On May 5, 1942, the United States War Defense Command announces the forced removal of Japanese and Japanese-American families from Exclusion Area No. 39, a large semi-rural region of King County, Washington, between the Seattle city line and the Green River and extending west to the Kittitas County line. The region includes the towns of Renton, Tukwila, and Kent, as well as many smaller farming communities. Civilian Exclusion Order No. 39 is one of 108 staggered orders issued throughout the spring of 1942 in response to the attack on Pearl Harbor and President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066. In the Renton area, a number of the families affected are horticulturists, raising flowers and vegetables in nurseries and greenhouses.

A Growing Community

Japanese immigrants and their children in the first half of the twentieth century were deeply involved with agricultural pursuits throughout Puget Sound. From the Sand Point area of Seattle to Bellevue to the Green River, White River, and Cedar River watersheds, Japanese families took up vegetable and dairy farming. In the more urbanized Renton area, a number of Japanese turned to growing flowers and ornamental plants in greenhouses, in addition to vegetables. In the 1920s and '30s, the Iwasaki family, with 11 children, operated the Bryn Mawr Greenhouse and 17 acres; the Maekawas (sometimes spelled Mayakawa), had a nursery nearby. George (b. 1906) and Ichino "Irene" Kawachi (1914-2010) founded the Floralcrest Greenhouse in Skyway, specializing in new varieties of poinsettias. The Manos called their business the Earlington Greenhouses after the westside hill where it was located. As a young man Robert Mizukami (1922-2010) learned the trade from the Hirai family at their Maplewood Gardens along the Cedar River east of Renton; he went on to establish a greenhouse of his own in Fife and to serve as mayor of that town. The Nakashima family ran the popular Renton Greenhouse and Florist shop in downtown Renton. And just over the Seattle city line, in the Rainier Beach area, Fujitaro Kubota (1879-1973) began laying the groundwork for his famous garden, nursery, and landscaping business.

Subtle and not-so-subtle racism existed throughout this period; however, by and large, the Japanese families in Renton lived in relative harmony with their Caucasian neighbors. Children attended the same schools and played together. The older generation had more difficulty fitting in, largely due to language barriers.

The younger generation (Nisei) was expected to help out with the family businesses, working in the nurseries and helping truck produce up to Seattle for sale at the Pike Place Market or to brokers. Unlike the larger vegetable farms in the outlying areas, which shipped some of their produce out of the area by train, the nurseries sold locally.

The Japanese families maintained close ties with one another, socializing at cultural associations and religious events. The Japanese Greenhousemen's Association, founded in the late 1920s, provided networking as well as social occasions such as picnics.

War Clouds

The coming of war with Japan shattered the social dynamic in Renton and elsewhere. Families in the relatively unobtrusive business of raising vegetables and flowers for the public suddenly found themselves in the crosshairs of suspicion. Racism triumphed as many called for the immediate ouster of all ethnic Japanese from West Coast communities. An editorial in the Renton Chronicle railed in hateful and sarcastic terms against the possibility of a delayed evacuation to accommodate Japanese growers:

"A news story in a Seattle paper yesterday morning outlined the new 'plan' -- to keep the Japs raising cabbage as usual within a stone's throw of many defense plants ... Now that's very nice and thoughtful of the produce exchange, the seed merchants and those boys holding the notes and mortgages of the Japanese. If and when the signals of the local Japs bring a cloud of bombers on us from Japan, the Nips will be moved. But until the bombs begin to fall, profits as usual from the lettuce and the cauliflower and new, fresh arrogance from the insolent Japs in our midst!" (McGovern).

The 'Evacuation'

The exclusion order had been long expected; however, once it came down, events unspooled with lightning speed. Japanese and Japanese Americans (the edicts made no differentiation) in Area 39 were to register within two days at the Lonely Acres Skating Rink in a park (long gone to make way for Interstate 405) on the border between Renton and Tukwila, dubbed the Renton Junction Civil Control Station. About 1,000 individuals in the zone were affected.

This was only step one. Families were then given only a few days to wind up their affairs and dispose of their property before reporting to the Renton Depot on March 11 for the long train ride to the Pinedale Assembly Center, near Fresno. (Evacuees from Seattle were taken to the Puyallup Assembly Center.) From there they would be dispersed to various "relocation centers," sometimes referred to as "internment camps," or, even more euphemistically, "projects." Here they would wait out the war.

The Hirai Family

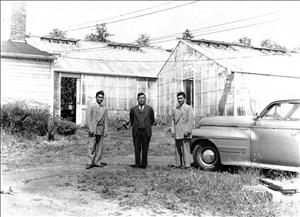

On the east side of the Renton area, in the Cedar River Valley, the Hirai family operated a greenhouse called Maplewood Gardens located just across the highway from the Maplewood Golf Course. The seven children of Gisuke (1887-1983) and Tami Hirai (1891-1945) helped raise vegetables and flowers which they took to Seattle by truck to sell. The nursery also provided landscaping plants for the golf course. Two other Japanese families raised vegetables in the same area, the Mizukamis and Serizawas.

Bob Aliment (1931-2019), son of golf course manager and later Renton Mayor Frank Aliment (1908-1976), played with some of the Hirai children. Burned into his memory is an incident in which he and young Fred Hirai doubled up on a bike; the inevitable crash left Bob with a damaged knee which had to be treated at Renton's Bronson Memorial Hospital. To his chagrin, the doctor took the opportunity to remove his tonsils.

