Though important legal cases are not usually known by the name of the judge who decides them, this one is. "The Boldt Decision," as it is commonly referred to, was one of the biggest court decisions issued during the twentieth century involving Native rights. While the decision itself dealt with tribal fishing rights, its affirmation of tribal sovereignty was more far-reaching and represented a huge (and unexpected) victory for Native Americans.

The Right to Take Fish

Salmon and steelhead were a staple of the Native American diet in the Northwest in the millennia before the first non-Native settlers began arriving in the nineteenth century. These fish were found in such abundance that they not only provided enough food for Native needs but also were used to barter with other tribes and, later, fur trappers and early settlers who were passing through.

By the 1840s and 1850s, American settlers were moving into the Northwest. Congress created Washington Territory in 1853, and President Franklin Pierce (1804-1869) appointed Isaac Stevens (1818-1862) the territory's first governor. Stevens also was named Superintendent of Indian Affairs, with instructions to negotiate treaties with the territory's numerous Native tribes in order to move them to reservations, where the settlers planned to teach them how to farm and to assimilate them into what the settlers believed was the American way of life. This would open the rest of the territory for non-Native settlement. By late 1854, the Natives were left with less than 10 percent of their original holdings.

Stevens eventually entered into 10 treaties with the Natives, including the Treaty of Medicine Creek, which covered the lands around southern Puget Sound and its inlets, and the Treaty of Point Elliott, which covered central and northern Puget Sound and stretched north to the border with British North America (later Canada). The Natives showed a considerable flexibility in negotiating with the settlers, partly because they were not able to fully communicate with them. Different tribes spoke different languages, and when they communicated with the tribes the settlers typically used the Chinook Jargon, a pidgin trade language that was not only limited but also difficult to understand and translate.

There was one thing the Natives did not negotiate away, and that was their fishing rights. This was not an issue for the settlers, who at the time were more interested in farming and logging. Thus the treaties contained language affirming the Natives' fishing rights; both the Medicine Creek and Point Elliott treaties have identical language stating, "the right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations, is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory ... Provided, however, that they shall not take shellfish from any beds staked or cultivated by citizens."

The State Moves In

Initially, both sides honored the treaties. It would have been hard not to: For the next 20 or 25 years non-Native settlement in the territory was minimal, and the settlers who were there were not especially interested in fish. This began to change in the 1880s when settlement began to rapidly increase. Some of the new residents bought land that had previously been a Native fishing spot and fenced it off, making it inaccessible to the Natives. Even before Washington became a state in 1889, this issue was litigated in a territorial court. In the case of United States v. Taylor, decided in 1887, Washington's territorial supreme court affirmed the Natives' right to fish at an off-reservation location that had previously been an accustomed Native fishing ground, even if the land was subsequently purchased by a bona fide purchaser. But rather than being a definitive decision, it was merely a first shot in a series of legal skirmishes over most of the next century.

The development of fish canneries in the final two decades of the nineteenth century also changed the equation. By the early 1900s there were dozens of canneries in Washington state, and the increasingly sophisticated methods used by these large commercial operations to catch millions of fish far eclipsed anything that the Natives could catch. Then the state began applying state regulations to the Native fishing, as well as charging them fishing fees.

The Natives had little recourse but to pursue legal remedies in court. Over the next 75 years decisions were rendered by state and federal courts that favored both the Natives and the state, leaving a confusing trail of decisions on the issues of federal and state policy toward Native Americans and Native fishing rights. Sometimes a decision was influenced by the whims of the court, sometimes it was influenced by the prevailing public sentiment. For example, during the 1920s both the federal and state government were united in eliminating Natives as a special class of citizens. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, also known as the Snyder Act, reflects this sentiment. The act granted full U.S. citizenship to Native Americans, buttressing the non-Native argument (which was raised repeatedly in the following years) that it was no longer necessary to treat Natives as a protected class, and accordingly, no longer necessary to provide them special fishing rights.

To some extent, this sentiment changed during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Economic conditions became so dire that in 1933 the U.S. government began providing assistance to many struggling Americans under the auspices of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's (1882-1945) New Deal. In 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act -- for many years colloquially known as the Indian New Deal -- which provided for the return of certain surplus land to the Natives and encouraged Native power over its internal affairs.

Court Decisions and Fish-Ins

Nevertheless, many obstacles remained. Court decisions in the 1940s and 1950s continued to be mixed. In 1942, the United States Supreme Court found in Tulee v. Washington that Washington state could not charge Natives a fee for fishing in their usual and accustomed grounds. A 1957 decision by Washington state's supreme court in State of Washington v. Satiacum affirmed Native rights to fish in their usual and accustomed fishing grounds provided there was no threat to the "conservation" of fish, a buzz word used by the state as far back as the 1920s as an argument to regulate Native fishing rights. In 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court in Puyallup Tribe v. Department of Game of Washington held that the state could, in the interest of conservation, regulate Native fishing pursuant to the same standards applied to non-Natives.

The fallacy with the conservation argument was that it wasn't the Natives who were responsible for any issues with conservation. Commercial fishing in Washington continued to grow during the early and mid-twentieth century, and as noted above, these operations had the capacity to catch far more fish than the Natives ever could. By the early 1960s, the Natives were catching somewhere between 2 and 5 percent of the annual salmon and steelhead catch in Washington. At the same time, the state began more aggressively enforcing its conservation policies and began arresting Natives for off-reservation fishing.

