Pinball machines were introduced nearly a century ago and immediately became wildly popular. Unlike today's versions, though, early pinball games were played for gambling purposes, which proved to be controversial -- especially in Seattle, where they ignited a tumultuous feud between local crime syndicates and played a key role in some of the city's most salacious political scandals. The arrival of pinballs coincided with the repeal of Prohibition, and pinball machines soon became common in taverns, pool halls, and seedy nightclubs. At Seattle City Hall, pinballs became contentious; they brought in enormous amounts of tax revenue but were tainted by known criminal activity.

Early History

The first pinball machines were introduced during the early 1930s and were based on a French tabletop game known as bagatelle. These early pinballs didn't have flippers. Rather, they were played as games of chance in which the ball was launched onto an inclined playfield, and except for some gentle nudging of the machine itself, the player had no control over the ball's final outcome. Money and prizes were issued if the ball happened to land in certain slots, resulting in pinballs becoming a wildly popular form of entertainment. This triggered a national debate regarding the legality of such machines and if they represented gambling or not. Stories emerged of school children spending their lunch money on pinballs. The fact that many of the early machines were manufactured in Chicago (which at the time was considered the nexus of organized crime) didn't help ease any of the controversy. As a result, pinballs soon became outlawed in many cities and states throughout the country.

Pinball machines initially remained legal in Washington, though some local municipalities began questioning how pinball machines should be regulated. In Seattle – where pinballs proved to be especially popular – the city council recognized the potential revenue that could be realized with such devices and imposed a hefty licensing fee for each pinball machine within the city limits. Despite the money that pinballs generated for the city, officials often found themselves in a quandary over their legal status. The matter was settled somewhat in 1937 when Washington Governor Clarence D. Martin (1886-1955) signed legislation that banned pinball machines, except where the element of skill predominated, and mandated that legal pinball operators were to pay a state business tax on each of their machines. But because it was never explicitly explained how the issue of skill versus luck was to be determined, the legal status of pinball machines remained murky for the next few decades, with different towns and counties establishing their own interpretations into law. In most places, pinballs were generally tolerated due to the tax revenue they generated.

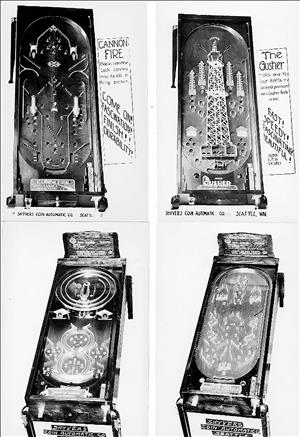

One of the earliest pinball enterprises in Seattle was the Shyvers Coin-Automatic Company. Opened in 1934 by Kenneth Shyvers (1899-1976), it served as the city's top distributor for coin-operated machines. Shyvers was known for designing some of the earliest known pinball machines and strongly campaigned against their criminalization, once telling the media, "There was never any intention that these machines should be used for any purposes other than games of skills" ("Orders Issued on Lotteries")

By the early 1940s, the popularity of pinball machines had resulted in taxation at the city, county, and state levels. More than half of all revenue collected through the state's pinball tax came from King County. This prompted local pinball operators to begin using different techniques to help falsify the amount of their reportable earnings. One such method involved boring a hole in the machine and inserting a device that would prevent the machine from recording payment. Other times, pinball operators would skim the profits by using a special key that allowed the game to operate without the use of a coin. Among pinball operators, these tricks of the trade became known as "milking," which set the stage for one of the region's first pinball rackets.

Beginning in 1942, William R. Forman (1913-1981) and his business partner Armador "Army" Seijas (1907-1966) co-owned Bremerton Amusement Company, which operated pinball routes in Kitsap County. The two men chose to establish their pinball business in the Bremerton area in order to take advantage of all the sailors and shipyard workers active there during World War II. The business was wildly successful, and Forman was able to parlay his pinball earnings into purchasing a number of Seattle movie theaters and several popular drive-in theaters. In 1953, both men were criminally indicted when it was revealed that they had significantly underreported their 1940s pinball revenue in order to avoid paying their share of taxes. Each was found guilty of tax evasion and sentenced to five years in prison. Forman would later establish the Pacific Theater movie chain and become a theater magnate.

