On July 18, 1897, one day after the Klondike gold rush begins in earnest when the steamship Portland docks at Seattle carrying 68 miners and two tons of gold lifted from the Klondike River, an advertisement for Seattle merchant Cooper & Levy appears in The Seattle Times. "Don't get excited and rush away only half prepared," the ad reads. "You are going to a country where grub is more valuable than gold and frequently can't be bought for any price. We can fit you out quicker and better than any firm in town" ("Klondyke"). The gold rush will remain heated for the next three years, and Cooper & Levy will reap enormous profits as Seattle's leading Yukon outfitter.

A Buying Frenzy

Isaac Cooper (1857?-1945), a New York native, had been a businessman in Farmington, Whitman County, before coming to Seattle. His brother-in-law Louis Levy (d. 1947) was a California native who ran a general store with his father in Genesee, Idaho. Levy moved to Seattle in 1889, Isaac Cooper and his wife Lizzie Levy Cooper followed in 1892, and both families were prominent in the city's Jewish community.

Their partnership began in 1892 with a small grocery store on what was is now Post Alley. Rapid growth soon led them to a larger space in the city's commercial center at the southeast corner of 1st Avenue and Yesler Way in Pioneer Square. This larger operation was a retail and mail-order grocery, hardware, and woodenware store. It advertised aggressively, and by August 1896, when news broke of a gold strike on Rabbit Creek, a Klondike River tributary, Cooper & Levy was one of the busiest stores in Seattle. Prospectors immediately began heading north to the Yukon through Alaska, but it wasn't until July 17, 1987, when the Portland arrived at Seattle laden with two tons of gold, that the Klondike Gold Rush ignited into a frenzy.

"Hard times in the State of Washington vanished in a day," wrote Edmond Meany in his 1909 book History of the State of Washington. "The good news was electrical. Orders were telegraphed for miners' supplies of every kind. People talked of nothing else, but in addition to hopeful talking they began active work, preparing to secure in some way a part of the newfound riches. Thousands made ready to brave the dangers and hardships in person. These included lawyers, preachers, business men, laborers, men of all kinds, and not a few women; even the newly elected mayor of Seattle [William D. Wood] left his position to join the stampede" (Meany, 294).

Mining the Miners

On July 16, 1897, The Seattle Times reported that the upper waters of the Yukon, "have opened up and yielded to the pick of the miner the most wonderful output of gold ever known before in the world. The little steamer Excelsior, which arrived in San Francisco yesterday, carried down three quarters of a million of gold, largely obtained during the last twelve months by the very people who had dug it out of the earth" (Meany, 293). The following day, July 17, the Portland arrived in Seattle. A day later, Cooper & Levy posted an eye-catching advertisement in the Times. Under an illustration of two miners paddling upstream, presumably on the Klondike River, it read:

"KLONDYKE. Don't get excited and rush away only half prepared. You are going to a country where grub is more valuable than gold and frequently can't be bought for any price. We can fit you out quicker and better than any firm in town. We have lots of experience, know how to pack and what to furnish. Cooper & Levy, 104-106 First Avenue South, One Door South of Yesler Way" ("Klondyke").

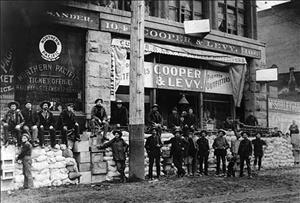

Cooper & Levy was one of dozens of Seattle stores vying to outfit the legion of prospectors intent on reaching the gold fields. According to the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, "Seattle offered numerous companies that could outfit miners -- sometimes in a single stop. Some of the city's retailers captured Klondike trade by marketing complete outfits that included food, equipment, and clothing. The Columbia Grocery Company, Seattle Trading Company, and Fischer Brothers, for example, offered this service ... Cooper & Levy was among the largest and most heavily advertised of the city's outfitters ... During the gold rush, large stacks of goods outside this store became a common sight -- and it remains an enduring image of Seattle street scenes from the period" ("Reaping The Profits ...").

Cooper later shared his memories of the "stampeders" in a 1922 article in the Times. "To many of them, this Klondike was but a golden dream, an oasis where gold was to be had for shoveling it into a large bucket," Cooper recalled. "There came here the helplessly inefficient, the men who never had held a spade or pick, who lacked physical stamina and moral courage. Some, grubstaked by friends in the East, spent their money in riotous living in Seattle and never got North. Others got only a short distance from the steamer at Dyea or Skagway, looked at the country over which they would have to make a rugged trail, grew faint-hearted and hurried back" ("Miners' Needs Met"). Cooper noted that the city was bedlam after the Portland docked, with prospectors arriving from every corner of the globe. "In ninety days there came into our store the peoples of nearly all the nations," Cooper said. "Men from Chile rubbed elbows with those from Peru, South Africa and Australia, as one and all eagerly sought to place orders for outfits for the Klondike" ("Miners' Needs Met").

