Everett High School captured the mythical national championship of high school football for 1920, claiming the title with a 16-7 victory over East Technical High School of Cleveland, Ohio, on January 1, 1921. In this original essay, Steve K. Bertrand -- an award-winning poet, historian, photographer, and longtime teacher and coach in the Everett School District -- writes about Everett's championship season, legendary coach Enoch Bagshaw, and the boys who made their mill town proud.

Tough Kids in Cleats

They were the sons of fishermen, pastors, saloon owners, merchants, businessmen, mill workers and mill owners, the boys who played football at Everett High School under Coach Enoch "Baggy" Bagshaw in the fall of 1920. They weren't big, but the boys from "The School of Champions" were disciplined and really, really tough. They were also well coached. They had tied Scott High School of Toledo, Ohio, 7-7, the previous year to finish the season unbeaten and with a partial claim to the mythical U.S. high school football national championship. Now, they wanted to win a national title outright.

Some 35 boys gathered on Athletic Field for practice the first week of September 1920. Athletic Field was located in the Riverside Neighborhood of Everett, at 24th Street and Rainier Avenue, the site of the old North Junior High School, now North Middle School. It had been a portion of the old fairgrounds. For four months the boys climbed into their football togs and trotted up and down Athletic Field every afternoon following school for football practice.

Coach Bagshaw had told them the same thing he told every team he coached on the first day of practice — "If you wanna play football, you gotta bring your own practice gear!" And so, the boys' mothers went to work making practice gear for their sons. They stitched together leather helmets to protect the boys' heads. They sewed together sturdy practice jerseys and pants. They bought lace-up, leather walking boots, and had the local cobbler add spikes. There weren't any face guards. No pads. Yes, you had to be tough to play football in those days.

Coach "Baggy"

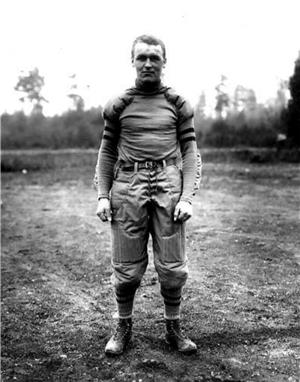

Enoch Williams "Baggy" Bagshaw was born on January 31, 1884, in Flint, Wales. He moved to Washington in 1892. His family settled on Seattle's Capitol Hill. He graduated from Broadway High School (known as Seattle High School) in 1903. Interested in becoming a mining engineer, Bagshaw enrolled in the University of Washington. He financed his education by delivering newspapers and milking cows. During his days at Washington, Bagshaw played football, just as he had done at Broadway High School. Short and 130 pounds, Bagshaw was a versatile player. A five-year starter and letterman, he played end, halfback and quarterback. He was also team captain. He graduated from the University of Washington in 1907. During this era, eligibility rules weren't quite so rigid. Bagshaw was the first of only two five-year lettermen in Huskies history. Of notable interest, Bagshaw is credited with throwing the first forward pass in school history during a game on October 10, 1906.

Following college, Bagshaw worked for a year as a Snohomish County engineer surveying roads. Then, he became a science teacher at Everett High School in 1909. Bagshaw was also given the duties of head football coach. Bagshaw served as a First Lieutenant with the 43rd Engineer Battalion of the United States Army during World War 1. Thus, he did not coach football in 1918. Following the war, he returned to Everett High School and resumed his duties as a teacher and coach.

His greatest gift was his ability to coach football. Bagshaw was dedicated. He lived the game. And, he expected his players to be the same way. A disciplinarian and perfectionist, Bagshaw often barked at his players. Neighbors had taken to closing their doors and windows during football practice to avoid hearing Bagshaw's tirades. He'd often push his players beyond what they thought they could do, shouting "Pick it up, kid!" "No slouching!" "Keep your rear down!" "You got this!" or "Take a lap!" His style of rough, tough football was well-suited to mill town. Bagshaw instilled a spirit in his players people noticed and liked. As a result, folks loved him. They called him "Baggy." But, on the football field, it was strictly business. It was "Coach Bagshaw." He didn't carry a clipboard, nor did he blow a whistle. But when Bagshaw spoke, people listened.