Tolerance Policy

Seattle has a long and conflicting history of how it has tolerated such things as gambling, liquor, and prostitution. Under the "open town" policies of mayor Hiram C. Gill (1866-1919), who served from 1910 to 1911, and again from 1914-1918, vice was generally tolerated as long as it was discreetly conducted in officially sanctioned locations. Additionally, the Seattle Police Department had a known record of corruption within its ranks in which payoff money was expected from vice operators who wished to avoid arrest. In exchange, the police helped to maintain order at such establishments, an extortion system that wase seen as an effective means of controlling crime.

In the late 1940s, under the mayorship of William F. Devin (1898-1982), Seattle officially introduced what became known as the "tolerance policy," whereby police bribes were replaced by an official licensing system, and certain gambling – such as pinballs, punchboards, and low-stakes cardrooms – were allowed to operate as long as licensing fees were paid and everything remained within the parameters of the law. This flew directly in the face of state gambling laws, but the logic was that widespread police graft could be replaced with a new system of "officially condoned illegality" (Bayley) that could help fill city coffers while also encouraging vice establishments to police themselves.

The master licensing system that emerged from Seattle's tolerance policy was further designed to prevent criminal activity. Each applicant who wanted a gambling license was fingerprinted and required to have lived in King County for at least five years in order prevent out-of-town rackets from moving in. Despite their best intentions, city leaders had little idea about what unintended consequences lay ahead.

The Seattle Pinball Bombings

In the mid-1950s, a conglomerate of Seattle pinball operators formed a trade organization known as the Amusement Association of Seattle (AAS). The group's overall mission was to prevent any one person or group from taking over Seattle's thriving pinball market. This was during the height of the tolerance policy, so AAS sought to keep the local pinball industry within respectable limits. There were rules and agreements that all members were expected to follow, such as not allowing juveniles to play their machines, nor operating pinballs near schools or churches.

AAS was presided over by its secretary-treasurer, Fred Galeno (1895-1991), who maintained a close relationship with local Teamsters Union leader Frank Brewster (1897-1996). Brewster was a Seattle native who had become head of the powerful Western Conference of Teamsters, which represented nearly 400,000 members. This alliance between AAS and the city's most powerful union gave the group almost complete control over Seattle pinballs. Many of the city's top taverns formed exclusive agreements with Galeno's organization in which they carried only amusement devices from licensed AAS operators. The irony was that AAS had originally formed to prevent any one entity from taking over the city's pinballs, though it now enjoyed a near monopoly. Before long, AAS used its dominance to exploit the local pinball industry by such things as price fixing and selecting who was able to operate their pinballs and jukeboxes at which locations.

In 1956, the Tacoma City Council declared pinball machines a "public nuisance" and voted 7-2 in favor of banning them outright. That same year, Gordon Clinton (1920-2011) won the election for Seattle mayor, and despite running as a reformist candidate, he quietly endorsed the tolerance policy, which allowed pinballs to continue operating within the city limits.

AAS grew its operations amid increasing reports that workers from the Teamsters were intimidating tavern owners into carrying their machines. Their primary competition in Seattle was Colacurcio Brothers Amusement Incorporated, which ran a large pinball and jukebox operation and was owned by a trio of siblings – Sam (1925-2015), William (1921-2012), and Frank Colacurcio (1917-2010) – who were known for using strong-arm tactics to convince property owners to carry their machines. However, this was becoming increasingly difficult thanks to AAS's growing dominance. It didn't take long for tensions to start forming between the two groups.

The first skirmish took place on October 11, 1957, when a late-night bomb ripped apart the Century Distributing building, a pinball and jukebox business in the Queen Anne neighborhood. The blast was so powerful that the building's concrete foundation was pushed out by almost two feet and its entire inventory of pinballs, jukeboxes, and coin-operated devices was destroyed. The owner told investigators that he could not think of anyone having any motives for such an act, though the fact that his business had assisted AAS in taking several lucrative pinball locations away from the Colacurcio brothers did not go unnoticed by investigating officials.