It was 1963, a time when the burgeoning Black civil rights movement had the nation's attention. The Natives had not missed it, and they considered their own call to action. The formation of the Survival of the American Indian Society (SAIA) followed in early 1964. Sit-ins were a common method of protest in the civil rights demonstrations, and SAIA was quick to adopt its own version, the fish-in. A well-known early fish-in (organized by a smaller Native organization, the National Indian Youth Council) included actor Marlon Brando (1924-2004), who had no ties to the Natives but embraced their cause. Brando was arrested at a March 1964 fish-in on the Puyallup River but was quickly released without charge on orders of Pierce County Prosecuting Attorney John McCutcheon, who explained, "Brando's no fisherman ... We think this was just window dressing for the Indians' cause" ("Marlon Brando").

Frank's Landing on the Nisqually River was ground zero for many of the fish-ins. It was the home of Billy Frank Jr. (1931-2014), a Nisqually tribal member and one of the foremost leaders in the movement to enforce Native treaty rights. A series of fish-ins there in October 1965 became violent and brought more publicity to the growing movement, both pro and con. An extended fish-in at Frank's Landing three years later lasted more than six weeks, and included a few hippies (who fought officers attempting to arrest Native fisherman and were in turn arrested themselves) and at least one member of the Black Panther Party. The protests culminated in a pitched battle at a fishing camp on the Puyallup River on September 9, 1970, when Natives, Tacoma police, and state game officials fought with guns, knives, tear gas, and clubs.

The Boldt Decision

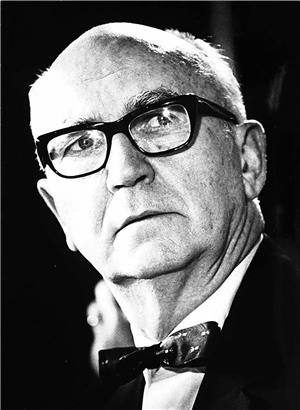

Watching the fracas from the banks of the Puyallup River that day was Stan Pitkin (1937-1981), U.S. Attorney for Western Washington. His office was already drafting a complaint designed to bring the fishing-rights issue to a head, and it was filed nine days later. The complaint, titled United States v. State of Washington, was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington on behalf of the United States, and as trustee for seven tribes, against the State of Washington. Another seven tribes later joined the action, and the Washington Department of Fisheries and other state agencies were later added as defendants. The case took nearly three years to wind through discovery and pre-trial motions before trial finally began in Tacoma on August 27, 1973, with Judge George Boldt (1903-1984) presiding. Forty-nine witnesses testified and 350 exhibits were admitted during the trial, which was held without a jury. It lasted for three weeks, six days a week, with no break for the Labor Day holiday. However, closing arguments in the case were not made until December.

Attorney General Slade Gorton (1928-2020), who later served as a U.S. Senator, represented the state. He later explained that the state's argument focused on the equal protection clause in the 14th Amendment, which he asserted should be applied to race, not treaty status. During the trial, the state argued that pursuant to the clause, Native Americans were not entitled to special rights to fish off-reservation. The state further argued that state regulations designed to control fishing were not discriminatory, despite evidence that the Natives were receiving only a small fraction of the total annual catch. The gist of the state's position was the treaties gave the Natives an equal right to fish, subject to reasonable state regulation -- not an equal right to 50 percent of the catch. The tribes argued that the state could not regulate their right to take fish at treaty locations, no matter the reason. The word "take" was key; it did not matter who caught the fish.

Boldt handed down his decision on February 12, 1974. First and foremost in his ruling was the nature and scope of the treaty fishing rights. Boldt reviewed the treaty wording closely, specifically the key language: "The right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations, is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory ..." and found that the tribes had the original rights to the fish, which they granted to the settlers, but this grant was limited. Boldt ruled that the language of the treaty provided for an equal sharing of the resource between the tribes and the settlers, and ruled that tribes that were parties to treaties (not all of the tribes in the state were) could take up to 50 percent of the fish harvest that passed through their recognized fishing grounds. This was to be calculated on a river-by-river, run-by-run basis. He rejected the state's argument that steelhead trout should not be included since they are not salmon, finding that the time the treaties were signed, the signatories considered steelhead no different than salmon.

Boldt also addressed the issue of whether Natives had any claim to fish bred in hatcheries, which did not exist when the treaties were entered into in the 1850s. The treaty language prevented Native taking of shellfish from beds maintained by non-Natives, but Boldt ruled that Natives could fish for hatchery-bred fish so long as they played a role in the breeding process. In an exclamation point to the decision, the judge ordered the state to limit fishing by non-Natives when necessary for conservation purposes. The decision was appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which affirmed it in 1975. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear a final appeal the following year.

Commercial and sports fishermen (and some non-Natives who were not fishermen) were furious. An effigy of Boldt was hung outside of the courthouse in Tacoma, while Boldt himself received "bales and bales of mail. Loathsome material," he told The New York Times in 1979 ("Remembering Boldt Decision ..."). Non-Natives protested the decision for years, while some commercial fishermen ignored the ruling and continued fishing as before. Similarly, the state initially sought to weaken the decision by attacking it with similar cases, but these efforts were not successful. To the contrary, the U.S. Supreme Court indirectly affirmed the Boldt decision in 1979 when it held in Washington v. Washington State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Association that the treaties provided the tribes the right to harvest a share of each run of fish passing through their fishing areas.

Boldt added more weight to his ruling by making the tribes co-managers of the state's fisheries. Neither side was prepared for this, and suddenly there were 19 tribes working with the state to manage Washington's fisheries. There were no plans for moving forward with a joint operation. In fact, there was no fish management plan in place in 1974 or even a reliable method of counting fish, despite the state's talk of conservation during the preceding half-century. Coming up with an accurate count was one of the first issues tackled by the new team, and aided by computer modeling, better fish-counting methods were developed. In turn, this led to an agreement on other management guidelines. It was an arduous effort that took about a decade to work through, but the state and tribes were eventually successful in creating a plan to move forward with jointly managing Washington's fisheries.