From 1893 to 1923, the City of Everett was serviced by a network of electric streetcars. The development of this system began before Everett had incorporated and continued through the rapid period of growth that followed. While the system was relatively short-lived, it was a vital means of transportation that enabled countless workers to reach the mills and factories, and scores of residents to access commerce, entertainment, and education.

Early Transportation

For thousands of years, Coast Salish inhabitants traveled the Salish Sea region in variety of canoes designed for open water or river use. Journeys that took people away from waterways had to be done by foot. As non-Native settlers began arriving in increased numbers in the mid-nineteenth century, there seemed to be little reason to build roads because there were few places to go that could not be more easily reached by boat. The sparse networks of roads that were developed in the Territorial period were largely created for military purposes.

Instead of pouring resources into roadbuilding, settlers developed a network of steamships dubbed the Mosquito Fleet that adopted indigenous waterways to become an essential lifeline between far-flung communities along the inland sea. As scattered settlements began to expand into towns and cities in the late nineteenth century, the need for rail transportation to move freight and people reliably became more urgent. Rail transport was less susceptible to delays due to inclement weather, heavy seas, or impassible muddy roads. In the 1890s public imagination fixed on the courtship of James J. Hill (1838-1916), the person responsible for choosing a route and terminus for his transcontinental Great Northern Railway. As boosters for Everett, Seattle, and Tacoma vied for Hill's attention, Snohomish County pursued more modest plans for local commuter and freight rail lines.

Making Plans

The City of Seattle was an early adopter of the urban streetcar system. Started in 1884 with horse-drawn streetcars, Seattle's system had moved to cable power by 1887 and had electric cars by 1889. Discussions of installing a similar system at the Port Gardner townsite began in early in 1892, before Everett had incorporated as a city. Col. J. B. Hawley was awarded a franchise to create a system of streetcar lines that would stretch from Mukilteo to Snohomish, via Everett and Lowell with the entire length of Hewitt Avenue included. In October of that year, Hawley had traveled east to stir up interest among investors in his plan. His first stop was in Cleveland to speak with Joseph Colby, who discussed at length the importance of the Everett Land Company smelter at the north end of the peninsula, and the development of the Everett to Monte Cristo railway. Hawley continued to New York, where he spoke with Charles Colby (1839-1896), Gardner Colby (1810-1879), Charles C. Wetmore, and a Mr. Schenck about their willingness to support his project. The remainder of Hawley's trip east included detailed inspections of electric railway lines in New York, Saint Paul, Minneapolis, and other cities with similar lines.

William F. Brown (1848-1932) was also awarded a separate franchise to develop a system solely focused on reaching different areas of development and industry in what would become the City of Everett; there is little record of his endeavors to push his plan forward. In November 1892, Henry Hewitt (1840-1896), president of the Everett Land Company, met with the different corporations interested in undertaking the streetcar construction. The Everett Land Company was already planning to open large tracts along the proposed lines to quickly sell lots to build housing for the workers to be employed in the tracklaying. To ready the community for the coming streetcars, and to alleviate any inconvenience caused by the construction, the company planned to run a system of horse cars over Hewitt Avenue.

In December 1892 the Everett Daily Herald reported that the contract for the construction of Everett's electric street railway had been awarded, and that A. R. Whitney Jr. was to be the general manager of an unnamed company in charge. Locals started to speculate over where the lines would be, but it was assumed that there would be a loop that ran between the bay and river sides of the townsite up Pacific Avenue and back on Hewitt, as well as a line between Lowell and the barge works and smelter along Broadway. It was vital that the streetcar lines connect the residential, commercial, and industrial areas, as well as transportation hubs along the waterways.

Service Begins

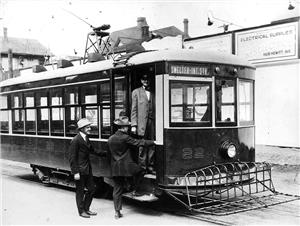

In January 1893 the cars began to be delivered to the townsite for the streetcar lines. By March 16 workers had already begun laying down the tracks and sinking poles into the ground for the electrical lines. Tracklaying began at the smelter site at the north end of the peninsula, and crews worked their way back toward town on Monte Cristo Avenue, which ran parallel and to the west of East Grand Avenue. While a crew of 30 began the work, it was expected that there would be nearly 150 men employed in constructing the lines before the project's completion. Work undoubtedly carried on, but for a while news coverage left the rails for the excitement leading up to the vote to incorporate on April 27, and the scores of published ordinances that were to follow.