The Talk of the Town

Everett was still a relatively young town. It had been incorporated in 1893, the same year as the Panic of 1893. Also known as the "Silver Panic," the financial crisis closed shops, factories and banks. People left town. Still, it was Everett's toughness that helped it prevail. A theatre was built. The Everett Herald started. Houses sprung up. Saloons and churches were built. Everett's streets were named after wealthy investors such as Henry Hewitt, Charles Colby (the town is named after his son, Everett), John D. Rockefeller and Colgate Hoyt, who helped put Everett on the map. Another plus was the arrival of James J. Hill's Great Northern Railway in 1893. And, as the population quickly grew, mills sprung up along the bayside and riverside. People called Everett the "Pittsburgh of the West." Folks bragged it was the lumber capital of the world.

A raw town, Everett was often at odds with itself. Mill owners and mill workers didn't always see eye to eye. There were frequent strikes. These rising tensions would lead to "Bloody Sunday," or "The Everett Massacre," which took place on Sunday, November 5, 1916. The battle between local authorities and the Industrial Workers of the World (called "Wobblies") left seven dead on Everett's City Dock. In 1920, The Everett Massacre, like the Spanish flu, lingered in the streets of Everett. Still, Bagshaw had a way about him. A healer and inspirer, he brought the community together around football. Yes, people could definitely agree on one thing: Everett had a darn good football team. Rich or poor, Baggy and his boys were the talk of the town.

Baggy's boys practiced until dark, passing, punting, kicking, blocking, tackling, and running. They did lots of pushups too. Sometimes, if practice didn't go quite to Bagshaw's liking, the boys ran the hill from Athletic Field to the high school. Rainier to Colby. Back and forth. Again and again. No rest. The clatter of cleats and labored breathing under the street lights after dark before heading home to dinner. Coach Bagshaw worked the boys hard. He wanted them ready for the strenuous season ahead. Over the next couple of weeks, he whipped the boys into shape.

Bagshaw knew he had a promising team with veteran lettermen from the 1919 squad including Les Sherman (captain/fullback), Carl "Mickey" Michel (halfback), Glenn "Scoop" Carlson (quarterback), Ed Manning (halfback), George "Windy" Wilson (halfback), Chalmer "Brute" Walters (center), Ray "YMCA" Witham (guard), Fred Westrom (end), Merle "Pete" Dixon (end), Roy "Peroxy" Sievers (end), Harold "Tubby" Britt (tackle), and Clarence "Clibbets" Torgeson (tackle). Plus, there were new players like Art Ingham (guard), Walt Morgan (halfback), and George Guttormson (substitute quarterback).

As summer waned, the day of the first game approached. And, with its approach, the Everett High School football team of 1920 set out on its pursuit to win the high school championship of the United States. A national championship. "We'll take it one game at a time, boys," said Coach Bagshaw.

Into the Season

The 1921 Everett High School yearbook, the Nesika, chronicles well the events of that glorious 2020 season. The first game was held on Monday, September 13. It was a preparatory game against the Everett High Alumni team made up of some of the best players who ever played football for Everett. Two of the boys had been stars on the 1919 co-champions. The two teams battled to a 13-13 tie. But, it was obvious to everyone gathered at Athletic Field that Coach Bagshaw had himself another championship-caliber team.

The next game was scheduled for Saturday, September 25, against Stanwood High School. But at the last minute, Stanwood backed out, so Sedro-Woolley agreed to come down and play Everett. For the first half, Bagshaw played his second team. But, during the second two quarters, he played his regular squad. In the end, Everett stomped Sedro-Woolley 68-0. The game drew a fair-sized crowd to Athletic Field. Interestingly, Sedro-Woolley would be the only Washington high school team Everett played in 1920.

In those days, Everett took on anyone who chose to challenge them in a football game. This included prep, college and military teams. And so, on Saturday, October 2, the Bremerton Navy Yard team traveled to Everett to play Baggy's boys. Bremerton was confident they could beat Everett. After all, Bremerton outweighed Everett seven pounds a man. They were also all over 21, as some of them had fought for Uncle Sam in World War 1. What chance did these teenagers have against grown men? The Naval commanding officer told his players not to play too rough against the boys. Therefore, it was quite a surprise to Bremerton when they got beat 27-0.

