In this original essay, historian Vicki Halper writes about Dick and Jane Lang, who married in 1966 and over the ensuing 16 years -- until Dick's death in 1982 -- filled their home on Lake Washington with a stunning collection of contemporary art. After Jane died in 2017, her family's Friday Foundation donated 19 major works to Seattle Art Museum. They were featured in the exhibition Frission: The Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis Collection, which began in October 2021 and was scheduled to run through November 27, 2022.

An Unanticipated Leap into Art

When Richard Lang met his future wife Jane in 1965, he was living in a substantial house east of Seattle, decorated in British country style with crewel upholstery, a medley of furniture, and a suite of English hunting prints over the fireplace. At the time of Dick's death in 1982, the home they had built together on Lake Washington was comparatively restrained, with Mediterranean details and white walls. On these walls was a collection of predominantly abstract expressionist paintings, limited in number but so staggering in quality that it propelled the couple into the upper echelons of American collectors. A substantial selection of these paintings and two important sculptures were donated to the Seattle Art Museum (SAM) in 2020, providing the institution with a deeply enriched base for its outstanding contemporary art collection. The city, once belittled as a provincial outpost of the arts, has become a destination for art lovers and connoisseurs.

The leap from hunting prints to abstract painting was unanticipated. The Langs had planned to keep their walls pristine until Jane decided they could use a painting over the couch. When she brought Dick to the Marlborough Gallery in 1970 on one of their regular trips to New York, he focused on a bold black-and-white canvas by Franz Kline, which became the cover image for the catalog of their collection that was published by SAM in 1984. The art that would join the Kline was never color-coordinated to the decor, but constricted by the available space. Their collection was complete before Dick died. Almost nothing had been sold, nothing stored, and little subsequently purchased by Jane. Other than loans for national and international exhibitions and a few donations to SAM, they lived intimately and consistently with their art.

Given the remarkably swift changes in the art scene after the ascendance of the New York School of abstract expressionism — including pop, minimal, conceptual, installation, and figurative styles — most of the artists whose work the Langs bought were contemporary Old Masters. The Langs did not frequent artists' studios or seek out recent work. Rather they bought from other top-tier collectors and established galleries, sought advice from knowledgeable friends, and became attentive to early works that remained in artists' estates. They were neither scholars nor dilettantes, but focused and passionate buyers whose purchases preceded the explosion of the art market by a lucky few years, and whose remarkable taste was restrained by the remaining spaces on their walls.

Richard E. Lang

Dick Lang was a lifelong Northwesterner. Born into a German-Jewish family in 1906, he was raised in a Catholic neighborhood in Seattle, near the Holy Names Academy and the Central District. His father, Julius C. Lang, had established himself as a distributor of wholesale groceries by following the Gold Rush up the West Coast. While Dick shunned the word "wealthy" for the more modest term "well-to-do," and attended some public schools until college, his childhood home had servants, a cook, and a chauffeur (Richard Lang interview with Howard Droker, 1981).

Father and son were deeply tied to the Jewish community, although neither considered themselves ethnic Jews. (Dick's mother was a member of an elite German Jewish group in Seattle called the Cuckoo Club, but had not been raised in the faith.) Julius identified himself as 100 percent American with German ancestors. He and Dick served for extended periods as board members and presidents of Temple de Hirsch Sinai, a Reform congregation, among their many other civic activities. By culture and class, this congregation of Germanic heritage was as divorced from later Jewish immigrants (mainly Eastern Europeans Jews fleeing the Holocaust), as they were from the neighboring Black communities.

As was often the case among Jews in the American west before World War II, Julius, Dick, and their congregation were anti-Zionist, Julius vehemently so. Dick ended his association with Judaism and the synagogue in 1944, likely in part because of his meeting with a group of Orthodox rabbis who prioritized establishing the State of Israel over granting asylum for endangered Jews during the Holocaust. Dick later reported to his family that these rabbis had argued against his attending a meeting with President Franklin Roosevelt about loosening immigration restrictions because they believed that the establishment of Israel was more likely given the annihilation of Jewish communities in Europe (Lyn Grinstein interview with author). There is no written record of this meeting, and Dick would not speak about leaving Temple de Hirsch Sinai in his 1981 interview. When he broke formal ties with the synagogue, a star was placed next to his name on the roster, indicating that, like other starred individuals, he had died.

