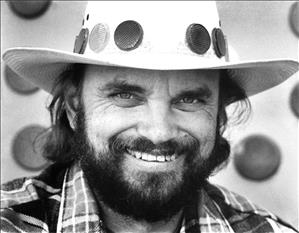

Known for grand-scale public artworks at outdoor sites around the country, Ellensburg artist Richard C. Elliott (1945-2008) turned the common bicycle reflector into a sophisticated art medium. He designed and engineered immersive museum exhibitions that felt like walk-in kaleidoscopes. In Seattle, his two-block-long drive-by experience, Sound of Light, brightens Sound Transit's Light Rail Corridor on Martin Luther King Jr. Way. Born in Portland, Oregon, Elliott grew up hindered by dyslexia, but excelling at sports and drawing. His obsessive desire to succeed gained him entry to Central Washington State College (now Central Washington University), where he studied art. It was there in Ellensburg that he met and married his soul mate, the artist Jane Orleman. The two merged their inspiration to create a fairytale house and garden — sprouting with sculptures, mosaics, whirligigs and flowers — that would become the landmark Dick and Jane's Spot. Elliott died of pancreatic cancer in 2008 and his remarkable career was celebrated in a posthumous retrospective at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem, Oregon.

A Talented Athlete

Dick Elliott always knew he was an artist. But it wasn't until he discovered the infinite creative possibilities of the Sate-Lite reflector that he found his signature style. Born in Portland, Elliott grew up in a family of high achievers. His father Jenkin Elliott was a World War II veteran who ran a successful office-equipment business. His mother Marian ran the household and took care of four children: Mary Georgina (b. 1942), Dick (b. 1945), James (b. 1948) and Thomas (now Hari Nam Singh, b. 1951). When the kids were old enough, Marian took a job as secretary at the United Methodist Church. Jenks loved sports and volunteered as a baseball coach, even before his own kids were old enough to play. Eventually all three boys learned the game under their dad's guidance — and that meant playing to win.

Although Dick struggled in school with reading and spelling, he found he could prove himself through sports. His September birthday made him the youngest and one of the smallest in his class, so he compensated by pushing himself to be best at whatever he could. When he was in third grade, his father installed a tetherball in the back yard of their suburban home in Lake Oswego. Dick spent hour after hour alone, pounding on that ball. By fourth grade he was the school champion. On his summer vacation at church camp, Dick took on all challengers — even high school kids and adults — and the little fourth-grader beat them all. In high school, Dick lettered in football, basketball, baseball, and tennis, and was captain of the basketball team.

By then Elliott had become something of a loner. He didn't hang out with classmates after school or have steady girlfriends. Like many creative individuals, Dick found himself deeply conflicted. Sports and competition were one way for him to please his father and build self-esteem. But how could he express his inner self? He signed up for an art class and spent hours at home engrossed in drawing.

College in Ellensburg

Elliott graduated from Lake Oswego High School in 1963 and, with his reading difficulties, seemed an unlikely candidate for college. He'd been told he only had a 10 percent chance of making it through the first year — a prediction he took as a challenge. When he was accepted at Central Washington State College, Elliott made it a rule to study two hours for every hour in class. He would comb through his textbooks, over and over, until he could make sense of them. Even so, his spelling did not improve. In a two-page essay he might misspell more than a hundred words, sometimes spelling the same word three different ways. Nevertheless, his intellect and creative ideas stood out. He loved to recall the time he took a bluebook exam that came back with 50 misspelled words circled in red. But for the essay's content, the professor gave him an A-plus.

Once he had proven to himself and his parents that he could do well in college, Elliott began to let his grades slip. A former classmate later remembered Dick as a good student who didn't get good grades. Instead, he stood out for an almost uncanny ability to focus, a kind of Zen-like mindfulness.

This was the mid-1960s and on campus Elliott was exposed to radical new ideas through guest speakers, including research psychologist and LSD advocate Timothy Leary; philosopher Alan Watts; architectural theorist Paolo Soleri (1919-2013), and spiritual leader Ram Dass, author of Be Here Now. Arts faculty members William Dunning (1933-2003) and Sarah Spurgeon (1903-1985) helped guide Elliott's creativity and coursework, along with another influential teacher, the jewelry artist Ramona Solberg (1921-2005). Elliott's later penchant for using found materials has an early referent in Solberg's work.