The disruptions occasioned by the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, hit the Hirai family hard and fast. Before the next day dawned, father Gisuke Hirai had been arrested, swept up in the FBI's initial response to the crisis. That agency had kept watchful eyes on a number of suspected enemy agents for some time. Many of these were targeted simply for being part of Japanese cultural associations. In a time of paranoia, it wasn't long before rumors ran rampant. Bob Aliment, 9 years old at the time, recalls lurid stories of the Hirai family collecting money from the Japanese community and smuggling it over to Japan by the suitcase-full:

"I'll tell you, when the war broke out on December 7th -- on the 8th, three fellows came into Maplewood Golf Course and wanted to see Frank Aliment. That was my father. He was the manager. They said, we're from the FBI and we're here wanting to know what you know about the Hirai family. And my dad said, well, the only thing I can really tell you -- The man and wife never spoke English, so I have nothing to do with them. But the kids, a couple of them worked on the golf course and they caddied and my son went to school with a couple of them. And they said, well, we'll tell you something: The old man [Gisuke Hirai] had a shortwave [radio]. He knew exactly what was gonna happen" (Aliment).

Gisuke Hirai, along with several other suspects, were taken to the immigration center in Seattle on Airport Way and interrogated. After three weeks, they were shipped off to Fort Missoula, Montana, where they were held for six months before being allowed to rejoin their families -- at another concentration camp.

Declassified documents from the Department of Justice show that the FBI relied on informants to build their case against Hirai and other "enemy aliens." A number of patriotic-minded Americans had called or written to provide vague evidence. One woman recalled a conversation she had had with Gisuke's wife, Tami, more than two years prior to the February 1942 hearings in which Mrs. Hirai had told her that her husband was visiting Japan and that she was pleased that two of her children were living in that country. In contrast, Frank Aliment provided an affidavit on behalf of Hirai: " ...affiant has always considered said Gisuke Hirai as a good resident of this country and believes that he has always raised his family -- all his children having been born in this country -- to be good, loyal American citizens" (Affidavit).

By that time the rest of the Hirai family had also been forced off the land they had tended for years. Neglect caused severe damage to the greenhouses. In addition, squatters had taken over the property. According to records of the Minidoka Relocation Center Legal Division, son Roy Hirai appealed to authorities to help evict a man who "has not paid a single cent as rental" (Minidoka). Despite assurances of help, it does not appear that any action was taken.

Nor was this the only tragedy the family faced. Mother Tami had been released from Minidoka in 1944 directly to a mental health facility in Blackfoot, Idaho. She was subsequently transferred to Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington, where she passed away a year later. It is likely that the strain of incarceration contributed to her death at 54.

Roy and Gisuke were able to establish a greenhouse in Kent after the war. In 1954, after passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, Gisuke Hirai applied for U.S. citizenship, something that had been denied him and other Issei (Japanese immigrants) until that time.

The Manos

Meanwhile, on the west side of Renton, the Mano family established a more enduring institution, the Earlington Greenhouses. Kikujiro (1896-1971) and Riki (b. 1903?) Mano immigrated from Japan about 1930 and leased a small greenhouse in the Bryn Mawr neighborhood. A few years later, about 1937, they moved to the "sunny" side of the hill, a neighborhood called Earlington which was annexed to Renton in 2009. They were able to take possession of an existing nursery on a lease-purchase arrangement. Here they built a Dutch-style greenhouse, with large glass panels on sloped sides. With sons George (1930-2022) and Tosh (1928-2017) and daughter Kiyoko (b. 1926), they began by growing tomatoes and cucumbers in the greenhouse. Soon they added flowers and bedding plants outdoors. Easter lilies became a specialty.

In an oral history, George Mano does not recall any trouble with neighbors prior to the outbreak of war. As a child, he played with Caucasian neighbor children; together they built a basketball court in a vacant yard. However, after Pearl Harbor things changed quickly and drastically. George recalls the curfews that affected only Japanese, Italian, and German families, as well as the "No Japs" signs in shop windows. When the family had to pack up and leave, it was devastating. The nursery was just beginning to break even following the economic depression of the 1930s when they had to walk away, leaving it with a caretaker lessee.

The Return

As the war wound down, incarcerated Japanese were gradually released from confinement, most with a one-way train ticket and a small grant of cash to get them resettled. Many from the Renton area did not return, but chose to move closer to family in other parts of the country. Those who did often found their homes and businesses in shambles. For those in the horticulture industry, starting over meant more than replacing stolen equipment and repairing greenhouses. Crops had to be reestablished, supplies obtained, and customer bases rebuilt, all during a time of lingering resentment toward them. In 1991, George Kawachi described to a reporter the difficulty of picking up his business: "He started knocking on doors to sell his first crop -- 'all old friends,' he said. And the answer he heard: 'I can't buy your flowers, they'll boycott me'" (Ziebarth).

Unlike many other families, the Manos did return to the Renton area and were able to reclaim their business, after waiting for the caretaker's lease to run out. The family, at last, was able to purchase the property outright in the name of their oldest child, daughter Kiyoko. The Alien Land Laws, which prohibited Issei from owning land in the state, were not fully repealed until 1967. About 1950, son Tosh (1928-2017) and his wife, Tomi (1932-2018), took over management of the business and ran it until 1995. Looking to retire, the Manos sold the popular nursery to faithful customers Ron Minter and Paul Farrington, who ran it for another 20 years under the name of Minter's Earlington Greenhouse and Nursery.

In 2001, Tosh Mano spoke to students at Renton High School about his experiences during the war. Following the talk, he was presented with his high school diploma.

While some growers were able to resurrect their nurseries following incarceration, the heyday of small market growers was passing quickly. Squeezed by development and outpaced by large-scale commercial grow operations, many of the family-owned nurseries faded away. Today housing occupies the land of both the Hirais and the Manos.