After college and law school at Stanford University (J.D. 1929), Dick returned to Seattle, became head of the family's food wholesale and distribution businesses, the leading broker of the Northwest fur trade, and president and chairman of the National Grocery Co. (later Lang & Co.). For years he held what was called the Jewish seat on many boards of directors, including Safeco and Seafirst corporations.

In 1962, along with his mother and first wife, Dick commissioned a sculpture for Seattle's Century 21 World's Fair. He had attended the 1958 World's Fair in Brussels, where he saw an abstract stone column designed by the French artist François Stahly. Lang asked the sculptor, who had become a visiting professor at the University of Washington, to use the column in a new fountain in honor of his father, Julius Lang. The fountain is likely Dick's first donation of art as well as his first support of abstract imagery. The column had already been vetted by its display at the Belgian World's Fair, a seal of approval before purchase that the Langs often sought later.

Dick eventually became a trustee of Seattle Art Museum, and was a major donor to Stanford, endowing the chair of the dean of the law school, and later presenting a significant Alexander Calder sculpture to the university. That gift was made after he met Jane.

Jane MacGregor Hussong Southwell Lang Davis

Dick is remembered as an alpha-male: focused, competitive, decisive, skeptical, sometimes abrasive, and handsome. Jane is remembered as exuberant, energetic, funny, uncensored, and stylish. Great legs. Great, but wicked, humor. Unfailingly upbeat. The woman who, in her mid-70s, wore shorts to board meetings after games of tennis, and lounged with a vodka after her helicopter crashed during a fishing trip in Mongolia. Yet her daughter, Lyn Hussong Grinstein, said that after creating a great art collection, her mother's major achievement might be surviving her childhood with grace and verve.

Jane MacGregor was born in 1920 in Philadelphia. The Roaring Twenties started well for her family. Her father, Donald Ross MacGregor, had trained as an artist and worked on the turn-of-the-century murals that remain in the grand Pennsylvania State Capitol building in Harrisburg. However, as the eldest of four sons, he was required to take over his father's construction company. He settled down, married Mae Widmer, first had a daughter, Jane, and within 10 months of her birth the desired male heir, Donald.

Jane's mother was fiercely independent and modern, undoubtedly one source of her daughter's spunk. For example, after years of crusading, Mae became the first woman in Pennsylvania to receive a driver's license. On January 2, 1925, she took a quick lesson from her chauffeur, and loaded her two children into the automobile for her first official drive. The roads were icy, she skidded, and crashed. Young Donald was killed. In the aftermath, Jane's father's health steeply declined, and Mae was hospitalized for trauma. Jane was sent to live with a beloved maternal aunt and her financier husband, Elsie and Howard Reynolds.

The stock market crash in 1929 initiated the Great Depression. Nine-year-old Jane was walking home from school when she passed a newsboy who was hawking papers and shouting out a headline: her Uncle Howard, suddenly impoverished along with many others, had just committed suicide. Her father soon died from a stroke.

The two Widmer sisters moved in together to raise Jane. Mae converted her home into a boarding house. All that was left of the MacGregor wealth, which had been slowly pilfered by the remaining brothers, were a few pieces of silver, some jewelry, and three unsinkable women. Jane's childhood influenced her taste for a lifetime. "My mother thought of sentimentality as a waste of time," Jane's daughter said. "She was not interested in pretty, easy, or sweet" (Lyn Grinstein interview with author).

In 1940, while studying design at the University of Pennsylvania, Jane met and married the first of her four husbands, Jacques Hussong, an Army officer. During World War II she stenciled numbers on airplanes and tankers, the patriotic end of an aborted art career. After the war and Jacques's receiving a degree in engineering, Jane sought adventure for her young family. Learning of opportunities in foreign oil fields, and wishing that their children Lyn and Don would see the world, in 1954 she encouraged her husband to take a job with the Caltex Petroleum Corporation in the Philippines. Three years later the family transferred to Bahrain Island in the Persian Gulf, a barren desert sheikdom. Jane was one of the rare Western woman living there whose sociability, curiosity, and self-confidence led her to engage with the sheiks' wives and prominent Indian and Arab merchants.