The following month, Frank Colacurcio was charged with "threat of bodily harm" after three Seattle tavern owners claimed they had been threatened with physical assault if they didn't carry Colacurcio machines. There were also reports of predatory loan sharking, in which money would be loaned to tavern owners in exchange for exclusive pinball and jukebox rights. Other times, "match bombs" would be placed under rival jukeboxes. This involved putting a lit cigarette on an open book of matches, and when the cigarette burned down and reached the matchheads, it would set off a flare and start a fire underneath, usually destroying the machine's wiring. With concerns growing over the lawlessness of pinball rackets, the Seattle Police Department issued a statement declaring, "We will not allow gangsterism to gain a foothold in this community, nor will we permit intimidation of any citizen by threats or violence" ("Jukebox 'War' Curbed")

The city council was also prompted to reconsider how pinball machines should be enforced, and in May 1958, it voted unanimously against the renewal of pinball licenses for William Colacurcio, who was ordered to sell his pinball interests. Two months later, on July 24, 1958, Mayor Clinton signed a pinball and jukebox ordinance into law that tightened regulations on such machines, including a limit on how many pinball licenses would be issued for each individual operator.

On the evening of January 23, 1959, the Pioneer Card Company was the site of a second bombing. The business, located next to the Smith Tower in downtown Seattle, manufactured and sold dice, playing cards, and assorted gambling equipment. The blast blew out the windows and sent the front door hurtling out into the street. Police determined that a stick of dynamite had been dropped through the mail slot.

The following month, it was revealed that the Colacurcio brothers were getting around pinball regulations by operating dummy corporations. In response, the Seattle City Council revoked the licenses of any coin-operated businesses with known connections to the Colacurcio syndicate. This included Ken Shyvers's downtown jukebox business, which had been caught operating unlicensed machines. A couple of years prior, Shyvers had been indicted for attempting to bribe a Washington State Supreme Court Judge involved in an unrelated case. With his legal troubles mounting, Shyvers would eventually leave the coin-op business altogether and become a home contractor.

On the night of February 18, 1960, Fred Galeno's car was bombed outside his Queen Anne home. He was asleep in his bedroom, so escaped injury, though the blast was described as "deafening" and could be heard as far as two miles away. The incident triggered an immediate response from Mayor Clinton, who issued a public statement declaring that he would seek to abolish pinball machines outright if any of the bombings turned out to be pinball-related. Six Seattle detectives were assigned to the case and the FBI launched its own investigation, with the remains of Galeno's car being sent to a special forensics lab in Washington, D.C.

The timing of Galeno's car bombing also drew suspicion as it took place during a contentious mayoral election. Clinton's opponent, Gordon Newell (1913-1991), had made public statements denouncing the mayor's tough stance toward pinballs, arguing that such strict controls had only made things worse. In the early morning hours of March 5, 1960, Newell would find himself the target of the next bombing when his sports car (an Austin-Healy) was destroyed by an explosion in front of his house. Newell attributed the incident to his recent statements about the pinball industry, though others speculated that the bombing was intended to politically embarrass the incumbent mayor. Despite whatever the bomber's intentions may have been, Clinton ended up winning his bid for re-election. Newell, in turn, would exit the political stage and become the published author of such local history books as Totem Tales of Old Seattle and Westward to Alki.

On July 16, 1960, the Michael Distributing Company – the largest pinball distributor in Washington – was the site of a fifth and final bombing. Once again, dynamite had been used as an apparent means of intimidation. The damage was substantial, prompting a harsh response from Mayor Clinton, who announced that if the bombings weren't solved within a month, he would seek a permanent pinball ban. It was later revealed that the owner of the business, John J. Michael (1898-1983), was strongly affiliated with AAS. Galeno offered a $6,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of any persons responsible for the bombings.

A week later, the Seattle Police Department began using lie detectors to question pinball operators, though were unable to turn up any solid leads. Meanwhile, the mayor ratcheted up his demands that pinball machines be banned completely, arguing that they had been tolerated in the city for more than 30 years but the industry had now proven itself to be reckless and dangerous. On September 20, 1960, the city council voted 8-1 to officially reject the mayor's request to ban pinballs, though it was noted by the media that such machines were earning the city as much as $500,000 in annual licensing and tax revenue.

Scandals of the 1960s

In January 1962, the issue of pinballs gained renewed interest when the Seattle Police Department announced that, in accordance with state law, it would begin closing establishments found with illegal gambling devices. This prompted the city council to enact a policy in which "amusement only" pinball machines could still operate within the city limits as long as they didn't offer monetary payouts. Meanwhile, at the state level, the Washington State Senate voted 32-15 in favor of permitting pinballs to operate on a local-option basis, meaning that cities could decide for themselves if such devices were to be allowed within their jurisdiction.