Revelations in Alaska

The Vietnam War loomed over college life and Elliott was a leader of the antiwar movement on campus. For him, the life-and-death issues facing his generation of young men made schoolwork feel irrelevant. He decided to leave the university and become a VISTA volunteer. Volunteers in Service to America, founded in 1965, was a government program promoted as a way to help fight poverty through education, economic opportunity, health care, and disaster relief. Elliott signed on and was sent to Alaska, to the small Inuit village of Pilot Station, 430 miles northwest of Anchorage by air. The 250 Indigenous people who lived there — many who didn't speak English — were among the poorest in the nation. Elliott's assignment was to help integrate them into the white education system and way of life. He believed in the mission and set out to do just that.

But within weeks, Elliott saw the government plan was misguided. He found the Inuit way of life was practical, spiritual, creative, and admirably suited to the challenges of living in a harsh environment. The people knew how to make everything they needed to survive, from clothing to dog sleds to fishing gear and tools. Changing the Inuit lifestyle, Elliott realized, would be more beneficial to the U.S. government than to the Native people. So, with his usual fervor, Elliott set out to learn from the Inuit. His new skills included ice fishing, rabbit snaring, eating moose heart, net fishing on 48-hour shifts, driving a sled in minus 20-degree weather, and Eskimo dancing.

Dick Meets Jane

After a year in Pilot Station, Elliott transferred to the Makah reservation in Northwest Washington, and then returned to Ellensburg in the spring of 1968 — where he burned his draft card in front of the student union building. He returned to Portland and requested status as a conscientious objector, which was denied. Yet, for some reason, he was never drafted. Uncertain about his future, Elliott decided to finish college. When he got back to Ellensburg, a friend introduced him to art student Jane Orleman. Soon, they were living together. "There was some deep connection that didn't really have a question to it," Jane recalled. "Complete acceptance, comfort, excitement. No question."

In 1971 Dick and Jane both graduated. They got married and moved to Portland, where Dick worked for his dad in the family Business Machine Company. Although Dick turned out to be a terrific salesman, passionate and engaged, he had no time left for art and Jane was unhappy in the suburbs. This wasn't the creative life they had envisioned. Dick quit, and eventually he and Jane landed back in Ellensburg. To support themselves, they opened a cleaning business, Spot Janitorial, named after their dog — an enterprise that made just enough money to keep them, "independently poor," as Dick's family liked to say. Still, working for local businesses gave them a foothold in the community and eventually led to their involvement in city planning and policies. Dick began devoting himself to drawing: interior scenes, portraits, and large-scale landscapes. He marketed the drawings himself, distributing postcards with reproductions and his contact information. He didn't find many takers.

As he and Jane looked for a permanent place to live, they set their sights on a former drug house, so filthy and run-down the city considered tearing it down. The two artists, however, saw potential and took on the project. After intensive cleaning and shoring up, they made the place livable; then, inspired by a whirligig display created by a self-taught artist near Grand Coulee Dam, they began adding artworks to the yard. First an eccentric found-object fence, then every kind of funky sculptural object that appealed to them or that they and their friends felt like making. They painted the front walk. There was color and pattern everywhere. Soon, reporters and television cameras began showing up and people came to gawk at the smile-inducing house and garden the owners dubbed Dick and Jane's Spot.

But even as the couple's reputation as so-called outsider artists spread, Elliott was working on a series of large drawings, up to seven feet wide, that showed his skills as a draftsman and his patience for intricate detail. With almost photographic realism, Elliott reproduced scenes from his daily life. Whether a vast swath of awe-inspiring landscape or a mundane view of a local supermarket interior, he applied laser-focus to every element of the composition. One day, out drawing in the Kittitas Valley, he was suddenly filled with what he called an "experience of the living earth." He later wrote, "Everything I perceived was alive and filled with consciousness ... our mundane human concerns melted into triviality." That epiphany would lead Elliott to "new ways of thinking about imagery, light, time, space, and human drama ..."

