, with tracks on both sides of Queen Anne Avenue. This meant service could be increased to every five minutes, although it also meant that trolleys sometimes had to run on the "wrong side of the street" (the left side), if the concrete rail car was in the incorrect position when a trolley arrived (Herschensohn, "In Honor of ... "). The company was given a special permit to do so. The two tracks were connected by cross-tracks to move trolleys from one side of the street to another as necessary. This did not, however, solve all of the safety issues. In December 1902, one of the heavy counterweight cars again came loose and careened downhill at the shocking "speed of 150 miles per hour," as estimated by The Seattle Times ("Working Again"). It plowed "through the earth and boards for a distance of twelve feet or more" at the bottom of the tunnel ("Trouble on the Car Lines"). No one was injured.

The accident put the counterbalance out of commission for more than a week, which was a major inconvenience for residents of this burgeoning Queen Anne neighborhood. "Thousands of people who live in the Queen Anne districts must walk up and down the long and unusually difficult hill in going to or coming from town," reported The Seattle Times ("Trouble on the Car Lines").

In 1907, the east track was dug up and completely rebuilt so that it could "handle the large double-truck cars," already in use on the newer west track ("Counterweight Is to Be Closed"). These larger trolleys required two counterbalance cars of eight tons each, for a total of 16 tons. During construction, all trolleys were routed to the west track, which meant frequent delays, but when finished the result was improved service. These and other improvements apparently increased the safety and reliability of the line, because from this point on, notices of closures and repairs came less frequently.

By 1908, the word "counterbalance" had come to refer not only to the trolley line and its mechanism, but also to the steep slope itself. Auto dealers bragged that their most powerful machines were able to climb "the Queen Anne Counterbalance on the high gear" – the ultimate Seattle automotive test (Capitol Hill Auto Club ad). Before long, the word Counterbalance, in its capitalized form, was also being used to refer to the neighborhood itself.

On October 28, 1919, wet and slippery leaves caused one of the most terrifying accidents in the history of the counterbalance. A trolley was headed downhill when the motorman and conductor noticed to their alarm that the car was beginning to slip badly on the wet tracks at about Aloha Street. The trolley’s power brakes failed and the counterweight alone was not sufficient to stop the trolley. The trolley began to pick up speed. The runaway trolley careened downhill for the last two blocks, reaching a speed of 35 miles per hour, simultaneously dragging the counterbalance car rapidly uphill.

The conductor quickly ordered a man off the rear platform and shouted to the other 20 passengers to "brace themselves in their seats." At the exact moment when the counterweight car slammed into the upper terminus, the speeding trolley jerked to an abrupt stop at the lower terminus at Roy Street. The resulting crash could be "heard for many blocks," passengers were "thrown about" and the cable "pulled out the rear trucks and dropped the car squat on the tracks" ("Car Makes Mad Dash ... ").

"The entire rear vestibule of the car was pulled out and the rest of the car passed on six feet clear of the wreckage," said The Seattle Times ("Car Makes Mad Dash ... "). One passenger, a shipyard worker, injured his leg so badly that he could not stand, and had to be carried to the sidewalk for treatment. The others had a "severe shaking up" but were not badly injured. The conductor had the presence of mind to jump from the trolley right before impact, and rolled to the ground without injury. The trolley was a broken hulk but the line itself was soon back in operation. The counterbalance had actually done its job, in a way, by bringing the runaway trolley to a stop, although with frightening abruptness.

More Than 6 Million Passengers Annually

In 1923, The Seattle Times celebrated the city's most unusual rail line with a story titled "Cars That Run Underground in Seattle -- Queer Little Railway That Nobody Sees But Carries More Than 6,000,000 Persons Up and Down Hill Every Year – The Only One of Its Kind in the World." It extolled it as a Seattle wonder, "made in Seattle by Seattle men." Inspector W. W. Wiley, the chief attendant of the counterbalance, said "there are other counterbalances in the country, but none underground that I know of." The others – in Duluth and Cincinnati – were above ground. Wiley explained the mechanics of the system by saying that "the weight of 16 tons pulling on a car weighing from 18 to 22 tons" reduced the effective Queen Anne grade from an average 17 percent to approximately 4 percent.

Wiley declared the Queen Anne counterbalance to be "the best in the world" because "passengers may travel back and forth with not the slightest fear of danger" ("Cars That Run Underground ... "). He said the underground rail cars had steel contrivances called "dogs" that, should the cable break, "automatically shoot out on each side, catch in the timbers along the tunnel and stop the run of the counterbalance cars -- the streetcar above would be in no danger" ("Cars That Run Underground ... "). "Suppose the cable would break!" he was quoted as saying. "The wreck -- if the dogs should fail to work -- would be all underground with the passengers perfectly safe on the street." The Seattle Times credited the counterbalance with providing "the means of opening to Seattle residents the view portion of the city." It had carried millions "up and down a hill that in the old days defied horses and at present is avoided by automobiles" – except, of course, by those drivers trying to prove their superior horsepower ("Cars That Run Underground ... ").

Automobiles, Electric Trolleys Make Rails Obsolete

In 1933, the city-owned Seattle Municipal Street Railway, which had taken over this and all other street railway lines in 1919, undertook a major reconstruction of the counterbalance. "Reconditioning of the counterbalance has become imperative," said the superintendent, because the old tunnels were in such poor repair ("Counterbalance to Be Repaired"). Residents had been complaining about the noise due to worn rails and other equipment.