Lyn Grinstein explained her mother's departure from the Middle East with her second husband, Jim Southwell, by contrasting Jane's vivacity with Hussong's demeanor as a "gentle, studious, and conservative engineer." With the children abroad in high school and college, Jane moved with Southwell to Frankfurt, Germany, then La Coruña, Spain, in effect continuing her world tour. When Southwell died prematurely in 1964, Jane went to Hawaii, where her son lived, and expected to stay there. Then she was introduced to Richard Lang, who was on a golfing trip from Seattle.

Jane, who had lived a peripatetic life into her forties, married Dick in 1966, and finally found a permanent home as a dedicated Northwesterner. The community he introduced her into was influential at the apex of regional businesses and cultural institutions. She thrived in the social scene, and renewed her interest in contemporary art. Jane oversaw the remodeling and extension of a lakeview home with touches of Spain. The house had the white-walled potential to frame the Langs's then unforeseen collection.

Virginia "Jinny" Wright, a driving force in the region's developing art scene, became Jane's intimate friend. Wright was committed to having her unexcelled modern art collection housed within the broad context of world arts rather than isolated in a contemporary or private art museum. Even collections that could have been competitive with hers, such as the Langs's, were not seen in rivalry. Charles Wright, Jinny and Bagley Wright's son, said that his mother thought of the Wright and Lang collections as a unit. When Jane and Dick purchased a work by Clifford Still, for example, Jinny, who desired one of his rarely available paintings, said, "Good. Now I don't have to get one." Another friend and collector, Betty Hedreen, said that Jinny stayed away from buying Philip Guston's work because "Jane had two wonderful ones." Their styles of purchase continued to differ, with Jinny usually buying within a year of when the art was produced and the Langs buying "blue chip," in Hedreen's words (author interviews with Charles Wright and Betty Hedreen).

The Lang Collection

In his 1981 oral history interview, Dick Lang credits Jane, "if anybody deserves credit," for his interest in art. He did, however, own some paintings in addition to the prints over his fireplace. These pieces, which celebrated the American West, were dispersed after their marriage, including their first donation to SAM, a Sydney Laurence oil on canvas, in preference for art that they both liked. Said Dick Lang:

"Prior to my marriage I had a cattle ranch in central Washington. I had a few rather fine [Frederick] Remingtons and [Charles Marion] Russells. In Seattle I had some Sydney Laurences, the Alaska painter. When we were married I disposed of the ranch and the Remingtons and Russells and all but one Sydney Laurence which I had in my office ... It wouldn't have hurt here but it wouldn't have contributed anything. At least my wife didn't think so ... Several years after we were married we were in New York. My wife said, 'Please take an afternoon off from work and spend it with me. I'd like to go and show you a lot of the galleries.' At the time we built our home we had agreed we would have what we called elegant simplicity and have nothing on the walls. Prior to this particular trip to New York she said, 'I think we should make an exception and we should have one painting over the couch in the living room.' That afternoon that I spent with her, we were at the Marlborough Gallery. I saw what I called a picture and was corrected and told it was a painting, which was purchased a few months later, which was the beginning of the urge to have only [the] unusual -- that means that it appealed to both of us. It was a Franz Kline that is one of his greatest works, that I happened to like. She jokingly said, 'Well you might like it but you'll never buy it'" (Lang, 1981).

Given the months between the Langs's visit to the Marlborough Gallery and the purchase of the Kline, it is probable that others supported their acquisition. The Wrights would have approved of the choice, since Jinny's husband, Bagley, acting alone, had purchased a similar muscular Kline in the early 1960s. Jane's daughter recalls that Dick sought advice in this instance from Stanford art history professor Albert Elsen, to whom he'd been introduced by a mutual friend from law school. Such consultation would have initiated their habit of vetting future purchases with experts, collectors, and gallerists.

Some friends credit Jane and others credit Dick with the outstanding quality of their collection, but it is likely that neither had consistently greater influence when it came to choosing pieces for their home. Jane had art training and was a dedicated museum goer. But Dick was a quick study and adventurous in his taste. He also held the purse strings. Laura Paulson, who was a receptionist at the David McKee Gallery late in the Langs's collecting history, recalls them sitting side-by-side as paintings were brought out for their lengthy consideration. As neither one of the couple was shy with opinions, mutual decision-making was likely the rule.