On June 29 the Herald announced that the final rail for the Lowell extension was ready to be laid, and that service along the entire system would start July 3. The powerhouse on Bond Street had been running smoothly for days and was ready to be put to the test. A. R. Whitney would be on hand to inaugurate service on the whole line. The intent was for there to be frequent service along Hewitt to accommodate the customers of the businesses on that main thoroughfare. The lines connecting downtown Hewitt to Lowell and the barge works would move workers and occasionally freight. The new car house on Bond Street was also ready to receive and service the sturdy new fleet of cars. It was remarked that in the absence of any formal July 4 observances put on by the new City of Everett, it was safe to assume that the locals would be spending their holiday riding the cars.

Everett Daily Herald coverage on July 6 includes a lengthy piece on the new rail service. The line had been turned over from the construction company to the operation company on the 3rd at 11:30 a.m., and regular service began that day at 2 p.m. The invited guests for the first run included Everett's first mayor, Thomas Dwyer, members of city council, representatives of the press, prominent Everett citizens, and representatives of some of the industries in town. Manager A. R. Whitney Jr. took the first car out to Lowell, followed by superintendent H. C. Wybro's run to the smelter and barge works. J. D. Elmendorf directed the third run on the Hewitt Avenue crosstown line. Guests were given tours of the powerhouse and marveled at the enormous machinery. After the excitement of the first runs and tours, cars immediately began their scheduled routes. On July 4, some 2,600 people rode the streetcars to celebrate the holiday; at the time of incorporation Everett's population was estimated at 5,000.

The inaugural runs of Everett's streetcars were a high point for 1893, as the city, and the nation sank deeper into financial panic. Everett's economic future was uncertain at this time, though those who chose to stay continued to run things as well as possible and develop the city as best they could. The streetcar lines continued to run. They were still privately owned, though in 1894 the Everett Land Company, which by then controlled the Everett Railway & Light Company, tried to sell all of its utility holdings to the city. The bond measure for the purchase was voted down by the citizens of Everett, and rail service remained privately held.

Line Improvements

In 1897, promotional material published by the Everett Commercial Club to entice investors boasted of seven miles of electric streetcar lines in operation in Everett, as well as a modern electric light plant. At that time a line ran down the length of Hewitt Avenue from the Snohomish River to Bond Street. There were also lines on Broadway, and Pacific, Rucker, and Everett avenues.

By the end of 1900 the Everett Railway & Light Company was looking into ways to update its lines. A memo dated December 14, 1900, addressed to J. B. Cooker, Esq. of the Everett Railway & Electric Company (it is unclear if this is an error or brief name change) outlined recommendations for improvements. Suggestions included moving the power station and car barn to the river side of Everett; increasing service to coincide with arrivals of Great Northern trains and steamships; upgrading the tracks to heavier rails; rebuilding the roadbeds; repairing or replacing many of the cars deemed to be in poor condition; and reconstructing the line from Bond to the Monte Cristo Hotel, a route that was described as being so curvy and steep as to be very dangerous.

In 1901, after riding out financial panic, John T. McChesney (1857-1922) stepped in and bought the controlling stock of the Everett Railway & Light Company. McChesney was an investor recruited by James J. Hill to go to Everett and get involved in the city's next wave of economic development. McChesney's early efforts were aimed at improving the light and water services, but his attention soon turned to the streetcar system. It seems clear that McChesney may have been working from the 1900 memo, because his moves followed most of the recommendations. To finance this work, Everett's streetcar lines, and its light and power system, were mortgaged on November 16, 1901, to the Manhattan Trust Co. of New York for a sum of $1,000,000 -- money that was never fully repaid.

First, the old strap-iron street rails used to construct the system were replaced with more modern 60-pound T rails. In March 1901, McChesney announced that a new power station for the line would be built on Bond Street, running at 1,400 horsepower. Lines would be expanded to offer improved service, being mindful of keeping the number of necessary transfers down.

Between 1901 and 1905 the track system was expanded to include a loop that included the Bond street train station, up Kromer Avenue to the Monte Cristo hotel, where waiting passengers banged a gong to hail the nearest car; a single line on Colby Avenue between 22nd Street and 37th Street; a second track added to busy Hewitt Avenue from Broadway to Chestnut Street; a crosstown line extension to Washington Street via Chestnut Street and Everett Avenue; Hewitt Avenue tracks over the new Great Northern viaduct; a new Colby Avenue loop around 19th and 37th streets; a crosstown line Summit Avenue extension; and tracks for a Snohomish Interurban line that began service on December 1, 1903. Between 1901 and 1903, all cars in operation were either refurbished, scrapped and cannibalized for parts, or completely replaced. McChesney would go on to run the Everett Improvement Company, which had purchased all the holdings of the Everett Land Company from receivership.