In 1963, amid all this political activity, a federal grand jury was convened in Seattle as part of an ongoing investigation of the city's pinball industry. This led to the indictments of Fred Galeno and John J. Michael, who were charged with "overt acts" related to political payoffs given to "maintain a situation whereby gambling on pinball machines in Seattle could continue" ("Pinball Protection ..."). Galeno and Michael were found guilty, resulting in a $3,500 fine and a year of probation for each. Soon after, both retired from the pinball industry, setting the stage for the next generation of pinball rackets.

By the mid-1960s, pinballs continued to flourish as "for amusement only" devices, though it was widely understood that most existing pinballs were still being used for gambling and were bringing in as much as $6 million per year. The Colacurcio brothers still operated pinballs and jukeboxes, though they had branched out into other ventures including bars, nightclubs, and some of Seattle's earliest strip clubs. AAS had dissolved upon Galeno's retirement, with a new association of King County pinball operators known as Farwest Novelty Comapny taking its place. Farwest Novelty was headed by Ben Cichy (1898-1969) and controlled the master licenses for more than 2,000 pinball machines, pool tables, and bowling games in the region. The local media dubbed Cichy "the pinball king."

In 1968, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle magazine, and KING-TV joined forces in an investigation regarding high-level payoffs and corruption in King County. The ongoing investigation resulted in a scathing news report, which broke on August 21, 1968, in which it was revealed that secret visits had taken place between Cichy and King County Prosecutor Charles O. Carroll (1906-2003). The impropriety of their clandestine meetings was heightened by the fact that legal opinions issued by Carroll had allowed Cichy's organization to enjoy near-monopolistic control of the local pinball industry. After the story broke, Carroll refused to answer question from the media. Meanwhile, Washington Attorney General John J. O'Connell (1919-1998) requested that Governor Dan Evans (b. 1925) grant him the legal powers to conduct a thorough investigation of the matter. Evans initially declined this request, stating that it was too preliminary for such things. Later that year, it was announced that O'Connell had received the nomination to be the Democratic challenger against Evans's bid for re-election. The pinball scandal became a major campaign issue between the two men, with Evans claiming that O'Connell's investigation into Carroll was politically driven.

Evans would go on to win re-election and afterward would hand the Carroll and Cichy investigation over to Attorney General-elect Slade Gorton (1928-2020). However, on May 30, 1969, before a significant investigation could take place, Cichy was found drowned in shallow waters near his Lake Washington home. His death was ruled accidental, though there were many suspicions about the timing of the event, especially given that Cichy was noted to be an excellent swimmer. Gorton would later condemn Carroll's refusal to answer questions about the Cichy scandal, but concluded there was no evidence of extensive corruption.

Pinballs Go Mainstream

In 1970, former King County Sheriff Tim McCullough was indicted by a federal grand jury after disclosures were made about McCullough receiving improper financial contributions from Frank Colacurcio and Ben Cichy. That same year, Charles O. Carroll mounted a bid for re-election as King County Prosecutor. During the campaign, Carroll continued in his refusal to discuss his relationship with Cichy and would eventually lose the election to his challenger, Christopher T. Bayley.

Upon assuming his duties as the new prosecutor, Bayley launched an investigation into ongoing issues of corruption, resulting in the indictments of Carroll, as well as 18 other past and present city officials, including a former Seattle City Council president and a former Seattle police chief. The charges were "conspiracy of governmental entities" in connection with payoffs related to gambling, bribery, and prostitution. Carroll, along with most of the other defendants, was found not guilty of the charges, though his previous record of public service would be forever tarnished by the scandal.

These indictments would serve as the ending chapter for Seattle's so-called "pinball war" which, over the years, represented many different factions pitted against each other: the mayor vs. city hall; state government vs local municipalities; and unionized pinball operators vs. local crime syndicates. In the late 1960s it even became a politically divisive issue between the two candidates for Washington governor. The string of bombings that epitomized this era of Seattle history were never officially solved, and to this day remain a sordid chapter in the city's past.

As the last of these scandals unfolded, the first coin-operated video games started appearing on the scene and pinballs would finally shed their illicit reputation and gain mainstream acceptance as novelty games played for amusement and fun. And while Seattle once served as one of the nation's hotbeds for pinball-related vice, things have now gone full circle. The city currently boasts its own pinball museum, players of the game compete against one another at local competitions, and pinball machines – now seen with nostalgic fondness – are once again a regular feature at area taverns.