Finding his Artistic Footing

The first step was backward in time, as Elliott dredged up the intensity he'd felt living with Alaska Natives, their imagery and rituals. As he sought a more fundamental way to express his creativity, he began to explore tribal art forms. For his first Seattle group show at Traver/Sutton Gallery, in 1982, Elliott created a "Magic Circle" of totems and painted rocks. That idea led him and Jane to follow up with a punningly titled "Rock Festival" at a friend's property near Bothell, to celebrate the upcoming lunar eclipse. Friends and fellow artists created rock-themed art of all manner and Dick planned a performance around an installation he called "Portable Lunar Observation Piece." With a nod to Stonehenge, he laid it out around a circular plastic wading pool with salvaged banister posts painted in bright patterns and embellished with colored bicycle reflectors to catch moonlight. Then, dressed in a painted and feathered hardhat and anointed Chief Lunatic, Elliott performed some sort of ritual. Music blared and intoxicants flowed. Memories of the event apparently faded with the moonlight. But that night marked a transition in Elliott's thinking.

As he explored primal creative expressions and outsider art, Elliott found they connected to what was happening in contemporary art circles as well. Installations, performances, earth art, graffiti: Art that grew out of instinctive urges was leading artists away from traditional gallery settings. In 1983 Elliott began a period of "intuitive groping," as he worked on a series of small drawings, dated day after day, from January 23 to May 10. He called them "Meditations," and those 127 systematic variations of dots and lines within a square field vibrate as you look at them, with the psychedelic effect of 1960s Op art.

That led Elliott further still, to a series of paintings that were related to his totems and fetishes, but showed the craft and polish of his academic training. He painted rhythmic abstract designs in gemlike colors on surfaces studded with reflectors, mirrors, feathers, nails, and glitter. The images were entrancing. He showed them in 1988, with some of his fetish-style constructions, at Seattle's Mia Gallery in Pioneer Square. Owner Mia McEldowney marketed the work of self-taught Southern artists as well as Northwest artists whose work fit a folk art aesthetic. Elliott's Light in Spirit exhibition drew plenty of attention. But, unfortunately, that venue also added to the notion that Elliott was a self-taught "outsider." When Mia Gallery closed, his work was not picked up by another Seattle gallery.

Undaunted, Elliott had already moved forward and was homing in on his true voice, his signature style. He found a way to distill the multi-media paintings to their essence: light and pattern. Using a labor-intensive technique of layering Sate-Lite reflectors, Elliott created mosaic-like surfaces that would ignite as sunlight passed over them. Henry Art Gallery curator Chris Bruce saw some and was wowed. He invited Elliott to create an installation at the Henry and they agreed on a series of assemblages that would fit into the nine arched alcoves around the building's exterior, like stained glass windows. Originally planned to remain in place just for a year, Cycle of the Sun was so popular the museum purchased it for the permanent collection and reinstalls the piece periodically. Bruce has described Elliott as "one of the great innovators in the history of Northwest art and one of the most accomplished yet under-recognized artists in America."

Growing Acclaim

The Henry Gallery's prominent endorsement brought Elliott a rush of new commissions from museums and college galleries around the Northwest. As one reviewer put it, "Through an intuitive alternation of light-absorbing and light-reflecting colors, Elliott propels the viewer into the very matrix of vibrating energy that pervades, surrounds and interlocks all matter." Driven to accomplish more, Elliott trained in a new skill: neon tube bending. With that difficult technique part of his repertoire, he now could make artworks that produced light, as well as ones that reflected it.

In 1992, Elliott won his first major public art commission, and it was huge. He would create a sparkling hatband of reflector patterns to circle the exterior of Yakima's new sports arena, the Yakima Valley SunDome. The logistics were formidable. After three months of design and planning, Elliott spent six weeks strapped to a safety rope on a network of scaffolding, as an assistant read off color combinations from a plan. In the glare and heat of high-desert summer, Elliott, glue-gun in hand, affixed nearly 50,000 reflectors around the circumference of the dome's concrete rim, in a 5½ by 880-foot circle. Mind-numbing, sweat-drenching, vertiginous work: for Elliott, a dream job. An instant hit, Circle of Light attracted other public art opportunities, the most exciting in Manhattan's Times Square in 1993. Elliott was commissioned to create a 17-by-40-foot mural on a building slated for demolition. The jazzy, zig-zagging patterns of the piece, amplified by surrounding lights, was so eye-catching that a photo of it landed on the cover of the art section of The New York Times.