Organizational Changes

On February 23, 1905, a meeting was held in Wilmington, Delaware, to discuss the consolidation of the water, light, and streetcar service in Everett. The new company was incorporated as the Everett Railway, Light & Water Co. under the laws of the State of Delaware on March 10, 1905, with J. F. Reardon taking control of streetcar operations as superintendent. Shares of stock in the new company were subscribed to by Henry P. Scott, John T. McChesney, Edward C. Mony, who was secretary of the new company, L. S. Duryee, and Wyatt J. Rucker. From this point on control of stock in the companies was increasingly dominated by outside investors.

In 1907 all properties of the Everett Railway, Light & Water Co. were leased for a term of 999 years to the Puget Sound International Railway & Power Co., a corporation controlled by the electrical engineering consultant firm Stone & Webster. Engineering consultants is a modest title for two individuals, Charles A. Stone (b. 1867) and Edwin S. Webster (1867-1950), who methodically acquired or assumed control of an impressive number of street railway and utility companies across the United States with the backing of East Coast investors. A 1913 United States Internal Revenue income tax form listing all common stockholders showed that out of 20,000 shares, only 5,858 were held by Everett residents or corporations: the Everett Improvement company (44), J. A. Coleman (3), L. S. Duryee (3), J. T. McChesney (5,676), and Edward C. Mony (132). By 1917, Stone & Webster had absorbed all the stock of William F. Brown into its holdings.

In the midst of all these organizational changes, the Everett to Seattle Interurban line was constructed. The first train from Everett to Seattle made its morning run at 5:30 a.m. on Monday, May 2, 1910, just two days after James J. Hill passed through Everett to survey improvements that had been made to the Great Northern's lines and facilities. The Interurban served Everett until 1939. During its long run, the line worked collaboratively with Everett's streetcar system, leasing tracks from Everett, while Everett often leased cars from the Interurban. A January 1911 contract between the two companies even outlined a system for the Everett line to collect revenue from the Interurban passenger and freight cars passing through city limits on Everett streetcar infrastructure.

The Arrival of Car Culture

Things ran on quietly with Everett's streetcar lines until the 1920s, when Americans turned to the automobile. The first car arrived in Everett in 1902, but the adoption of cars as a primary mode of transportation was hampered by the slow development of paved roads, filling stations, and other infrastructure needed to make car travel practical and reliable. The first gravel roads in Snohomish County only arrived in 1901, and the first paved roads did not arrive until 1912. Despite repeated efforts at the local and state level, progress was gradual in gaining the funding needed to do any widespread improvements of Snohomish County roadways. Eventually enough automobile-friendly routes became available for local motorists to use to move around the county, and car fever took hold.

By 1923 the Herald was full of articles and advertisements related to cars. Every Sunday there was a three-to-four-page feature strictly devoted to car news. Coverage of the cessation of the streetcar service was sparse, as the shift from public transit to private car ownership appeared to be gradual. On April 6, 1923, the Herald ran an article announcing that the last streetcar run in downtown Everett had been made the day before. This hindsight notice of the end of an era had a "good riddance" tone, as if banishing something that was a nuisance to motorists. In an era increasingly dominated by the autonomy afforded by automobiles, the streetcars and their fixed tracks were in the way of progress.

The last line to disappear serviced Lowell and Delta, mainly for the convenience of the workers at Weyerhaeuser mills B and C; this soon went the way of its counterparts, replaced by autobuses.

End of the Line

In their heyday, Everett's streetcars were viewed as a great convenience for workers who commuted from residential areas to Everett's different industries, and for families who needed to travel from neighborhoods to the commercial centers of Everett. When they were first established, the streetcar lines helped passengers zoom up steep grades and past muddy, stump-filled fields. They were a virtually weather-proof conveyance to work, school, home, and entertainment. Near the end, they were slowing down traffic, and the rails were jostling the motorists who drove over them.

Not much remains to remind one of Everett's streetcars. Many of the rails were removed and scrapped in 1923 and more of them later, in 1942, to aid defense efforts. Revenue from the 1942 scrapping went to fund a Works Progress Administration project to resurface the streets from which the rails were removed. Past removals were only partial, and different City of Everett Public Works projects over the years have exposed occasional stretches of buried rails beneath the modern streets. In 1954 the stately brick power station on Bond Street was destroyed by fire. The last aboveground evidence of Everett's streetcar past can be seen on the northwest corner of Pacific and Colby avenues, where the old combined Interurban and Everett streetcar building still stands mostly vacant, awaiting a new purpose.