On January 1, 1921, members of Everett's Black community host a dinner party for visiting high school football star John "Jack" Trice (1902-1923), an acclaimed tackle at Cleveland East Technical High School. Trice, 18, and his teammates have journeyed by train from Ohio to play Everett High School in the New Year's Day national championship game held that same morning. Trice is the only Black player on either team. The party, at the Everett home of George Samuels, is co-hosted by Samuels' nephew, J. Wesley Samuels. Trice will die less than three years later from injuries sustained in a football game during his sophomore year at Iowa State University.

Laying Plans for a National Championship

After Everett High School's football team completed an unstoppable 1920 season, defeating all comers from Washington and continuing its successful campaign into California, it was unclear if the squad would get another chance to play. On December 20, as Everett's players and coaching staff were making their way home by train from Santa Barbara, California, communications from coach Enoch Bagshaw in the Everett Daily Herald attempted to prepare Everett fans to be disappointed. But a few days later, it was confirmed that Everett would indeed compete again, playing host to East Technical High School of Cleveland, Ohio, on New Year's Day in a battle for the mythical national championship of high school football.

A citizens committee met to investigate ways to expand the seating at Athletic Field, later renamed Bagshaw Field, from 5,000 to 10,000 or greater. A maximum price of $3 per ticket was fixed. It was planned that proceeds from ticket sales would go to erect new bleachers, locker rooms, and caretaker facilities. A proposal was made to purchase additional land next to the fields for this purpose. Tickets for the grandstand sold out within an hour, and sales for other seats were brisk.

As Cleveland's East Technical squad made its way west by rail, the team's strengths were dissected in almost daily pieces in the Everett Daily Herald. Their style of play was said to be a "second edition of Ohio State University. Speed and forward passing" were relied on heavily ("East Tech Depends ..."). Another story claimed that the average weight of Tech players was 152 pounds, noting that the average was brought down by the presence of their 125-pound quarterback. East Tech had scored 462 points in 10 games and looked to be a strong challenger to the Everett eleven.

Everett was abuzz with anticipation for the return of its heroes from their California conquests, and the arrival of the Eastern challengers. Local organizations began planning celebrations for the home and visiting teams. The Everett Aerie of Eagles proposed an evening of entertainment on the night before the big game, and dances and dinners were planned for after the competition. Also in motion, though not mentioned by the local press, were plans being made by Everett's Black residents to celebrate a specific member of the East Tech eleven: John "Jack" Trice.

John "Jack" Trice

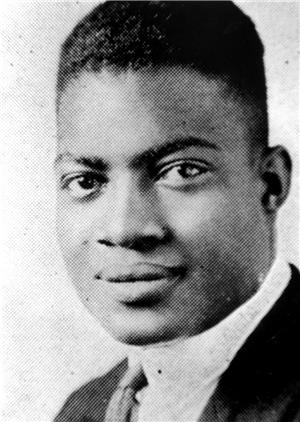

Jack Trice was an 18-yeer-old right tackle who was enjoying a tremendous season. Led by coach Sam Willaman (1890-1935), a former star for Ohio State, Trice's team had steamrolled the competition to an undefeated record, outscoring opponents by nearly 44 points per game. In one notable game versus Longwood, East Tech racked up a 120-0 shutout. Trice played an important role at right tackle; weighing in at 168 pounds, it was his job to open a hole for the running back on offensive plays. In a 1979 interview, Trice's former teammate Johnny Behm recalled that, "no better tackle ever played high school ball in Cleveland. He had speed, strength and smartness" (The Life and Legacy of Jack Trice).

At the time of Trice's visit to Everett, he was the only Black player on either team vying for national championship glory. His visit caused excitement for local Black residents, likely because of his national success, but also because he was the first Black athlete to compete in an Everett High School football game. To date [2021] there has been no evidence that any other Everett High School sporting events had been integrated before Trice's arrival.

Game Day

Game day held a packed schedule for Trice and his teammates. After staying in Seattle, they made their way to Everett by train, and then took the Smelter streetcar to reach Athletic Field. Crowds of spectators lined up outside before the doors opened at 10 a.m., hoping to take their seats before the cutoff just before noon: There would be no further entry after kickoff, until time was called at the end of the first quarter. The Elks band played a lively program of popular marches to keep the gathering crowd entertained. As the teams took the field, each was greeted by roars and thunderous applause.

When the competition began, it was remarked in the Herald that the players appeared very nervous. The nerves would continue through the second quarter, until everyone settled in and began to play in earnest. Eventually, Everett High wore down the visitors and claimed a 16-7 victory. Trice's actions on the field were frequently mentioned in the Herald's play-by-play coverage. He received a special acknowledgement in the telling of a quick anecdote about a young boy who snuck down to give him an encouraging gift: "The Cleveland team evidently has some real fans in the stand. During the rest period a little colored boy who said his name was Bill Davis cautiously advanced to the Cleveland team and slipped right Tackle Trice, the big colored linesman of East Tech, a chocolate bar. He turned and ran like a scared rabbit" ("Bagshaw's Eleven Forges..."). The lad was likely William A. Davis, a resident of Everett who would have been about 12 at the time.