The following Saturday, October 9, another Naval team journeyed to Everett to take on Baggy's boys. They were the Bremerton Naval Base Hospital. They had recently beaten Bremerton Navy Yard by a score comparable to Everett. It looked to be a good matchup. However, with several second team men in the lineup, Everett sailed right through them. In the end, they notched a win over Naval Base Hospital by a score of 84-0. Baggy's boys even managed to score four touchdowns in the final six minutes of the game. Everett was running up such big scores, other teams didn't want to play them. Folks still spoke of the 170-0 drubbing Baggy's team had given Bellingham in 1913. In 1920, Chehalis cancelled its game against Everett.

Consequently, there was no game on Saturday, October 16, so the team traveled to Seattle to watch the University of Washington play the University of Montana. Prior to the game, Everett watched the University of Washington's freshmen squad play St. Martin's College. Everett had an interest in this game as it was scheduled to play both teams over the next two weeks.

The game against the University of Washington freshmen was played on Saturday, October 23. Again, they were playing a team with players much older than Baggy's boys. Furthermore, the UW freshmen were eager to play Everett. They wanted revenge. They had tied Everett 7-7 the previous year. It looked like Everett had finally met its match. But Coach Bagshaw had his boys ready. And, through the fight on Athletic Field, Everett prevailed 20-0. The local paper said, "The crack University team returned to Seattle a sadder but wiser eleven."

On Sunday, October 31, Everett faced St. Martin's College in a game that promised to be an exciting 60 minutes of football. Incidentally, Bagshaw insisted his boys play 15-minute collegiate quarters, instead of 12-minute high school quarters. Previously, St. Martin's had played the UW freshmen to a standstill. Everett had beaten the UW freshmen. St. Martin's College wanted to prove it was better than the UW frosh. The game was a tussle from beginning to end. There were several injuries. The Athletic Field was quite muddy. Roy Sievers, who played left end for Everett, had a brilliant game. However, he had to be taken out during the second half with a broken ankle. In the end, Everett sacked St. Martin's 19-0.

Because there was no game scheduled for Saturday, November 6, Everett again traveled to Seattle, this time to watch the Washington-Stanford game.

Then, on Saturday, November 13, The Dalles (Oregon) High School team traveled to Everett to try their luck against Baggy's boys. They were the reigning champions of Oregon. Newspapers were calling the game the "Interstate Championship." But luck was not with The Dalles team on Athletic Field that day. They made the long trip home after suffering a 90-7 dredging by Everett. Not counting the Alumni game, The Dalles was the first team to score a touchdown against Everett. With first-string quarterback Glenn Carlson on the sidelines, and second-string quarterback George Guttormson sitting out as well, 115-pound Chuck Drysdale substituted as quarterback. The crowd that autumn afternoon went home thinking there was no beating Baggy's boys. The newspapers praised Everett's powerful play, stunning attacks, and brilliant victories. A powerful team offensively and defensively, Everett had established itself as the strongest prep school eleven in the Northwest. Folks referred to them reverently as "the pride of Washington."

Conquering the Western States

After The Dalles victory, Everett was hungry to face teams from other states. But Bagshaw wasn't about to let his players get big heads. In order to get a better idea of his competition, he scheduled a game with East High School of Salt Lake City, Utah, for Thursday, November 25. He even gave the Salt Lake City team $2,500 to help with expenses. East High School was a formidable foe in this Thanksgiving Day game. For the past three years, they had claimed the state championship in Utah. But of all the East High School teams, rumor had it this was their best. They were known as a "speedy eleven." They simply ran right through opponents. The Utah team played hard. But Baggy's boys played harder. When the 60-minute whistle blew at Athletic Field, Everett had upended the East High team by a score of 67-0.