Packing for the Yukon

Getting to the remote Yukon would be an epic adventure. More than 100,000 people tried but only 30,000 reached the new town of Dawson City, the entryway to the gold fields at the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon rivers. People and animals died in myriad ways, including 65 men who perished in an avalanche at Chilkoot Pass. Thousands of dead pack horses littered the treacherous White Pass Trail (later dubbed The Dead Horse Trail). Dysentery, scurvy, malaria, typhoid, and starvation were common.

Crucially, in order to cross the mountain passes into Canada en route to the gold fields, the Canadian government required each party to have enough food to last one year. This meant packing a ton or more of goods across hundreds of miles of unforgiving land where winter temperatures could plunge to minus-60 degrees Fahrenheit. Once they reached Dawson City, the miners "still had to build their own boats and barges in time to float their belongings across the river at the start of the spring thaw. By that time, most of the large, worthwhile claims had been staked, leaving little but dashed dreams" ("Klondike Gold Rush").

Seattle was the embarkation point for roughly two-thirds of the 100,000 prospectors. "They paid dearly for transportation, subsistence, and supplies. It cost an estimated $1,000 to get the Yukon with the proper equipment. During the first month of the rush, merchants in Seattle sold more than $325,000 worth of goods to miners headed north" ("Gold in the Pacific Northwest"). One such miner, William B. Haskell, kept a meticulous record of his outfit. His food provisions included 800 pounds of flour, 300 pounds of bacon, 200 pounds of cakes, 100 pounds of yeast, 80 pounds of rolled oats, 60 pounds of dried beef, 50 pounds of dried salt, 50 pounds of rice, 50 pounds of coffee, 40 pounds of tea, and smaller amounts of evaporated fruits and vegetables, butter, and more. The total weight: 2,327 pounds.

Haskell's burden also included clothing -- mostly heavy winter wear, hip boots, rubber shoes, blankets, and sleeping bags -- and a wide array of equipment, from saws, axes, and knives to nails (30 pounds), frying pans, and medicine cases. He carried a Yukon stove, two gold scales, fishing gear, and 240 pounds of candles.

Less than a week after the Portland docked in Seattle, reports began to circulate of shortages at Seattle merchants. "We have been a little short in a few items, but are certain to be in shape for all the trade offered hereafter," Cooper told the Times on the morning of July 23. "We are running along the same as usual and will fill all orders as we have done from the first of the rush. Fortunately we had a big line of stuff on the road. Bacon will be quite plentiful, for we have already contracted for 50,000 pounds, which is on the way here. Just tell the people to come along if they want goods for Alaska" ("Provisions Plenty"). Cooper & Levy clerks toiled day and night in the store, and soon "the 40 by 110-foot basement room used for packing goods became too small. Outfits made up were stacked on the sidewalk from near Yesler Way to Washington Street and around the corner to where Sylvester Brothers' store was operating a rival in the outfitting line" ("Miners' Needs Met").

Cooper and Levy Move On

The gold-rush fever remained high through 1899 before dissipating. Cooper and Levy continued to run their store until January 1903, when they suddenly sold out to the Bon Marche. A Bon Marche newspaper advertisement announcing the sale noted that Cooper and Levy's reason for selling "was simply a desire to be rid of the cares of the large retail business ... we were glad to buy with their stock the good will of a firm which has been so pronouncedly successful" ("Grocery Stock ...").

Cooper and Levy soon had pressing legal matters to tend to. Less than two weeks after the sale announcement, both men were indicted and then arrested on charges of "owning premises conducted for immoral purposes" ("Both Are Quashed"). A grand jury alleged that Cooper and Levy owned a building south of Jackson Street that was home to the infamous Midway, "a house where disreputable women ply their vocations" ("Both Are Quashed"). Four months later the charges were dropped for lack of evidence. City records indicated that the building was registered not to Cooper and Levy, but to Eugene Levy, Louis Levy's brother. Eugene Levy entered a guilty plea and paid a $100 fine. Proprietor Samuel "Midway Sam" Pinschawer admitted to running a house of prostitution and was fined $150.

Isaac Cooper wasn't done making piles of money. He and Louis Levy bought and sold real estate in Seattle, and Cooper had mining interests in Kittitas County. After Levy moved to San Francisco in 1904, Cooper went into business with Levy's brothers Aubrey, a lawyer, and Eugene, a motion-picture theater promoter, and in 1927 they built the Republic Building at 3rd Avenue and Pike Street. When Cooper died in 1945 at age 88, proceeds from his estate -- estimated at close to $1 million -- were used to fund Seattle charities, including the Kline Galland Home for the Aged and Children's Orthopedic Hospital.