Played in front of an estimated crowd of 11,000 spectators from around the region, the competition was an exciting kickoff for 1921. As the crowd slowly dispersed, the tired athletes were given little time to relax before being whisked off to celebrations.

Celebrations

After the excitement of the game, the people of Everett were ready to celebrate the home team as well as their visiting challengers. There was a banquet held in their honor at Weiser's Cafe at 1617 Hewitt Avenue, where representatives of each team, including the coaches, toasted the players on each side. It is unclear if Trice attended this event, but it seems doubtful. In an article published after the Cleveland team had long departed from Everett, it appears that there were separate events planned on the same evening to celebrate Trice. Whether this was because he was not welcome at the main events, or because the Black community of Everett wanted to celebrate him individually, remains open to interpretation. Accounts from Trice's college teammates mention that he was frequently not allowed in places where the team ate or lodged, but no accounts could be found covering his travels with his high school team.

The evening's celebrations started with a dinner held at the home of George and Rosie Samuels. Hosting the event was their nephew, Wesley Samuels (1891-1954), as well as Aurelius Davis (1884-1951), and Robert Rischarde. In attendance were Wesley's parents, John and Jennie Samuels, active civic organizers in Everett, as well as numerous local and out-of-town guests. After dinner several musical pieces were performed and enjoyed by the guests.

After being fed and entertained at the Samuels residence, Trice was escorted to a dance given at the Independent Order of Oddfellows Hall on Wetmore. The evening appeared to be a joyous one, and despite what must have been a disappointing loss on the field, Trice's visit seemed to have left a favorable impression. In a speech given at the dance, he stated that, "he liked the West and especially Everett, where he had been so well entertained, and that he hoped to return to the coast to live" ("Honor Negro Player..."). Before leaving, Trice was presented a 1921 Everett High School pennant as a souvenir. Local fans and out-of-town guests accompanied him to the train station to bid him farewell, treating him to a number of high school yells.

A Tragic End

Trice never did return to the West. After graduating from high school, he followed Coach Willaman and five of his East Tech teammates to Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa. There he excelled in track and field in addition to football, and was a strong student with an interest in animal husbandry. It was his desire to learn modern techniques that he could take to the South to help Black sharecroppers. In his sophomore year Trice made the varsity football squad. In his second game, played on October 6, 1923 against the University of Minnesota, he was trampled during a play. He was taken to a nearby hospital where he was accurately diagnosed with a broken collarbone and given clearance to travel back to Iowa. But doctors had failed to recognize that Trice was bleeding internally. Within two days of the game, he was dead. He left behind his young wife, Cora Mae (1907-1993), whom he had married months earlier over summer break.

Trice was immediately mourned at Iowa State University. Officials suspended classes, and several thousand students gathered to pay their respects. Teammates carried his casket and set it on a platform near where speeches were given in his honor. Fundraisers were held to pay for his funeral expenses, and to aid his wife and his mother. In Everett, his death was marked by a brief notice in the Herald the day after his death. A longer piece ran on October 10, noting that Trice had played in Everett the year prior, and that he had been considered one of the best tackles in the West.

Years after his death, witnesses remained divided over whether Trice's injuries were deliberate or accidental. Iowa State refused to play the University of Minnesota again until 1989. Meanwhile, Trice's name had almost slipped into obscurity by 1957, when a student working in a school gymnasium found a plaque that Trice's teammates had commissioned in 1924. That discovery sparked a slow movement among the student body to recognize Trice's legacy. A long period of struggle and protest for racial equality on the Iowa State campus throughout the 1960s and 1970s kept his story alive within the student body consciousness. As a result of persistent student and community activism, Iowa State honored Trice with the naming of the Jack Trice Resource Center (a library), and in 1997, by renaming Cyclone Stadium as Jack Trice Stadium. Additionally, a bronze statue of Trice appears on campus. The rediscovered plaque contains a letter Trice wrote in his hotel room on the eve of his fatal game against Minnesota. His letter began:

"To whom it may concern:

My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life. The honor of my race, family, and self are at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body and soul are to be thrown recklessly about on the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped will be trying to do more than my part" ("Letter by Iowa State ...").

Trice didn't live long enough to fulfill his full promise in life, but he undoubtedly left an important legacy for his race, family, and self. His tragic story inspired the fight for Black equality in generations of students on the Iowa State campus, but long before that, he brought together an excited community of Black people from the Puget Sound region, eager to celebrate his success.