A Tragic Turn

But just two years later, at the height of his popularity, Elliott suffered a dangerous setback. An accident in his neon shop exposed Elliott to toxic mercury vapors. Hospitalized in critical care for a week, he sustained damage to his heart and a string of other ailments that became chronic, dampening his once formidable energy, putting him in and out of the ER, and dependent on Jane and his assistants. His seemingly endless capacity for hard physical work vanished.

John Olbrantz, then deputy director of Bellingham's Whatcom Museum of History and Art, had been following Elliott's work for years. In 1996, Olbrantz worked with Elliott to plan a major retrospective called Explorations in Light. The entire museum staff, interns, and work study students joined Elliott to follow his intricate design drawings and nail some 10,000 reflectors on the walls, creating two huge new assemblages, one 6½ by 17 feet and the other 16 by 16 feet. Those, along with a selection of Elliott's neon pieces, reflector on canvas assemblages, and fetishes made the show feel like a cross between a cathedral and a psychedelic lightshow. When the show opened, visitors were blown away. Olbrantz became one of Elliott's most devoted supporters.

In 1998, Elliott had a pacemaker inserted to prod his heart along. And he continued to work in his studio, painting and drawing, as well as designing dynamic new public artworks and museum installations. His friend and assistant, Dick Johnson, became the primary fabricator of Elliott's assemblages and helped with anything that needed a hand. Jane, in addition to her own painting and writing, had long been Elliott's able helpmate: editing and correcting his proposals, doing the bookkeeping, managing the archives, running the website, writing press releases, being the pragmatic boots on the ground that allowed Dick's creative work to flow. They were, as one friend said, "a binary entity," their lives and artwork interwoven.

On September 17, 2007, two weeks after his 62nd birthday, Dick was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. With his strength declining, Elliot could no longer paint, so he transferred his production onto a computer. "If I feel good enough to sit in a chair," he wrote, "I can work." An amazing group of images, called the Vibrational Field series, absorbed Elliott during his final year. He raced to set down all the possibilities that swarmed in his mind and, with a palette of thousands of color gradations to choose from, his work took on a joyous, almost out-of-body lightness. He described it as "like tuning forks setting up a resonating vibration that brings our soul into its harmonic." When he completed #57 of the series, he told Jane, "If this is the one I have to end on, I'm okay with that."

The final decade of Elliott's life had been amazingly productive. With assistance from Dick Johnson and others, he had completed some 20 large-scale public art projects, including "Tower of Light," on an outdoor elevator at the Archdale Station at Charlotte, North Carolina; and "Thunder over the Rockies," a contemporary cave painting at the Belleview Light Rail Station in Denver, Colorado, both in 2007.

In addition, he continued his fascination with delineating every permutation within a set of possibilities. An ambitious group of prints composed on a computer, the Eidetic Variations comprised 13,275 gradated designs, assembled in grid-form on 185 laser prints, each with 72 individual patterns presented sequentially. Each individual design was built from a central point in radiating arrangements of red, green, gold, blue, and white dots. The term "eidetic" refers to an exceptionally detailed recollection of visual imagery, which perfectly fit Elliott's concept. He installed the work in a 2006 exhibition at the Larson Gallery at Yakima Valley College, where the prints wallpapered the space in overwhelming complexity.

After that computer-assisted tour de force, Elliott returned to the low-tech medium of paint on canvas and the inspiration that had long fueled his work — primal patterning and optical illusion. And now he put a name on it: "Primal Op." He also designed his final public art landmark, Sound of Light. The thirty-seven-panel, two-block-long drive-by experience stretches along Sound Transit's Light Rail Corridor on Martin Luther King Jr. Way and was completed in 2008. Elliott received an Americans for the Arts award for the piece, but was bedridden and could not attend the ceremony in Philadelphia. In January 2008, he also received the Governor's Award, Washington state's highest honor in the arts.

On November 19, 2008, Elliott died at home with Jane at his side. In May 2014 the Hallie Ford Museum of Art, in Salem, Oregon, led by director John Olbrantz, opened a retrospective exhibition to honor Elliott's remarkable career.