Next came a challenge from Long Beach, California. They were feared throughout Southern California. Long Beach had defeated opponents by similar lopsided scores as Baggy's boys. It promised to be a hard-fought battle. The game was played in California on Friday, December 17. Faculty manager John Corbally worked out the details for the trip. After a big sendoff from the hometown fans at the Great Northern Train Depot down on Bond Street, Everett headed south with just 12 players. They arrived in Los Angeles a few days early. This gave them time to prepare for the game. Because Bagshaw didn't trust the quality of water in California, Everett brought along its own barrels of water. Team managers Reynolds "Tuffy" Durand and Anders Anderson rolled the wooden barrels of water off the train.

Long Beach declared the day of the game a half holiday. This drew a crowd of 15,000 strong to the game. The game was played on the Long Beach campus, where new stadium grandstands had been constructed. Long Beach players watched the Everett players warming up in their shoddy uniforms before the game and laughed. But it was Baggy's boys who got the last laugh. Calling no timeouts, they lumbered over Long Beach by a score of 28-0. The Long Beach Jackrabbits couldn't do much against Everett's aggressive defense. Actually, they were outplayed in every aspect of the game. Leslie Sherman and George Wilson led the Everett team offensively. Glenn "Scoop" Carlson had a great passing game at quarterback. Merle Dixon, Carl Michel, and Fred Westrom caught most of the flying pigskins. Sherman and Wilson intercepted Long Beach passes. Coach Bagshaw, not happy with penalties against his team, did his share of crabbing at officials. Many mill town fans made the long trip to California to watch Baggy's boys. Those not in attendance gathered in the Everett High School auditorium and Rose Theatre awaiting the score. When the telegraphic report from the "City of Angels" came over the wire that Baggy's boys had won the Western United States Championship, they cheered loudly. Yes, if the angels were smiling on anyone that day, it was Everett's football team!

A Challenger From the East

Visitors had been stunned by Everett's powerful play throughout the fall, as it racked up victory upon victory. Even schools in the Midwest and on the East Coast had heard of Everett. They were eager for a game. East Technical High School of Cleveland, Ohio, offered the challenge. When Coach Bagshaw heard of East Technical's challenge, he simply said, "Bring em on." Local historian Larry O'Donnell stated, "Ohio was a hotbed of high school football from 1912 to 1937. The national championship was won or tied 10 times by teams from Ohio. Scott High School of Toledo, which tied with Everett 7 to 7 on January 1, 1920, either won or shared the national title four times during that era. One reason Everett wanted to play East Technical on January 1, 1921, is that East Tech had closed their 1920 season with a victory over Scott."

And so, with an undefeated record, Baggy's boys headed into a game for the mythical championship of the United States. The game was held at Athletic Field in Everett at noon on Saturday, January 1, 1921. Many of the 30,000 residents of mill town were gathered at Athletic Field that crisp New Year's Day. It was said 10,000 attended. The game had sold out quickly. The wooden grandstands on the east side of the field were packed. Spectators crowded around the football field. They had come by foot, trolley and Model T.

East Tech coach Sam Willaman and his squad of 20 strong were known for their strong line, speedy backfield, and great teamwork. It was an interesting matchup. The Cleveland team proved dangerous with the forward pass; while "the Everett team specialized in straight football without the trimmings," stated the 1921 Everett Nesika.

Larry O'Donnell researched one of the East Technical players. He noted: "Jack Trice was a tackle for East Technical. An exceptional player, he was the only African-American player on either team. Following high school, Trice followed his coach to Ames, Iowa, where Willaman had been named the head football coach at Iowa State College (now University). In 1997, the football stadium at Iowa State University was formally dedicated Jack Trice Stadium. It became the first Division 1 school to name its football stadium after an African-American athlete."