Yet in the end, no repairs could save the counterbalance, or, for that matter, Seattle's entire street rail system. By the 1930s, the automobile had drastically cut into trolley ridership. The city's transit system was in crisis and hopelessly in debt. In 1936, the city commissioned a report that recommended that the entire street rail system be ripped out and replaced with 135 gasoline buses and 240 trackless trolleys – electric trolleys that run on rubber tires instead of rails. Trackless trolleys, like streetcars, used trolley poles to hook to overhead wires, but otherwise they looked and operated more like buses. They could pull over to curbs to pick up riders, which was now considered a major advantage on the auto-clogged city streets.

The entire plan was controversial, sparking a rancorous three-year debate on the wisdom of scrapping the street railways. The trackless trolleys were central to these debates, since they would be needed for the city's steepest transit routes. The gasoline buses of the time did not have the power or the traction to reliably handle these steep grades. Not everyone was convinced that trackless trolleys could do so, either. Seattle Mayor John F. Dore (1881-1938) told a cheering crowd that the trackless trolley "is all right in its place; so's a pig" ("6,000 Cheer and Jeer ... ").

The proponents of the trackless trolley decided to prove its mettle by doing what auto dealers had been doing for decades: test runs on the Queen Anne counterbalance. In 1937, the city’s transit department imported two trackless trolleys for demonstration purposes in an attempt to convince a skeptical public (not to mention their mayor) of their worth. They strung up an extra pair of trolley wires on Queen Anne Avenue and announced a race between a trackless trolley and the regular Queen Anne counterbalance streetcar.

On March 5, 1937, "scores of citizens thronged the start and finish lines of the counterbalance race," reported The Seattle Times ("Trolley Coach Outraces Car ... "). With transit officials on board, the "demonstration coach sped up the hill, sweeping over the top at 30 miles per hour, in the elapsed time of one minute, five seconds, as the crowd cheered." The counterbalance trolley's best time was 2 minutes, 35 seconds. During one of the trials, the trackless trolley was stationed at the bottom of the hill while the counterbalance streetcar was stationed halfway up the hill. Both started at the same time. The trackless trolley still beat the old streetcar to the top. The trackless trolley had, in the words of The Seattle Times, "embarrassed" the Queen Anne counterbalance ("Trolley Coach Outraces Car ... ").

In 1939, the trackless trolley won an even more significant victory when the city decided once and for all to rip out the entire street railway system and purchase 235 trackless trolleys and 102 buses, with help from a New Deal federal loan. At first, city engineers considered keeping the underground counterbalance apparatus and using it with the new trackless trolleys, as an additional safety measure. Engineers were still debating this issue in mid-1940, when the old streetcars were due to be retired.

A Harrowing Final Run in 1940

The old counterbalance streetcars passed into history not with a whimper, but with what was described as "a cross between an earthquake and a cyclone" ("20 Face Vandalism Charge ... "). On August 11, 1940, a "mob of 70 Queen Anne youths" chose to celebrate the final run of the old streetcar at 1:30 a.m. by storming the trolley, "smashing windows and seats and pelting passengers and operators with fruit and vegetables." They had greased the tracks and stacked garbage cans to force it to stop. Then they jumped on, broke every window and tossed seats into the street. They "routed" the other 40 passengers and threw corn cobs and tomatoes at them. Inspector Wiley, riding on the last run, said they "swarmed over the top of the car," rocked the car and cut the trolley rope ("20 Face Vandalism Charge ... ").

Wiley struggled with the mob for 15 minutes before he could get the car rolling again. It was an empty hulk when it finally limped back to the car barns. The Seattle Times ran a front-page editorial headlined "Mob Violence!" which said, "There is no excuse, no extenuation for such riotous demonstrations. The fact that the car had served its usefulness and was to be retired had nothing to do with the mob’s responsibility for its act" ("Mob Violence!"). Police later rounded up 20 youths, almost all from Queen Anne, on vandalism charges. The head of the Seattle Transportation Commission said he was aware that youths had been planning revelry around the farewell rides, "but we didn't think anybody would touch our poor old Queen Anne trolleys" ("20 Face Vandalism Charge ... ").

History Underground

The poor old trolleys staggered off into retirement, but the counterweight tunnels were kept intact because officials thought they might use them to assist the trackless trolleys in icy weather. As it turned out, they never did. The trackless trolleys did indeed have trouble in the snow, but the counterbalance solution was never attempted. Even today, the counterbalance tunnels remain intact beneath Queen Anne Avenue, unused and unmaintained. For decades stories have circulated of urban explorers sneaking in through the hatchways and walking the old tunnels – or crawling, because in some places the tunnels are only 3 or 4 feet high. One of the hatchways was covered over in 2008 for a small urban park at Queen Anne Avenue and Roy Street.

That park was named Counterbalance Park, in honor of the old trolley system that formed the neighborhood’s identity for nearly 40 years. The name also lives on in Seattle’s Counterbalance Brewing, Counterbalance Barbershop, and Counterbalance Bicycles. The old rail cars no longer rumble below ground, but they are not forgotten.