In 1973 Jane bought three excellent small abstractions from the estate of Alice Trumbull Mason, with whom she had briefly studied in New York. She probably purchased these on her own, and did not consider them part of the Lang collection, as she later declined to include them in the otherwise complete exhibition of the collection at SAM in 1984.

Dick had the role of negotiator, which he relished. Jane would "bring him in for the kill," Grinstein noted. Dick handled prices and conditions of purchases, and sought discounts, free shipping, and payments over time -- nothing unusual for a top-tier collector. He was strongly invested in seeing that the art collection would have a secure future. George Steers, his lawyer, said Dick was deeply committed to the arts community and wanted to know how to "make a gift and be assured that it would be properly displayed, cared for, and that the organization would survive" (George Steers interview with author).

While the Wrights made their collection a promised gift to SAM, the Langs did not do so during their lifetimes, leaving the museum on edge about their intentions. Bruce Guenther, who replaced Charles Cowles as SAM's contemporary art curator in 1979, recalled that his first assignment from then acting director Bagley Wright was to "make sure that the Lang collection stayed in Seattle." Guenther found pretexts to visit the couple monthly, a delightful chore, he wrote:

"Jane lived large and loved art. She was one of those great people in my life, and a hilarious gossip. Jane was always on my side. I thought of her as the fun-loving, life-embracing Dionysian, in contrast to Jinny Wright's more Apollonian conservative demeanor.

Dick was a pragmatist, a businessman, and wanted to see things happen. The museum was having problems with a new downtown site and its capital campaign. Dick wanted to make sure his collection went to a museum that was going to be there. It would be a memorial to him and Jane. He talked about art with intensity, and was drawn to the abstract expressionist mythos of a solitary guy battling it out in the studio" (Bruce Guenther interviews with author).

In 1974 the Langs bought their first portrait study by Francis Bacon and found an Alberto Giacometti sculpture of an elongated woman that they purchased the following year. The figurative pieces that they added to their collection, however, exhibited the gestural surface and element of anguish that were shared by many of the abstractions on their walls. Guenther, the new curator at SAM, had a similar aesthetic; for example, he was drawn to the recent paintings of German neo-expressionists such as Georg Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer. He recalls encouraging Dick and Jane to buy Lee Krasner's Nightwatch and Philip Guston's The Painter, two brilliant if deeply disturbing paintings. Dick, who had wanted Bacon to paint his portrait, spent his last days before dying at home of cancer on a bed face-to-face with the Guston.

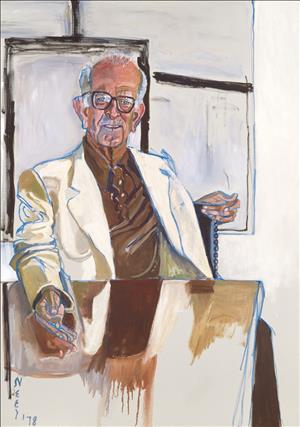

Dick died in 1982, before The Richard and Jane Lang Collection exhibition opened at SAM in February 1984. The exhibition contained 43 paintings, drawings, and sculptures -- the complete collection except for a David Smith sculpture that was installed in the Langs's garden and the three Mason abstractions (which were not illustrated in the catalog). The exhibition received rave reviews. A Warhol diptych of the vivacious Jane, which had surprised the collector who didn't know about Dick's secret commission until the opening of the Warhol portrait exhibition at SAM in 1976, had pride of place. A portrait of Dick, painted by Alice Neel after Bacon turned down Dick's request, was also exhibited, and is described by those who knew him as eerily capturing his character. The portraits were independently donated to SAM by family members between 1976 and 2020.

After the exhibition, the art was returned to the walls of the house, and stayed there throughout Jane's subsequent marriage to Dr. David Davis, which lasted until her death in 2017. It remained the background to gatherings of family, the visual arts crowd, and the ballet, opera, and symphony cognoscenti who were also a large part of Jane and David's lives.

Nineteen major works of art were donated to Seattle Art Museum in 2020 through the Friday Foundation, which was established by Jane's family after her death. The remaining pieces have been dispersed or are with the foundation, which continues to support the institutions that Jane and Dick helped sustain. Seattle, however, remains the place to see the Langs's aesthetic as a whole, and be in the painted presence of Jane's joie de vivre and Dick's emphatic spirit.

Also by Vicki Halper: Seattle Art Scene: From Century 21 to the Seattle Art Museum