Playing halfback for Everett, Carl Michel had a great game picking holes and returning punts. Though Everett's play at times was rather ragged, they finally got down to business and plowed holes through the Cleveland line for critical gains. Cleveland made frequent substitutions during the game. Everett played its starting eleven. It was a see-saw battle. A game of gridiron grit. The crowd cheered loudly. A large, gray gull circled over Athletic Field. Actually, this was the fourth game at which a gull had put in an appearance. The Daily Herald's Zac Hereth noted, "Everett's victory was the result of a gritty style of football that would be hardly recognizable today. With quarterback Glenn Carlson, fullback Lester Sherman and running backs George Wilson and Carl Michel leading the offense, Everett churned out 365 rushing yards on a whopping 76 carries, largely on runs between the tackles. Just eight passes were thrown." And, in the end, Everett won; it had beaten Cleveland by a score of 16-7. Baggy's boys had done it -- they had won the national championship!

When the game ended, Everett fans cheered, hugged one another, tossed hats into the air, and then rushed onto the field to congratulate Coach Bagshaw and his boys. Throughout mill town, church bells rang, mill whistles blew, and tugboats tooted their horns. Drinks were on the house in local saloons. Winning was a proud moment for everyone.

Now, following the game, people spoke of the seagull that had been spotted circling over Athletic Field. It had hovered overhead throughout the game. As mentioned, a gull had been noticed at three previous games. Folks believed it was an omen of good luck. Word spread throughout town. Seagulls became a symbol of victory. The student body of Everett High School mounted a large, stuffed gull in the school's trophy case as an emblem of victory. It was nicknamed "Old Faithful." Shortly thereafter, Everett High School adopted the seagull as its mascot. From that day forward, the "School of Champions" has been known as the Everett Seagulls.

Epilogue

From 1911 to 1920, known as the "Bagshaw Years," Everett lost only one game, and that was by a single point, a 13-12 loss to Hoquiam in 1915. Hoquiam was good. Still, Everett got revenge the next year beating Hoquiam 32-0. During the Bagshaw years, Everett outscored its opponents 3,001-375. Bagshaw's 1919 and 1920 teams claimed national championships. But the foundation for these teams was built upon the success of his earlier squads. Football historian Tim Hudak rates Everett the sixth best high school football program in the country during the twentieth century.

Furthermore, Larry O'Donnell notes, "Under Coach Bagshaw, football became a 'civic unifier' in Everett, a rough, tough mill town where lumber management and workers were frequently at war with each other." Whether you were a member of the haves or have-nots, football was well-suited to blue collar Everett. The success of Bagshaw led to him being hired as head football coach at the University of Washington. And, like Everett High School, Bagshaw turned the University of Washington football program into a powerhouse. In nine seasons, the Huskies compiled a record of 63-22-6. Bagshaw took teams to the Rose Bowl in 1924 (tied Navy 14-14) and 1926 (lost to Alabama 20-19).

Bagshaw was the first former UW player to be hired as the program's head coach. Nine of his Everett players followed him to the UW, including the likes of George Wilson (All-American), Abe Wilson, Fred Westrom, George Guttormson, Roy Sievers, Leslie Sherman (All-American), and Chalmer Walters. George Wilson would be rated the greatest player in the first 50 years of UW football history. It was said he could run 100 yards in 10.3 seconds wearing tennis shoes.

Bagshaw announced his retirement as UW coach on October 23, 1929, to be effective at the season's end. It had been a challenging season on and off the field. Folks respected Bagshaw, but didn't necessarily love him. He wasn't unemployed very long. Governor Roland Hartley, an Everett lumber baron, appointed him Supervisor of Transportation in the State Department of Public Works, on March 24, 1930. Bagshaw collapsed and died of a heart attack at the "Old Capitol Building" in Olympia on October 3, 1930. He was 46. Stanford coach Pop Warner said, "I was shocked and grieved to learn of my friend Bagshaw's untimely death. He was a square shooter, loyal friend, and a real sportsman."

Everett's Athletic Field was renamed Bagshaw Field at halftime of a game on November 26, 1931. The placard located in the northeast corner of Bagshaw Field was dedicated on November 8, 1985. Bagshaw's son, Bob, and daughter, Margaret, unveiled the monument. Chalmer Walters and Roy Sievers, players from the 1920 championship team, were speakers, as was longtime Everett coach and athletic director Jim Ennis. Bagshaw was inducted into the Husky Hall of Fame in 1980. He is buried in Seattle's Lake View Cemetery.